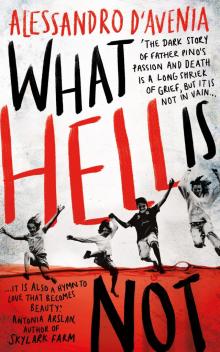

What Hell Is Not

Alessandro D'Avenia

To Marco and Fabrizio,

Brothers who taught me to have fun

and to fight, to speak and to swear . . .

All that is needed for boys to be brothers.

What is hell? I think it is the suffering of one who can no longer love.

(Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, Book 6, Chapter 3)

I believe I am in hell, therefore I am.

(Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell, ‘Night of Hell’)

Contents

Prologue

PART I - A Never-ending Port

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

PART II - Swooning

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Author’s Afterword

By first light, a boy spies her.

She is enveloped in the salty, windy ambush of the virgin dawn as it rises up from the sea only to dive into the semidarkness that pours over the streets.

The boy lives on the top floor of his building. From there, he can see the sea and he can peer into the houses and streets that belong to the men. Up there, he casts his gaze until it loses its bearings. And where the gaze is lost, the heart remains entangled as well. There’s too much sea spread out ahead, especially at night, when the sea vanishes and he can feel the void beneath the stars.

Why is this scene reborn every morning? The boy has no answer. The rose’s withered petals sting more than its thorns and when he looks in the mirror each morning, he sees a castaway. He touches his face and with the sea stuck inside, he looks in his eyes for what still lives. What still lives is her light, glowing on the last day of school. He studies it like the mysterious maps he loved to contemplate as a child hoping to recover treasure and see those islands, ships, and waves.

The boy watches her. She’s the one who rummages through his heart, in the tangle where dreams grow. Things bathed in too much light cast the same amount of shadow. Every light has its grieving. Every port its shipwreck. But boys do not see the shadow. They prefer to ignore it.

He covers his acerbic face with his hands, as if he could feel his visage with his fingers. He resembles a sailor on the pier as he waits for a contract following mandatory shore leave. He continues to watch her. Without end. He allows light, wind, and salt to reshape his flesh and thoughts.

Light, wind, and salt ought to do as they please. Millennia have transformed even the infertile rocks that lie on the edge of the sea. God put a heart in his chest but he forgot to add the armor. He does this with every boy and in this, for every boy, God is cruel.

The boy is seventeen years old and has a life to invent ahead of him. Seventeen holds no promise of good luck. At seventeen, even ugly actors believe they will grow into handsome men. Blood runs hot and when it presses hard against the heart, they are forced to decide what they will make of themselves.

He has all the questions but the answers will arrive only after he has forgotten them. Seventeen is bad timing between supply and demand.

He pinpoints her in the June light and he is scared because this is the last day of school and on that day summer’s escape resides alone in the soul. But he has a thousand questions. Life seems like those textbook equations whose solutions are found in the lower right hand of the page, framed by parentheses. But he never gets the procedure right. And it worries him that two minuses make a plus and a minus and a plus a minus. The minus is always somewhere in between.

Like a siren, all of that sea and all of that light enchant him. And with remission, he allows himself to be ensnared by that enchantment. He looks down from above, as boys his age love to do when they try to solve a maze without entering it. He has no thread to unspool to avoid becoming lost in the pathways of his fears.

What do boys know about becoming men, anyway? What do they know about using the nighttime or its shadows or its darkness? Boys always expect joy out of life. Little do they know that it is life that expects joy out of them. He would like to have a simple life. But life has never been simple. Even though everyone enjoys life, endures life, speaks of life, and writes of life, very little is known of life. Perhaps he is the simple one and he ought to leave his maze of light and grief to life.

Light on the rooftops and grief in the streets, just like a Caravaggio painting. It is the aesthetic paradox of a city inhabited by men and not suitable for spellbound boys. They do not know the pain that it takes to become and how much courage is needed to shake off illusions. The boy knows even less than the others: He has little flesh around his dreams.

For an instant, she stops bewitching and enchaining him. She has eyes to gaze upon him, jealously, with claws to clutch him as voraciously as any siren, as if to reveal the night that he hides jammed in his heart.

His city.

Palermo.

1993.

PART I

A Never-ending Port

Panormus, conca aurea, suos devorat alienos nutrit.

(Palermo, the golden shell that devours her own but feeds strangers.)

(Inscription under the statue of the Genie of Palermo in the Palazzo Pretorio)

The sea is the land’s edge also, the granite,

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation:

The starfish, the horseshoe crab, the whale’s backbone.

(T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets, ‘The Dry Salvages,’ 1.16–19)

Chapter 1

The streets are quiet, despite everything.

With each tenaciously slow puff of the sirocco wind, curtains flap like snakes against the heat-besieged windows. A dog wanders about, trampling oases of

shade. A rare gust of sea breeze tempers the heat. Even the undercurrent is exhausted by the grind.

Don Pino raises the dust with his big shoes. It turns to gold at the touch of all that light. His gait is fast, not because it’s hurried but because it’s slow in a city that was founded on slowness. He approaches his sunbaked, rusty-red Uno. The child is sitting on the hood, his feet dangling beneath him. He’s six years old and has a white t-shirt, soiled shorts, beachcomber sandals, and a mother named Maria at home. She can be tough. End of story.

‘Where are you going at this time of day, Father Pino?’

‘To school.’

‘To do what?’

‘The same thing that you do.’

‘To give my classmates a beating?’

‘No, to learn.’

‘But you’re a grownup. What do you need to learn?’

‘The more you know, the more you need to learn . . . You’re not going to school today?’

‘School’s out for summer.’

‘Are you sure? Today’s the last day of school. But there is class today. Otherwise, yesterday would have been the last day.’

‘School’s over when you decide it’s over.’

‘Since when?’

‘Damn, you ask some tough questions!’

‘What are you doing here?’

‘Waiting.’

‘For what?’

‘Nothing.’

‘What do you mean, “nothing”?’

‘Why do I have to be waiting for something?’

‘How about this?’ he asks as he gives the boy a pat on the cheek.

‘Is your school a school for big kids?’

‘Yes, it is. Sixteen-, seventeen-, and eighteen-year-olds.’

‘And what do they learn them?’

‘They are taught, not learned. They study things that big kids study.’

‘I learn myself things like that.’

‘In this case you say, “I learn them myself.” ’

‘Damn, what a pain in the neck! Teach, learn. It’s all the same.’

‘Well, you’re right about that.’

‘So what do they learn?’

‘Italian, philosophy, chemistry, math . . .’

‘What are you gonna do there?’

‘You get to know the secrets behind things and people.’

‘We have Rosalia for that.’

‘Who’s that?’

‘The hairdresser.’

‘No, no. At school, you learn secrets that even she doesn’t know.’

‘I don’t believe it.’

‘Too bad for you.’

‘Well, tell me a secret.’

‘Do you know what “Francesco” means?’

‘I know it’s my name. That’s it.’

‘Yes, that’s true. It’s a name. But it’s an ancient name. It was used for people who descended from the Franks.’

‘Who were they?’

‘They lived during the time of Charlemagne.’

‘And who was he?’

‘Francesco, when is this going to end? The Franks were called Franks because they were free. Frank means free. Francesco means a man who is free.’

‘And what’s that supposed to mean?’

‘I’ll tell you another time.’

‘So what do you learn them?’

‘ “I teach them” is the proper way to say it. I teach them religion.’

‘What does religion have to do with it?’

‘Religion teaches you the most important secret of all.’

‘How to steal something and never get caught?’

‘No.’

‘Then what?’

‘If I told you, it wouldn’t be a secret.’

‘I’m no snitch. I won’t tell a soul.’

‘That has nothing to do with it. It’s a secret that’s hard to understand.’

‘I’m going to be seven soon. I can understand just about anything!’

‘Someday I’ll tell you the secret.’

‘Do you promise?’

‘I promise.’

‘Do you perform miracles?’

‘No, I’m too small for that.’

‘But you’re, like, 150,000 years old!’

‘Fifty-five years old.’

‘But isn’t that more than 100,000?’

‘Watch it, kid. Who do you think you are?’

‘But if you’re so small, why do you have such big feet?’

‘To walk far and get to the people who need me.’

‘And what about those ears? They’re huge, Don Pino!’

‘They let me listen more and talk less.’

‘You have really big hands, too . . .’

‘I just can’t get anything past you, can I?’

Don Pino smiles, puts his hand on the boy’s head, and messes up his red, Norman hair. It’s just like those blue eyes: Uncut diamonds that the Nordic peoples mounted on the Arabs’ dark skin after they had snatched up their cities.

Francesco smiles. And his eyes sparkle like magic. History is layered in those eyes.

‘Damn, you know so many things, Don Pino.’

‘Come on. I’ve got to get going. Otherwise, I’m going to be late.’

‘But you’re always late, Don Pino.’

‘Look who’s talking!’

‘And why the bald head? Why is your head so smooth?’

Don Pino pretends to give him a kick in the butt and starts laughing.

‘Do you see how beautiful the sunshine is here in Palermo?’

‘But we’re not in Palermo! We’re in Brancaccio!’

‘Fine. It’s the same difference. My bald head helps to reflect the sunlight so that people can see better.’

He bends over to show him up close and Francesco places his hand on his head.

‘Damn, you have a hard head, Don Pino!’

‘It’s for breaking through the thickest of walls,’ says Don Pino, grinning like a boy as he speaks. A small boy, like a seed in the ground, like flower seed that his mother used to keep on her balcony, like the lumps of yeast that she used to put into the bread dough.

‘Would you be my daddy, Don Pino?’ says Francesco.

‘What on earth are you talking about?’

‘Well, I only have my mother. I don’t know where my father is. It’s a mystery. Maybe you know the answer since you know so many things that are hard to understand.’

‘No, Francesco, I don’t.’

Don Pino fumbles for his keys in his pocket but they wriggle free like fish caught in a net that’s been hoisted aboard a fishing boat.

Francesco looks down at the ground, motionless.

Don Pino finally finds his keys and starts to open the door. But Francesco doesn’t budge. Don Pino leans over so that he can look him in the eye.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asks him.

‘Everyone calls you “father.” But you don’t want to be my dad even though I don’t have a dad.’

‘That’s true. But I’m not your father.’

‘Then why does everyone call you “Father Pino”? Do you know why?’

‘Well . . . because . . . It’s a figure of speech.’

‘You’re a father and you belong to the Church. But aren’t there some fathers that don’t belong to the Church?’

Don Pino stands there in silence.

‘Come on, Francesco. Let’s just say there’s some truth to what you’re saying.’

He takes him by the hand and the child gets down from the hood of the car and smiles.

Don Pino smiles, too. He gets in the car and makes the sign of the horns.

‘You’ve got horns! Pointy ones!’ says Don Pino.

‘So that I can break the ‘‘thickest walls’’ just like you.’

Francesco closes the door and sticks his tongue out at Don Pino.

Don Pino pretends to be angry and he starts to drive off.

But the child knocks on the window with a worried look on his face

.

Don Pino rolls down the window.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asks.

‘When you perform a miracle, do you promise you’ll tell me?’

‘I promise.’

‘But it needs to be a big one, like making it snow in Brancaccio.’

‘Snow in Brancaccio? You’re asking the impossible.’

‘I’ve only ever seen snow in cartoons. What kind of a priest are you, anyway?’

‘Okay, sure.’

‘Ciao, Father.’

‘Ciao, Francesco.’

As he drives away, Don Pino looks in the mirror and sees a somber face.

He can feel those kids kicking in his heart like babies in their mother’s womb. One of these days, they’ll rip that little heart of his right out of his chest. And who knows how much time he has left? Who will take care of Francesco and all the rest of them? Who will take care of Maria, Riccardo, Lucia, Totò . . .?

He’s run out of time. There’s no time left yet there are all those kids, just like seeds scattered in a field. The thorns wish to choke them. Hungry crows wish to devour them.

The train crossing’s barrier has been lowered. The train crossing that separates Brancaccio from Palermo like a ghetto. A little girl stands beyond the barrier on the other side of the tracks. She looks out toward the arriving train. She leans over as if there were a line that she shouldn’t cross. A doll dangles upside down in her hand.

Before Don Pino can get out of his car, the train bolts by him and swallows up the girl. Her hair goes wild in the suction of the train cars. She focuses on them like film unspooling at the movies. Her imagination follows that train as her thoughts are filled with every possible destination. She would like to get on it, with her doll, so that she can take it far away. She doesn’t know where the trains go but she knows they go far. Just like the ships that go behind the sea. Who knows where they end up? This is the reason that the only thing she enjoys more in the world than her doll is when her father teaches her how to swim. So that she can go see what’s behind the sea.

She disappears with the last train car. Don Pino stands motionless halfway between the barrier and the car door, looking at a mirage. He doesn’t know who that girl is. He knows only that he saw her fly away toward a train with her colored dress, out of reach. What if she had been run over?

The barrier rises up again. Don Pino slowly gets back in his car, looking for any signs of her presence. And as if on cue, a car horn starts honking. Where could they be going in such a hurry in a city where parking is a mere aspiration?