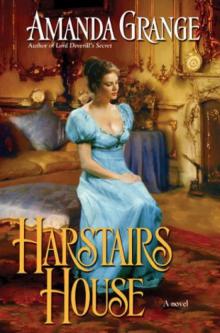

Harstairs House

Amanda Grange

Harstairs House

By

Amanda Grange

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Books by Amanda Grange

MR. KNIGHTLEY'S DIARY

LORD DEVERILL'S SECRET

HARSTAIRS HOUSE

HARSTAIRS HOUSE

Copyright © 2004 by Amanda Grange

Berkley Sensation trade paperback

ISBN 978-0-425-21773-3

CHAPTER ONE

Miss Susannah Thorpe looked out at the dismal November morning in the year of 1793 and sighed. The dull sky had leeched the colour from the gardens and reduced them to a dreary shade of grey. A few last leaves, clinging to the trees, were drenched by the pouring rain. At least when she had been appointed as a governess to the Russell children it had been the start of summer, and the warm, sunny weather had allowed her to take them into the garden. But today, for the tenth day in succession, they would be confined to the schoolroom, which meant their behaviour would be dreadful.

The clock struck the hour. She wrapped a shawl round her shoulders and tidied her mouse-brown hair, then made her way to the schoolroom. The children were already there, being supervised by their nurse, Mrs. Hitchins, who smiled benignly as Master Thomas pulled Miss Isabelle's pigtails. " 'E's a proper boy, 'e is," said Mrs. Hitchins indulgently, as she passed Susannah on her way out of the room.

He's a proper monster, thought Susannah, but did not say so. She knew that anything she said to the nurse would be reported to Mrs. Russell, and such a remark could easily lead to her being dismissed.

Master David, meanwhile, was kicking Master Julian, who was about to retaliate by pouring ink over his brother's head. Susannah prayed for patience then set about restoring order. She coaxed the children to their desks and then she handed out their slates. As soon as she handed one to Master David, he drew his fingernails across it and smiled with glee as a ghastly screeching noise filled the schoolroom. When Master Julian decided to copy him, Susannah prepared herself for yet another nerve-jangling day.

Hardly had it begun, however, when the door opened and one of the housemaids entered.

"You're wanted downstairs," the housemaid said to Susannah.

Susannah's spirits sank. What had she done this time? The children were forever bearing tales, and she was constantly being reprimanded for imaginary grievances.

"You'd better 'urry," said the maid.

"What about the children?" asked Susannah.

The boys were already flicking pieces of chalk across the room.

"I'm to stay with 'em until you get back," said the housemaid warily.

Master David whooped with glee, whilst Master Julian began pulling faces at the hapless girl.

Susannah might be going to receive a scold, but she was beginning to think she would rather face one of Mrs. Russell's tirades than deal with the children's unruly behaviour.

How had it come to this? she thought, as she descended the stairs and then crossed the hall. Two years before, she had been a happy young lady from a poor but respectable family. Her mother having died at her birth, her father had raised her in a small cottage by the sea, but when she was eleven he, too, had died, and she had been raised by her Great Aunt Caroline. Time had taken its toll, and Great Aunt Caroline had at last passed away, leaving Susannah alone in the world. A post as a companion had followed, but when her elderly employer had emigrated, Susannah had been forced to seek another position, this time as a governess in the Russell household.

She paused outside the drawing-room door to straighten her skirt, then she knocked on the door and Mrs. Russell's querulous voice called, "Come in."

She opened the door to reveal a splendid apartment with gold-painted walls, a marble fireplace carved with two female figures, and a collection of damask chairs and sofas. Lying in front of the fireplace on a chaise longue, dressed in an enchanting gown of gold silk, was Mrs. Russell. Having convinced herself that she was delicate, Mrs. Russell spent her days moving from her bed to her chaise longue and back again in a never-ending cycle of bodily inactivity, so that her mind was free to find fault with everyone and everything about her.

"What took you so long?" asked Mrs. Russell, in a peevish voice. "Mr. Sinders has been waiting for you for ten minutes. Really, girl, you should know better than to dawdle when you are sent for. Other people's time is valuable, even if yours is not."

Mr. Sinders raised his eyebrows at this speech, but said nothing except, "How do you do, Miss Thorpe."

"How do you do," said Susannah, eyeing him cautiously.

Mr. Sinders was an elderly man with the look of a doctor or other professional person about him. His clothes were smart, but not smart enough to threaten his employers' superiority by being too well cut, or made of too fine a cloth. His tailcoat was black with large gilt buttons and his knee breeches were tucked into white stockings. On his feet he wore black shoes.

"Mr. Sinders has come all the way from London to see you," said Mrs. Russell "You might at least seem pleased to see him."

A look of distaste crossed Mr. Sinders's face at Mrs. Russell's renewed ill humour.

"May we have somewhere private to discuss our business?" he asked.

"Anything you have to say to Miss Thorpe may be said in front of me," Mrs. Russell declared.

"Unfortunately, I'm not at liberty to discuss the matter with anyone else," said Mr. Sinders firmly.

Mrs. Russell's mouth set in a petulant line.

"I am not anyone else: I am Miss Thorpe's employer, and naturally I take a motherly interest in her welfare," she said.

Mr. Sinders raised his eyebrows at this blatant lie, but he did not contradict Mrs. Russell. Instead, he said, "Nevertheless, I am bound by my profession to honour Mr. Harstairs's edicts."

He spoke politely, but there was a note of steel in his voice, and it told Susannah he would not be swayed.

"Very well," said Mrs. Russell peevishly. "Morton, show Mr. Sinders to the library, and do hurry up. No, leave your knitting. Whatever that misshapen garment is, it can wait. Go now, at once. And take care you don't bore him to death with your prattle."

Miss Morton, an ageing spinster who had the dubious pleasure of being Mrs. Russell's companion, sprang to her feet and led the way out of the room, murmuring, "Oh, of course, yes indeed, let me show you the way."

Flustering and fluffing, Miss Morton led Susannah and Mr. Sinders through the hall to the back of the house, where she opened a door into the library. It was a spacious apartment lined with books, and had a buttoned leather sofa set in front of the fireplace. Wing chairs were placed on either side of it, and behind it, tall windows looked out on to the dreary garden.

"Thank you," said Mr. Sinders politely, making Miss Morton a bow.

"Oh, thank you" she fluttered, unused to such civil treatment. She smiled nervously at Susannah and then departed, closing the door behind her.

"Won't you be seated?" asked Mr. Sinders.

Susannah sat on the sofa and arranged the folds of her gown to hide a patch on the hem.

"I expect you are wondering who I am," said Mr. Sinders, as he sat down in one of the wing chairs.

"Yes, I am," said Susannah.

"I represent Mr. Harstairs; I am his lawyer."

"I have never heard of Mr. Harstairs," said Susannah.

"Mr. Harstairs was once betrothed to your Great Au

nt Caroline," said Mr. Sinders.

Susannah's eyes opened wide in surprise. Great Aunt Caroline had never mentioned any love affairs, and Susannah had assumed she had passed through life unruffled by its passions.

"I never knew Great Aunt Caroline had been betrothed," she said.

"Once, many years ago. There was a misunderstanding, and the wedding was abandoned. Mr. Harstairs threw himself into his business, going abroad for many years. When he returned he was a wealthy man. He never married and, in short, when he died, he left everything to you."

"To me?" asked Susannah in astonishment.

"Yes, to you."

"But why?"

"You are all that is left of the woman he loved," said Mr. Sinders simply. "I should say, before I go any further, that your inheritance is subject to certain conditions. They are somewhat unusual. In order to claim your inheritance—a large one, I might add; one that would relieve you of the necessity of earning your own living, and allow you to live in comfort for the rest of your life — you must either marry within a month from today, or you must spend a month in Harstairs House."

"That doesn't seem too difficult," said Susannah. "Since I know no gentlemen, and have no intention of marrying a gentleman I don't know, I will not be able to carry out the first option, but I see no difficulty in carrying out the second."

Mr. Sinders pursed his lips and steepled his fingers, then leant back in his chair.

"I should perhaps warn you that Harstairs House is said to be haunted," he remarked.

Susannah laughed. "I have been a governess to the Russell children for three months, two weeks and five days, Mr. Sinders. There is nothing a ghost can do to frighten me after that!"

Mr. Sinders gave a dry smile.

"It does not seem a congenial household," he admitted. "But think carefully. Marriage would be an easier option, and with such a fortune you would be able to have your pick of husbands. If you decide to inhabit Harstairs House, I must tell you that you will be isolated for an entire month, for it is set on a promontory overlooking the Cornish coast. Then there is the fact that you would have to take up residence at once."

"I have nothing to stay here for," said Susannah. She thought for a moment and then said, "If I go to Harstairs House and don't remain for a month, what then?"

"You will be awarded an amount of money for each night you pass there: ten pounds for the first night, twenty for the second night, forty for the third, eighty for the fourth and so on."

"So the longer I stay, the greater my reward," mused Susannah.

"Exactly."

"And if I stay the full month?" she asked.

"Then you will inherit the house, and a fortune of one hundred thousand pounds."

"One hundred… ?" Susannah was speechless.

"Thousand pounds," Mr. Sinders finished for her. "There is a coach waiting outside. In order to fulfil the terms of the will, if you choose to spend a month in the house, you must set out today."

Susannah did not need to think about it. Anything must be better than teaching the Russell children for another month. It would either turn her grey or send her to Bedlam!

"May I take someone with me?" she asked.

Mr. Sinders looked surprised.

"I don't know," he said. "There is nothing in the will that says you can't, so yes, I suppose that would be all right. Do you have anyone in mind?"

"I do," said Susannah. She stood up. "I will go and ask her if she would like to join me, and then I will pack. It will not take me long, half an hour at most."

Mr. Sinders stood up, too.

"Then I will await you here. Mr. Harstairs made provision for a hired coach to bring me here, and then to take you down to Cornwall. It is a journey on which I am bound to accompany you, to see you safely installed in the house. As soon as you are ready, we will drive there together," he said.

Half an hour later, Susannah was sitting in a smart coach with a travelling cloak thrown over her gown, feeling overjoyed to have left the Russells behind. She did not know what the future held, but she was sure it must be better than the recent past. She cast her eyes round the coach, which was spacious, and fitted out in the first style. There was a writing desk built into it, and the squabs were made of green leather, perfumed with the smell of polish. The coach was comfortable, being well sprung, and it was pulled by a team of horses who made light work of the miles. On the opposite seat sat Mr. Sinders, and next to Susannah sat Miss Constance Morton.

"So good," said Constance for the tenth time, in a daze. "I don't know what I've done to deserve such good fortune, but thank you, Susannah, from the bottom of my heart."

Susannah had not known whether Constance would agree to the scheme, thinking that a haunted house might be too alarming for her, but she had asked nonetheless. Constance had been extremely kind to her when she had first arrived at the Russells' house, making her feel welcome, and comforting her when Mrs. Russell had been particularly spiteful, and she had wanted to repay that kindness. She smiled as she recalled Constance's face when she had mentioned the idea. It had been a picture! Miss Morton had been startled, and had then flushed pink with pleasure before saying, "I am sure ghosts won't bother me. I will simply sit in a corner with my knitting, and once they have seen I am not to be scared, I am sure they will go away."

"I have not been able to hire any servants," said Mr. Sinders, as the coach rattled on its way. "It might be possible to find someone to work there as winter sets in and other work grows scarce, but for now I am afraid you will have to fend for yourselves."

"Please don't worry about it," said Susannah. "I can cook and clean. In fact, I will enjoy it. It will be nice to have hot meals for a change."

Mr. Sinders looked at her enquiringly.

"My meals were brought up to me on a tray at Mrs. Russell's. The food was always cold by the time it reached me in the nursery," she explained.

"Ah," said Mr. Sinders, nodding. "There will be no such difficulty at Harstairs House."

"Will there be everything we need at the house, linen and such like?"

"Yes, everything is there. It's an old, ramshackle building, but the roof is sound and the chimneys have been swept. The only thing you might find uncomfortable are the draughts. Sudden bursts of cold air can set the doors and windows banging, alarming those who are nervous."

"We will just have to wear our shawls!" Susannah said.

"If you should regret your decision and wish to leave the house, there is a village five miles away. It will not take you much more than an hour to walk the distance. If you do, though, remember you will forfeit your inheritance," said Mr. Sinders.

"And how would you know if we left?" asked Susannah curiously. "If we had a mind to, what is to prevent us from staying the month at a nice, cosy inn and then claiming to have spent it at Harstairs House?"

He gave a dry smile. "Nothing. But if you give me your word you have not left, I will accept it. You are free to wander in the grounds, but if you go through the gate or across the fences, you will lose everything but the allowance for the number of nights you have spent in the house."

"Mr. Harstairs must have been a strange gentleman," said Susannah thoughtfully.

"Mr. Harstairs was something of an eccentric. His eccentricity, combined with the attention to detail he gave to his business matters, made him appear rather odd. But I believe he was quite sane."

As the coach bowled through the country lanes, they fell silent. Susannah tried to imagine the gentleman who had fallen in love with Great Aunt Caroline. He must have loved her a great deal, she reflected, for he had never married, and had left all his possessions to Caroline's great-niece.

She leaned back against the comfortable squabs. It was the first piece of good fortune she had had since Aunt Caroline had taken her in, and she was already looking forward to her inheritance. When the month was over, she meant to enjoy her new-found wealth. London shops, with their silk gowns, lace shawls and fetching hats beckoned her. There would be

rides in the park, museums, assemblies… Susannah fell into a happy reverie as the coach travelled south.

It was dark when the coach finally turned off the road and began to make its way down a narrow lane. As it progressed, Susannah heard a faint swishing noise in the distance. It gradually grew louder, and at last she realized that it was the sea!

"Does Harstairs House have a way down to the shore?" she asked Mr. Sinders with interest.

"It does," he replied.

"I haven't seen the sea for years," said Susannah wistfully. "But I don't suppose I will see it tonight."

She peered out of the window, but the moon was obscured by clouds, and the few stars that pierced the blackness could do no more than shed a faint, silvery light on the world below.

"The village is that way," said Mr. Sinders, pointing down an even narrower lane to their left. "It is marked with a signpost, do you see?"

Susannah nodded as the coach rolled past the post. She could just read the word Harding and the number 1 3/4 by the light of the coach lamps. She made an effort to memorize the way, in case she should need it in the future.

At last the coach slowed and turned into an imposing set of gates a little further up the lane.

"This marks the point beyond which you cannot go," said Mr. Sinders.

The coach wound up a long drive bordered by open ground, and then turned a corner to reveal a huge house. It was the oddest building Susannah had ever seen. It had none of the grace and beauty of Mrs. Russell's home, with its symmetrical façade and tall windows. Instead, it looked as though it had been thrown up by a violent upheaval of the land.

"It used to be a farmhouse," said Mr. Sinders. "When it burned down, its owner restored it and added to it, but he had little use for architects and built for practicality. I am not a connoisseur of such things, but even I can see that it is ugly."

"It's a monstrosity," Susannah agreed.