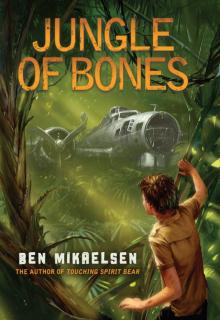

Jungle of Bones

Ben Mikaelsen

I want to dedicate Jungle of Bones to the young and courageous crews who manned the bombers during the Second World War. All citizens of our great country need to learn from these brave men that “freedom is never free.”

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

EPILOGUE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY BEN MIKAELSEN

COPYRIGHT

Dylan slogged through the swamp toward the trees. He needed to find dry ground where he could spend the night again. Still he watched for snakes and crocodiles. The air reeked of rotting undergrowth. All day he had seen birds, rats, possums, and other animals to eat, but no way to catch them. The only critters Dylan could approach were snakes and crocodiles. He knew the snakes might be poisonous, and there was no way he was going to try to catch a crocodile, even a small one.

Before leaving the tall grasses, Dylan ate a few more grasshoppers, and then deliberately headed for a root-tangled path entering the jungle. Soon, the thick, matted screen of overhead vines and leaves muted any fading sunlight that made it through the clouds. For the next hour, Dylan stumbled along a trail, no longer looking down to pick his footing. He had to find some kind of refuge before dark, a place where he could be out in the open but on higher ground. He needed a space where he could lie down and still see wild animals approaching. Hopefully a place with fewer insects.

As the light faded, a brief shower of rain fell. Only a few drops penetrated the dense canopy overhead. Suddenly a sharp pain stabbed Dylan’s ankle. He glanced down in time to see a dark brown snake recoil and slither across the trail and into the undergrowth. “Ouch,” he muttered, crouching. He pulled up his right pant leg to find four small puncture wounds where the snake had sunk its fangs.

Without thinking, Dylan panicked and began running down the trail. But even as he ran, he realized it was probably the dumbest thing he could do after a snake bite. Still he kept running. If he stopped, he would just die here on some muddy overgrown trail in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. By morning, rats would have picked his bones clean. By next week, other critters would have his bones scattered through the forest like twigs and branches. The world would never even know what had happened to Dylan Barstow.

Dylan ran faster. He had to find protection or help.

Overhead the light had faded into darkness. Now the only light came from a hazy moon hanging in the sky like a dim lightbulb. At that very instant, Dylan broke into a clearing similar to the one where he had slept the night before. He walked out away from the darkness of the trees into the moonlight and froze in shock. Ahead were rocks, and next to the rocks stood a tall spiral tree that looked like a big screw. This was the same place he had left early this morning. Without a compass, he had walked all day in a huge circle, only to end up back where he had begun.

Dylan blinked his eyes, as if doing so might make the stupid tree disappear. He shook his head as a wave of despair washed over him, worse than any chill or fever. Dylan screamed, desperate and primal, his voice piercing the hush that had fallen over the clearing. As he finished, tears started down his cheeks, stopping to rest each time he hiccupped with grief. And then a different spasm flooded through his body, and his knees buckled. Dylan collapsed to the ground. The jungle spun in circles. He felt suddenly stiff and cold, as if his body were freezing in a blizzard.

And then there was nothing.

“Remove your hat, son,” the old man said, his voice matter-of-fact, his deep-set eyes intense.

“You’re not my dad!” Dylan snapped. “Get out of my face.”

The man glared at Dylan, hesitated, then turned back to keep watching the parade.

Dylan’s mother, Natalie, turned to him. “Take your hat off,” she said quietly.

When Dylan rolled his eyes, she reached out and grabbed his hat, motioning to the old people marching past. “Those men and women are the VFW, the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Remove your hat to show respect.”

“Bunch of over-the-hill Boy Scouts with their dumb little hats,” Dylan said, motioning. “I can leave my hat on if I want. It’s a free country.”

Frustration clouded Natalie’s eyes as she tucked Dylan’s hat into her purse.

“Give that back,” Dylan demanded.

She ignored him and headed back toward the car.

“Hey, the parade’s not over yet,” Dylan said.

Natalie kept walking.

“What’s the big deal?” Dylan muttered, following her.

When they arrived home, Dylan’s mother worked around the house, giving him the silent treatment. Dylan knew he should feel lucky. Some parents yelled and shouted, or even hit their kids, when they were mad. His mom just clammed up. He could tell whenever she was angry because she quit talking. Dylan stomped up the stairs to his room, whistling for his dog, Zipper, to follow him. His black lab was the only sane thing in his life anymore. Zipper didn’t care what anybody wore or said. He didn’t care what time anybody went to bed or if they skipped school, as long as he could cuddle and get his ears scratched.

Dylan slammed the door to his room and flopped down on his bed. “C’mon up, boy,” he said, coaxing Zipper onto the bed. That was something that bugged his mom; she said Zipper shed too much. But right now Dylan wanted the company. He lay back and stared at the ceiling. It wasn’t like he had killed anybody or stolen anything. All he had done was not take his hat off. Since when was that a capital offense? Dylan looked around his room. He was too mad to play his computer games. Instead he took a tennis ball and bounced it repeatedly off the wall. That was something that really bugged Mom.

Most times Zipper would chase the ball around the room. Tonight, he curled on the bed, watching with lazy eyes.

“Are you giving me the silent treatment, too?” Dylan asked.

Zipper closed his eyes without even wagging his tail.

Natalie called up, “There’s food in the refrigerator if you’re hungry. I want you home tonight.” Before Dylan could answer, the front door closed. Moments later, the car pulled from the driveway.

Dylan threw the tennis ball extra hard one last time. She hadn’t made dinner for him, or said anything about bouncing the ball. What was the big deal not taking his hat off in front of a bunch of old geezers? But deep inside, Dylan knew it was much more than that.

Zipper shifted positions and plopped his nose on Dylan’s lap.

Dylan’s eyes grew glassy as he scratched behind the dog’s ear.

It was after dark when Dylan’s mother finally returned. He could hear her busying around downstairs for almost an hour. Before going to bed, she poked her head in Dylan’s room to make sure he was home.

“What’s wrong? Don’t you trust me?” Dylan shouted as his mom closed the door. She retreated down the stairs without even saying hello.

Dylan’s face flushed with anger. Why did she treat him like some little kid who needed babysitting? He would be in eighth grade this fall, yet she always acted like he was some screw-up who was about to set the house on fire. Dylan crossed the room. If she wanted a screw-up, he would really give her one. He eased his window open and crawled out onto the porch roof. He whispered back, “Zi

pper, stay!” Dylan could hear Zipper whining as he carefully tiptoed down the shingles and over to where a big maple tree grew near the gutter downspout. With practiced ease, he lowered himself to the ground.

He didn’t know where he was going — he just began walking. When he reached the end of the block, an idea struck him. He quickened his pace and ran the next six blocks to the edge of town, where he squeezed under a wood-slatted fence that guarded the front of the local junkyard. Often, when he skipped school, he came out here to wander around the junked cars. He loved cars, any kind of car: antiques, hot rods, sports cars. He especially liked Corvettes — that had been Dad’s favorite car. Dylan could tell just about every model that had ever been made. Not that there were any Corvettes in this junkyard, but there were other old cars that were pretty awesome.

Whenever Dylan wandered through this junkyard, the owner, a guy called Mantz Krogan, watched him as if he thought a crook were trying to steal something. To bug the owner, Dylan always walked extra slowly. During one of his visits, Dylan had noticed six or seven cars parked away from the others in a row beside the garage. He asked about them, and Mantz said they had been fixed up to run and were for sale. When Dylan looked inside the cars, he noticed keys in all the ignitions. That was something he remembered now as he crossed the darkened yard.

He walked straight to an old gray Plymouth in the middle of the row. A dim yard light cast eerie shadows from each car. Peering in, Dylan saw a key chain dangling from the car’s ignition. He took a step back from the Plymouth and stood up straight. Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea. He looked around at the empty and quiet lot. Most people were fast asleep by now, including his mom. If he just took the car for a quick ride and returned it, how would anyone know it was him? Dylan tried the driver’s door. He expected it to be locked, but the handle clicked and the door swung open with a creak. Dylan took this as a sign and crawled inside.

Fumbling in the darkness, he stepped on the clutch, shifted it into neutral, and turned the key. The engine cranked several times before the old Plymouth growled to life. Dylan revved the engine. Grinning with nervousness, he slowly shifted the car into reverse and backed away from the building.

A freshly plowed field surrounded the junkyard, looking like a moonscape in the dim light. Dylan floored the gas pedal and popped the clutch, spinning the tires all the way down the gravel drive that circled the yard. When he reached the field, he twisted the steering wheel to the right and heard the twang of wire as the big car plowed through the fence. Dylan left the lights off — the dim moon made the field look foreboding. Dylan imagined zombies appearing.

This far from the highway, on a dark night, Dylan doubted that anybody would even hear or see him. He shifted into second and floored the gas pedal again. The old Plymouth roared as it bounced across the deep furrows. Again and again the shock absorbers bottomed out, jarring the whole car. Dylan laughed aloud as he spun the wheel and began spinning circles. Dylan called it “cutting donuts.”

Careening around in circles made the dry dirt kick up. Soon, a cloud of dust blocked even the half-moon from witnessing his joyride. In total darkness, Dylan kept the gas pedal pressed to the floor. His mom would be having a batch of kittens if she knew that her “little boy” was out spinning donuts in a farmer’s field. Dylan closed his eyes and tilted his head back. Keeping the gas pedal floored, he smiled. Life was good!

It was nearly five minutes before Dylan opened his eyes again. He noticed a flicker of red through the thick cloud of dust and let up on the gas pedal. As the dust cleared, the moonlight returned, along with a set of headlights. Without the motor revving, Dylan could also hear a siren now. He straightened out the steering wheel and carefully drove out of the vanishing dust cloud.

Facing Dylan waited two patrol cars, red lights flashing, sirens wailing. “Stop the car and get out with your hands up!” an amplified voice shouted over a loudspeaker on top of one of the squad cars. “Get out now!”

Bright headlights blinded Dylan as he braked to a stop and shut off the engine. This was bad. His plan hadn’t been to get caught. He panicked. Maybe he could jump out and run — in the darkness the officers probably couldn’t catch him. But before Dylan could do anything, a deputy ran to the side of the old Plymouth. He jerked the door open and drew his pistol. “Get out with your hands up!” he shouted.

Dylan turned the ignition switch off and raised his hands. An eerie silence hung in the air, along with dust, as he crawled slowly from the car. “I-I was just having a little fun,” he stammered, holding his hands above his head. He recognized the deputy.

“Put your hands on the hood and spread your legs!” the deputy demanded.

Now an officer from the other squad car ran up. He grabbed Dylan’s hands, one at a time, and twisted them behind his back to snap on a pair of handcuffs. “You call this a little fun? Wrecking somebody’s car, running down a fence, and ripping up somebody’s planted field?”

“I’ll pay for it,” Dylan argued, his voice shaking. The handcuffs bit into his wrists.

“You bet you will,” the deputy answered.

Dylan kicked at the dirt in frustration as the officer led him through clouds of dust to the back of the patrol car.

At the detention center, Dylan recognized the tall officer who processed him. He also recognized the small room with a big table where he sat across from the officer for questioning. This was where he had come several times before. Last time it had been for stealing candy bars. You would have thought he’d robbed Fort Knox.

The questioning seemed to last for hours. What was so different about this visit? They already had a file as thick as a phone book on him. Tonight the officer treated him like a real criminal, leaving the handcuffs on him and never cracking a smile. He acted as if he was interviewing a serial killer.

He said this was grand theft auto and would be treated as a felony.

Dylan slumped in his chair and tried not to look at the officer. It wasn’t like he had really stolen a car. He just took an old junker for a little ride. What was so bad about that?

Finally the officer escorted Dylan to a bare white holding room where he flopped himself onto a thin mattress that covered a gray steel bed frame. The only other fixtures were a toilet, a small table, and a chair. A locked metal door guaranteed he wouldn’t leave.

It was a good thing he didn’t have to stay here long, Dylan thought. His mom would come get him out of the detention center soon. That was what she always did. Again, he would be given a warning, but nothing would come of it.

Nearly an hour passed before a lady in a uniform came to Dylan’s holding room. She was a short, dumpy-looking woman with shoes that clopped when she walked. Her hair wrapped behind her head into a bun and she wore a dress that hung to the middle of her shins like a tent. She looked like some kid’s grandmother — probably was. She smiled sweetly as if welcoming him to some fancy hotel. “Your mom won’t be coming down to get you until sometime tomorrow, so make yourself comfortable.”

“What do you mean, tomorrow?”

The lady spoke sincerely. “Well, that means she won’t be coming tonight, because if she came tonight, that wouldn’t be tomorrow. Tomorrow means she is coming on a whole different day, the one after today.”

“I know what tomorrow is!” Dylan snapped.

“Oh,” the woman said, placing a surprised hand over her mouth, “I could have sworn you asked me what I meant by tomorrow. Please accept my apology.”

Dylan kept his cool, but wished he could throw something at this human antique as she left the room. He would love to wipe that smug look off her face. The noise of her key locking the door sounded like the cocking of a rifle.

Dylan walked in angry circles. Why was everyone so uptight? He wondered about his mom. She could have gotten dressed and come right down. Maybe he had pushed her too far. But so what? If this was the straw that broke the camel’s back, maybe it would be fun having a dead camel lying around.

As Dylan stared

at the gray metal door, a knot tightened in his stomach. He had a bad feeling about this whole thing.

By the time his mom showed up the next day, it was almost noon. A deputy unlocked the door and stood waiting as Natalie entered the holding cell. After a night locked up alone, Dylan wanted to unload on her with every name he could think of, but held back. He was smart enough to know he should act really sorry. At least for a couple of days.

Today his mom was quiet, a pained expression making her eyes look tired. She just stood in the doorway and stared at him.

“Aren’t you going to ask me why I did it?” Dylan asked.

“Oh, I already know why you did it,” she said.

“And why is that?”

“Because you think Dylan Barstow is the only person living on the planet who has feelings. Nobody else matters.”

“Mom, I was just out having a little fun,” Dylan explained.

“And why is it that every time Dylan Barstow has fun, somebody else pays or gets hurt? I’m getting really tired of your fun.”

“The world is getting too uptight,” Dylan said, standing up. “Let’s get out of this hole.”

“You’re not coming home today. I came late this morning because I’ve spent the last two hours trying to convince Mr. Krogan not to press charges. Lucky for you, he agreed, but only if you’re kept far away from his cars. I also called your uncle Todd. He’ll be flying in tomorrow to take you back to Oregon. You’re spending the rest of the summer with him.”

Dylan glanced at the deputy blocking the door as his thoughts raced. Uncle Todd was his rich uncle who lived near Portland, Oregon. He looked like a bulldog on two feet. His neck came straight down from his ears to his massive shoulders. The guy still ran, lifted weights, and shaved his head almost bald, the same as when he was in the Marines.

“Why did you call him?” Dylan demanded. “I’m not going to Oregon for the rest of the summer.”

“It’s that or get tried in juvenile court. Maybe you don’t quite understand how much trouble you’re in. You committed a felony last night. I can only imagine what your father would have thought of this.”