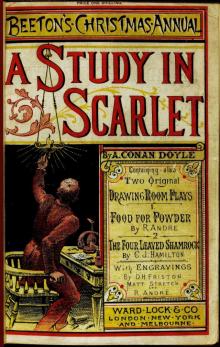

A Study in Scarlet

Arthur Conan Doyle

A STUDY IN SCARLET.

PART I.

(_Being a reprint from the reminiscences of_ JOHN H. WATSON, M.D., _lateof the Army Medical Department._) [2]

CHAPTER I. MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES.

IN the year 1878 I took my degree of Doctor of Medicine of theUniversity of London, and proceeded to Netley to go through the courseprescribed for surgeons in the army. Having completed my studies there,I was duly attached to the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers as AssistantSurgeon. The regiment was stationed in India at the time, and beforeI could join it, the second Afghan war had broken out. On landing atBombay, I learned that my corps had advanced through the passes, andwas already deep in the enemy's country. I followed, however, with manyother officers who were in the same situation as myself, and succeededin reaching Candahar in safety, where I found my regiment, and at onceentered upon my new duties.

The campaign brought honours and promotion to many, but for me it hadnothing but misfortune and disaster. I was removed from my brigade andattached to the Berkshires, with whom I served at the fatal battle ofMaiwand. There I was struck on the shoulder by a Jezail bullet, whichshattered the bone and grazed the subclavian artery. I should havefallen into the hands of the murderous Ghazis had it not been for thedevotion and courage shown by Murray, my orderly, who threw me across apack-horse, and succeeded in bringing me safely to the British lines.

Worn with pain, and weak from the prolonged hardships which I hadundergone, I was removed, with a great train of wounded sufferers, tothe base hospital at Peshawar. Here I rallied, and had already improvedso far as to be able to walk about the wards, and even to bask a littleupon the verandah, when I was struck down by enteric fever, that curseof our Indian possessions. For months my life was despaired of, andwhen at last I came to myself and became convalescent, I was so weak andemaciated that a medical board determined that not a day should be lostin sending me back to England. I was dispatched, accordingly, in thetroopship "Orontes," and landed a month later on Portsmouth jetty, withmy health irretrievably ruined, but with permission from a paternalgovernment to spend the next nine months in attempting to improve it.

I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free asair--or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day willpermit a man to be. Under such circumstances, I naturally gravitated toLondon, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers ofthe Empire are irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time ata private hotel in the Strand, leading a comfortless, meaninglessexistence, and spending such money as I had, considerably more freelythan I ought. So alarming did the state of my finances become, thatI soon realized that I must either leave the metropolis and rusticatesomewhere in the country, or that I must make a complete alteration inmy style of living. Choosing the latter alternative, I began by makingup my mind to leave the hotel, and to take up my quarters in some lesspretentious and less expensive domicile.

On the very day that I had come to this conclusion, I was standing atthe Criterion Bar, when some one tapped me on the shoulder, and turninground I recognized young Stamford, who had been a dresser under me atBarts. The sight of a friendly face in the great wilderness of London isa pleasant thing indeed to a lonely man. In old days Stamford had neverbeen a particular crony of mine, but now I hailed him with enthusiasm,and he, in his turn, appeared to be delighted to see me. In theexuberance of my joy, I asked him to lunch with me at the Holborn, andwe started off together in a hansom.

"Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?" he asked inundisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets."You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut."

I gave him a short sketch of my adventures, and had hardly concluded itby the time that we reached our destination.

"Poor devil!" he said, commiseratingly, after he had listened to mymisfortunes. "What are you up to now?"

"Looking for lodgings." [3] I answered. "Trying to solve the problemas to whether it is possible to get comfortable rooms at a reasonableprice."

"That's a strange thing," remarked my companion; "you are the second manto-day that has used that expression to me."

"And who was the first?" I asked.

"A fellow who is working at the chemical laboratory up at the hospital.He was bemoaning himself this morning because he could not get someoneto go halves with him in some nice rooms which he had found, and whichwere too much for his purse."

"By Jove!" I cried, "if he really wants someone to share the rooms andthe expense, I am the very man for him. I should prefer having a partnerto being alone."

Young Stamford looked rather strangely at me over his wine-glass. "Youdon't know Sherlock Holmes yet," he said; "perhaps you would not carefor him as a constant companion."

"Why, what is there against him?"

"Oh, I didn't say there was anything against him. He is a little queerin his ideas--an enthusiast in some branches of science. As far as Iknow he is a decent fellow enough."

"A medical student, I suppose?" said I.

"No--I have no idea what he intends to go in for. I believe he is wellup in anatomy, and he is a first-class chemist; but, as far as I know,he has never taken out any systematic medical classes. His studies arevery desultory and eccentric, but he has amassed a lot of out-of-the wayknowledge which would astonish his professors."

"Did you never ask him what he was going in for?" I asked.

"No; he is not a man that it is easy to draw out, though he can becommunicative enough when the fancy seizes him."

"I should like to meet him," I said. "If I am to lodge with anyone, Ishould prefer a man of studious and quiet habits. I am not strongenough yet to stand much noise or excitement. I had enough of both inAfghanistan to last me for the remainder of my natural existence. Howcould I meet this friend of yours?"

"He is sure to be at the laboratory," returned my companion. "He eitheravoids the place for weeks, or else he works there from morning tonight. If you like, we shall drive round together after luncheon."

"Certainly," I answered, and the conversation drifted away into otherchannels.

As we made our way to the hospital after leaving the Holborn, Stamfordgave me a few more particulars about the gentleman whom I proposed totake as a fellow-lodger.

"You mustn't blame me if you don't get on with him," he said; "I knownothing more of him than I have learned from meeting him occasionally inthe laboratory. You proposed this arrangement, so you must not hold meresponsible."

"If we don't get on it will be easy to part company," I answered. "Itseems to me, Stamford," I added, looking hard at my companion, "that youhave some reason for washing your hands of the matter. Is this fellow'stemper so formidable, or what is it? Don't be mealy-mouthed about it."

"It is not easy to express the inexpressible," he answered with a laugh."Holmes is a little too scientific for my tastes--it approaches tocold-bloodedness. I could imagine his giving a friend a little pinch ofthe latest vegetable alkaloid, not out of malevolence, you understand,but simply out of a spirit of inquiry in order to have an accurate ideaof the effects. To do him justice, I think that he would take it himselfwith the same readiness. He appears to have a passion for definite andexact knowledge."

"Very right too."

"Yes, but it may be pushed to excess. When it comes to beating thesubjects in the dissecting-rooms with a stick, it is certainly takingrather a bizarre shape."

"Beating the subjects!"

"Yes, to verify how far bruises may be produced after death. I saw himat it with my own eyes."

"And yet you say he is not a medical student?"

"No. Heaven knows what the objects of his studies are. But here weare, and you must form your own impressions about him." As he spoke, weturned down

a narrow lane and passed through a small side-door, whichopened into a wing of the great hospital. It was familiar ground to me,and I needed no guiding as we ascended the bleak stone staircase andmade our way down the long corridor with its vista of whitewashedwall and dun-coloured doors. Near the further end a low arched passagebranched away from it and led to the chemical laboratory.

This was a lofty chamber, lined and littered with countless bottles.Broad, low tables were scattered about, which bristled with retorts,test-tubes, and little Bunsen lamps, with their blue flickering flames.There was only one student in the room, who was bending over a distanttable absorbed in his work. At the sound of our steps he glanced roundand sprang to his feet with a cry of pleasure. "I've found it! I'vefound it," he shouted to my companion, running towards us with atest-tube in his hand. "I have found a re-agent which is precipitatedby hoemoglobin, [4] and by nothing else." Had he discovered a gold mine,greater delight could not have shone upon his features.

"Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes," said Stamford, introducing us.

"How are you?" he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strengthfor which I should hardly have given him credit. "You have been inAfghanistan, I perceive."

"How on earth did you know that?" I asked in astonishment.

"Never mind," said he, chuckling to himself. "The question now is abouthoemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery ofmine?"

"It is interesting, chemically, no doubt," I answered, "butpractically----"

"Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years.Don't you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Comeover here now!" He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, anddrew me over to the table at which he had been working. "Let us havesome fresh blood," he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, anddrawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. "Now, Iadd this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive thatthe resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportionof blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however,that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction." As hespoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then addedsome drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed adull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottomof the glass jar.

"Ha! ha!" he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as achild with a new toy. "What do you think of that?"

"It seems to be a very delicate test," I remarked.

"Beautiful! beautiful! The old Guiacum test was very clumsy anduncertain. So is the microscopic examination for blood corpuscles. Thelatter is valueless if the stains are a few hours old. Now, this appearsto act as well whether the blood is old or new. Had this test beeninvented, there are hundreds of men now walking the earth who would longago have paid the penalty of their crimes."

"Indeed!" I murmured.

"Criminal cases are continually hinging upon that one point. A man issuspected of a crime months perhaps after it has been committed. Hislinen or clothes are examined, and brownish stains discovered upon them.Are they blood stains, or mud stains, or rust stains, or fruit stains,or what are they? That is a question which has puzzled many an expert,and why? Because there was no reliable test. Now we have the SherlockHolmes' test, and there will no longer be any difficulty."

His eyes fairly glittered as he spoke, and he put his hand over hisheart and bowed as if to some applauding crowd conjured up by hisimagination.

"You are to be congratulated," I remarked, considerably surprised at hisenthusiasm.

"There was the case of Von Bischoff at Frankfort last year. He wouldcertainly have been hung had this test been in existence. Then there wasMason of Bradford, and the notorious Muller, and Lefevre of Montpellier,and Samson of New Orleans. I could name a score of cases in which itwould have been decisive."

"You seem to be a walking calendar of crime," said Stamford with alaugh. "You might start a paper on those lines. Call it the 'Police Newsof the Past.'"

"Very interesting reading it might be made, too," remarked SherlockHolmes, sticking a small piece of plaster over the prick on his finger."I have to be careful," he continued, turning to me with a smile, "for Idabble with poisons a good deal." He held out his hand as he spoke, andI noticed that it was all mottled over with similar pieces of plaster,and discoloured with strong acids.

"We came here on business," said Stamford, sitting down on a highthree-legged stool, and pushing another one in my direction withhis foot. "My friend here wants to take diggings, and as you werecomplaining that you could get no one to go halves with you, I thoughtthat I had better bring you together."

Sherlock Holmes seemed delighted at the idea of sharing his rooms withme. "I have my eye on a suite in Baker Street," he said, "which wouldsuit us down to the ground. You don't mind the smell of strong tobacco,I hope?"

"I always smoke 'ship's' myself," I answered.

"That's good enough. I generally have chemicals about, and occasionallydo experiments. Would that annoy you?"

"By no means."

"Let me see--what are my other shortcomings. I get in the dumps attimes, and don't open my mouth for days on end. You must not think I amsulky when I do that. Just let me alone, and I'll soon be right. Whathave you to confess now? It's just as well for two fellows to know theworst of one another before they begin to live together."

I laughed at this cross-examination. "I keep a bull pup," I said, "andI object to rows because my nerves are shaken, and I get up at all sortsof ungodly hours, and I am extremely lazy. I have another set of viceswhen I'm well, but those are the principal ones at present."

"Do you include violin-playing in your category of rows?" he asked,anxiously.

"It depends on the player," I answered. "A well-played violin is a treatfor the gods--a badly-played one----"

"Oh, that's all right," he cried, with a merry laugh. "I think we mayconsider the thing as settled--that is, if the rooms are agreeable toyou."

"When shall we see them?"

"Call for me here at noon to-morrow, and we'll go together and settleeverything," he answered.

"All right--noon exactly," said I, shaking his hand.

We left him working among his chemicals, and we walked together towardsmy hotel.

"By the way," I asked suddenly, stopping and turning upon Stamford, "howthe deuce did he know that I had come from Afghanistan?"

My companion smiled an enigmatical smile. "That's just his littlepeculiarity," he said. "A good many people have wanted to know how hefinds things out."

"Oh! a mystery is it?" I cried, rubbing my hands. "This is very piquant.I am much obliged to you for bringing us together. 'The proper study ofmankind is man,' you know."

"You must study him, then," Stamford said, as he bade me good-bye."You'll find him a knotty problem, though. I'll wager he learns moreabout you than you about him. Good-bye."

"Good-bye," I answered, and strolled on to my hotel, considerablyinterested in my new acquaintance.