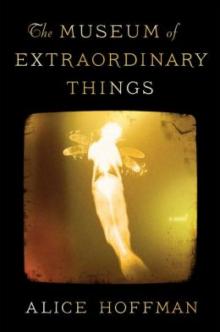

The Museum of Extraordinary Things

Alice Hoffman

CONTENTS

Epigraph

One The World in a Globe

Two The Man Who Couldn’t Sleep

Three The Dreamer from the Dream

Four The Man Who Felt No Pain

Five The Original Liar

Six The Birdman

Seven The Wolf’s House

Eight The Blue Thread

Nine The Girl Who Could Fly

Ten The Rules of Love

The World Begins Again

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the

beginning and the end.

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

—Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

ONE

* * *

THE WORLD IN A GLOBE

**********

YOU WOULD THINK it would be impossible to find anything new in the world, creatures no man has ever seen before, one-of-a-kind oddities in which nature has taken a backseat to the coursing pulse of the fantastical and the marvelous. I can tell you with certainty that such things exist, for beneath the water there are beasts as huge as elephants with hundreds of legs, and in the skies, rocks thrown alit from the heavens burn through the bright air and fall to earth. There are men with such odd characteristics they must hide their faces in order to pass through the streets unmolested, and women who have such peculiar features they live in rooms without mirrors. My father kept me away from such anomalies when I was young, though I lived above the exhibition that he owned in Coney Island, the Museum of Extraordinary Things. Our house was divided into two distinct sections; half we lived in, the other half housed the exhibitions. In this way, my father never had to leave what he loved best in the world. He had added on to the original house, built in 1862, the year the Coney Island and Brooklyn Railroad began the first horse-drawn carriage line to our city. My father created the large hall in which to display the living wonders he employed, all of whom performed unusual acts or were born with curious attributes that made others willing to pay to see them.

My father was both a scientist and a magician, but he declared that it was in literature wherein we discovered our truest natures. When I was only a child he gave me the poet Whitman to read, along with the plays of Shakespeare. In such great works I found enlightenment and came to understand that everything God creates is a miracle, individually and unto itself. A rose is the pinnacle of beauty, but no more so than the exhibits in my father’s museum, each artfully arranged in a wash of formaldehyde inside a large glass container. The displays my father presented were unique in all the world: the preserved body of a perfectly formed infant without eyes, unborn monkey twins holding hands, a tiny snow-white alligator with enormous jaws. I often sat upon the stairs and strained to catch a glimpse of such marvels through the dark. I believed that each remarkable creature had been touched by God’s hand, and that anything singular was an amazement to humankind, a hymn to our maker.

When I needed to go through the museum to the small wood-paneled room where my father kept his library, so that he might read to me, he would blindfold me so I wouldn’t be shocked by the shelves of curiosities that brought throngs of customers through the doors, especially in the summertime, when the beaches and the grander parks were filled with crowds from Manhattan, who came by carriage and ferry, day-trip steamship or streetcar. But the blindfold my father used was made of thin muslin, and I could see through the fabric if I kept my eyes wide. There before me were the many treasures my father had collected over the years: the hand with eight fingers, the human skull with horns, the preserved remains of a scarlet-colored long-legged bird called a spoonbill, rocks veined with luminous markings that glowed yellow in the dark, as if stars themselves had been trapped inside stone. I was fascinated by all that was strange: the jaw of an ancient elephant called a mastodon and the shoes of a giant found in the mountains of Switzerland. Though these exhibits made my skin prickle with fear, I felt at home among such things. Yet I knew that a life spent inside a museum is not a life like any other. Sometimes I had dreams in which the jars broke and the floor was awash with a murky green mixture of water and salt and formaldehyde. When I woke from such nightmares, the hem of my nightgown would be soaking wet. It made me wonder how far the waking world was from the world of dreams.

My mother died of influenza when I was only an infant, and although I never knew her, whenever I dreamed of terrible, monstrous creatures and awoke shivering and crying in my bed, I wished I had a mother who loved me. I always hoped my father would sing me to sleep, and treat me as if I were a treasure, as valued as the museum exhibits he often paid huge sums to buy, but he was too busy and preoccupied, and I understood his life’s work was what mattered most. I was a dutiful daughter, at least until I reached a certain age. I was not allowed to play with other children, who would not have understood where I lived or how I’d been raised, nor could I go upon the streets of Brooklyn on my own, where there were men who were waiting to molest innocent girls like me.

Long ago what the Indians called Narrioch was a deserted land, used in winter for grazing cattle and horses and oxen. The Dutch referred to it as Konijn Eylandt, Rabbit Island, and had little interest in its sandy shores. Now there were those who said Coney Island had become a vile place, much like Sodom, where people thought only of pleasure. Some communities, like Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach, where the millionaires built their estates, had their own trains with paid conductors to keep out the riffraff. Trains for the masses left from the Brooklyn Bridge Terminal and took little more than half an hour to reach the beachfront communities. The subway was being built, to begin running beneath the East River in 1908, so that more and more throngs would be able to leave the brutal heat of Manhattan in the summertime. The island was a place of contradiction, stretching from the wicked areas where men were alternately entertained and cheated in houses of ill repute and saloons, to the iron pavilions and piers where the great John Philip Sousa had brought his orchestra to play beneath the stars in the year I was born. Coney Island was, above all else, a place of dreams, with amusements like no others, rides that defied the rules of gravity, concerts and games of chance, ballrooms with so many electric lights they glowed as if on fire. It was here that there had once been a hotel in the shape of an elephant, which proudly stood 162 feet high until it burned to the ground, here the world’s first roller coaster, the Switchback Railway, gave birth to more and more elaborate and wilder rides.

The great parks were the Steeplechase and Luna Park, whose star attraction, the famous horse King, dove from a high platform into a pool of water. On Surf Avenue was the aptly named Dreamland, which was being built and would soon rise across the street, so that we could see its towers from our garden path. There were hundreds of other attractions along Surf Avenue, up to Ocean Parkway, so many entertainments I didn’t know how people chose. For me the most beautiful constructions were the carousels, with their magical bejeweled carved animals, many created by Jewish craftsmen from the Ukraine. The El Dorado, which was being installed at the foot of Dreamland Park, was a true amazement, three-tiered and teeming with animals of every sort. My favorites were the tigers, so fierce their green eyes sparked with an inner light, and, of course, the horses with their manes flying out behind them, so real I imagined that if I were ever allowed onto one, I might ride away and never return.

Electricity was everywhere, snaking through Brooklyn, turning night into day. Its power was evident in a showing made by electrocuting a poor elephant named Topsy, who had turned on a cruel, abusive trainer. I was not yet ten whe

n Edison planned to prove that his form of electricity was safe, while declaring that his rival, Westinghouse, had produced something that was a danger to the world. If Westinghouse’s method could kill a pachyderm, what might it do to the common man? I happened to be there on that day, walking home from the market with our housekeeper, Maureen. There was a huge, feverish crowd gathered, all waiting to see the execution, though it was January and the chill was everywhere.

“Keep walking,” Maureen said, not breaking her stride, pulling me along by my arm. She had on a wool coat and a green felt hat, her most prized possession, bought from a famed milliner on Twenty-third Street in Manhattan. She was clearly disgusted by the bloodthirsty atmosphere. “People will disappoint you with their cruelty every time.”

I wasn’t so sure Maureen was right, for there was compassion to be found among the crowd as well. I had spied a girl on a bench with her mother. She was staring at poor Topsy and crying. She appeared to be keeping a vigil, a soulful little angel with a fierce expression. I, myself, did not dare to show my fury or indulge in my true emotions. I wished I might have sat beside this other girl, and held her hand, and had her as my friend, but I was forced away from the dreadful scene. In truth, I never had a friend of my own age, though I longed for one.

All the same, I loved Brooklyn and the magic it contained. The city was my school, for although compulsory education laws had gone into effect in 1894, no one enforced them, and it was easy enough to escape public education. My father, for instance, sent a note to the local school board stating I was disabled, and this was accepted without requirement of any further proof. Coney Island then was my classroom, and it was a wondrous one. The parks were made of papier-mâché, steel, and electricity, and their glow could be seen for miles, as though our city was a fairyland. Another girl in my constrained circumstances might have made a ladder out of strips torn from a quilt, or formed a rope fashioned of her own braided hair so she might let herself out the window and experience the enchantment of the shore. But whenever I had such disobedient thoughts, I would close my eyes and tell myself I was ungrateful. I was convinced that my mother, were she still alive, would be disappointed in me if I failed to do as I was told.

My father’s museum employed a dozen or more living players during the season. Each summer the acts of wonder performed in the exhibition hall several times a day, in the afternoon and in the evenings, each displaying his or her own rare qualities. I was not allowed to speak to them, though I longed to hear the stories of their lives and learn how they came to be in Brooklyn. I was too young, my father said. Children under the age of ten were not allowed inside the museum, owing to their impressionable natures. My father included me in this delicate group. If one of the wonders was to pass I was to lower my eyes, count to fifty, and pretend that person didn’t exist. They came and went over the years, some returning for more seasons, others vanishing without a word. I never got to know the Siamese twins who were mirror images of each other, their complexions veined with pallor, or the man with a pointed head, who drowsed between his performances, or the woman who grew her hair so long she could step on it. They all left before I could speak my first words. My memories were of glances, for such people were never gruesome to me, they were unique and fascinating, and terribly brave in the ways they revealed their most secret selves.

Despite my father’s rules, as I grew older I would peer down from my window in the early mornings, when the employees arrived in the summer light, many wearing cloaks despite the mild weather, to ensure they would not be gawked at, perhaps even beaten, on their way to their employment. My father called them wonders, but to the world they were freaks. They hid their features so that there would be no stones flung, no sheriff’s men called in, no children crying out in terror and surprise. In the streets of New York they were considered abominations, and because there were no laws to protect them, they were often ill used. I hoped that on our porch, beneath the shade of the pear tree, they would find some peace.

My father had come to this country from France. He called himself Professor Sardie, though that was not in fact his name. When I asked what his given name had been, he said it was nobody’s business. We all have secrets, he’d told me often enough, nodding at my gloved hands.

I believed my father to be a wise and brilliant man, as I believed Brooklyn to be a place not unlike heaven, where miracles were wrought. The Professor had principles that others might easily call strange, his own personal philosophy of health and well-being. He had been pulled away from magic by science, which he considered far more wondrous than card tricks and sleight of hand. This was why he had become a collector of the rare and unusual, and why he so strictly oversaw the personal details of our lives. Fish was a part of our daily nourishment, for my father believed that we took on the attributes of our diet, and he made certain I ate a meal of fish every day so my constitution might echo the abilities of these creatures. We bathed in ice water, good for the skin and inner organs. My father had a breathing tube constructed so that I could remain soaking underwater in the claw-foot tub, and soon my baths lasted an hour or more. I had only to take a puff of air in order to remain beneath the surface. I felt comfortable in this element, a sort of girlfish, and soon I didn’t feel the cold as others did, becoming more and more accustomed to temperatures that would chill others to the bone.

In the summer my father and I swam in the sea together each night, braving the waves until November, when the tides became too frigid. Several times we nearly reached Dead Horse Bay, more than five miles away, a far journey for even the most experienced swimmer. We continued an exercise routine all through the winter so that we might increase our breathing capacity, sprinting along the shore. “Superior health calls for superior action,” my father assured me. He believed running would maintain our health and vigor when it was too cold to swim. We trotted along the shore in the evenings, our skins shimmering with sweat, ignoring people in hats and overcoats who laughed at us and shouted out the same half-baked joke over and over again: What are you running from? You, my father would mutter. Fools not worth listening to, he told me.

Sometimes it would snow, but we would run despite the weather, for our regimen was strict. All the same, on snowy nights I would lag behind so I might appreciate the beauty of the beach. I would reach into the snow-dotted water. The frozen shore made me think of diamonds. I was enchanted by these evenings. The ebb and flow at the shore was bone white, asparkle. My breath came out in a fog and rose into the milky sky. Snow fell on my eyelashes, and all of Brooklyn turned white, a world in a globe. Every snowflake that I caught was a miracle unlike any other.

I had long black hair that I wore braided, and I possessed a serious and quiet demeanor. I understood my place in the world and was grateful to be in Brooklyn, my home and the city that Whitman himself had loved so well. I was well spoken and looked older than my age. Because of my serious nature, few would guess I was not yet ten. My father preferred that I wear black, even in the summertime. He told me that in the village in France where he’d grown up, all the girls did so. I suppose my mother, long gone, had dressed in this fashion as a young girl, when my father had first fallen in love with her. Perhaps he was reminded of her when I donned a black dress that resembled the one she wore. I was nothing like my mother, however. I’d been told she was a great beauty, with pale honey-colored hair and a calm disposition. I was dark and plain. When I looked at the ugly twisted cactus my father kept in our parlor, I thought I more likely resembled this plant, with its gray ropy stems. My father swore it bloomed once a year with one glorious blossom, but I was always asleep on those occasions, and I didn’t quite believe him.

Although I was shy, I did have a curious side, even though I had been told a dozen times over that curiosity could be a girl’s ruination. I wondered if I had inherited this single trait from my mother. Our housekeeper, Maureen Higgins, who had all but raised me, had warned me often enough that I should keep my thought

s simple and not ask too many questions or allow my mind to wander. And yet Maureen herself had a dreamy look when she instructed me, which led me to presume that she didn’t follow her own dictates. When Maureen began to allow me to run errands and help with the shopping, I meandered through Brooklyn, as far as Brighton Beach, little over a mile away. I liked to sit by the docks and listen to the fishermen, despite the rough language they used, for they spoke of their travels across the world when I had never even been as far as Manhattan, though it was easy enough to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge or the newer, gleaming Williamsburg Bridge.

Though I had an inquisitive soul, I was always obedient when it came to the Professor’s rules. My father insisted I wear white cotton gloves in the summer and a creamy kid leather pair when the chill set in. I tolerated this rule and did as I was told, even though the gloves felt scratchy on summer days and in winter chafed and left red marks on my skin. My hands had suffered a deformity at birth, and I understood that my father did not wish me to be thought of with the disdain that greeted the living wonders he employed.

Our housekeeper was my only connection to the outside world. An Irish woman of no more than thirty, Maureen had once had a boyfriend who had burned her face with sulfuric acid in a fit of jealous rage. I didn’t care that she was marked by scars. Maureen had seen to my upbringing ever since I was an infant. She’d been my only company, and I adored her, even though I knew my father thought her to be uneducated and not worth speaking to about issues of the mind. He preferred her to wear a gray dress and a white apron, a proper maid’s uniform. My father paid Maureen’s rent in a rooming house near the docks, a cheap and unpleasant place, she always said, that was not for the likes of me. I never knew where she went after washing up our dinner plates, for she was quick to reach for her coat and slip out the door, and I hadn’t the courage to run after her.