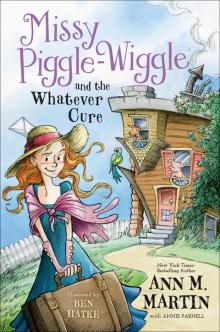

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure

Ann M. Martin

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Authors and Illustrator

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Feiwel and Friends ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Ann M. Martin, click here.

For email updates on Annie Parnell, click here.

For email updates on Ben Hatke, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Based on the Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle series of books and characters created by Betty MacDonald and Anne MacDonald Canham

For Betty MacDonald, and the magic she brought to my childhood and to generations of readers

—A. M. M.

For Will and Elsie, who taught me that we all need a cure every now and then, even though we’re perfect

—A. P.

Dear Missy,

As you know, my husband, Mr. Piggle-Wiggle, was called away some years ago by the pirates. After waiting so long for him to return, I have decided to take matters into my own hands and find out what happened to him. I’ll be leaving tomorrow. While I’m gone, could you stay at the farm and live in the upside-down house? I’m sorry to ask you to leave your home and your work, but I need you. Harold Spectacle will take care of the animals until you arrive in Little Spring Valley.

I’m sure you remember what to do for Wag, Lightfoot, Lester, and the others. Everything at the upside-down house is just as it was the last time you were here.

I apologize for the haste with which I’m making these preparations. Some things can’t be helped.

Please come as quickly as you can.

Sending you love,

Auntie

1

Missy Piggle-Wiggle

THE MOST WONDERFUL thing about the town of Little Spring Valley was not its magic shop, and not the fact that one day a hot-air balloon had appeared as if from nowhere and floated over the town and no one ever knew where it had come from, and not even the fact that the children could play outside and run all up and down the streets willy-nilly without their parents hovering over them. No, the most wonderful thing about the town was the upside-down house, and of course the little woman who lived in it.

The upside-down house had been built for Missy’s great-aunt, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, by her husband, Mr. Piggle-Wiggle the pirate. It was the house Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle had dreamed of when she was a little girl, with ceilings for floors and floors for ceilings and light fixtures growing up beneath your feet that must be stepped around as you tromp through the house. Missy had looked forward to her childhood visits to the upside-down house and the little lady who was known for her great understanding of children. She had been allowed to visit without her mother, who had no patience for a house standing on its head, not to mention her aunt’s fondness for magic. Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, whom Missy called Auntie, had thought up playing Cinderella as a way of getting the beds made, and garbage races as a way of taking the trash cans to the street on garbage-collection day, and pirate parties as a way to clean house, with a great deal of heave-ho-ing and the tossing out of dirty dishwater accompanied by a cry of “Man overboard!”

Since Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle was indeed magic, she kept a cupboard stocked with potions and powders and vapory things meant to cure children of any number of bad habits. Missy’s mother was disdainful of these cures, which is a polite way of saying that she mocked and scorned them. The grown-ups in Little Spring Valley, however, were very grateful to Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle for her help with their children’s selfishness and tiny-bite eating and bath avoidance.

Living with Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle were Wag the dog, Lightfoot the cat, Penelope the talking parrot, and Lester the pig, who didn’t talk but who had exquisite manners and also liked to drink four or five cups of coffee at every meal. The yard around the upside-down house was where Mr. Piggle-Wiggle had buried his pirate treasure, and when Missy was a little girl and not busy practicing magic of her own, she had spent many hours digging for gold. The children of the town did the same thing now, so the yard was always full of holes, which Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle didn’t care about one bit as long as the children eventually planted flowers in the holes.

Missy Piggle-Wiggle arrived in Little Spring Valley on a warm morning exactly three days after she had received the letter from her great-aunt, and exactly two days after she had reluctantly left her new post at the Magic Institute for Children. She’d stuck the letter in the band of her straw hat, and now she plucked it out and read it again as she approached the upside-down house. The letter had been written in haste, and she wondered why. She also wondered why Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle had suddenly decided to search for her husband. Where did one look for pirates, anyway? Furthermore, who was Harold Spectacle?

The sun shone on Missy as she returned the letter to her hat and made her way down the street again. A hummingbird buzzed by on its way to a pot of petunias. On the front porch of a tidy yellow house, a sleeping cat woke up suddenly, leaped at a fly, and went back to its bed. Missy switched her suitcase from one hand to the other. She shaded her eyes and said aloud, “Ah. There it is.”

Ahead of her was a small brown house with its bottom sticking up into the sky and the roof poking into the ground. Missy was at once confronted by two feelings that seemed to have very little to do with each other. She felt happy longing for the childhood days she had spent with Auntie, learning about the potions and practicing her own magic (she was a quick learner, not afraid to make mistakes, no matter how many things accidentally levitated or disappeared), and she felt an anxious prickling around her ears and behind her eyes as she recalled that the upside-down house could sometimes behave like a rude and obstinate child. It loved Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle. It also had an excellent memory for Missy’s childhood mishaps and had never recovered from the unfortunate afternoon when she had unintentionally converted the upside-down house to a right-side-up house. Missy had reversed the magic in a matter of seconds, but the house didn’t forgive her until she had apologized 671 times.

Missy hesitated at the end of the walk that led to the front door. The door was located in the peak formed by the roof. There were two knobs on it, one high up where you’d find a knob if you turned a door upside down and a reachable one closer to the ground.

“I’m coming, House,” she whispered. She shaded her eyes and thought she could see figures in the windows. Lester’s snout and Penelope’s beak, Wag and Lightfoot standing on their hind legs with their paws against the panes of glass. Missy set one foot on the path.

The stone tilted to the left, and Missy clutched at her suitcase. “I’m still coming,” she called. “Can’t you forgive me, House? I’m really sorry. There. That’s my six hundred and seventy-second apology.”

The second stone sank into the ground as if Missy had stepped on a lily pad in a pond. She let out a sigh but bravely heaved herself out of the hole and marched toward the door, wobbling and weaving as the path shifted beneath her.

When she reached the front steps, she dropped her suitcase smartly on the wooden boards. “Auntie asked me to come here,” she told the house. “She needs my help and … that’s that!”

The envelope enclosing the letter to

Missy from her great-aunt had also held a key to the house. Missy now withdrew the key from her purse. She stuck it in the lower doorknob. The knob let out a scream, and Missy drew the key back with a smile. “Very funny, House,” she said. “You know you’re going to have to let me in sooner or later.”

She inserted the key in the lock a second time and heard nothing. She turned the key. The knob disappeared.

“Don’t you dare!” exclaimed Missy. She waited twenty seconds for the knob to reappear (which is a long time if you’re doing nothing but standing and staring and waiting). “All right,” said Missy at last. “Two can play at this game.” She flicked her hand, the door hinges unfastened themselves, the door fell forward into the hallway, and Missy plucked up her suitcase and stepped inside.

Slowly the knob reappeared, the key still in the lock.

“Thank you,” said Missy. She flicked her wrist again. The door bumped itself upright, and the pins slid back into the hinges. “I certainly hope we’re not going to have to go through that every time I want to get inside.”

She heard faint laughter from the walls of the house.

In the dim light, Missy could now see Wag, Lightfoot, Penelope, and Lester standing in a row in the foyer. Wag was wagging his tail, which, of course, was why he had been named Wag in the first place, and his mouth was hanging open, which might have been because of the crashing door or might simply have been because he was a dog. Lightfoot was standing with her back to Missy, her tail twitching dangerously. Penelope was staring, unblinking, her head cocked to one side. Lester attempted to recover from his surprise. He put a smile on his face and stuck out his right front hoof. Missy shook it.

“Lightfoot,” said Missy, “is something wrong? Did I scare you? I’m sorry if I did.”

The cat threw a reproachful glance over her shoulder and slunk away.

“A bad time is what it is,” squawked Penelope. “A bad time. A bad time.”

Missy turned to Wag and put her arms around his neck. “I’m glad to see you,” she murmured.

Wag wagged his tail again and licked her ear.

“Well,” said Missy smartly as she straightened up. “There’s nothing to do but get right to work and set things in order. Let’s get organized.”

“Time to feed us. That’s what Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle would do,” said Penelope, flapping her wings. “Feed us.”

“It isn’t your dinnertime and you know it,” said Missy.

“Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle would give us a snack.”

“Would she? Well, we’ll see. Now. I know Auntie must have left me—ah, here it is.” Missy caught sight of an envelope on a table by the doorway. She reached for it, and the envelope was whisked into the air. “House! Return that, please!”

The envelope floated to the floor. Missy picked it up, slit it open, and drew out a single sheet of paper. She stepped over a doorway and carried the paper into the parlor, where she sat on a great fluffy chair next to a dollhouse that one of Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s many child visitors had been building out of Popsicle sticks, paper-towel tubes, and feathers.

Missy read the note aloud to Lester, who had followed her into the parlor and seated himself on a sofa with his hind legs crossed just so. She read slowly because the hastily written note was nearly impossible to decipher.

Dear Missy,

If you are reading this, then you have found your way to Little Spring Valley and the upside-down house. Thank you for coming.

The food for Wag, Lightfoot, and Penelope is in the kitchen cupboard next to the stove. You will know which is for whom because the containers are labeled. Lester eats human food from the refrigerator and will sit at the table with you because of his extreme good manners.

Here Missy glanced at Lester, who nodded and smiled at her, and then blushed slightly. Missy patted his hoof and returned to the letter.

The food for the barn animals is in the barn. Feeding instructions are tacked up on the wall by Trotsky’s stall.

I asked Harold Spectacle, who owns A to Z Books, the bookstore on Juniper Street, to come by twice a day to feed the animals. Please let him know when you arrive and thank him for helping out.

Sending love,

Auntie

PS There’s a family—

Here Missy slowed down and stopped reading altogether. “Auntie has the most atrocious handwriting,” she remarked to Lester.

Lester nodded sympathetically.

“What’s this word?” she asked, and held the note in front of him. “Can you read it?”

Lester frowned. He took the paper in his hooves and turned it around and around and around. Then he shrugged and handed the note back.

Missy stared at the scrawled words. “A family in trouble?” she murmured. “A family named Freeforall who’s having trouble with their children? I think this is their address. Do you know the Freeforalls, Lester?”

Lester nodded and looked very sad.

“Well, if there’s trouble with the children, then I must visit them. Don’t worry, Lester. I’m here to help. I’ll get things sorted out. But first things first.”

Missy picked up her suitcase. “Come with me, Wag,” she said as she approached the stairs.

Wag stood up from where he’d been sleeping under a table and shook himself.

Missy set her foot on the first step and then fell forward as the staircase vanished. “House! Put it back!” she commanded as Wag licked her face with concern.

The staircase reappeared. It was six inches tall. Missy hid a smile, but Wag growled nervously and eyed the second floor.

“Full-size!” said Missy.

The staircase grew and then slid toward the parlor, bumping against the ceiling.

“Put it back as it was and where it belongs!” ordered Missy. “Right now.”

The staircase returned to the center of the foyer. Wag looked warily at it.

“It’s okay,” said Missy. “House and I have known each other a long time.” She carried her suitcase upstairs, Wag at her heels, turned right, and walked down the hall to the room she always stayed in when she visited.

The door was closed. “House, I hope this door is unlocked,” said Missy. She reached cautiously for the knob and turned it. “Thank you,” she said.

The room was as she remembered it. A bed covered with a neat white spread, a blue quilt folded across the foot. A chest of drawers, a window framed by blue-and-white-flowered curtains, and a wooden cabinet in the corner. The cabinet was painted blue. Missy tugged at the door. It was locked.

This was not the fault of the house. The door was supposed to be locked. Missy withdrew a locket and removed a small brass key with a bit of pink ribbon tied to one end. She inserted the key into the lock. The door creaked open.

“My potions,” said Missy with satisfaction. “Just as I left them.” She took in the rows of small bottles and jars and tins, each labeled with the name of the unwanted habit it would cure. She lifted a square purple bottle from the middle shelf. “‘Won’t-Take-a-Bath Cure,’” she read. She uncorked the bottle and sniffed it. “Mmm. Grapy. Remember when I tried this on you, Wag? Wag?”

Missy caught sight of Wag’s tail disappearing around the corner as he crept into the hall. “I’m not going to do it again!” she called after him. “I was only little then. I was still learning the magic.”

But Wag was gone. Missy made short work of arranging her clothes in the bureau drawers. She lined up her shoes in the closet and placed a stack of books by her bed. She reached into her suitcase for pajamas, her toothbrush, her slippers, and her woolen cold-weather hat. At last she pulled out the satchel that she would take with her to the Freeforalls’ that afternoon.

Downstairs, Missy walked through the kitchen, where Lightfoot had jumped to the top of Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s funny old black stove and was surveying the room.

“Come with me to the barn,” Missy called to the animals as she let herself out the back door. But only Penelope followed, wings flapping as she thrust herself thro

ugh the door just before it closed.

“Could have squished me!” she called. “Ever heard of holding a door open? Could have squished me.”

“Sorry,” said Missy. “Luckily, you’re an excellent flier. Now, remind me who’s out in the barn.”

“Why, Trotsky the horse, of course; Heather the cow; and Pulitzer the owl. Warren the gander; Warren’s wife, Evelyn Goose; Martha and Millard Mallard. And the chickens and rabbits and turkeys are around somewhere. The sheep are in the pasture.”

Missy stepped through the door to the barn, which was not upside-down but a regular barn. An upside-down house was one thing, but an upside-down barn, with the stalls in the air and the hayloft on the ground, would have caused all sorts of problems, such as how to coax a horse and cow upstairs to their beds each night, and how to pitch hay up above one’s head.

Missy peered into the dim light and leaned back to look into the rafters. There perched Pulitzer, sound asleep since it was hours before his hunting time.

Missy peeked in the stalls. “Hello, Trotsky. Hello, Heather,” she said. She patted their backs. Then she led them outside and turned them into the pasture with the sheep.

There were always so many farm chores to take care of, but Missy could see that Harold Spectacle had done a good job. The troughs were filled with clean water. There was fresh straw in the stalls. The rabbit hutches and turkey pens had been scrubbed.

“Harold seems very responsible,” Missy remarked approvingly.

“Snack time! Snack time!” squawked Penelope.

Missy eyed the parrot. “I don’t remember seeing anything about snack time for the animals in Auntie’s instructions,” she replied. “But let’s go back in the house and look again.” She crossed the yard, pausing to admire Warren and Evelyn’s goslings on the way.

Penelope flapped along, and Missy remembered to hold the back door open for her. In the kitchen, Missy looked in a cupboard and found the container of parrot food.