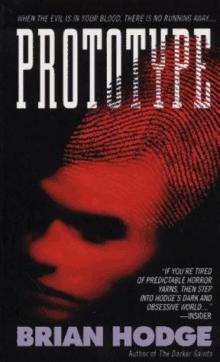

Prototype

Brian Hodge

Table of Contents

PROTOTYPE

Foreword to the Second Edition, by John Shirley

PART ONE/RUST

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

PART TWO/CORROSION

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

PART FOUR/DUST OF A FADED DECADE

Thirty-Seven

About The Author

PROTOTYPE

by Brian Hodge

PROTOTYPE copyright © 2010 by Brian Hodge. Originally published 1996 by Bantam Doubleday Dell. Second edition published 2007 by Delirium Books. Macabre Ink digital edition published 2010.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Except for review or discussion purposes, no part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electrical or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the author.

This book is a work of fiction. Characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from imagination and are not to be construed as real, or are otherwise used fictionally. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

— William Shakespeare

If you can't be a good example, then you'll

just have to be a horrible warning.

— Catherine Aird

For Doli —

for too many reasons

to list on one page;

but a lot of them are

in the ones that follow.

Foreword to the Second Edition, by John Shirley

This is a foreword; it is supposed to tell you things about a book before you read it. But no author wants someone else to spoil his story or tell the reader: “This is what it is all about, man, this is the true meaning that I will now reveal unto you…”

So I’m not going to do that in my foreword.

Of course you can always write about how the book came about … but I have no idea how it came about.

A lot of forewords are about the foreworder’s personal relationship to the author, how you go back years together and have shared many deep thoughts or at least a lot of beers.

I know Hodge, but not well. At least one of the conventions we were both at I’ve even tried to block out of my memory (or possibly my brain damage blocked it out) and my agent, who knows Hodge better than I do, had to remind me about it. Anyway, I’ve never bonded with him in that collegial way that writers sometimes do. I also never bonded with him, in the bad old days, by waking up in the same pool of puke in a back room somewhere. (At least, I don’t think that was Hodge.)

I know Hodge only from his work and, frankly, I haven’t read a great deal of it. Don’t take that wrong. The fact that I’ve read any of it at all is a real compliment. I don’t read much fiction at all and even less that can be considered “genre” fiction. This is not unusual, by the way. I don’t think my friend Tim Powers has read any genre fiction published in the last thirty or so years, unless it’s by Jim Blaylock. (Well, he read my Demons, but I’m not sure he considered that “genre”.) I understand Clive Barker will not read fiction of any kind when he is himself writing fiction.

But I have read some of Hodge’s work and I know he’s a damned good writer. He’s also a damned dark writer. He illuminates our own personal darknesses by showing us the darker dark. And this book, Prototype, is, as far as I know, the darkest thing he’s ever written. It is as if, after he wrote this one, he saw some light himself and never needed to go back down to this depth.

Clay Palmer, the strange mutant character in Prototype, is the ultimate misfit, a freak, a man in whom the worst human aggression is heightened past all endurance, multiplied to the point of unquenchable, consuming rage that must result in the destruction of others and of himself. Wait — was Hodge writing about me, when I was, like, 25? No, he didn’t know me then. But he’s writing about all youthful male alienation, when it’s alienation keyed to the point of igniting rage. And in this case, igniting something else…

But even though he is what he is, Palmer still has a choice. He wants to “rise above” what he is.

It always struck me that in, say, the movie Blade Runner, as in the Phil Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? underlying that film, the rebellious androids were really stand-ins for humanity, for everyone angry, secretly or out front, about mortality; angry that they are brought into the world to live and learn and then must die before having a real chance to live, a chance to really learn. And in Prototype Palmer seems to me to represent everyone who finds themselves hating what they are — at least at first — until they learn to understand their true nature. And that’s most of us, at least at some point — most of us, if only as insecure adolescents, but often later in our lives, too — look at ourselves with profound dissatisfaction. Why was I this and not that? I was intended to be an Olympic skater! Or: I was supposed to be a scientist! Or: Why’d I waste my life training to be an Olympic skater, when really I wanted to be a scientist? I was supposed to be smart or slim or witty or talented or a much kinder person people would like and cherish and…

But what I am is … what I am. And we go through a process of finding out what we are. We model different versions, in high school and college — often in the process of trying this “major” and then shifting to that one, or going from studying philosophy to vocational school. We take adult classes to be more…something else. But eventually we work out who we are.

Most good science-fiction, you see, is about something other than what it immediately seems to be about. The best science-fiction or horror is metaphor — it’s a great story, as this book is, but it also resonates on some deeper level for us. Prototype resonates with questions of identity and what it means to be human.

People tend to sleepwalk through their lives. If they become aware of it, they either try to go deeper asleep — maybe by drinking, taking drugs, spending half their lives in role-playing games online — or they struggle to wake up. A motivator for waking up is wanting to change. To become master of oneself. To do that, you have to be able to make choices. Sleepwalking, knee-jerk people can’t make choices. Somewhere in Prototype is an understanding of just those issues — to change, you have to wake up enough to see yourself as you really are. Then — maybe. You have to accept who you are … but there’s always another possibility. The chance for evolution…

At one point, Clay and his kind are called “outsiders adrift in societies for which they have more contempt than love.” Some writers are like that or at least writers like me — maybe Hodge too. Others are more like the Impressionist artist, Willard Metcalf, whose “The White Veil” Palmer describes as, “Fuzzy, soft focus … diffused. Even though that’s a winter scene, it’s still warm.”

Writers who write dark fiction are more like Clay’s artist friend, Graham, whose work reflects a harsher — and more relevant — truth in which you can find a perverse beauty.

It is not that writers of dark fantasy and sf cannot see beauty or have no hope or feel such things are irrelevant. It’s that we know that making that choice to rise above, to be aware and awake, is not easy. Once the choice is made, you have to continue to choose and that is more difficult still. Writers like Hodge know that and they aren’t going to lie to you and make it soft and fuzzy. Sometimes we are even going to be, well, a little extreme.

Just a little, though, because people like Hodge and myself aren’t nihilists. We might be accused of that — punk rock is often labeled nihilistic and I’ve been known to be a punk rocker — but we know better. That fictional artist, Graham, is a nihilist and he creates a work of art that is as extreme as it gets: The Dream of Kevorkian. I’ll let you discover just where Hodge sees nihilism taking an artist.

There’s nothing soft or fuzzy about Prototype. Oh it has its touching moments — the lesbian relationship between Adrienne and Sarah is as real and nuanced and sophisticated as any I’ve read. Pretty good coming from a male. Not something I’d try — and he pulled it off.

When Prototype was first published it had the word “horror” on its spine. I imagine you’d still call it horror now too but keep in mind as you read this book that if this had been a generic horror novel, Hodge would have told his story more or less like this: Clay is a monster. Maybe it is not his fault he’s a monster, but he is one, so he is, therefore, evil. His doctor, Adrienne, wants to help him not be a monster. In a conventional horror novel they might even fall in love because the power of love might save the day. (Besides women, in that sort of book are only allowed to be good or bad themselves. And she’s a scientist, and there’s only good or bad science.) But, one way or another there would be a confrontation between “good” and “evil.” Good will more or less win, one way or another, because that’s how those stories are supposed to work.

Note that Hodge does just about everything a writer can do to avoid that formula and he does it in many different ways. But few of them are simple ways. A simple way would have been pull a reverse — good is evil, evil is good. He plays with that concept with a character, Patrick Valentine, who quotes Nietzsche a lot and seems to think that the “monsters” here represent the “atavism of a more ancient world” and that monstrosity is inevitable.

In the end, well, you’ll have to decide about the ending of this book yourself, but I think you may find that you will feel every character has made a key mistake, made at least one wrong choice at some turn. Long before reaching the conclusion you’ll also understand that the world itself and society, in Prototype, is the end sum of humanity’s many mistakes. (There’s not a lot about the nonfictional world that doesn’t support that idea.)

In fiction, you write resolutions. There is an end. At most, like here, there is an epilogue. As a reader, you close the cover and there is no more. The End. Choices, mistakes, consequences — all over. Whatever impression that writer is going to make has been made.

And Brian Hodge makes a lasting impression with Prototype.

Life’s not like a novel. We don’t write our lives and resolve our dilemmas so easily. But Prototype will at least lead you to consider the higher questions … questions that have a secret relevance to your own life.

John Shirley

February 15, 2006

PART ONE/RUST

It pointed to the generation of all these creeds. They were assertions, not arguments; so they required a prophet to set them forth… Their birth set them in crowded places. An unintelligible passionate yearning drove them out into the desert.

— T.E. Lawrence

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

One

After the calm, Adrienne looked in on her patient, up from Emergency and now in his room. He was at such peace, and she marveled: The difference between the countenance of a devil and that of an angel is sometimes nothing more than sleep.

It was an archaic association, the kind she would always have to keep to herself. How many fellow psychologists, colleagues and mentors alike, would frown upon such medieval terminology? Angels, devils; good, evil; black, white … no such things. The modern age had sounded the death knell for such absolutes.

There existed but chaos and order, illness and health.

But if the metaphor fits … apply it.

The patient, peaceful now, lay beneath the precautionary restraints across his bed. He was, so far, without name, without history. He was nothing but symptoms and wounds. An IV line snaked into one arm to boost fluid levels; he was suffering from mild dehydration. He had been brought in without ID, and the police had been unable to take fingerprints even after he'd been sedated into sleep: Both hands were heavily stitched, splinted, and bandaged.

Adrienne held little hope for a lucid talk with him tomorrow. Only someone suffering from extreme personality disturbances would not only break his own hands on another's face, but continue to pummel away until jagged fragments of his own metacarpals protruded from his hands in compound fractures.

The patrol officers who had brought him in earlier tonight, in restraints, told her that he had been picked up on the east side of Tempe, at a shopping strip. That he had spent a good deal of time in the Arizona desert seemed a reasonable deduction. There had been sand and dust inside his boots, with his jacket and jeans heavily coated as well. According to the police, witnesses to the altercation that had landed him here said that three skateboard thugs had tried to relieve him of his wallet as he was leaving a Tex-Mex stand. All three of them, ironically, had been brought in as even more deserving emergency cases.

Comical enough in its beginnings, Adrienne supposed: The kid who'd snatched the wallet from their John Doe's hand had been knocked from his skateboard by a well-aimed sack of tacos to the head. After which the victim had become the aggressor. He had snatched up the upended skateboard and used its flat, wide top to shatter its owner's nose.

The melee was joined at once by the other two, valiantly altruistic musketeers, the both of them — in their own eyes, at least. Adrienne well knew that boys in their late teens listened far more readily to testosterone than to common sense.

And they had paid dearly. Between the three of them, their tally of injuries was headed by a broken jaw, two broken noses, nine missing teeth, one shattered elbow, two ruptured testicles, a skull fracture, thirteen broken ribs. One would be urinating blood for days. Then there were the punctures and lacerations caused by the bones protruding from John Doe's hands.

Adrienne, as a staff psychologist, had not treated them, had scarcely even seen them. Her understanding of the hapless trio's fate was mainly appraisal from colleagues working the night shift. While grievous injuries they were, Adrienne found it difficult to sympathize. Three-on-one was such an act of vicious cowardice. She despised the pack mentality — an evolutionary carry-over, perhaps, still buried in the primal brain, but a behavioral anachronism. Like a burst appendix, it could cause only misery. Surely human beings were better than that, somewhere within, weren't they?

Apparently their John Doe, bruised and battered but the last one on his feet, had attempted to lurch away from the scene, and even then had needed two police officers to subdue him. His bone-razor hands were secured behind his back and in he came, 9:22 P.M. this September midweek night. He was an immediate code blue, all available able-bodied personnel converging on the ER entrance to make sure he hurt no one else or did no more damage to himself. His hands may have been bound, but he had feet. And teeth. And a seemingly bottomless reservoir of ferocious energy — adrenaline, most likely. A later blood test checked negative for presence of drugs.

Drugs had, in the end, been their only recourse to stop him. He nearly had to be submerged in Thorazine before it took effect.

Adrienne had witnessed, had felt an unexplained sorrow after the final plunge of the

needle into exposed arm, a drama played out by nearly a dozen participants — oh, here was a pack in action. Watching John Doe's struggles dwindle to twitches, and the fury fade from his eyes as they shut, yet even then still seemed to hate, she had thought of animals she'd seen on documentaries beyond number: fine and noble predators such as lions and tigers and panthers, enraged at the sting of the dart in their hip, and given to spectacular acrobatics even as consciousness ebbed. At the end, wobbly and confused, they invariably seemed like nothing so much as cubs, clumsy and mystified. And then they fell.

John Doe … where did you come from, and where were you going? And what demons followed you within?

Demons in, of course, a wholly figurative sense.

She kept that to herself too.

*

Adrienne had but a half-hour remaining on her shift, and it went peacefully enough. Midnight came and she knocked off duty but had little desire to leave the hospital. Ensconced in her office, she rang home and got the machine; left a message that she had a patient for whom she wanted to be on-site whenever he came around, and would probably be home later in the morning.

Silence, then. Was any place so quiet as a hospital office after midnight? Off came her shoes and she wiggled her feet for a moment, felt full circulation restore; then she cranked the Levolor blinds into a barrier and raised her slacks' legs to peel away her knee-highs.

She dropped to sit on the couch. That was the great thing about her chosen career — always a place to sleep. Adrienne shut her eyes and did some slow, deep breathing, let the day and tonight's shift ease out of her one lungful at a time. Directly across the office, centered between packed bookshelves, she kept hung a large square print of a landscape from early American impressionism, Willard Metcalf's The White Veil. She regarded it as mildly hypnotic, so serene she could nearly hear the whisper of its falling snow. It was easy to lose herself in the painting every time, wander down its blanketed hillsides to the valley below, and even the bleakness of its bare trees seemed softened beneath a milky gray sky. Such a glaring contrast to the stark desert landscape that surrounded her waking world, and she supposed that was a large part of its appeal. Perhaps she was being quietly obstinate.