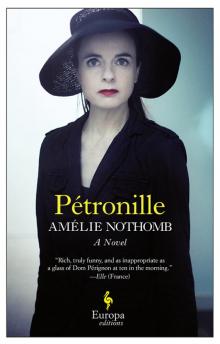

Pétronille

Amélie Nothomb

Europa Editions

214 West 29th St., Suite 1003

New York NY 10001

[email protected]

www.europaeditions.com

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2014 by Éditions Albin Michel

First publication 2015 by Europa Editions

Translation by Alison Anderson

Original Title: Pétronille

Translation copyright © 2015 by Europa Editions

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Cover Art by Emanuele Ragnisco

www.mekkanografici.com

Cover photo © Patrick Zwirc

ISBN 9781609453008

Amélie Nothomb

PÉTRONILLE

Translated from the French

by Alison Anderson

Intoxication doesn’t just happen. It’s an art, one that requires talent and application. Haphazard drinking leads nowhere.

While there is often something miraculous about the first time one gets really plastered, this is only thanks to proverbial beginner’s luck: by definition, it will not happen again.

For years, I drank the way most people do: depending on the party, I consumed drinks of varying strength, in hopes of reaching that state of heady inebriation which makes life bearable, and all I achieved for my pains was a hangover. And yet I have never stopped believing that my quest might be turned to better advantage.

My experimental temperament gained the upper hand. I was like those shamans in the Amazon who, before they begin to chew away on some unknown plant, subject themselves to draconian diets, the better to unveil its hidden powers; I resorted to the oldest investigatory technique on the planet: I fasted. Asceticism is an instinctive way to create the inner void that is indispensable to any scientific discovery.

There is nothing more depressing than people who, when they are about to taste a superior vintage, express their need to “nibble on something”: it is an insult to the food and an even greater one to the drink. “Otherwise, I’ll get tipsy,” they simper, aggravating their case. I feel like telling them they must not look at pretty girls, for fear of succumbing to their charms.

Drinking and wanting to avoid intoxication at the same time is as dishonorable as listening to sacred music while resisting any feeling of the sublime.

And so I fasted. And broke my fast with a Veuve Clicquot. The idea was to start with a good champagne, and thus the “Veuve” was not a bad choice.

Why champagne? Because champagne-induced intoxication is like no other. Every alcohol has its own particular armament; champagne is one of the only ones that does not inspire a vulgar metaphor. It elevates the soul toward a condition similar to that of a gentleman—in an era, that is, where that fine word still meant something. It makes one gracious, disinterested, light as air yet profound at the same time; it exalts love and confers elegance upon the loss of love. On these grounds I reasoned that here was an elixir that might turn my quest to better advantage.

And with the first sip I knew I was right: never had champagne tasted so exquisite. My thirty-six hours of fasting had sharpened my taste buds, and they detected even the faintest flavors in the alloy, quivering with a new sensual delight that started out virtuoso, quickly became brilliant, and ended transfixed.

Courageously, I continued drinking, and as I emptied the bottle I felt that the experience was changing in nature: what I attained did not deserve to be called intoxication so much as what is pompously referred to in today’s scientific parlance as “a heightened state of consciousness.” A shaman would have qualified it as a trance; a druggie would have called it a trip. I began to have visions.

It was six thirty in the evening, night was falling all around me. I looked into the darkest place and I saw, and heard, jewels. Their multiple fragments tinkled with precious gems, with gold and silver. Fragments that were animated by a serpentine crawling: they did not seek out the necks, wrists, or fingers they should have adorned, they were sufficient unto themselves and proclaimed the absolute nature of their luxury. As they approached me, I could feel their metallic chill. I felt the rapture of snow; I would have liked to bury my face in this frozen treasure. The most hallucinatory moment was when the palm of my hand actually felt the weight of a gemstone.

I let out a cry, which immediately dispelled the vision. I drank another glass and I understood that the potion was producing visions that resembled it: its golden color flowed into bracelets; its bubbles into diamonds. Every ice-cold sip brought a silvery chill.

The next stage was thought—if one can even qualify the current that bore my mind away as thought. At the opposite extreme from the ruminations which frequently bog it down, my mind began to twirl, to sparkle, to bluster with the most ethereal things: it was as if it sought to charm me. This was so unusual that I laughed out loud. I am so used to its recriminations, as if it were some tenant outraged by the shoddy quality of an apartment.

To be suddenly such pleasant company for my own self—this opened up new horizons. I would have liked to be similarly good company for someone. But for whom?

I went through all my acquaintances, among whom there were a good number of likeable souls. But there were none who suited the occasion. What I needed was someone who would agree to submit to extreme asceticism then drink with equal fervor. I could hardly subscribe to the notion that my ramblings might entertain a practitioner of sobriety.

In the meantime I had emptied the bottle and was dead drunk. I got to my feet and tried to walk; my legs marveled at the fact that under normal circumstances such a complicated dance would require no effort. I staggered to my bed and collapsed.

What an enchanting loss of self. I understood that the spirit of champagne approved of my behavior: I had welcomed it into my body as if it were an honored guest, I had shown it the highest regard, and in exchange it was showering me with its virtues. Until this final shipwreck, there was nothing that had not been a favor. If Ulysses had thrown caution to the winds and chosen not to lash himself to the mast, he would have come with me to the place where the ultimate power of the potion was leading, and he would have sunk with me to the bottom of the ocean, lulled by the golden chant of the Sirens.

I do not know how long I dwelled in that abyss, in a realm somewhere between sleep and death. I expected to feel comatose upon awakening, but I didn’t. When I emerged from my depths, I discovered yet another sensual delight: I was now made painfully aware of the slightest details of the comfort around me, as if I had been crystallized in sugar. The touch of clothing on my skin caused me to quiver, the bed that supported my frail self propagated a promise of love and understanding right to the marrow. My mind was marinating in a pool bubbling with ideas, in the etymological sense: an idea is first and foremost something one sees.

Thus, I could see that I was Ulysses, post-shipwreck, washed up on some unknown shore, and before I could draw up a plan I delighted in my astonishment at having survived, at having all my organs in one piece, along with a brain that was no worse affected than before, and that I now lay upon the solid part of the planet. My Parisian apartment was that unknown shore and I resisted the urge to go to the toilet, to preserve a moment longer my curiosity with regard to the mysterious tribe that I would surely meet there.

Upon reflection, that was the sole imperfection in my state: I would have liked to share it with someone. Nausicaa or the Cyclops would have fit the bill. Love or friendship would be ideal resonance chambers for so much wonder.

“I need a drinking companion,” I thought. I went through the list of peo

ple I knew in Paris, for I had only recently moved there. My few connections included people who were either extremely nice, but did not drink champagne, or real champagne drinkers who did not appeal to me in the least.

I managed to visit the bathroom. When I came back, I looked out the window at the restricted view of Paris there below me: pedestrians trudging through the dark shadows in the street. “Those are Parisians,” I thought, examining them as an entomologist would. “It seems impossible that with so many people out there I cannot find the Chosen One. In the City of Light, there must be someone with whom I can drink the Light.”

I was a thirty-year-old novelist who had recently moved to Paris. Booksellers invited me to come and do signings, and I never turned them down. People thronged to the bookstores to see me, and I greeted them with a smile. “How nice she is,” they would say.

In fact, in a passive sort of way, I was on the prowl. As I had fallen prey to my curious readers, I studied them all, and wondered what each of them would be like as a drinking companion. My own predatory attitude was ever so risky, because, in the end, how could I identify such an individual?

For a start, the word “companion” was all wrong: its etymology signifies the sharing of bread. It was a comvinion I needed. Some of the booksellers took the happy initiative to serve me wine, or even champagne, which allowed me to assess any flicker of desire in a customer’s eye. I liked it when they cast covetous looks at my glass, provided their gaze was not too intent.

The business of book signing is founded on a fundamental ambiguity: no one knows what the other person expects. How many journalists have asked me, “What do you hope to gain from this sort of encounter?” In my opinion, the question is even more pertinent when it applies to the other side. With the exception of the occasional fetishist for whom an author’s signature really matters, what are these autograph hunters looking for? And as for me, I am extremely curious about the people who come to see me. I try to find out who they are and what they want. And this will never cease to fascinate me.

Nowadays it is slightly less of a mystery. I am not the only one who has observed that the prettiest girls in Paris stand in line to meet me, and it amuses me no end that many people will come to a signing for the opportunity it offers to chat up one of these young beauties. And the circumstances are ideal: I am excruciatingly slow in writing my dedications, so the players have all the time in the world.

My story begins in late 1997. In those days, the phenomenon was less obvious, if for no other reason than I had fewer readers in those days, which reduces ipso facto the likelihood of such dreamlike creatures being found among them. Those were heroic times. Booksellers did not serve much champagne. I did not yet have an office at my publisher’s. I think back on this period with the same mixture of fear and emotion as does our species when remembering prehistoric times.

At first glance, I thought she looked so terribly young that I mistook her for a fifteen-year-old boy. Her youthfulness was confirmed by the exaggerated intensity of her eyes: she was staring at me as if I were the skeleton of the Glyptodon at the Jardin des Plantes.

I am read by a good number of adolescents. When the lycée has imposed one of my books on its pupils, it makes for only moderately interesting reading. But when kids themselves take the initiative to read me—now that is fascinating. And so I greeted the boy with genuine enthusiasm. He was on his own, proof that it wasn’t a teacher who had sent him.

He handed me a copy of Loving Sabotage. I opened it to the flyleaf and uttered the ritual phrase: “Good evening. Who would you like me to make it out to?”

“Pétronille Fanto,” answered a voice that was quite gender neutral, although slightly more feminine than masculine.

I was startled, not so much by my discovery of the individual’s true gender as by her identity.

“It’s you!” I cried.

How many times when signing have I experienced this moment: there before me stands someone with whom I have been corresponding. It is always such a shock. To go from an encounter on paper to an encounter in the flesh implies a complete change of dimension. I don’t even know if it means going from the second to the third dimension, because perhaps it is the opposite. Often when I meet the actual correspondent, there is a regression, and I lapse into platitudes. And the awful thing is that this is irremediable: if the other person’s appearance, for God knows whatever reason, does not match the loftiness of our correspondence, then our correspondence will never attain that level again. It is impossible to forget or to disregard. Or impossible for me, at any rate. Which is absurd, because there is nothing remotely romantic about these exchanges. It would be an error to think that looks are only important where love is concerned. For the majority of people, myself included, looks also matter in friendship, and even in the most elementary relationships. I’m not referring to beauty or ugliness, but rather to that thing that is so vague and so vital and which we call physiognomy. Right from the start, there are those with whom we feel great affinity, and other unlucky individuals whom we simply cannot stand. To deny this would only compound the injustice.

Of course, this can change: there are some people whose appearance is off-putting but who are so wonderful that you can learn to live with it, or even learn to like the way they look. And the reverse also holds true: people with particularly good looks gradually begin to lose their charm if we do not care for their personality. Regardless, we have to come to terms with this basic premise. And the moment we meet is the moment we suddenly take the measure of the other person’s physical attributes.

“It’s me,” answered Pétronille.

“You’re not how I imagined,” I could not help but say.

“How did you imagine me?” she asked.

Which she was bound to say, after my idiotic declaration. In fact I had not imagined her one way or the other. When you are corresponding with someone, it’s not an image you form so much as a vague intuition of the recipient’s appearance. Pétronille Fanto, over the last three months, had sent me two or three handwritten letters in which she had not told me her age. She had written such deep, tenebrous things that I thought I must be dealing with someone who was approaching old age. And here I was face to face with a teenager with a chili pepper gaze.

“I thought you were older.”

“I’m twenty-two,” she said.

“You look younger.”

She rolled her eyes, visibly annoyed, and this made me want to laugh.

“What do you do in life?”

“I’m a student,” she said, and no doubt to curtail the obvious follow-up question, she added, “I’m doing a master’s in Elizabethan literature. I’m writing my dissertation on one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries.”

“Remarkable! Which contemporary might that be?”

“You wouldn’t know him,” she answered, perfectly composed.

I burst out laughing.

“And you find the time to read my books between Marlowe and John Ford?”

“I’m allowed to have fun from time to time.”

“I’m pleased to be your entertainment,” I said, to conclude.

I would gladly have gone on talking to her, but she was not the last one in line. Each encounter with a reader must be brief, which more often than not is a relief. I wrote a few words on the title page of her copy of Loving Sabotage. I have no idea what I might have written. Without exception, what matters to me at a book signing is certainly not the actual signing.

There are two attitudes possible among the people whose book I have just signed: either they go away with their booty, or they go off to one side to watch me until the end of the session. Pétronille stayed and watched. I felt as if she were planning to make a wildlife documentary about me.

The signing was held at that marvelous, tiny bookshop in the seventeenth arrondissement, L’Astrée, at 69 Rue de Lévis. Michèle and Alain Lemoine

always welcomed authors and readers with disarming kindness. As it was already very cold out on that late October night, they offered everyone a glass of mulled wine. I was enjoying my drink, and I noticed that Pétronille was not exactly ignoring her own glass.

She really did look like a fifteen-year-old boy: even her long hair, held back in an elastic, was like an adolescent’s.

Suddenly up came a professional photographer who started snapping away without asking my permission. To keep from getting annoyed, I pretended I hadn’t noticed his little game and I went on meeting my readers. Before long the lout was no longer content with merely being ignored and he started waving at people to move to one side. Smoke was pouring from my ears and I interceded:

“Monsieur, I am here for my readers, not for you. Therefore you have no business giving orders to anyone.”

“I’m working for your fame and fortune,” said the sycophant, continuing to snap away.

“No, you are working for your own bank account, and you are rude. You have already taken plenty of pictures. That’s enough.”

“This is a violation of freedom of the press!” said the man, establishing his true identity as a paparazzo.

Michèle and Alain Lemoine were horrified by what was going on in their bookstore (named for a seventeenth-century novel), yet they did not dare intercede. In the end it was Pétronille who grabbed the fellow by the scruff of the neck and dragged him outside with unswerving determination.

I never found out what happened, exactly, but I did not see the snap-happy scoundrel again, and none of his photographs turned up in the press.

No one mentioned the incident. I went on signing books with a smile. And then the booksellers, a few faithful customers and I finished off the mulled wine and chatted. I said good night, and headed for the Métro station.

Because it was dark, initially I did not see the little figure waiting for me at the end of the Rue de Lévis.