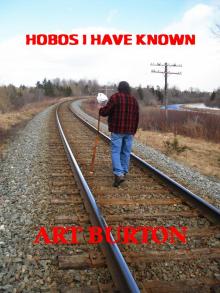

Hobos I Have Known

Art Burton

Hobos I Have Known

By Art Burton

Copyright 2011 Art Burton

License Notes

Table of Contents

THE FIRST TIME

NO ONE TURNED AWAY

SANDY, MY PROTECTOR

NEW BOOTS

THE WALKING SUITCASE

THE TEA DRINKER

WILLING TO WORK

SOCKS OR FOOD?

THE QUARTER

Closing Notes

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, central Nova Scotia became the highway for many hobos coming from the rest of Canada in search of work. Most traveled without the encumbrance of money in their pockets. To eat, they relied on the generosity of the local people to feed them. These are some of their stories.

The elements of truth that inspired most of these adventures were passed down to me from my Mother and Father, both of whom survived the Great Depression and met and fed the real life hobos who passed through the area in the thirties.

My mother, with just the slightest bit of encouragement, never tired of telling these stories. Indeed, I heard some of them so often that I truly felt these were Hobos I had known. All the stories are told in a first person, female voice.

Other ideas came from readers like you who have their own recollections of the time. Each story represents one of these remembrances which I then embellished to a length which qualifies as a short story.

Although these stories are fictional, there is a kernel of truth in each one. Nothing happened exactly as described. Literary license has been liberally applied.

All the characters are my own. Any resemblance to any person, living or dead, is strictly coincidental.

In memory of Jean and

Raymond Burton

THE FIRST TIME

You never forget the first time.

This is true of a lot of things in life. It was early spring of '30 when the first knock came to our door just after sunrise. The dew still lay heavy on the grass making the color seem more white than green. The birds were establishing their territory for the day with a barrage of twittering and chirping. The milk train had passed through about ten minutes before. As always, I used its shrill whistle as my alarm. If I wasn’t making bread, preparing breakfast for the men folk was my first chore of the day. They were already hard at work in the barn. This was usually my quiet time.

I had no concern about opening the door, even at this early hour. It was just habit. A knock, you answered. There, standing before me, were four strange men of indeterminate age but if I had to guess I would place them all in their mid-to-late thirties. My eyes opened wide and I stepped back a short pace. This was totally unexpected.

"My friend here is sick," one of them said. "Could you spare just a little bit of food for him?" He hesitated before going on. "And perhaps a slice of bread for the rest of us?" His voice faded as he made his request.

Two of the others nodded their heads in unison. They clutched their hats in front of them, removed as a sign of respect. The remaining man, sallow cheeks, dark sweaty hair and thin as a rake didn't even look up at me. It was as if lifting his head was more than he could manage.

My gaze shifted from the men to the barn at the other side of the yard. My father and two of my brothers, both older, were still there finishing up their morning chores. It would be another fifteen minutes before they returned. The other two brothers weren't home, but I don't remember where they were. My mother had passed on. I was alone.

Never had people, strangers, shown up at our door begging for food. I was at a loss about what to do at first. Who were these men? Like everyone, I had heard about the big stock market crash the previous October. It was supposed to have devastated the economy. Hundreds had lost their jobs we were told. Factory gates were locked. Nothing had changed in our lives here on the farm. The King’s coin had never been plentiful, almost nonexistent. We hardly noticed any difference between this spring and any other in recent memory.

Our cows faithfully provided us with milk everyday, both to drink and to make butter for our bread. We took turns doing the churning. The hens had their laying rotation and eggs were plentiful. Young roosters had only one purpose if they were not the cock of the walk. There was still enough bacon hanging in the smoke house to see us through until we slaughtered another pig. The root cellar was getting low, but not so low as to be a worry. Soon the new crops would be planted from the seeds gathered last fall and from the seed potatoes already starting to sprout. If this was the start of the Great Depression, like all things, we country folk were slow jumping on the band wagon. When you had little in the way of material goods to start with, you hardly noticed when they went missing.

I looked back at the men in front of me. These people represented what was to become our image of the Great Depression – hobos, or bos as they would soon be known. Although days away from escaping my teen years, I turned 20 the following week, these four men did not scare me. I detected no threat. I was alone in the house and perhaps naive. I made a decision.

"Come on in," I said. It seemed the natural thing to do when people came to your door.

They looked down, avoiding eye contact.

"If we could just have some food. Our friend hasn't eaten in three days."

Were they more intimidated of me than I was of them? Me, 5'3.

"I'll not feed you on the step," I said. "Come in."

The men were reasonably well dressed. There clothes showed no holes. Closer examination revealed the build up of dirt at the collars and cuffs. The pants bagged at the knees and the smell of dried sweat could be detected. Their shoes, although scuffed, matched. Everything seemed to fit, if a little loosely. Over the ensuing months, we would watch this standard deteriorate. The clothes would get dirtier, the smell stronger, the holes bigger.

One man wore a battle dress jacket of the Canadian Army. A uniform item my uncles wore for Remembrance Day celebrations every November. Stripes decorated both of his arms–three up, two down, a staff sergeant.

"Were you in the Great War?" I asked.

He looked at me with hollow eyes. "We fought for freedom." For a brief second I thought he would spit on the floor. "Things here are far worse than they ever were in Germany." He shook his head in a slow back and forth motion. In an almost inaudible voice I could hear: "This is winning?" Then he fell silent.

For some reason, this emotional honesty made me think I had made the right decision.

I brought some eggs, bread and jam from the pantry, sliced the bread and put it on the table, broke the eggs into a large frying pan–two each.

"Please, save some for the others," one said.

"Others?" I was confused. I looked towards the door. "What others?"

The men exchanged silent glances. "You'll see."

Even as they admonished me to be less generous in my portions, they hunched over their plates. Each had a protective arm ringing the outer edge. With the supplied fork, they shoveled the food into their mouths. Hardly chewed, washed down with gulps of hot tea. Swallowed whole and fast as if they feared I might try to retrieve it. That could cost you a finger, I thought.

Seeing men forcing their food down like this sent a shiver through me. Such hunger was foreign to our farm. To me, it was disconcerting. Meals were supposed to be a relaxing time, a time to plan the day ahead or to catch up on the day's events. The food was just there. These men forever changed that view.

In time, I met "the others" they referred to – a steady stream of them over the years. But these were the first and I will never forget them.