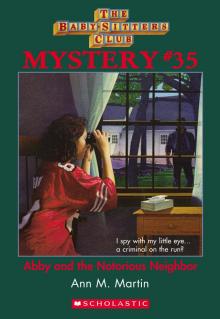

Abby and the Notorious Neighbor

Ann M. Martin

Contents

Title Page

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Acknowledgment

About the Author

Also Available

Copyright

“Ahh … ahhh … ahhh — CHOO!”

“Bless you.” My mom looked up from her newspaper. “You’ve been sneezing a lot this morning, haven’t you?”

“Twedy-dide tibes sidce I woke up,” I said, nodding. “A record eved for be.” I wiped my streaming eyes with a napkin and reached for a cinnamon roll.

“You sound awful!” said Anna, my twin sister. (Even though we’re identical, she doesn’t have any allergies. I have enough for both of us, a fact I may just have to hold against her until we’re eighty.)

“I feel biserable,” I admitted. I did, too. My nose was totally stuffed up, my head was aching, and my throat felt scratchy. Not to mention my brain, which felt as if it were wrapped in cotton. I didn’t know how I was going to make it through a whole day at school.

It was a Monday morning in early June, which meant that I wouldn’t have to worry about making it through too many more days of school. Classes were winding down, which was good. Allergy season was winding up, which was very, very bad.

My name’s Abby Stevenson, and I’m allergic to just about everything in the universe: dust, shellfish, milk, pollen, dogs. Not cats, though, believe it or not. I am, however, allergic to kitty litter. Go figure, as a New Yorker might say. I know New Yorkese because I’m originally from Long Island. I just moved here (“here” is Stoneybrook, Connecticut) recently. Anna and I are thirteen and in the eighth grade at Stoneybrook Middle School, otherwise known as SMS.

We’ve made plenty of new friends. Anna’s are mostly kids she knows from music classes, since her life pretty much revolves around her violin (she’s an awesome fiddler). Mine are either teammates (I’m kind of a jock) or members of this great club I belong to (the Baby-sitters Club, or BSC — more about that later). None of our new pals has any trouble telling my twin and me apart, even though we have identical genes. We never dress alike, for one thing, and while we both have thick, curly brown hair, I wear mine long and Anna’s is cut short, with bangs. We’re both nearsighted, though, and always wear either glasses or contacts.

That morning, I was wearing my glasses. I hadn’t worn contacts for days, since my eyes had been way too itchy. In fact, my eyes were so teary now that I had to take off my glasses to wipe them again. Then I sneezed, for the thirtieth time since I’d woken up. After the sneeze, I coughed a little. My throat was feeling scratchier by the minute.

My mother looked up again, and concern showed in her eyes. “I wish I didn’t have a late meeting today,” she said. “I don’t like the way that cough sounds.” My mom worries about me a bit, because along with the allergies I also have asthma, which, when I have attacks, leaves me gasping for air. I can usually control the asthma with my prescription inhalers. But a couple of times I’ve had really bad attacks that landed me in the ER. Scary.

“I’ll be fide,” I said. While I don’t always love the hours my mom keeps — she’s a high-powered editor at a New York publishing house — I know her job means a lot to her, and I didn’t want her to skip an important meeting. “I took by bedicide. I’ll be feelig better sood.” I coughed a little more.

“Well, at least let me make you a cup of herbal tea. It’s good for your throat,” said Mom. She stood up and headed for the stove.

“Thanks.” I reached for the newspaper. Just then, I heard a roar from outside. “Oh, do!” I moaned.

“He’s at it again,” said Anna, craning her neck to peer out the kitchen window.

“I don’t believe it,” muttered my mom. She was at the sink now, filling the teakettle with water as she glared out the window. “Why can’t he do that just a little bit later? Doesn’t he realize that some people might still be trying to sleep?” She banged the kettle down on the stove and snapped on a burner.

The roar continued. It was Mr. Finch, our backyard neighbor, mowing his lawn. I didn’t like the noise, but even more, I dreaded the newly cut grass. It never fails to make my allergies worse.

“Maybe I should talk to him,” murmured Mom. “Ask him to wait until at least nine. Especially on weekends. I mean, eight is too early on a Monday, but remember last Saturday, when he started at seven-thirty?” She stood by the window, watching.

I didn’t even look. I could picture the scene. Mr. Finch was a fastidious home owner, and he mowed his lawn at least twice a week, always early in the morning. He also clipped every stray blade of grass and weeded the walkways until the yard looked ready for a military inspection. He didn’t have any flower beds, but I imagined that if he did, the tulips would be lined up in straight rows and the roses would be pruned to within an inch of their lives.

Mr. Finch had moved into his house at about the same time we’d moved into ours. He didn’t appear to have any family living with him, nor did we ever see friends stop by to visit. Mr. Finch was not a particularly neighborly neighbor; I couldn’t imagine him dropping over for a cup of coffee or inviting us to a spontaneous backyard barbecue. No, Mr. Finch kept to himself, and I wasn’t sorry. He didn’t seem like a very friendly person.

“Don’t bother talking to him, Mom,” Anna advised. “I have a feeling Mr. Finch doesn’t care if the noise bugs us. And after all, he has to listen to me practice for hours every afternoon.”

“That’s different,” said my mother. “Your violin is hardly as noisy as his lawn mower, and the way you play, even scales sound delightful.” She turned away from the window to bring me a steaming mug of tea. “Still, you’re probably right. I have better things to do with my time. Speaking of which,” she continued, glancing at her watch, “I have a train to catch.” She picked up her cup for one last gulp of coffee, then put it down and grabbed her briefcase. “See you two around eight,” she said, giving us each a quick hug. “Try to take it easy today,” she told me seriously. “No racing around.”

“Dod’t worry,” I said glumly. I felt too tired and dragged out to even think about taking my usual five-mile run after school. That was pretty amazing, since I don’t usually let anything stand in the way of exercise. Trying to put on a brighter face to keep my mom from worrying, I took a sip of tea. “That’s good,” I said. “I feel better already.”

My mother smiled. “I hope you’ll feel a lot better by tonight.” She stroked my hair. Then she was gone.

Anna and I finished up breakfast and put our dishes in the sink, all without talking much. The roar of Mr. Finch’s mower filled the air, and I didn’t feel like shouting over it. I don’t think she did either.

I can often tell what Anna’s feeling. As twins, we have a special bond. There have even been times when I’ve had a sudden twinge, a definite sensation that something was wrong with Anna — only to find out later that she’d fallen off her bike or had a fight with a friend. The same has happened to her. And when we were little, we were so close that we had a special made-up language all our own. Nobody else could understand, but the words made perfect sense to us.

Not long ago, a doctor discovered that we both have scoliosis, which is a curvature of the spine. Mine is very slight, but Anna’s needs treatment. At first I felt so awful for her that I almost smothered her with caring

and worry. These days, she treats her scoliosis the way I treat my asthma and allergies: as a minor inconvenience that barely slows her down and definitely doesn’t keep her from enjoying life. She’s still wearing a brace, but she’s used to it and so am I.

One thing we’re not completely used to, and probably never will be, is the fact that we don’t have a dad anymore. Our father was killed in a car wreck about four years ago, and his absence has left a gaping hole in our lives. It’s pretty hard to come to terms with such a huge, sudden loss, and I don’t think any of us — Mom, Anna, or I — has completely worked through our feelings.

All I know is that I still miss my dad, every single day. I miss telling him about stuff, like the two incredible goals I made in a soccer game or about how I trimmed three seconds off my personal-best time for the hundred-yard dash. I hated that he wasn’t around to see Anna and me become Bat Mitzvahs (we’re Jewish, and a Bat Mitzvah is a celebration of a young woman’s entry into adulthood), and I miss his dumb jokes and his warm hugs and his harmonica playing and his everything.

But I also know that he’s part of me — of us — now. I’ve taken to telling dumb jokes. Anna’s learned to play the harmonica. And my mom, not a very demonstrative person before, has been working on her hugging skills.

Not long ago we even started visiting his grave, something I couldn’t face for a long time. It feels good, like a connection with him. One time I left an old pair of soccer cleats there, as a symbol of the way I was growing up and moving on.

“Thinking about Dad?” Anna’s voice broke into my thoughts.

“How did you know?” I asked, turning to face her. By then, we were both nearly ready to leave for school. I was in the front hall, stuffing my math book into my backpack. Anna was pulling a music stand out of the closet.

She shrugged. “I just did,” she said. “You had that look on your face.”

I knew exactly what she meant, because she has the same look whenever she’s thinking about our father. Looking at Anna is sometimes like looking in the mirror. I smiled at her. She reached out and patted my shoulder. Then we opened the door and stepped outside. Mr. Finch had finally finished mowing his lawn. Even from our front door I could hear the snick-snick of his clippers as he trimmed stray blades of grass. The smell of freshly cut lawn hung heavy in the still morning air.

I sneezed three times in a row.

“Thirty-wud, thirty-two, thirty-three,” I said, smiling weakly at Anna. “It’s goig to be a wodderful day.”

It wasn’t a wodderful day. It was a long, horrible slog of a day, and by the time the last bell rang at school, I was ready to sleep for a week. I felt completely and totally exhausted. It was an effort just to keep my eyes open on the bus ride home.

I didn’t even have the energy to make myself a snack. I just did the Frankenstein walk (arms outstretched, eyes half shut) to the couch, collapsed onto it, and fell into a deep sleep. And if I hadn’t woken myself up with a coughing fit, I probably could have snoozed the whole afternoon and night away right there on the couch. As it was, I woke up before either Anna or Mom arrived home, feeling as foggy as if I’d never napped. I yawned, stretched, and checked my watch. Then I sat up with a start.

It was almost five-fifteen! Any second now, a car would be honking out front: my ride to the BSC meeting, which would begin at five-thirty.

After one last lung-busting round of coughing, I stood up — a bit unsteadily — and ran a hand through my hair. I sneezed four times, blew my nose, and wiped my eyes. Then I rummaged around in my backpack and pulled out a little vial of allergy pills. I was due to take one, so I shook one out and popped it into my mouth, washing it down with a swig from the bike bottle I carry around.

“Okay, then,” I said to myself. “Ready? Ready!” It wasn’t much of a pep talk, but it was all I could manage. I was extremely tired, and I felt as spacey as a Martian.

Just then, I heard the car horn I’d expected, so I dashed out to join Kristy — that’s Kristy Thomas, president of the BSC and my neighbor — in the backseat of her brother Charlie’s car. I slammed the car door behind me and adjusted my seat belt as Charlie revved the engine. As soon as I was settled, he took off with a rattle and a roar. (His car is known as the Junk Bucket. I think that’s a nice name for it.)

I turned toward Kristy and smiled.

She gave a horrified gasp. “Ugh! Why are your eyes so red? You look awful,” she said.

“Why, thaks,” I replied. Nobody ever said I can’t take a compliment gracefully. “You look terrific, yourself.” Kristy, who has brown hair and eyes and is on the short side, was dressed in her usual “uniform” of jeans and a T-shirt.

She shrugged off my remark. “Maybe you should have stayed home,” she said. “You must be really sick.”

“It’s just allergies. I cad bake it through the meeting,” I said. I hate to miss BSC meetings. The club has been one of the best things about moving to Stoneybrook.

“You know best,” said Kristy, shrugging. I could tell she didn’t really believe I did, though. Kristy always thinks she knows best.

The funny thing is that she often does.

Kristy is president of the BSC because the club was her idea. She was the one who realized how much parents would like being able to call one number (on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, from five-thirty until six — that’s when we meet) and reach a whole group of responsible, experienced sitters. She was also the one who figured out that there should be a club record book for keeping track of our schedules and our clients’ addresses, and a club notebook for keeping track of what’s going on with our charges. She came up with the idea for Kid-Kits (boxes stuffed with markers, toys, and books that we sometimes bring to jobs on rainy days), and she was the one who realized it would be good for the club to have associate members, who don’t come to meetings but who are on standby for busy times.

By now you’re beginning to understand that Kristy is an idea person. This is true. She’s also a good leader (some people call her bossy) and a smart businessperson. You see, the BSC is more like a business than a club, and Kristy functions as its CEO (Chief Executive Officer).

How did Kristy come to be the person she is? Well, I think it’s because of her family life. For one thing, her mom’s an incredibly strong role model. She brought up four kids (Kristy, her two older brothers, and a younger brother) on her own after Kristy’s dad walked out on the family long ago.

For another thing, Kristy has had to learn to be organized, since her family is now so huge and complicated. It’s no longer just Kristy and her mom and her brothers. Kristy’s mom remarried. Her new husband is a terrific guy who happens to be a millionaire and who has two kids from an earlier marriage. After the wedding Kristy’s mom and Watson, Kristy’s new stepdad, adopted a toddler (a Vietnamese orphan). These days, their house is no less than chaotic at all times. Kristy’s grandmother lives with the family too, and there are all kinds of pets (I can’t keep count — all I know is that I’m allergic to most of them) running around. Fortunately, the house is huge, a mansion, actually.

I like Kristy, but sometimes I think we’re almost too much alike ever to be true best friends. We’re both stubborn and outspoken, and we’re both pretty athletic and competitive. Kristy’s favorite sport is softball, and I’ve been helping her coach this team she manages for very young kids. She’s great with the kids, patient and kind.

“Abby, wake up!” Kristy was nudging my shoulder. Charlie had pulled up in front of Claudia Kishi’s house, which is where the BSC meets. (Before she moved to Watson’s mansion, Kristy lived across the street from Claudia.) “We’re here.”

“I wasd’t sleepig,” I insisted. “Just studyig the idside of by eyelids.” That was one of my dad’s old jokes.

Kristy rolled her eyes. “Whatever,” she said. “Let’s go.”

We let ourselves into the house and thumped up the stairs to Claudia’s room. (Well, Kristy thumped. I dragged.) Claudia welcomed us, but I barely even said h

ello. I just did the Frankenstein thing again, heading straight for her bed. I lay down across it and shut my eyes — just for a second.

The jangling of a phone woke me up. For a moment, I had no idea where I was or what time it was or even who I was. I tried to jump up to answer the phone, but my body wouldn’t obey. Fortunately, someone else picked it up.

“Sure, Mrs. Rodowsky. Wednesday afternoon will be no problem. We’ll call you back to let you know who’s taking the job.”

That was Claudia talking. Slowly, it all came back to me. I was at a BSC meeting, and as I looked around the room I realized that all the other members had arrived. Not only that, but Kristy must have already called the meeting to order, because a glance at the clock told me it was 5:35.

Claudia turned to Mary Anne Spier, the club secretary. “Who’s free on Wednesday?” she asked. I noticed that Claudia and Mary Anne were both sitting on the floor — probably because I was hogging the bed, where they usually sit. Oops.

But Claudia didn’t look uncomfortable. She was reclining on this cool oversize pillow she’d covered in fake leopard skin and trimmed with gold braid. She looked glamorous and artistic and relaxed as she unwrapped the foil from a Hershey’s Kiss while she waited for Mary Anne to answer.

Claudia is way cool, no doubt about it. She’s also, artistically speaking, the most talented person I’ve ever met. Not only does she draw and paint really well, but she makes her own jewelry, customizes her clothes, and creates hairstyles that make your jaw drop.

Claudia is Japanese-American, with long black hair and beautiful dark almond-shaped eyes. She lives with her mom and dad and an older sister who is basically a genius. Claud’s grandmother Mimi used to live with the family, but she died before I moved here. I wish I could have met her. She sounds like the warmest, most accepting person in the world, and I know she was very important to Claudia. Mimi was supportive of everything Claudia did and never cared that she doesn’t do well in school (Claud even had to spend some time repeating seventh grade recently), or that she would live on junk food if she could, and would read nothing but Nancy Drew books. (Mr. and Mrs. Kishi do care about all of the above, so Claudia works hard to try to pull decent grades and is careful to hide her Milk Duds and her mysteries.)