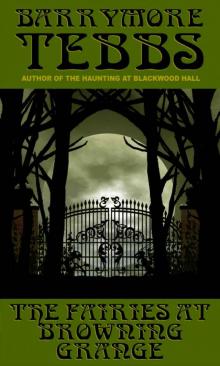

The Fairies at Browning Grange

Barrymore Tebbs

The Fairies at Browning Grange

By Barrymore Tebbs

© 2012 Barrymore Tebbs. All rights reserved.

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

ONE

I awoke instantly, startled from sleep by the staccato knock on the door. I sat up in bed as the young man burst into the room.

“Thank heaven you are awake,” he said without preamble or apology. “We need your help at once.”

The edges of sleep slipped rapidly away. I remembered his name, this tight-faced fellow, stiff in his starched livery. It was Rupert. And I knew where I was. A canopied four-poster bed, a spacious room, dark panels hung with somber paintings: a bedroom in the house at Browning Grange. Fragments came back to me: the storm, a power failure, Olive, the relentless screams of Mrs. Conklin’s labor…

Dread fingered the nape of my neck. The baby. I knew before I opened my mouth that something had happened to the baby. Rupert had my full attention.

“What is it?” I asked.

“It’s the baby, sir.” Rupert confirmed my fear. His features were pinched, his skin flushed with worry. “It’s disappeared.”

I leapt from the bed, turning my back on Rupert as I tore the nightshirt over my head. He offered to help me dress. I shook my head vigorously. I was flattered that he wished to treat me as any other member of the family, but I assured him I was quite comfortable to dress myself and would feel far less so if I were to allow another man to assist me with my wardrobe. If I had been raised in a household such as Browning Grange, I would have readily accepted. But I am a simple man by nature and chose to cling to my own humble traditions.

He was a footman after all, not a valet.

I stood at the window as I buttoned my shirt. The drapes were parted but the view offered nothing but a mass of impenetrable white fog. The windows were open. The air was refreshingly clear. The storm had done its job and expelled the heat which had plagued the valley for nearly a week. The events of the night before were as hazy as the world beyond the window. More puzzle pieces came back to me: Brunswick’s endless barking, Freddie scampering gleefully through the halls, the sizzle and pop when the house was plunged into utter darkness, Olive pulling me into an unused room… these images tumbled against one another until it was difficult to determine what was real and what was not. But it was real, wasn’t it? Every last bit. The baby’s disappearance affirmed as much.

Despite Rupert’s protests, I insisted on following him into the servant’s quarters. I refused to be treated as a guest any longer. There was work to be done, and I would gladly help.

Standing at the table in the servants’ eating room, I ate a plate of sausages and made quick work of a cup of strong tea. Olive was nowhere in sight. Of course she wouldn’t be. She was shut away with her sister, consoling the poor woman. I couldn’t imagine the shock and terror of having one’s child stolen from it’s cradle mere hours after it’s birth. Mrs. Conklin must be mad with misery and panic. My heart ached for her as much as it longed for Olive. If I had known then that I would never see Olive again, would I have gone to her, declaring my undying love for her? You’ll think me mad when you learn that I had known her only a few days, but stay and listen awhile. The tale grows stranger still.

Mr. Brooks – the butler – dispatched the servants and myself to search the house. Freddie was there, demanding that he should help search for the baby, after all it was his little brother. Rupert, however, gave Miss Enfield instructions to take the boy back to the nursery. A five-year-old with Freddie’s restless energy would be more hindrance than assistance. The sour face he made when the governess dragged him by the arm!

At another time I would have been impressed by the size and opulence of the house. I had seen very little of it the night before. I was teamed with the young hall boy named Georgie who seemed as uncomfortable with the business of stepping in and out of unused rooms as I; poking our heads into cupboards, beneath beds and inside of bureau drawers, anywhere small enough to hide a newborn baby. We made our way up a steep, narrow staircase and came to the upper rooms of the house where most of the servants were quartered. Mr. Brooks had given orders that no room should be left unsearched. In a household as large as this, no servant was above suspicion.

The search of the house took more than an hour and then it was on to the formidable portion of our task, the search of the grounds. I have no notion of how large the estate actually is, but from what I had seen on my visits the past two days I surmised that Browning Grange could not be thoroughly searched in a single day. If we were fortunate enough to find the baby at all, would it be face-down in the stream behind the house or stuffed inside a stack of hay in the barn?

Or at the bottom of Goblin Hollow?

To make matters worse, the fog had not yet lifted, nor did it appear it would anytime soon. It must have been late morning when the search of the grounds began. There were men and boys of all ages, from twelve-year-old Georgie to the head gardener, who by appearances must have been well into his eighties and toddled along at an alarmingly slow pace.

We spread out across the grounds. The bleached white fog billowed and swirled around us. I turned, expecting to see the towers and turrets of the house rising out of the mist behind me, but I did not. I looked this way and that. I could not have been more than twenty feet from the house yet already I had lost my sense of direction. I knew the others had as well, for the men began to call to one another from their various positions, their voices eerie in the otherwise soft silence. A few of them had brought along electric torches – a lot of good they did.

Except for the occasional call of the men’s voices drifting further apart, I might have been alone. It was as if I had been swallowed up inside the mist, a sailor alone on a sea of uncertain fate. If Emily or Freddie had been with me, they would have guided me through the meadow which they had crossed a thousand times before. I stumbled forward blindly with nothing left to guide me but my instincts.

I kept my gaze on the ground, the length of my stride steadily increasing until I was able to move with confidence. It was as if some unseen force led me by the hand. Eventually I saw the thick undergrowth and the gnarled roots of trees and knew I had come to the edge of the forest; here was the mouth to the path the children had followed.

Now my pace began to slow. I had to pay strict attention to where I placed my feet. The forest was as old as the earth itself, the floor a riot of dangerous undergrowth. One wrong turn and I would twist an ankle or break a limb. I held onto the trees and branches and used them to pull myself deeper and deeper into the forest. Here, with no sunlight to illuminate it, the mist became a dark cocoon.

A whisper sounded close behind me, not unlike those taunting, sibilant voices I had heard at twilight at the bottom of Goblin Hollow. My head whipped around. My body turned too suddenly and I lost my balance. A large root reached from within the earth causing me to trip and fall. I lay at the base of the tree. An instant burning seared my leg. Winded, I lay back against the massive trunk. I knew this tree only too well. I shut my eyes against the pain, and thought of Olive.

* * *

I am a schoolmaster by trade, but on holidays and weekends I can be seen pedaling about the district on my bicycle, camera in tow, tripod slung across my back, taking photographs of the people and places in and around our country village. Neighbors are often curious about my work, which I display on the walls of Mrs. Spencer’s stationery shop which also serves as the local post office. I manage to sell the odd framed photograph here and there, but more frequently I a

m approached to photograph a family, or a husband and his new bride, and of course, children and babies.

I was in Mrs. Spencer’s shop hanging two newly framed photographs when I saw the children. I did not know their names but recognized the girl as one of the children from Browning Grange, the great house nestled within a walled estate in the forest some ten miles outside the village. The children of Browning Grange did not go to school with the rest of the village children. The Conklins were wealthy and most likely had a governess, although only for the girl who appeared to be about ten years of age. The boy was no more than five, and I believe it was the first time I had ever set eyes on him. It had been several years since I’d seen the girl; that was how often the Conklin children made an appearance in the village. If I had ever seen the boy, he would have been no more than a baby, but one could easily tell they were brother and sister. They each had the same plump faces and vivid blue eyes and the kind of flaxen blond hair which defied brushing and is frequently at the mercy of the winds. The girl was dressed in a bright yellow frock with matching ribbons in her hair and the boy in a shirt as blue as the bright summer sky.

The children were captivated by a photograph I had just hung on the wall. In the photograph, one of my students, a girl of about twelve years of age, read from a book of tales to two younger girls scarcely old enough to read on their own. The camera had captured Rebecca’s face as she gave life to the voice of some ogre or troll, and the two little ones gazed upon the pages of the book in wonder.

“Did you take the photograph?” asked the girl.

“Yes, I did. Do you like it?”

“Mmm,” she said. There was a sparkle in her eyes as she studied the photograph, as if she saw something in its imagery that captured her imagination.

“I like it too,” said the boy. Smiling, I ruffled his hair.

“Could you take a photograph of my brother and me like that?”

“I certainly could, but I don’t have my camera with me at the moment. What are your names?”

“I’m Emily, and this is Freddie.”

“How old are you Freddie?” I asked.

“I’m five.”

What charming creatures they were. “Are you the Conklin children from Browning Grange?”

Emily’s eyes brightened. “How did you know?”

“Because I am the schoolmaster, and I know the faces and names of all the children in the village, even the ones who aren’t old enough to go to school. I know everyone’s names except for yours. But now I do. My name is Mr. Warrick.”

The children cordially shook my hand. I was delighted at how mannerly they were.

“And I am Miss Gibbs,” a woman’s voice behind me said. I stood and turned to give her my attention.

She was dressed rather more modern than we are accustomed to seeing here in the village, with a flat straw hat and a waistcoat over a shirt with a man’s style tie which was quite the fashion in the larger cities, especially where women stood in solidarity with Women’s Suffrage. She had dark brown hair and equally dark eyes, round and luminous in an oval face. Despite her somewhat masculine attire, I found her appearance most becoming, and introduced myself to her as well, concluding, “You must be the governess at Browning Grange.”

“Heavens, no!” she laughed. “I am Mrs. Conklin’s sister, Olive. Eleanor is expecting another child, and as she lost her husband in the spring and has taken to her bed since Fredrick’s death, the doctor thought it best that I come to be with her until after the birth of the child.”

“Yes, I see.” Indeed, on closer inspection I could see the family resemblance. “I do apologize for making such a bold assumption. I heard about Mr. Conklin’s death, though I did not know him. I am very sorry for your loss.”

Olive waved her hand dismissively as if her brother-in-law’s death was inconsequential. “Please don’t feel obliged to offer condolences on my account. Fredrick and I were not close. I am here merely on the recommendation of Dr. Meadows. As you can imagine, Eleanor has been in a state of shock since the accident.”

“Accident?” I prompted, more out of a selfish interest in keeping the conversation going than any real curiosity about people whom I did not know.

“He was killed during a hunting party: shot by his own gun, no less. But it serves him right. Men have no business hunting merely for sport.”

I wasn’t certain whether I should be appalled or impressed with her matter-of-fact opinion, but the fact that she was not afraid to speak her mind was in fact quite admirable.

“But that is what a grange is for, is it not,” I said, “for hunting?”

“We English have a way of clinging to tradition even if it no longer has any bearing on our modern lives,” she said. “This is the twentieth century, after all, and if we are to progress as a nation we must learn to part with outdated ways of thinking and embrace the future.”

My face must have registered my discomfort at the direction in which the conversation had turned for I was afraid she would launch into a speech about women’s rights. I whole-heartedly supported their beliefs. My own sister was involved with the movement in London. I received frequent letters and telephone calls about the cause, enough that I would be bored to tears to discuss it any further, despite the fact that I found Miss Gibbs to be quite attractive. Thankfully, I was spared further discourse when young Emily said, “When can you take our photograph?”

“Emily,” Miss Gibbs chastised, “do you have money to pay to have your photograph taken?”

“It’s quite all right,” I said with a smile for Emily. “Under many circumstances I take photographs because I want to, not for profit. I would be delighted to take the children’s picture. Perhaps we should wait until the baby arrives and we could take a photograph of the three children together to present to their mother.”

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed Emily. “Could we?”

Miss Gibbs smiled at me in such a way that I was somewhat taken aback. If a man had eyed a woman like that he might be accused of verging on some impropriety. “Perhaps I could persuade you to visit Browning Grange with your camera before the baby’s arrival.” She looked down at the children. “Don’t you suppose he would like to come along and photograph the fairies?”

The children nearly exploded with excitement. “Oh, yes! That’s a grand idea!”

I couldn’t help a patronizing smile, but when I looked from their eyes to Miss Gibbs, I saw that she was in earnest.

“Surely you are not serious?”

“I am.”

I wiped a hand over my jaw. “Do you mean to say there are fairies at Browning Grange?”

“I do.”

“Have you seen them?”

“I have.”

She was pulling my leg. It was only some ploy to lure me to the estate for reasons known only to her.

“What sort of fairies are they? Pixies?”

“Oh, goblins –” said Freddie.

“– Gnomes and gremlins –” continued Emily.

“But goblins mostly,” concluded Freddie.

I looked to Miss Gibbs for confirmation. She nodded.

“Wait here a moment,” I said, and I went outside to where my bicycle leant against the wall of Mrs. Spencer’s shop. I unhooked the satchel I keep attached behind the bicycle seat and carried it into the shop.

In the satchel I always carry a few items dear to me: a favored photograph of my dear mother, a notebook in which to jot details of various photographs I take, and a small handful of publications which I cherish for their reproduction of certain photographs which inspire me. Here, I also carry a treasured copy of the December issue of The Strand Magazine.

I have devoutly purchased The Strand ever since I was given a copy for Christmas in 1901 which contained the fourth installment of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes adventure, The Hound of the Baskervilles. The impression this story made on my eleven-year-old mind with its moorland mists, family legends, and moments of white-knuckle suspense that caused me

to nearly ruin the pages of the magazine as I clutched them in my sweaty hands was an indelible one and I have been an admirer of Mr. Doyle’s writing ever since. Mr. Doyle has made no secret of his belief in Spiritualism, and while I admit I am fascinated by the ideas when they are used to maximum effect in romantic tales, I am prone to believe the entire thing a lot of froth and bubble. I did not quite know what to make of Mr. Doyle’s essay on fairies as presented in this particular issue, and at heart I believed the accompanying photographs of fairies taken by the children at Cottingley were little more than ingenious fakes. This belief, however, did not prevent me from treasuring this particular issue and carrying it with me on my travels.

I knelt beside the Conklin children and opened the magazine to a picture of a little girl surrounded by a host of fairies dancing merrily before her less-than-astonished gaze.

“Do the fairies at Browning Grange look like this?”

“Oh, no!” the children chorused together and burst into gales of laughter.

I looked bemusedly at Miss Gibbs.

“They look nothing like that at all,” she said.

“Can either of you draw a picture for me?”

“I can!” declared Freddie.

He lay down on the floor with my notebook and pencil. I stood over him, impressed at how well the five-year-old was able to draw. The picture he drew was exactly as I imagined it would be. The spindly body had an overly large head and two large black eyes. I glanced again at Miss Gibbs for confirmation.

“Is this what you have seen?”

“More or less.”

“How often have you seen them?”

“All the time!” said the children.

“And you?”

“Only on a few occasions,” said Miss Gibbs. “They are difficult to see. I believe that children are more in tune with the spirit world, and more willing to believe what they see. You would be able to see them as well, had you not closed your mind already.”