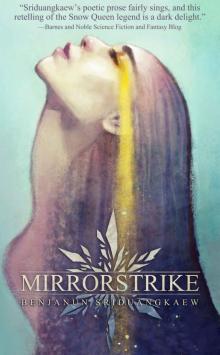

Mirrorstrike

Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Mirrorstrike

Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Copyright © 2019 by Benjanun Sriduangkaew

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Cover art by Anna Dittman.

Jacket design by Mikio Murikami.

ISBN TPB 978-1-937009-73-1

Also available as a DRM-free eBook.

Apex Publications, PO Box 24323, Lexington, KY 40524

Visit us at www.apexbookcompany.com.

Contents

Two to Bind

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

About the Author

Also by Benjanun Sriduangkaew

Two to Bind

In the house of the Winter Queen, even time itself slows.

Above Nuawa, the prisoner swings in shallow parabolas, a human pendulum suspended by iron and harness. She has never thought a body could be reduced so small. Ytoba is little more than a torso, ice clinging to the stumps where eir limbs used to be. By right ey should have long succumbed. She was the one to hack those limbs off and she was not delicate about the task—the hemorrhage alone should have been fatal. Somehow ey persists.

At the moment, Ytoba is wearing the face of Nuawa's mother, Indrahi.

As Nuawa understands it, the act of shifting shapes costs em: like any other physical exertion it places demands on the flesh. Ey hasn't been fed much recently, only water and the thinnest gruel, the occasional rice boiled to soft mush. She is sure—she has personally been forcing every watery spoonful down eir throat. It should have left em too malnourished to think, let alone alter eir shape, to her mother's or anyone else's.

"Are you," ey whispers with her mother's voice, "going to kill me again?"

"I'm aware of who and what you are, and my mother's ghost you are not." She gazes at the frieze behind em, gray ice and blue glass on the wall, water crystals arranged into the shape of hyacinths, Her Majesty's flower. Here even the prison cells are beautiful, the same way moraines are. "There's no real point in keeping you, save for the general's sentiment. She may show you mercy. I have no interest."

Ey smiles. Her mother's mouth. "Afraid I might betray you by revealing what you were up to? Exposing you to the prince. Though I'm sure you'll never let me have audience with her."

Nuawa shows em her wrist, where the hyacinth glints like a small faceted knife. "I've been sworn in, and General Lussadh has even less interest in speaking to you than I do." The general being half a continent away.

"There are laws and forces you're dealing with that you fail to understand. One to wake. Two to bind. By and by you shall lose your will, become the queen's creature in truth as well as pretense. Your mother's plot and her legacy wearing thin, then wearing out, then simply wiped away. I am sure your mother will be proud." Ey gazes at her unblinking. "And you're dying too, aren't you?"

"Am I? Every minute we're dying. Some faster than others."

"I'm an expert. I can smell poison—some parasite. Very creative. It's not contagious though, not until it spawns, and by that point you'd be in no state to spread it anywhere. If you mean to assassinate Prince Lussadh during intimacy, this is an exceptionally poor method."

Impotent taunts, until the end. "This is all you have to say?"

"What did you reckon? That I would give you the queen's secrets? After you've done so much for me." The smile widens and, at last, it no longer resembles her mother's: toothed, grotesquely wide. Further than any human mouth should be able to stretch. "Anything I know will have to go with me to the next earth."

"Well," she says, drawing her gun, "that is that, then."

The ice shudders to gunfire acoustics, a few icicles falling off, tinkling a pretty, abortive melody. The assassin sags in the harness. In death ey does not revert to eir true face, true shape. In death, ey looks almost like Indrahi when Nuawa shot her.

But she is no child, and can separate fact from fantasy. She loosens the harness, turns the torso around, checking for a pulse one last time. There is none. For good measure, she slits the shapeshifter's throat. Even in this chill, the arterial system still has power; the blood leaves em in a burst, drenching her sleeves. The rest puddles under em, soaking the harness and the frost tiles. More black than red, under this light.

"This is for you, Mother," she says, but there is no answer. Only the cold, the dark, and the weight of history like a noose around her throat.

One

Lussadh hunts. The night is deep and the frosted roofs gleaming with ice, but she is used to both. She moves with precision, a foot in a crack between slates, another on a ledge that would bear her weight but only just. It is quiet. Cities under siege always are: she knows from experience, having been on both the defending and invading ends. For those defending, familiar streets and intersections distort; all laws and rules shift to accommodate the factors of combat always impending.

She glances briefly behind her shoulder, in the direction where her army camps, awaiting her next command. From this distance they are not visible, obscured by the high, high walls. Citizens of Kemiraj may even pretend they are at peace and that their magistrate has not revolted against the Winter Queen. She turns her gaze back to her destination, inhaling the clean, crystalline air. When was it that she's become at home wherever snow is, has taken the queen's element as her own? It must have been gradual, but it has happened so seamlessly that she no longer remembers a time when she felt otherwise and called herself a child of the desert.

Not that there's much desert left, now.

A step, then another. She climbs until there is no further handhold and no further roof. A gap yawns between the platform she occupies and the top of the wall that protects the magistrate's mansion. She judges the distance, draws back, and leaps.

She lands easily, with minimal noise. A matter of training—from her youth she was tutored by court assassins—and a matter of agility granted by the queen's mirror. The slight, subtle strengths that together come to something more. Lussadh will be fifty soon and hardly feels the fact. Her body may not be the tireless engine it was at sixteen or twenty-five, but it remains formidable, lightly touched by age. Joints and muscles well-oiled as ever. A day will come when all these fail, but through her queen's blessing, that is yet held at bay.

Through the garden she moves, concealed by shadow and a veil of aversion made by one of her officers. Not the most potent thaumaturgy, but it deflects attention, makes her peripheral to the naked sight. Major Guryin is practiced at such things, the minor alterations, the tricks of perception. It would not hold against direct scrutiny. Still she has little enough to worry about. The city's military falls into two categories: loyal to winter and therefore dead—Magistrate Sareha executed them with the suddenness of garrotes in the dark—or loyal to Sareha and therefore vanishingly few. Of that handful, most have been decimated by Lussadh's army. Sareha would not be able to muster more than ten soldiers to defend her estate.

The grass is nearly as tall as she is, the trees black and dense.

She feels more than hears the velocity of it, the metal cutting through the air. Time enough to turn so the shard buries itself in her right shoulder instead of her throat. She drops to her knees, half-hidden in the shrubs, her back against the base of a marble plinth. Smaller target this way. Her breathing

judders.

Lussadh doesn't try to extract the flechette. It has gone in too deep, piercing armor as though it is paper instead of reinforced mesh, and the tip is not tidy. Someone knew she would be here, and that she'd wear armor witched to blunt the brute force of a bullet. Needle guns are uncommon, an occidental invention and a specialist's choice. Short range. She searches overhead, in the rough direction the shot originated. Nothing. Like her, the sniper must have upon them a charm that averts sight. But now she knows what to look for and, as tempting a target as she is, the next shot must come.

A glint, handgrip or barrel. Even painted for nocturnal use, a needle gun is mostly metal.

She switches hands, takes aim, fires. Her tutors impressed upon her the importance of being able to shoot with either hand.

The would-be assassin falls like an overripe fruit. Lussadh touches her calling-glass and says, "Guryin. Fly your scout low."

Instantly the hawk-shadow that has been trailing her plunges into the canopies, a thing of etheric wings like knives. Entirely silent. Another body drops. The hawk-shadow emerges again and propels forward, the momentum of a bullet.

"You're clear, General." The major's pause is slight but admonitive. "Are you going ahead?"

"It seems wasteful not to."

A truncated sigh. "The magistrate is on the second floor. Up the stairs, turn left, end of corridor. There's no other security that I can detect, thaumaturgic or otherwise—this time I've made sure. My apologies for that one stray."

Guryin does not inquire as to the state of her wound, trusting that Lussadh can make her own judgment. Which she can, though perhaps the major is not wrong that going forward here is unwise. She stands: the pain has receded a little, the way sensation numbs in extreme cold, and the bleeding has slowed to a trickle. Left untreated it can still kill, but for now she can push on.

True to Guryin's word, no other surprise awaits her on the manor ground or inside the building itself. Fortunate that the magistrate has retreated to her mansion rather than occupy the al-Kattan palace. No doubt both because the manor is easier to defend—smaller area, fewer points of exit and entry—but also because the palace would not abide Magistrate Sareha's treachery. The living architecture, after all this time, still answers to al-Kattan blood first and foremost. The moment news of the uprising reached Lussadh, she'd willed its gates and doors to clench shut. But by then Sareha had fled the palace, holing herself up in her own manor.

The house is well-lit. Lussadh passes long dining tables that have been set for ten, for dozens. Beautiful enameled plates rimmed with bird-faced dancers, brass spoons and samovars, and thread of gold in the tablecloth. She goes up the stairs. It is a short corridor, and the door in question is unlocked.

Magistrate Sareha sits by the window. She is stooped, a woman who was not young when Lussadh selected her from a clerical post in Shuriam; she closes in on eighty now. Without looking at Lussadh, she says, "You should be in too much pain to move, and bleeding buckets besides. It's true what they say, that you've become a demon after you submitted to the queen."

Suspension or postponement of time is not the same as immortality, but Lussadh does not quibble the difference. There is use in being thought of as preternatural. "I've come to offer you mercy."

The old woman does not laugh. Instead she stands and draws a machete. The blade is curved inward, graceful. "I'm old and weak. You're injured, though unnatural. Fight me. It will not be fair, but it will give me dignity."

"I fear I must decline." The appeal upon her chivalry, which Lussadh supposes she is famous for. She does understand her magistrate's pride: the last stand, the final gesture. But she has no intention of indulging it, and her wounded shoulder is throbbing like a heart about to go into cardiac arrest. "These are your choices: Surrender and answer my questions, and I'll give you death without the kiln. Refuse and I will disable you, and give your soul to the queen's service, as is right for high treason."

Now Sareha does laugh. "As I understand, the ghosts aren't really sentient. Mindless shadows are all they are, and all I will be in that state. Mercy you call it, when dignified death should be everyone's by right. Even the most bloodthirsty tyrants of Kemiraj left our souls alone. But either way, I won't be around to care."

"I swore you in and assigned you this post, to govern Kemiraj when my aide and I are away. I lifted you up from the bones and mud of Shuriam. Why this?"

"I've been dying for years—an illness of the blood, you see, and age. There's nothing left for me to lose and I have hated your queen for decades. I've hated the al-Kattan for longer still, for who was it that reduced my home Shuriam to mud and our beautiful fastnesses to ruin?" The old woman hefts the machete, turning it this way and that, the blade catching light. "There comes a point when you must make a decision, and I wanted to show you that even a dying old woman may upset your order, even just for a month or two, and massacre more than two hundred pledged to your army."

The tally is closer to three hundred, most of them infantry and recruits native to Kemiraj. It was swift and comprehensive. Lussadh has to give her that. "I did not invade Shuriam because I wished to," she says. It sounds weak even to her ears.

"But because your grandaunt King Ihsayn ordered it? What a luxury it is, to undertake conquest even though you do not wish. If only we could have turned the conquering horde away by virtue of wishing." Sareha's voice lilts high, mocking. "It wasn't atonement, Prince Lussadh, when you butchered your own family—that was for your own ambition. It wasn't atonement when you so graciously elevated me—that was for your own guilt, and because you'd executed nearly every Kemiraj official who served Ihsayn. Someone needed to work for you, and I did well, didn't I? How I proved myself and acted the grateful servant who owed you everything."

The old woman lunges. She is right that the days of her strength are ancient history. Lussadh stays out of the magistrate's reach without effort. She lets Sareha swing away, wild and weak, striking at nothing. It is graceless. She takes aim; she shoots to kill. The bullet goes through skull without resistance, so brittle it is, so aged the bone. The body is so light it barely makes sound on the carpet.

Sareha was seventy-five, and there is dignity in dying that old with a weapon in hand, Lussadh thinks. It is what she tells her soldiers in times of low morale.

She holsters her gun and goes to the window where the magistrate was sitting. On the sill there is a handful of ash, gray and fine. Burnt paper, she judges. She gathers the remains into a little cedarwood box lying open close by: a thaumaturge might be able to reconstitute the ash.

Tentatively she parts the curtain. The room is so well lit that all she sees is her own reflection, as Sareha must have before she drew down the drapes. When she was a child, Lussadh thought murder would alter someone so fundamentally that even the appearance must change to match: a shadow that runs a little longer, a countenance darkened by bloody event. By ten or so, she learned that such deeds change very little, inside or outside.

A glint catches her eye, a noise of ice crackling. It is distinct: she is intimately familiar with the harmonics of cold. Just outside the window, a scrim of frost is falling apart. There is shape to it, thin and tall and humanoid. But that quickly dissolves, and soon nothing remains on the pane.

* * *

In the safety of her camp, Lussadh lies back in a divan, groggy from anesthetics. Her wound has been dressed, the flechette removed, and the retaking of Kemiraj is apace. She cannot yet rest and there will be a great deal of labor in days to come. Executing the old woman was more a formality than anything, mostly for Lussadh's sense of closure. The thing that might get her killed, one day, a point that Major Guryin has taken pains to drive home.

A knock on her door. Her aide Ulamat. "My lord," he says, wincing at the sight of her injury. "This was very ill-advised."

"Had we stormed her manor, she'd have committed suicide long before we got there. I wanted to speak to her." She shrugs her furs off—it is warm enough in here, ghost-h

eated, and she is less susceptible to cold than most. "The why of her coup mattered. It always matters."

"As my lord wishes. But—"

"Yes," Lussadh says.

"You were expected, my lord. There were three people to whom you told your intent to personally venture behind the enemy line. Myself, Major Guryin, and Lieutenant Nuawa."

"I know who I've spoken to. Sareha has known me a long time and could anticipate me perfectly well."

"My lord," Ulamat says, "nevertheless should the queen not be ...?"

She gives him a look. He turns quiet. But she shakes herself and sighs. His concern is not misplaced, and Nuawa's newness is not his fault. And it is not an irrational conclusion to reach. "The queen will not address this the way you or I might. I'll handle it. Has Guryin rounded Sareha's soldiers up?"

"Xe's hunting down stragglers. Xer scouts have located a few, some in groups, some alone. Magistrate Sareha knew what was coming and had ordered those loyal to her to flee. Whoever remains in the city will no doubt claim they were but pretending."

Lussadh grimaces. Presses her knuckles against the skin near her wound, careful not to scratch. "Let Guryin know I want a few prisoners kept for interrogation. Some will volunteer a few names rather than go into the kilns. Cross-examining them should help us sort the true from the false." Though under duress those are not always the right names, and ultimately whatever an officer claims, treason is treason. To actively participate or be quietly complicit amounts to much the same. With an uprising it pays to eliminate loose ends, great or small. Sareha had friends, connections that ran through administrative and military branches like hidden rot. The body that is an empire is as vulnerable as any flesh, perhaps even more, manifold more moving parts, manifold more organs held in secret.