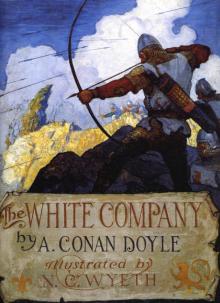

The White Company

Arthur Conan Doyle

Produced by Charles Keller, Carlo Traverso, Tonya Allenand Samuel S. Johnson

THE WHITE COMPANY

By Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

CONTENTS.

I. How the Black Sheep came forth from the Fold II. How Alleyne Edricson came out into the World III. How Hordle John cozened the Fuller of Lymington IV. How the Bailiff of Southampton Slew the Two Masterless Men IV. How a Strange Company Gathered at the "Pied Merlin" VI. How Samkin Aylward Wagered his Feather-bed VII. How the Three Comrades Journeyed through the Woodlands VIII. The Three Friends IX. How Strange Things Befell in Minstead Wood X. How Hordle John Found a Man whom he Might Follow XI. How a Young Shepherd had a Perilous Flock XII. How Alleyne Learned More than he could Teach XIII. How the White Company set forth to the Wars XIV. How Sir Nigel sought for a Wayside Venture XV. How the Yellow Cog sailed forth from Lepe XVI. How the Yellow Cog fought the Two Rover Galleys XVII. How the Yellow Cog crossed the Bar of Gironde XVIII. How Sir Nigel Loring put a Patch upon his Eye XIX. How there was Stir at the Abbey of St. Andrew's XX. How Alleyne Won his Place in an Honorable Guild XXI. How Agostino Pisano Risked his Head XXII. How the Bowmen held Wassail at the "Rose de Guienne" XXIII. How England held the Lists at Bordeaux XXIV. How a Champion came forth from the East XXV. How Sir Nigel wrote to Twynham Castle XXVI. How the Three Comrades Gained a Mighty Treasure XXVII. How Roger Club-foot was Passed into Paradise XXVIII. How the Comrades came over the Marches of France XXIX. How the Blessed Hour of Sight Came to the Lady Tiphaine XXX. How the Brushwood Men came to the Chateau of Villefranche XXXI. How Five Men held the Keep of Villefranche XXXII. How the Company took Counsel Round the Fallen Tree XXXIII. How the Army made the Passage of Roncesvalles XXXIV. How the Company Made Sport in the Vale of Pampeluna XXXV. How Sir Nigel Hawked at an Eagle XXXVI. How Sir Nigel Took the Patch from his Eye XXXVII. How the White Company came to be Disbanded XXXVIII. Of the Home-coming to Hampshire

CHAPTER I. HOW THE BLACK SHEEP CAME FORTH FROM THE FOLD.

The great bell of Beaulieu was ringing. Far away through the forestmight be heard its musical clangor and swell. Peat-cutters on Blackdownand fishers upon the Exe heard the distant throbbing rising and fallingupon the sultry summer air. It was a common sound in those parts--ascommon as the chatter of the jays and the booming of the bittern. Yetthe fishers and the peasants raised their heads and looked questions ateach other, for the angelus had already gone and vespers was still faroff. Why should the great bell of Beaulieu toll when the shadows wereneither short nor long?

All round the Abbey the monks were trooping in. Under the longgreen-paved avenues of gnarled oaks and of lichened beeches thewhite-robed brothers gathered to the sound. From the vine-yard andthe vine-press, from the bouvary or ox-farm, from the marl-pits andsalterns, even from the distant iron-works of Sowley and the outlyinggrange of St. Leonard's, they had all turned their steps homewards. Ithad been no sudden call. A swift messenger had the night before spedround to the outlying dependencies of the Abbey, and had left thesummons for every monk to be back in the cloisters by the third hourafter noontide. So urgent a message had not been issued within thememory of old lay-brother Athanasius, who had cleaned the Abbey knockersince the year after the Battle of Bannockburn.

A stranger who knew nothing either of the Abbey or of its immenseresources might have gathered from the appearance of the brothers someconception of the varied duties which they were called upon to perform,and of the busy, wide-spread life which centred in the old monastery.As they swept gravely in by twos and by threes, with bended heads andmuttering lips there were few who did not bear upon them some signs oftheir daily toil. Here were two with wrists and sleeves all spottedwith the ruddy grape juice. There again was a bearded brother witha broad-headed axe and a bundle of faggots upon his shoulders, whilebeside him walked another with the shears under his arm and the whitewool still clinging to his whiter gown. A long, straggling troop borespades and mattocks while the two rearmost of all staggered along undera huge basket o' fresh-caught carp, for the morrow was Friday, and therewere fifty platters to be filled and as many sturdy trenchermen behindthem. Of all the throng there was scarce one who was not labor-stainedand weary, for Abbot Berghersh was a hard man to himself and to others.

Meanwhile, in the broad and lofty chamber set apart for occasions ofimport, the Abbot himself was pacing impatiently backwards and forwards,with his long white nervous hands clasped in front of him. His thin,thought-worn features and sunken, haggard cheeks bespoke one who hadindeed beaten down that inner foe whom every man must face, but had nonethe less suffered sorely in the contest. In crushing his passions he hadwell-nigh crushed himself. Yet, frail as was his person there gleamedout ever and anon from under his drooping brows a flash of fierceenergy, which recalled to men's minds that he came of a fighting stock,and that even now his twin-brother, Sir Bartholomew Berghersh, was oneof the most famous of those stern warriors who had planted the Cross ofSt. George before the gates of Paris. With lips compressed and cloudedbrow, he strode up and down the oaken floor, the very genius andimpersonation of asceticism, while the great bell still thundered andclanged above his head. At last the uproar died away in three last,measured throbs, and ere their echo had ceased the Abbot struck a smallgong which summoned a lay-brother to his presence.

"Have the brethren come?" he asked, in the Anglo-French dialect used inreligious houses.

"They are here," the other answered, with his eyes cast down and hishands crossed upon his chest.

"All?"

"Two and thirty of the seniors and fifteen of the novices, most holyfather. Brother Mark of the Spicarium is sore smitten with a fever andcould not come. He said that--"

"It boots not what he said. Fever or no, he should have come at my call.His spirit must be chastened, as must that of many more in this Abbey.You yourself, brother Francis, have twice raised your voice, so it hathcome to my ears, when the reader in the refectory hath been dealing withthe lives of God's most blessed saints. What hast thou to say?"

The lay-brother stood meek and silent, with his arms still crossed infront of him.

"One thousand Aves and as many Credos, said standing with armsoutstretched before the shrine of the Virgin, may help thee to rememberthat the Creator hath given us two ears and but one mouth, as a tokenthat there is twice the work for the one as for the other. Where is themaster of the novices?"

"He is without, most holy father."

"Send him hither."

The sandalled feet clattered over the wooden floor, and the iron-bounddoor creaked upon its hinges. In a few moments it opened again to admita short square monk with a heavy, composed face and an authoritativemanner.

"You have sent for me, holy father?"

"Yes, brother Jerome, I wish that this matter be disposed of with aslittle scandal as may be, and yet it is needful that the example shouldbe a public one." The Abbot spoke in Latin now, as a language which wasmore fitted by its age and solemnity to convey the thoughts of two highdignitaries of the order.

"It would, perchance, be best that the novices be not admitted,"suggested the master. "This mention of a woman may turn their minds fromtheir pious meditations to worldly and evil thoughts."

"Woman! woman!" groaned the Abbot. "Well has the holy Chrysostom termedthem _radix malorum_. From Eve downwards, what good hath come from anyof them? Who brings the plaint?"

"It is brother Ambrose."

"A holy and devout young man."

"A light and a pattern to every novice."

"Let the matter be brought to an issue then according to our old-timemonasti

c habit. Bid the chancellor and the sub-chancellor lead in thebrothers according to age, together with brother John, the accused, andbrother Ambrose, the accuser."

"And the novices?"

"Let them bide in the north alley of the cloisters. Stay! Bid thesub-chancellor send out to them Thomas the lector to read unto themfrom the 'Gesta beati Benedicti.' It may save them from foolish andpernicious babbling."

The Abbot was left to himself once more, and bent his thin gray faceover his illuminated breviary. So he remained while the senior monksfiled slowly and sedately into the chamber seating themselves upon thelong oaken benches which lined the wall on either side. At the furtherend, in two high chairs as large as that of the Abbot, though hardly aselaborately carved, sat the master of the novices and the chancellor,the latter a broad and portly priest, with dark mirthful eyes and athick outgrowth of crisp black hair all round his tonsured head. Betweenthem stood a lean, white-faced brother who appeared to be ill at ease,shifting his feet from side to side and tapping his chin nervously withthe long parchment roll which he held in his hand. The Abbot, from hispoint of vantage, looked down on the two long lines of faces, placid andsun-browned for the most part, with the large bovine eyes and unlinedfeatures which told of their easy, unchanging existence. Then he turnedhis eager fiery gaze upon the pale-faced monk who faced him.

"This plaint is thine, as I learn, brother Ambrose," said he. "May theholy Benedict, patron of our house, be present this day and aid us inour findings! How many counts are there?"

"Three, most holy father," the brother answered in a low and quaveringvoice.

"Have you set them forth according to rule?"

"They are here set down, most holy father, upon a cantle of sheep-skin."

"Let the sheep-skin be handed to the chancellor. Bring in brother John,and let him hear the plaints which have been urged against him."

At this order a lay-brother swung open the door, and two otherlay-brothers entered leading between them a young novice of the order.He was a man of huge stature, dark-eyed and red-headed, with a peculiarhalf-humorous, half-defiant expression upon his bold, well-markedfeatures. His cowl was thrown back upon his shoulders, and his gown,unfastened at the top, disclosed a round, sinewy neck, ruddy and cordedlike the bark of the fir. Thick, muscular arms, covered with a reddishdown, protruded from the wide sleeves of his habit, while his whiteshirt, looped up upon one side, gave a glimpse of a huge knotty leg,scarred and torn with the scratches of brambles. With a bow to theAbbot, which had in it perhaps more pleasantry than reverence, thenovice strode across to the carved prie-dieu which had been set apartfor him, and stood silent and erect with his hand upon the gold bellwhich was used in the private orisons of the Abbot's own household. Hisdark eyes glanced rapidly over the assembly, and finally settled with agrim and menacing twinkle upon the face of his accuser.

The chancellor rose, and having slowly unrolled the parchment-scroll,proceeded to read it out in a thick and pompous voice, while a subduedrustle and movement among the brothers bespoke the interest with whichthey followed the proceedings.

"Charges brought upon the second Thursday after the Feast of theAssumption, in the year of our Lord thirteen hundred and sixty-six,against brother John, formerly known as Hordle John, or John of Hordle,but now a novice in the holy monastic order of the Cistercians. Readupon the same day at the Abbey of Beaulieu in the presence of the mostreverend Abbot Berghersh and of the assembled order.

"The charges against the said brother John are the following, namely, towit:

"First, that on the above-mentioned Feast of the Assumption, small beerhaving been served to the novices in the proportion of one quart toeach four, the said brother John did drain the pot at one draught tothe detriment of brother Paul, brother Porphyry and brother Ambrose,who could scarce eat their none-meat of salted stock-fish on account oftheir exceeding dryness."

At this solemn indictment the novice raised his hand and twitched hislip, while even the placid senior brothers glanced across at each otherand coughed to cover their amusement. The Abbot alone sat gray andimmutable, with a drawn face and a brooding eye.

"Item, that having been told by the master of the novices that he shouldrestrict his food for two days to a single three-pound loaf of bran andbeans, for the greater honoring and glorifying of St. Monica, mother ofthe holy Augustine, he was heard by brother Ambrose and others to saythat he wished twenty thousand devils would fly away with the saidMonica, mother of the holy Augustine, or any other saint who camebetween a man and his meat. Item, that upon brother Ambrose reprovinghim for this blasphemous wish, he did hold the said brother facedownwards over the piscatorium or fish-pond for a space during whichthe said brother was able to repeat a pater and four aves for the betterfortifying of his soul against impending death."

There was a buzz and murmur among the white-frocked brethren at thisgrave charge; but the Abbot held up his long quivering hand. "Whatthen?" said he.

"Item, that between nones and vespers on the feast of James the Less thesaid brother John was observed upon the Brockenhurst road, near the spotwhich is known as Hatchett's Pond in converse with a person of the othersex, being a maiden of the name of Mary Sowley, the daughter of theKing's verderer. Item, that after sundry japes and jokes the saidbrother John did lift up the said Mary Sowley and did take, carry, andconvey her across a stream, to the infinite relish of the devil and theexceeding detriment of his own soul, which scandalous and wilful fallingaway was witnessed by three members of our order."

A dead silence throughout the room, with a rolling of heads andupturning of eyes, bespoke the pious horror of the community.

The Abbot drew his gray brows low over his fiercely questioning eyes.

"Who can vouch for this thing?" he asked.

"That can I," answered the accuser. "So too can brother Porphyry, whowas with me, and brother Mark of the Spicarium, who hath been so muchstirred and inwardly troubled by the sight that he now lies in a feverthrough it."

"And the woman?" asked the Abbot. "Did she not break into lamentationand woe that a brother should so demean himself?"

"Nay, she smiled sweetly upon him and thanked him. I can vouch it and socan brother Porphyry."

"Canst thou?" cried the Abbot, in a high, tempestuous tone. "Canst thouso? Hast forgotten that the five-and-thirtieth rule of the order is thatin the presence of a woman the face should be ever averted and the eyescast down? Hast forgot it, I say? If your eyes were upon your sandals,how came ye to see this smile of which ye prate? A week in your cells,false brethren, a week of rye-bread and lentils, with double lauds anddouble matins, may help ye to remembrance of the laws under which yelive."

At this sudden outflame of wrath the two witnesses sank their faces onto their chests, and sat as men crushed. The Abbot turned his angry eyesaway from them and bent them upon the accused, who met his searchinggaze with a firm and composed face.

"What hast thou to say, brother John, upon these weighty things whichare urged against you?"

"Little enough, good father, little enough," said the novice, speakingEnglish with a broad West Saxon drawl. The brothers, who were Englishto a man, pricked up their ears at the sound of the homely and yetunfamiliar speech; but the Abbot flushed red with anger, and struck hishand upon the oaken arm of his chair.

"What talk is this?" he cried. "Is this a tongue to be used within thewalls of an old and well-famed monastery? But grace and learning haveever gone hand in hand, and when one is lost it is needless to look forthe other."

"I know not about that," said brother John. "I know only that the wordscome kindly to my mouth, for it was the speech of my fathers before me.Under your favor, I shall either use it now or hold my peace."

The Abbot patted his foot and nodded his head, as one who passes a pointbut does not forget it.

"For the matter of the ale," continued brother John, "I had come in hotfrom the fields and had scarce got the taste of the thing beforemine eye lit upon the bottom of the pot. It may be, too, that

I spokesomewhat shortly concerning the bran and the beans, the same being poorprovender and unfitted for a man of my inches. It is true also that Idid lay my hands upon this jack-fool of a brother Ambrose, though, asyou can see, I did him little scathe. As regards the maid, too, it istrue that I did heft her over the stream, she having on her hosen andshoon, whilst I had but my wooden sandals, which could take no hurt fromthe water. I should have thought shame upon my manhood, as well as mymonkhood, if I had held back my hand from her." He glanced around ashe spoke with the half-amused look which he had worn during the wholeproceedings.

"There is no need to go further," said the Abbot. "He has confessed toall. It only remains for me to portion out the punishment which is dueto his evil conduct."

He rose, and the two long lines of brothers followed his example,looking sideways with scared faces at the angry prelate.

"John of Hordle," he thundered, "you have shown yourself during the twomonths of your novitiate to be a recreant monk, and one who is unworthyto wear the white garb which is the outer symbol of the spotless spirit.That dress shall therefore be stripped from thee, and thou shalt be castinto the outer world without benefit of clerkship, and without lot orpart in the graces and blessings of those who dwell under the care ofthe Blessed Benedict. Thou shalt come back neither to Beaulieu nor toany of the granges of Beaulieu, and thy name shall be struck off thescrolls of the order."

The sentence appeared a terrible one to the older monks, who had becomeso used to the safe and regular life of the Abbey that they would havebeen as helpless as children in the outer world. From their piousoasis they looked dreamily out at the desert of life, a place full ofstormings and strivings--comfortless, restless, and overshadowed byevil. The young novice, however, appeared to have other thoughts, forhis eyes sparkled and his smile broadened. It needed but that to addfresh fuel to the fiery mood of the prelate.

"So much for thy spiritual punishment," he cried. "But it is to thygrosser feelings that we must turn in such natures as thine, and asthou art no longer under the shield of holy church there is the lessdifficulty. Ho there! lay-brothers--Francis, Naomi, Joseph--seize himand bind his arms! Drag him forth, and let the foresters and the portersscourge him from the precincts!"

As these three brothers advanced towards him to carry out the Abbot'sdirection, the smile faded from the novice's face, and he glanced rightand left with his fierce brown eyes, like a bull at a baiting. Then,with a sudden deep-chested shout, he tore up the heavy oaken prie-dieuand poised it to strike, taking two steps backward the while, that nonemight take him at a vantage.

"By the black rood of Waltham!" he roared, "if any knave among you laysa finger-end upon the edge of my gown, I will crush his skull like afilbert!" With his thick knotted arms, his thundering voice, and hisbristle of red hair, there was something so repellent in the man thatthe three brothers flew back at the very glare of him; and the two rowsof white monks strained away from him like poplars in a tempest. TheAbbot only sprang forward with shining eyes; but the chancellor and themaster hung upon either arm and wrested him back out of danger's way.

"He is possessed of a devil!" they shouted. "Run, brother Ambrose,brother Joachim! Call Hugh of the Mill, and Woodman Wat, and Raoul withhis arbalest and bolts. Tell them that we are in fear of our lives! Run,run! for the love of the Virgin!"

But the novice was a strategist as well as a man of action. Springingforward, he hurled his unwieldy weapon at brother Ambrose, and, as deskand monk clattered on to the floor together, he sprang through the opendoor and down the winding stair. Sleepy old brother Athanasius, atthe porter's cell, had a fleeting vision of twinkling feet and flyingskirts; but before he had time to rub his eyes the recreant had passedthe lodge, and was speeding as fast as his sandals could patter alongthe Lyndhurst Road.