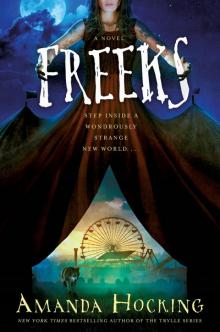

Freeks

Amanda Hocking

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

There is no exquisite beauty without some strangeness in the proportion.

—EDGAR ALLAN POE

prologue

Behind me, the branches and trees crunched and snapped as the creature tore through them.

I didn’t scream—there was no one who could come to help me, nothing that could stop the monster that lurched behind me. The only thing I could do was run faster.

Then the ground gave way beneath me. Under the pale moonlight, the tall grass and thick forest made it hard for me to see where I was going, and it was already too late when I felt my foot squelching down into the dense mud of the surrounding swamp.

I fell forward and tried to climb to higher ground, but the ground had swallowed my legs up. There wasn’t enough time for me to get free.

It was close enough that I could smell the sulfur on its breath. I could hear the beast behind me—it made a strange high-pitched guttural sound, like a demonic squeal of delight.

Grabbing a broken branch, I turned around to face the creature as it tore through the trees toward me. I brandished the branch like a weapon. If I was going down, I was going down swinging.

1. premonitions

My feet rested against the dashboard of the Winnebago as we lumbered down the road, the second vehicle in a small caravan of beat-up trailers and motorhomes.

The sun hadn’t completely risen yet, but it was light enough that I could see outside. Not that there was much to see. The bridge stretched on for miles across Lake Tristeaux, and I could see nothing but the water around us, looking gray in the early morning light.

The AC had gone out sometime in Texas, and we wouldn’t have the money to fix it until after this stint in Caudry, if we were lucky. I’d cracked the window, and despite the chill, the air felt thick with humidity. That’s why I never liked traveling to the southeastern part of the country—too humid and too many bugs.

But we took the work that we got, and after a long dry spell waiting in Oklahoma for something to come up, I was grateful for this. We all were. If we hadn’t gotten the recommendation to Caudry, I’m not sure what we would’ve done, but we were spending our last dimes and nickels just to make it down here.

I stared ahead at Gideon’s motorhome in front of us. The whole thing had been painted black with brightly colored designs swirling around it, meant to invoke images of mystery and magic. The name “Gideon Davorin’s Traveling Sideshow” was painted across the back and both the sides. Once sparkles had outlined it, but they’d long since worn off.

My eyelids began to feel heavy, but I tried to ward off sleep. The radio in the car was playing old Pink Floyd songs that my mom hummed along to, and that wasn’t helping anything.

“You can go lay down in the back,” Mom suggested.

She did look awake, her dark gray eyes wide and a little frantic, and both her hands gripped the wheel. Rings made of painted gold and cheap stones adorned her fingers, glinting as the sun began to rise over the lake, and black vine tattoos wrapped around her hands and down her arms.

For a while, people had mistaken us for sisters since we looked so much alike. The rich caramel skin we both shared helped keep her looking young, but the strain of recent years had begun to wear on her, causing crow’s-feet to sprout around her eyes and worried creases to deepen in her brow.

I’d been slouching low in the seat but I sat up straighter. “No, I’m okay.”

“We’re almost there. I’ll be fine,” she insisted.

“You say we’re almost there, but it feels like we’re driving across the Gulf of Mexico,” I said, and she laughed. “We’ve probably reached the Atlantic by now.”

She’d been driving the night shift, which was why I was hesitant to leave her. We normally would’ve switched spots about an hour or two ago, with me driving while she lay down. But since we were so close to our destination, she didn’t see the point in it.

On the worn padded bench beside the dining table, Blossom Mandelbaum snored loudly, as if to remind us we both should be sleeping. I glanced back at her. Her head lay at a weird angle, propped up on a cushion, and her brown curls fell around her face.

Ordinarily, Blossom would be in the Airstream she shared with Carrie Lu, but since Carrie and the Strongman had started dating (and he had begun staying over in their trailer), Blossom had taken to crashing in our trailer sometimes to give them privacy.

It wasn’t much of a bother when she slept here, and in fact, my mom kind of liked it. As one of the oldest members of the carnival—both in age and in the length of time she’d been working here—my mom had become a surrogate mother to many of the runaways and lost souls that found us.

Blossom was two years younger than me, on the run from a group home that didn’t understand her or what she could do, and my mom had been more than happy to take her under her wing. The only downside was her snoring.

Well, that and the telekinesis.

“Mara,” Mom said, her eyes on the rearview mirror. “She’s doing it again.”

“What?” I asked, but I’d already turned around to look back over the seat.

At first I didn’t know what had caught my mom’s eye, but then I saw it—the old toaster we’d left out on the counter was now floating in the air, hovering precariously above Blossom’s head.

The ability to move things with her mind served Blossom well when she worked as the Magician’s Assistant in Gideon’s act, but it could be real problematic sometimes. She had this awful habit of unintentionally pulling things toward her when she was dreaming. At least a dozen times, she’d woken up to books and tapes dropping on her. Once my mom’s favorite coffee mug had smacked her right in the head.

“Got it,” I told my mom, and I unbuckled my seat belt and went over to get it.

The toaster floated in front of me, as if suspended by a string, and when I grabbed it, Blossom made a snorting sound and shifted in her sleep. I turned around with the toaster under my arm, and I looked in front of us just in time to see Gideon’s trailer skid to the side of the road and nearly smash into the guardrail.

“Mom! Look out!” I shouted.

Mom slammed on the brakes, causing most of our possessions in the trailer to go hurtling to the floor, and I slammed into the seat in front of me before also falling to the floor. The toaster slipped from my grasp and clattered into the dashboard.

Fortunately, there was no oncoming traffic, but I could hear the sound of squealing tires and honking behind us as the rest of the caravan came to an abrupt stop.

“What happened?” Blossom asked, waking up in a daze from where she’d landed beneath the dining table.

“Mara!” Mom had already leapt from her seat and crouched in front of where I still lay on the worn carpet. “Are you okay?”

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I assured her.

“What about you?” Mom reached out, brushing back Blossom’s frizzy curls from her face. “Are you all right?”

Blossom nodded. “I think so.”

“Good.” That was all the reassurance my mom needed, and then she was on her feet and jumping out of the Winnebago. “Gideon!”

“What happened?” Blossom asked again, blinking the sleep out of her dark brown eyes.

“I don’t know. Gideon slammed on his brakes for some reason.” I stood up, moving much slower than my mother.

We had

very narrowly avoided crashing into Gideon. He’d overcorrected and jerked to the other side of the road, so his motorhome was parked at an angle across both lanes of the highway.

“Is everyone okay?” Blossom had sat up, rubbing her head, and a dark splotch of a bruise was already forming on her forehead. That explained why she seemed even foggier than normal—she’d hit her head pretty good.

“I hope so. I’ll go check it out,” I said. “Stay here.”

By the time I’d gotten out, Seth Holden had already gotten out of the motorhome behind us. Since he was the Strongman, he was usually the first to rush into an accident. He wanted to help if he could, and he usually could.

“Lyanka, I’m fine,” Gideon was saying to my mother, his British accent sounding firm and annoyed.

“You are not fine, albi,” Mom said, using a term of affection despite the irritation in her voice.

I rounded the back of his motorhome to find Gideon leaning against it with my mom hovering at his side. Seth reached them first, his T-shirt pulled taut against his muscular torso.

“What’s going on? What happened?” Seth asked.

“Nothing. I just dozed off for a second.” Gideon waved it off. “Go tell everyone I’m fine. I just need a second, and we’ll be on our way again.”

“Do you want me to drive for you?” Seth asked. “Carrie can handle the Airstream.”

Gideon shook his head and stood up straighter. “I’ve got it. We’re almost there.”

“All right.” Seth looked uncertainly at my mom, and she nodded at him. “I’ll leave you in Lyanka’s care and get everyone settled down.”

As soon as Seth disappeared back around the motorhome, loudly announcing that everything was fine to everyone else, Gideon slumped against the trailer. His black hair had fallen over his forehead. The sleeves of his shirt were rolled up, revealing the thick black tattoos that covered both his arms.

“Gideon, what’s really going on?” Mom demanded with a worried tremor.

He swallowed and rubbed his forehead. “I don’t know.”

Even though the sun was up now, the air seemed to have gotten chillier. I pulled my sweater tighter around me and walked closer to them. Gideon leaned forward, his head bowed down, and Mom rubbed his back.

“You didn’t fall asleep, did you?” I asked.

Gideon lifted his eyes, looking as though he didn’t know I was there. And guessing by how pained he was allowing himself to look, he probably hadn’t. Gideon was only in his early thirties, but right now, he appeared much older than that.

That wasn’t what scared me, though. It was how dark his blue eyes were. Normally, they were light, almost like the sky. But whenever he’d had a vision or some kind of premonition, his eyes turned so dark they were nearly black.

“It was a headache,” Gideon said finally.

“There’s something off here,” Mom said. “I felt it as soon as we got on the bridge. I knew we should turn back, but I hoped that maybe I was imagining things. Now that I look at you, I know.”

That explained that frantic look in her eyes I’d seen earlier in the Winnebago, and how alert she’d been even though she’d been awake and driving for nearly twenty hours straight. Mom didn’t see things in the way Gideon did, but she had her own senses.

“It’s fine, Lyanka,” Gideon insisted. He straightened up again, and his eyes had begun to lighten. “It was only a migraine, but it passed. I am capable of having pain without supernatural reasons too.”

Mom crossed her arms over her chest, and her lips were pressed into a thin line. “We should go back.”

“We’re almost there.” Gideon gestured to the end of the road, and I looked ahead for the first time and realized that we could see land. The town was nestled right up to the lake, and we couldn’t be more than ten minutes outside the city limits.

“We could still turn around,” Mom suggested.

“We can’t.” He put his hands on her arms to ease her worries. “We don’t have any money, love. The only way we can go is forward.”

“Gideon.” She sighed and stared up at the sky, the violet fabric of her dress billowing out around her as the wind blew over us, then she looked back at him. “Are you sure you’re okay to drive?”

“Yes, I’m sure. Whatever pain I had, it’s passed.” He smiled to reassure her. “We should go before the others get restless.”

She lowered her eyes, but when he leaned in to kiss her, she let him. She turned to go back to our motorhome, and as she walked past me, she muttered, “I knew we should never travel on Friday the thirteenth. No good ever comes of it.”

I’d waited until she’d gone around the corner to turn back to Gideon, who attempted to give me the same reassuring smile he’d given my mom.

“We could go back,” I said. “There’s always a way. We’ve made it on less before.”

“Not this time, darling.” He shook his head. “And there’s no reason to. Leonid assured me there’d be a big payday here, and I’ve got no reason to doubt him. We can make a go of it here.”

“As long as you’re sure we’ll be okay.”

“I haven’t steered you all wrong yet.” Gideon winked at me then, but he was telling the truth. In the ten years that my mom and I had been following him around the country, he’d always done the best he could by us.

I went back and got into the Winnebago with my mom and Blossom. Within a couple minutes, Gideon had straightened out his motorhome, and the caravan was heading back down the road. At the end of the bridge was a large sign that read WELCOME TO CAUDRY, POPULATION 13,665.

As soon as we crossed the line into town, the air seemed even colder than before. That’s when I realized the chill wasn’t coming from outside—it was coming from within me.

2. caudry

Pulling my denim jacket tighter around me, I wandered down the streets of Caudry. After spending the day setting up, I’d decided to go out on my own and explore the town for myself. Despite the initial dark premonitions, setup had been rather uneventful.

Camp had been set up on the edge of town, right along a thick forest that bled into the wetlands, behind the fairgrounds. If I ventured too far from the trailers in the wrong direction, the ground gave way to sticky mud hidden in tall grass. The trees around seemed to bend forward and lean down, as if their branches were reaching out for us. Long vines and Spanish moss grew over everything, and I swore I’d never seen a place so green before.

After the sun finally set and the heat of the day began to break, everyone settled in, happy to rest after many hours on the road. All of the base camp was set up, and we’d begun getting the carnival ready to open tomorrow afternoon.

Even though I hadn’t gotten much sleep, I was too restless to just stay in the motorhome. I slid out quietly, moving between the trailers to avoid someone stopping me or asking to tag along. Living in the carnival like this meant I was almost never alone, and sometimes I just needed to get out by myself and clear my head.

I didn’t have to walk that far until I’d made it into Caudry town proper, and it was just as green as the outskirts of town where we were camped. Buildings seemed prone to a mossy growth on their sides, and the streetlamps had orbs of light glowing around them, thanks to the humidity.

While the center of town appeared more like any of the other hundreds of towns I’d visited before—all bright and clean and shiny and new—the peripheral parts were like ghostly reminders of a long history. I stuck to the side streets, hiding away from the glossier parts of Caudry.

On a street called Joliet Avenue, I found an area that must have been glorious in its prime. Huge houses verging on mansions lined the streets, hidden behind willows and cypresses towering above them. The streets were cobblestone, but they had begun to wear and crack, with grass and weeds growing up between them.

As I walked down the street, I heard the faint sounds of a party several houses down. It was a strange juxtaposition of the fading gothic beauty of the neighborhood with the rock

music—one of Bon Jovi’s latest hits, “You Give Love a Bad Name”—and new cars parked in front of it.

A wrought-iron fence separated me from the party house. Large stone posts flanked either side of an open gate, and I paused at the end of the driveway. It curved in front of the house, and it was overflowing with parked cars, including a cherry red ’86 Mustang that stood out sharply against the white mansion.

Every window in the house was on, making the house glimmer on the darkened street. At one time, it had probably been nestled on the edge of a plantation, but the town had grown up around it, burying it in suburban streets and overgrown trees.

White streamers were strung from the overhanging branches of the trees, making it seem as if the trees had extended their grasp, reaching closer to the ground to snatch anyone who got close.

The house loomed over the street, reminding me of a monster from a slasher flick, and neither the neon balloons attached to columns nor the brightly dressed partygoers could shake it.

It was a massive two-story white antebellum manor, with a balcony supported by thick columns. Some of the party guests had drifted out onto it, singing along to the music that blasted from the stereo.

Still standing on the cobblestones at the end of the driveway, I was near enough that I could see the people fairly well, dancing and laughing on the brightly lit balcony. A guy sat on the railing of the second-floor balcony, drinking from a red plastic cup.

With his back to the street, the popped collar of his silver blazer blocked his face. Slowly, he turned away from the party. His brown hair was pushed back, and he surveyed the parking lot that the front yard had become.

Then I felt his eyes settle on me. I was hidden in the shadows of the street, so he wouldn’t be able to see me. Or at least he shouldn’t have been able to. But there was something about his expression—the furrow of his brow, the shadow across his eyes—and I was certain that he was looking right at me.

I smiled at him and tried to quiet my heart hammering in my chest. There was nothing about this that should have my pulse racing so fast. But then he returned my smile.