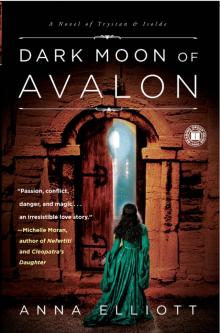

Dark Moon of Avalon

Anna Elliott

ALSO BY ANNA ELLIOTT

Twilight of Avalon

Touchstone

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2010 by Anna Grube

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Touchstone Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Touchstone trade paperback edition September 2010

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Elliott, Anna.

Dark moon of Avalon : a novel of Trystan and Isolde / by Anna Elliott.

p. cm.

1. Iseult (Legendary character)—Fiction. 2. Tristan (Legendary

character)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.L443D37 2011

813'.6—dc22

2009049279

ISBN 978-1-4165-8990-7

ISBN 978-1-4391-6456-3 (ebook)

To Nathan

Dramatis Personae

Dead Before the Story Begins

Arthur, High King of Britain, father of Modred, brother of Morgan; killed in the battle of Camlann

Constantine, Arthur’s heir as Britain’s High King, first husband to Isolde

Gwynefar, Arthur’s wife; betrayed Arthur to become Modred’s Queen; mother to Isolde

Modred, Arthur’s traitor son and Isolde’s father; killed in fighting Arthur at Camlann

Morgan, mother to Modred, believed by many to be a sorceress

Myrddin, Arthur’s chief druid and bard

Rulers of Britain

Cynlas, King of Rhos

Dywel, King of Logres

Isolde, daughter of Modred and Gwynefar, Constantine’s High Queen, Lady of Camelerd

Madoc, King of Gwynned and Britain’s High King

Marche, King of Cornwall, now a traitor allied with the Saxon King Octa of Kent

Saxon Rulers

Cerdic, King of Wessex

Octa, King of Kent

Others

Fidach, leader of an outlaw band of mercenaries

Eurig, Piye, and Daka, three of Fidach’s men, friends to Trystan

Goram, an Irish king

Hereric, a Saxon and friend to Trystan

Kian, a former outlaw and friend to Trystan, now one of King Madoc’s war band

Nest, cousin and former chatelaine to King Marche

Marcia, Nest’s serving maid

Mother Berthildis, abbess of the Abbey of Saint Joseph

Taliesin, brother to King Dywel of Logres, a bard

Trystan, a Saxon mercenary and outlaw, son of King Marche

Isolde’s Britain

Prologue

I have been a tear in the air,

I have been the dullest of stars.

I have been a course, I have been an eagle.

I have been a coracle in the seas.

LITTLE MORE THAN THE WORDS remain, now, of the wisdom of the Old Ones. A wisdom that once allowed men to read the future in the flight of birds or walk unharmed across a bed of burning coals. All that remains of Avalon, now no place in this world, but only a name in a harper’s tale. A faint, mist-shrouded echo of what once was Britain’s most sacred ground. Hidden like the Otherworld behind a veil of glass.

Once the gods of Britain ruled this land. Cernunnos, the horned god of the forests, father of all life. And his consort, the great mother goddess, known by many names: Arianhod, mistress of stars, mistress of the silver wheel. Donn, goddess of sea and air. Morrigan, mistress of night. Of battle, of prophesy, of magic and revenge.

Some say it is from her that I take my name. Morgan.

Men have given me many names besides, in my time. Sorceress …witch …whore.

And now I stand at a cliff’s edge, looking across the battle that will soon be fought to my own end.

Camlann, the battle will be called. The last bloody fight between Arthur, High King of Britain, and Modred, his traitor heir. Between Arthur, my brother, and Modred, my son as well as Arthur’s own. All because Modred seized the throne of Britain, and with it Arthur’s wife Gwynefar.

Or is it because I myself could not let go of a hurt years old? Though I kept my word to Arthur and never named him the father of my child. That was the price I paid to have Modred raised as Arthur’s heir: allowing Morgan, as much the daughter of Uther the Pendragon as Arthur is son, to be branded harlot, slut, devil’s mistress.

I never spoke aloud the ugly truth of how Arthur’s son was forced on me, in drunken violence after a battle fought and won.

Never spoke it aloud to any, at least, except my own son. If I had not—

Too late now for such questions. Too late to alter the course of any of our lives.

But it would be good, as I look down at the raven-dark head of my son’s only daughter, to believe that the power of Britain’s gods was not broken, when Roman sandals first trampled Britain’s soil. When the legions in their silver fish-scale armor defiled the druids’ sacred groves, fouled the sacred pools, and built their straight roads and marble temples like scars on the land.

It would be good, on this eve of battle, to believe that the voice of the goddess and her consort the horned one can still be heard, like the silent echo after thunder.

A gift of those same gods, I have always thought the Sight. The power to hear the voice of all living things. To catch glimpses of may be or will be in scrying waters like those before me now.

Again and again, those waters have shown me the battle to come on the fields of Camlann. And once I cared for nothing else. Nothing but the fight that would witness Arthur’s final downfall.

But now I see beyond the battle a shadow of blackness rising across Britain like the dark of the moon.

And my own end will not be slow to follow. I have seen the signs. A vision of a woman, death-pale and clad in white, who crouches at a fast-moving river and washes a bloodied gown I know is mine. A great black hound that stands by my bed at night and watches me with red and glowing eyes.

I do not fear my own death. Indeed, I would welcome it at times. But now, as I look from the scrying waters to the girl at my side, I am afraid. Coldly afraid. No use in denying it now.

My granddaughter. Daughter of Modred and Gwynefar. Isolde, her name is. Beautiful one in the old tongue. And she is beautiful. Frighteningly so, even at twelve. White skin with the luminous gleam of the moon. Delicate, finely shaped features. Softly curling black hair and widely spaced gray eyes. A shining girl, beautiful indeed.

Her face is grave, composed as she binds up a cut across the palm of her hand. A cut I made, payment in blood for the power to keep her safe in the midst of rising dark.

But at this moment I would give a hundred times that payment in my own blood to know that the charm of protection would do any good at all.

My gaze turns to the scrying bowl, with its chased pattern of serpents. Dragons of eternity, forever swallowing their tails. And slowly, slowly, an image appears on the water’s surface. Wavering, swirling, shivering, then growing steadily clear. A boy’s face, though already it holds the promise of the man he will be in a short year or two’s time. A lean, handsome face, with a determined jaw and steady, intensely blue eyes set under slanted gold-brown brows. A good face. I see no cruelty in him. And that is far rarer than one might suppose.

I had not meant to let Isolde see the vision the scrying waters have granted me this time. But before the image has faded, she looks up from the bandage she has tied across her hand—a neat job, I have taught her well—and catches sight of the boy’s face. I can see her gaze take in the shadow at the back of his blue eyes, the grim-set line of his flexible mouth.

She doesn’t question why the boy’s face should appear, now, where shadows of Arthur and Modred and Gwynefar have gone before, but only nods. “That’s very like him. He almost never smiles.”

Neither might she, were her father Marche of Cornwall. Neither might I.

Marche of Cornwall, who will soon betray my son and lose for him the battle at Camlann. At least I need not bear the guilt of my son’s death and Britain’s downfall entirely alone.

I feel sympathy for few in this life, where so many bemoan sorrows wrought entirely by their own hands. But this boy, son of Marche, does stir me to compassion. Sadness, even. Though he would scarcely be glad to know it. He has pride, I think, as well as strength of character and reserve beyond his years.

But I have guessed at the bruises he has carried beneath his clothes—marks of his father’s fists—from the time he numbered less than half of his now fifteen summers. I know he tries to protect his mother from Marche’s anger, as much as he can. Though his mother is far too much of a broken, empty shell to notice much or to care.

Still, compassion or no, I answer in a voice entirely unlike my own. As though I were suddenly one of the foolish girls who come and beg love potions from me before lying with their young men in the woods at Beltane. Age must be making me soft, indeed.

“It’s because he has no one in his life to love him,” I hear myself tell the girl at my side.

“I do.” Her face is so serious, her gray eyes very grave, though she can scarcely be old enough to understand the meaning of what she says. Not even old enough for the words to make her afraid. “I will.”

Book I

Chapter One

WHEN SHE’D LET HERSELF BE led to the great carved oaken bed, they left her, though she knew they would wait outside the door. Marche would have made sure of his witnesses.

She dug her nails hard into the palms of her hands. It’s only my body, she thought. I won’t let him touch the rest of me.

She slipped her hand under the mattress. The cloth-wrapped parcel was where she’d left it the night before, and she drew it out, untying the strings that held it closed then drawing out a woolen ball, smeared with the cedar and mandrake paste. If Marche discovered it, she would be dead, as surely as she lay here now. But if she conceived a child—Marche’s child—

She thought, suddenly, of Con. Of what Con would think if he knew she was about to give herself to another man. And not just any man. Marche. The traitor who had caused Con’s death.

She thought for a moment she was going to vomit, but she fought the sickness down, whispering the words through clenched teeth.

“You can face this. You have to.”

Her hands were unsteady, but she reached down and thrust the paste-smeared ball deep inside her. In the darkness beyond the bed, she heard a door open—

ISOLDE CAME AWAKE WITH A JOLT and lay a moment, her heart pounding, her breath painful in a throat that felt swollen and dry. She pressed her hands to her temples, drawing a shuddering breath, and gradually the dream retreated, the frantic beating of her heart slowed. Though since it had not been a dream—or rather not only a dream—she had to close her eyes and count one hundred, shivering as the sweat dried on her skin, before she could force herself to move.

Five months. Five months nearly to the day, since she’d given Con’s murderer her marriage vow and escaped from him the next day. Three months since the king’s council had declared her marriage to Marche of Cornwall void, on the grounds of Marche’s treason. And by now, she could almost put it behind her and keep the yawning jaws of memory at bay. Until the dream came again, and she was flung back into that night, feeling its echo in her very bones. Feeling soiled, slimy all over, and as though she could scrub and scrub until her skin was bleeding raw and still never be clean again.

Isolde opened her eyes. It was nearly dawn; a faint, pearly light crept in through the room’s single narrow window, showing the clean rushes and herbs scattered on the floor, the heavy carved furniture and tapestried walls. She’d fallen asleep on the wooden settle beside the hearth; her limbs felt cramped, and the muscles of her back and neck were aching and stiff.

Isolde drew another steadying breath, then forced herself to rise, to go to the window, unfasten the shutter, and look out, breathing the damp, earth-scented spring air that came at her in a rush.

The great hill fortress at Dinas Emrys was an eerie place, always, surrounded beyond the outer wooden palisade by mists and silence and gnarled trees growing on rocky mountain ground. Now, though, with the gray dawn breaking over the eastern hills, and with a soft, penetrating spring rain breathing tattered gray patches of fog over the canopied trees, the mountain fort felt apart, outside the world beyond the hills. Outside even of time, a space somewhere between truth and tale.

Beneath this mountain and a man’s lifetime ago, so the bards’ songs and fire tales ran, Myrddin the Enchanter had unearthed a sacred pool and there been granted a vision of a pair of warring dragons, one white and one red. And on their final desperate battle, Myrddin had prophesied the triumph of the red dragon banner of Britain’s armies over the invading Saxon foe.

Though that, Isolde thought, was the kind of story folk clung to in times such as these—like the stories of Arthur, king who was and shall be. Who had not died at Camlann with all the rest of Britain’s hope, but instead slept amidst the chimes of silver apples on the Isle of Avalon and would come again in the hour of his country’s greatest need.

She had a sudden, piercingly sharp memory of Con, asking Myrddin once if the tale of the warring dragons were true. Con had been—what? Fourteen, she thought. Fourteen, and already Britain’s High King for two long years—just days before returned from facing his first battle with a deep sword cut in his side.

Isolde could see him, even now, as he’d lain in the king’s tapestried bed, restless, because he hated at all times to be still, his face tight with the pain he wouldn’t admit to, and his dark eyes still lost in the memory of all he’d seen and done. Isolde had stitched the wound and sat by him at night, waking him when he relived the blood and killing in nightmares and cried out in his sleep—as all men did after battle, for a time. She’d been fifteen herself then—nearly five years ago, now—and wedded to Con the two years since he’d been crowned.

Myrddin had stood at Con’s bedside in the bull’s-hide cloak of the druid born, a raven feather braided into his snow-white hair, and Isolde had seen in his eyes a reflection of the pain in Con’s. Though his voice, when he spoke to answer Con’s question, was dry.

“Dragons? Oh, to be sure. I keep a pair at home for use in the kitchens roasting haunches of game.”

And then, when Con moved impatiently and started to speak, Myrddin held up a hand, and said, his face suddenly grave, “You wish to hear what I know of dragons? Very well.” His voice held suddenly the lilt of a harper’s song—or of prophecy. A faint, musical echo that made his words seem to hang shimmering in the air a moment after he’d done. “Dragons doing battle I have never seen, either i

n vision or in life. But I did once, many years ago, see a pair of the creatures—a she-dragon and a male—engaged in their mating dance.” He shook his head, fingering the strand of serpent bones he wore at his belt. “You’ll have heard, I suppose, how it is dragons mate?”

Con was lying back on the pillow, eyes closed against a fresh spasm of pain and a sheen of sweat on his brow, and shook his head without much interest, his jaw clenched tight.

“Very carefully.” Myrddin’s lilting voice was still tranquil, his sea blue eyes grave. “All those spines and breaths of fire, you understand.”

Con had laughed so hard he’d torn out half his stitches, and Isolde had had to put them in again. And he’d slept without dreaming for the first time that night. Though always, after that, the sadness in Myrddin’s eyes when he looked at Con was never quite gone.

Now, seeing again Con’s laughing face—and Myrddin’s high-browed, ugly one, gentle with reflected pain—Isolde felt a hot press of tears in her eyes. Five months, too, that both of them had been gone. But then, she thought, that was the nature of grief. She’d learned that, these last seven years. One moment you thought the pain was finally—finally—beginning to wear smooth at the edges with the passage of time. And then the next you were crying like the loss was still only hours old.

At least, though, the months since Myrddin and Con had died at Marches’ hands made it easier to set grief aside in the face of what now had to be done. Isolde blinked the tears back, scanning the spread of hills beyond the palisade walls.

But there was nothing to be seen besides the sweep of trees and rocky hills and mist. No ominous column of greasy black smoke above the tree line. And no sign of alarm, either, in the fortress’s outer courtyard beneath Isolde’s window.

Though that, she thought, only meant that last night’s attack hadn’t occurred anywhere nearby.

Slowly, she turned to the washbasin and earthenware jug of water that stood by the hearth, where the heat of the fire would keep it from freezing in the nights that were still frostbitten and bitterly cold. Too great a risk, now, to keep Morgan’s scrying bowl, with its ancient chasings and serpents of eternity etched on the age-smoothed bronze sides.