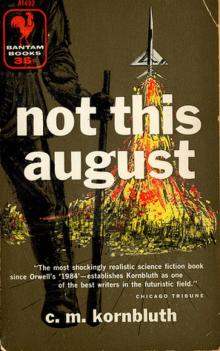

Not This August

C. M. Kornbluth

Not This August

C. M. Kornbluth

To my son David

“Not this August, nor this September; you have this year to do what you like. Not next August, nor next September; that is still too soon… But the year after that or the year after that they fight.”

—Ernest Hemingway

Notes on the Next War

BOOK 1

CHAPTER ONE

April 17, 1965, the blackest day in the history of the United States, started like any other day for Billy Justin. Thirty-seven years old, once a free-lance commercial artist, a pensioned veteran of Korea, he was now a dairy farmer, and had been during the three years of the war. It was that or be drafted to a road crew—with great luck, a factory bench.

He rose, therefore, at five-fifteen, shut off his alarm clock, and went, bleary-eyed, in bathrobe and slippers, to milk his eight cows. He hefted the milk cans to the platform for the pickup truck of the Eastern Milkshed Administration and briefly considered washing out the milking machine and pails as he ought to. He then gave a disgusted look at his barn, his house, his fields—the things that once were supposed to afford him a decent, dignified retirement and had become instead vampires of his leisure—and shambled back to bed.

At the more urbane hour of ten he really got up and had breakfast, including an illegal egg withheld from his quota. Over unspeakably synthetic coffee he consulted the electricity bulletin tacked to his kitchen wall and sourly muttered: “Goody.” Today was the day Chiunga County rural residents got four hours of juice—ten-thirty to two-thirty.

The most important item was recharging his car battery. He vaguely understood that it ruined batteries to just stand when they were run down. Still in bathrobe and slippers he went to his sagging garage, unbolted the corroded battery terminals, and clipped on the leads from the trickle charger that hung on the wall. Not that four hours of trickle would do a lot of good, he reflected, but maybe he could scrounge some tractor gas somewhere. Old man Croley down in the store at Norton was supposed to have an arrangement with the Liquid Fuels Administration tank-truck driver.

Ten-thirty struck while he was still in the garage; he saw the needle on the charger dial kick over hard and heard a buzz. So that was all right.

Quite a few lights were on in the house. The last allotment of juice had come in late afternoon and evening, which made considerably more sense than ten-thirty to two-thirty. Chiunga County, he decided after reflection, was getting the short end as usual.

The radio, ancient and slow to warm up, boomed at him suddenly: “… bring you all in your time of trial and striving, the Hour of Faith. Beloved sisters and brethren, let us pray. Almighty Father—”

Justin said without rancor, “Amen,” and turned the dial to the other CONELRAD station. Early in the war that used to be one of the biggest of the nuisances: only two broadcast frequencies allowed instead of the old American free-for-all which would have guided bombers or missiles. With only two frequencies you had, of course, only two programs, and frequently both of them stank. It was surprising how easily you forgot the early pique when Current Conservation went through and you rarely heard the programs.

He was pleased to find a newscast on the other channel.

“The Defense Department announced today that the fighting south of El Paso continues to rage. Soviet units have penetrated to within three hundred yards of the American defense perimeter. Canadian armored forces are hammering at the flanks of their salient in a determined attack involving hundreds of Acheson tanks and 280-millimeter self-propelled cannon. The morale of our troops continues high and individual acts of heroism are too numerous to describe here.

“Figures released today indicate that the enemy on the home front is being as severely and as justly dealt with as the foreign invader to whom he pledges allegiance. A terse announcement from Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary included this report: ‘Civilians executed for treason during the six-month period just ending—784.’ From this reporter to the FBI, a hearty ‘Well done!’

“The Attorney General’s office issued a grim and pointed warning today that the Harboring of Deserters Act means precisely what it says and will be enforced to the letter. The government will seek the death penalty against eighty-seven-year-old Mrs. Arthur Schwartz of Chicago, who allegedly gave money and food to her grandson, Private William O. Temple, as he was passing through Chicago after deserting under fire from the United States Army. Temple, of course, was apprehended in Windsor, Ontario, on March 17 and shot.

“Good news for candy lovers! The Nonessential Foodstuffs Agency reports that a new substitute chocolate has passed testing and will soon be available to B-card holders at all groceries. It’s just two points for a big, big, half-ounce bar! From this reporter to the hard-working boys and girls of the NFA, a hearty—”

Justin, a little nauseated, snapped the set off. It was time to walk up to his mailbox anyway. He hoped to hitch a ride on into Norton with the postwoman. The connecting rod of his well pump had broken and he was getting sick of hoisting up his water with a bucket. Old man Croley might have a rod or know somebody who’d make him one.

He dressed quickly and sloppily, and didn’t even think of shaving. “How are you fixed for blades?” wasn’t much of a joke by then. He puffed up the steep quarter mile to his box and leaned on it, scanning the winding blacktop to the north, from which she would come. He understood that a new girl had been carrying the mail for ten days or so and wondered what had happened to Mrs. Elkins—fat, friendly, unkempt Mrs. Elkins, who couldn’t add and whose mailbox notes in connection with postage due and stamps and money orders purchased were marvels of illegibility and confusion. He hadn’t seen the new girl yet, nor had there been any occasion for notes between them.

Deep in the cloudless blue sky to the north there was a sudden streak of white scribbled across heaven—condensation trail of a stratosphere guided missile. The wild jogs and jolts meant it was set for evasive action. Not very interested, he decided that it must be a Soviet job trying just once more for the optical and instrument shops of Corning, or possibly the fair-sized air force base at Elmira. Launched, no doubt, from a Russian or Chinese carrier somewhere in the Atlantic. But as he watched, Continental Air Defense came through again. It almost always did. Half a dozen thinner streaks of white soared vertically from nowhere, bracketed the bogey, and then there was a golden glint of light up there that meant mission accomplished. Those CAD girls were good, he appreciatively thought. Too bad about Chicago and Pittsburgh, but they were green then.

He sighed with boredom and shaded his eyes to look down the blacktop again. What he saw made him blink incredulously. A kiddie-car going faster than a kiddie-car should—or a magnified roller skate—but with two flailing pistons—

The preposterous vehicle closed up to him and creaked to a stop, and was suddenly no longer preposterous. It was a neatly made three-wheel wagon steered by a tiller bar on the front wheel. The power was supplied by a man in khaki who alternately pushed two levers connected to a crankshaft, which was also the rear axle of the cart. The man had no legs below his thighs.

He said cheerfully to Justin: “Need a farmhand, mister?”

Justin, manners completely forgotten, could only stare.

The man said: “I get around in this thing all right and it gives me shoulders like a bull. Be surprised what I can do. String fence, run a tractor if you’re lucky, ride a horse if you ain’t, milk, cut wood, housework—and besides, who else can you get, mister?”

He took out a hunk of dense, homemade bread and began to chew on it.

Justin said slowly: “I know what you mean, and I’d be very happy to hire you if I could, but I can’t. I’m just snake-hipping through the Farm-or-Fight Law with eight cow

s. I haven’t got pasture for more and I can’t buy grain, of course. There just isn’t work for another pair of hands or food for another mouth.”

“I see,” the man said agreeably. “There anybody around here who might take me on?”

“Try the Shiptons,” Justin said. “Down this road, third house on the left. It used to be white with green shutters. About two miles. They’re always moaning about they need help and can’t get it.”

“Thanks a lot, mister. I’ll call their bluff. Would you mind giving me a push off? This thing starts hard for all it runs good once it’s going.”

“Wait a minute,” Justin said almost angrily. “Do you have to do this? I mean, I tremendously admire your spirit, but Goddamn it, the country’s supposed to see that you fellows don’t have to break your backs on a farm!”

“Spirit hell,” the man grinned. “No offense, but you farmers just don’t know.”

“Isn’t your pension adequate? My God, it should be. For that.”

“It’s adequate,” the man said. “Three hundred a month—more’n I ever made in my life. But I got good and sick of the trouble collecting it. Skipped months, get somebody else’s check, get the check but they forgot to sign it. And when you get the right check with the right amount and signed right, you got four-five days’ wait at the bank standing in line. I figured it out and wrote ’em they could cut me to a hundred so long as they paid it in silver dollars. Got back a letter saying my bid for twenty-five gross of chrome-steel forgings was satisfactory and a contract letter would be forthcoming. I just figured things are pretty bad, they might get worse, and I want to be on a farm when they do, if they do. No offense, as I say, but you people don’t know how good you have it. No cholera up here for instance, is there?”

“Cholera? Good God, no!”

“There—you see? Mind pushing me off now, mister? It’s hot just sitting here.”

Justin pushed him off. He went twinkling down the road, left-hand-right-hand-left-hand-right—

Cholera?

He hadn’t even asked the man where. New York? Boston? But he got the Sunday Times every week—

The postwoman drove up in a battered ’54 Buick. She was young and pretty, and she was obviously scared stiff to find a strange unshaven man waiting for her at a stop.

“I’m Billy Justin,” he hastily explained through the window lowered a crack. “One of your best customers, even if I did forget to shave. Anything for me today?”

She poked his copy of the Times through the crack, smiled nervously, and shifted preparatory to starting.

“Please,” he said, “I was wondering if you’d do me a considerable favor. Drive me in to Norton?”

“I was told not to,” she said. “Deserters, shirkers—you never know.”

“Ma’am,” he said, “I’m an honest dairyman, redeemed by the Farm-or-Fight Law from a life of lucrative shame as a commercial artist. All I have to offer is gratitude and my sincere assurance that I wouldn’t bother you if I could possibly make it there and back on foot in time for the milking.”

“Commercial artist?” she asked. “Well, I suppose it’s all right.” She smiled and opened the door.

It was four miles to Norton, with a stop at every farmhouse. It took an hour. He found out that her name was Betsy Cardew. She was twenty. She had been studying physics at Cornell, which exempted her from service except for R.W.O.T.C. courses.

“Why not admit it?” She shrugged. “I flunked out. It was nonsense my tackling physics in the first place, but my father insisted. Well, he found out he couldn’t buy brains for me, so here I am.”

She seemed to regard “here”—in the driver’s seat of a rural free delivery car, one of the cushiest jobs going—as a degrading, uncomfortable place.

He snapped his fingers. “Cardew,” he said. “T. C.?”

“That’s my pop.”

And that explained why Betsy wasn’t in the WAC or the CAD or a labor battalion sewing shirts for soldiers. T. C. Cardew lived in a colonial mansion on a hill, and he was a National Committeeman. He shopped in Scranton or New York but he owned the ground on which almost every store in Chiunga County stood.

“Betsy,” he said tentatively, “we haven’t known each other very long, but I have come to regard you with reverent affection. I feel toward you as a brother. Don’t you think it would be nice if Mr. T. C. Cardew adopted me to make it legal?”

She laughed sharply. “It’s nice to hear a joke again,” she said. “But frankly you wouldn’t like it. To be blunt, Mr. T. C. Cardew is a skunk. I had a nice mother once, but he divorced her.”

He was considerably embarrassed. After a pause he asked: “You been in any of the big cities lately? New York, Boston?”

“Boston last month. My plane from Ithaca got forced into the northbound traffic pattern and the pilot didn’t dare turn. We would’ve gone down on the CAD screen as a bogey, and wham. The ladies don’t ask questions first any more. Not since Chicago and Pittsburgh.”

“How was Boston?”

“I just saw the airport. The usual thing—beggars, wounded, garbage in the streets. No flies—too early in the year.”

“I have a feeling that we in the country don’t know what’s going on outside our own little milk routes. I also have a feeling that the folks in Boston don’t know about the folks in New York and vice versa.”

“Mr. Justin, your feeling is well grounded,” she said emphatically. “The big cities are hellholes because conditions have become absolutely unbearable and still people have to bear them. Did you know New York’s under martial law?”

“No!”

“Yes. The 104th Division and the 33rd Armored Division are in town. They’re needed in El Paso, but they were yanked North to keep New York from going through with a secession election.”

He almost said something stupid (“I didn’t read about it in the Times“) but caught himself. She went on: “Of course, I shouldn’t be telling you state secrets, but I’ve noticed at home that a state secret is something known to everybody who makes more than fifty thousand a year and to nobody who makes less. Don’t you feel rich now, Mr. Justin?”

“Filthy rich. Don’t worry, by the way. I won’t pass anything on to anybody.”

“Bless you, I know that! Your mail’s read, your phone’s monitored, and your neighbors are probably itching to collect a bounty on you for turning you in as a D-or-S.” A “D-or-S” was a “disaffected or seditious person”—not quite a criminal and certainly not a full-fledged citizen. He usually found himself making camouflage nets behind barbed wire in Nevada, never fully realizing what had hit him.

“You’re a little rough on my neighbors. Nobody gets turned in around here for shooting off his mouth. It’s still a small corner of America.”

Insanely dangerous to be talking like that to a stranger—insanely dangerous and wildly exhilarating. Sometimes he hiked over to the truck farm of his friends the Bradens, also city exiles, and they had sessions into the small hours that cleared their minds of gripes intolerably accumulated like pus in a boil. Amy Braden’s powerful home brew helped…

Rumble-rumble, they rolled over the Lehigh’s tracks at the Norton grade crossing; Croley’s store was dead ahead at the end of the short main street. Norton, New York, had a population of about sixty old people and no young ones. Since a few brief years of glory a century and a half ago as a major riverboat town on the Susquehanna it had been running down. But somehow Croley made a store there pay.

She parked neatly and handed him a big sheaf of mail. “Give these to the Great Stone Face,” she said. “I don’t like to look at him.”

“Thanks for the ride,” he said. “And the talk.”

She flashed a smile. “We must do it more often,” and drove away.

Immediately, thinking of his return trip, he canvassed the cars and wagons lined up before Croley’s. When he recognized Gus Feinblatt’s stake wagon drawn by Tony and Phony, the two big geldings, he knew he had it made. Gus was that fa

ntastic rarity, a Jewish farmer, and he lived up the road from Justin.

The store was crowded down to the tip of its ell. Everybody in Norton was there, standing packed in utter silence. Croley’s grim face swiveled toward him as he entered; then the storekeeper nodded at a freezer compartment where he could sit.

Justin wanted to yell: “What is this, a gag?”

Then the radio, high on a shelf, spoke. As it spoke, Justin realized that it had been saying the same thing for possibly half an hour, over and over again, but that people stayed and listened to it over and over again, numbly waiting for somebody to cry “Hoax” or “Get away from that mike you dirty Red” or anything but what it would say.

The radio said: “Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States.” Then the inimitable voice, but weary, deathly weary. “My fellow Americans. Our armed forces have met with terrible defeat on land and at sea. I have just been advised by General Fraley that he has unconditionally surrendered the Army of the Southwest to Generals Novikov and Feng. General Fraley said the only choice before him was surrender or the annihilation of his troops to the last man by overwhelmingly superior forces. History must judge the wisdom of his choice; here and now I can only say that his capitulation removes the last barrier to the northward advance of the armies of the Soviet Union and the Chinese People’s Republic.

“My fellow citizens, I must now tell you that for three months the United States has not possessed a fleet in being. It was destroyed in a great air-sea battle off the Azores, a battle whose results it was thought wisest to conceal temporarily.

“We are disarmed. We are defeated.

“I have by now formally communicated the capitulation of the United States of America to the U.S.S.R. and the C.P.R. to our embassy in Switzerland, where it will be handed to the Russian and Chinese embassies.

“As Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the United States I now order all officers and enlisted men and women to cease fire. Maintain discipline, hold your ranks, but offer no opposition to the advance of the invading armies, for resistance would be a futile waste of lives—and an offense for which the invading armies might retaliate tenfold. You will soon be returned to your homes and families in an orderly demobilization. Until then maintain discipline. You were a great fighting force, but you were outnumbered.