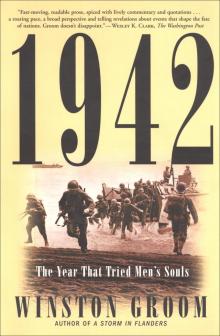

1942: The Year That Tried Men's Souls

Winston Groom

Also by Winston Groom

Better Times Than These

As Summers Die

Only

Conversations with the Enemy (with Duncan Spencer)

Forrest Gump

Shrouds of Glory

Gone the Sun

Gumpisms

Gump & Co.

Such a Pretty, Pretty Girl

The Crimson Tide

A Storm in Flanders

1942

The Year that Tried Men’s Souls

Winston Groom

Copyright © 2005 by Winston Groom

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Every effort was made to secure permissions for photographs and text. Please contact the publisher if you have information regarding permissions.

“The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” and excerpt from “Losses” from The Complete Poems by Randall Jarrell. Copyright © 1969, renewed 1997 by Mary von S. Jarrell. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpts from Death March: The Survivors ofBataan, copyright © 1981 by Donald Knox, reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Inc.

All interior photographs courtesy of the National Archives except for photo of Cat Island, Mississippi, courtesy of Inga Coates-Boyea on behalf of Robert Coates.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Groom, Winston, 1944–

1942 : the year that tried men’s souls / Winston Groom.

p. cm.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4778-4

1. World War, 1939-1945. I. Title.

D755.4.G76 2005

940.53—dc22 2004062779

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

In memory of my parents, both of whom did their part when their nation called

“The Axis knew that they must win the war in 1942 or lose everything.”

—Franklin Delano Roosevelt, State of the Union speech, January 6, 1943

“Now, this is not the end, it is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

—Winston Churchill, November 10, 1942

Foreword

To the generation of Americans who lived through it, the Second World War was the defining event of the twentieth century, much as the Civil War had been eighty years earlier. Those born in the first part of the century who came of age in the 1930s and ’40s routinely began to describe almost every event and memory of their lives as having occurred “before the war,” “during the war,” or “after the war.”

It was the most dangerous and deadly conflict ever inflicted on the planet. At stake was the fate of the world. If the war had been lost to the Axis powers, modern civilization would have fallen under the sway of cruel tyrants and the world perhaps subjected to another forty generations of darkness, as it was after the barbarians conquered the Roman empire. No nation was safe from the evil, whether it chose to be neutral or not; it was spreading like a cancer across the world.

Twenty years earlier a savage four-year-long war had been fought in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East between the Western democracies, Russia, and the German–Austria-Hungarian empires over control of those same areas. The Germans lost and were subjected to a harsh peace. This was the Great War, and, in the hopeful eyes of many, the War to End all Wars. Later it became known as the world war but, finally, just the First World War, to distinguish it from what came later.

The truce of 1918, followed by the peace of 1919, did not last long. Whereas the rulers of Germany in 1914 and her allies who provoked World War I were—to use the term in its most generous sense—at least “gentlemen,” the leaders of the Axis powers in 1941 were thugs. They were, most of them, amoral murderers and brutish torturers who gained power through assassination and corruption, and more than sixty years after the fact this remains a stubborn truth.

That is not to say that America, Great Britain, and the other Allied nations were always on the side of the angels. Joseph Stalin in his totalitarian Soviet Union was certainly a great monster, as the Russian people finally now can, and will, freely admit. But war often makes strange bedfellows, and the Western democracies’ alliance with the Soviet communists, however expedient or necessary, was among the strangest.

If the Second World War defined the twentieth century, then the year 1942 can be understood as having defined the war itself. It was the most perilous of times; for the United States and its allies, the first six months of that year saw a relentless flood of military disasters with the Axis almost everywhere victorious—especially in the Pacific, where Imperial Japan conquered territory after territory, despite the most strenuous efforts to stop them. In the minds of many Americans the final outcome of the war was in doubt.

Into this roiling, fearful, fateful year I was conceived, as were many others of the so-called war-babies generation. I was not born into a family of warriors, although practically every generation of it has served in one American war or another, from the War of Independence and the War of 1812, to the Creek Indian wars and the Civil War, to the Spanish-American War and the First World War.

Now came my father’s turn. Like many young men of his day he was a member of the National Guard, an institution that each of the states maintains under federal guidance and law to keep the peace and, more important, provide the structure for a responsive army in case of a national emergency. This emergency soon came as war clouds gathered over Europe and the Pacific, and practically all national guardsmen found themselves on the front lines during the first year of the war.

The National Guard was both a social and a military organization in most southern states, and in my home state of Alabama this was certainly the case. Fine dinners and balls were held in the Fort Whiting National Guard Armory, an imposing three-story white stone structure alongside Mobile Bay. In faded photograph albums there are pictures of my father, escorting my mother, soon to be his fiancee, in his dress uniform, complete with sword and formal military regalia. But of course there was also the serious side, and as war broke out with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, my father was ordered to Fort Riley, Kansas, with, of all things, a regiment of horse cavalry.

These “horse soldiers” were already an anachronism, but in the military services traditions die hard, and so my father, then thirty-six years old, found himself at the reins of a large animal on the plains of Kansas, practicing tactics and maneuvers long rendered archaic by the evolution of modern warfare. Not long afterward his bemusement was relieved when somebody at headquarters discovered that he was, by trade, an attorney, and as the U.S. War Department had almost completed an enormous structure in Arlington, Virginia, known as the Pentagon* he was requested to report there and assume lawyerly duties as a captain in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

It was in the little military chapel at nearby Fort Myer, Virginia, that my parents were wed, in 1942, and there, at Garfield Hospital acr

oss the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., that I was born the following year. My father’s side of the family was American by many generations but my mother’s was first-generation Norwegian. Her father, Mathias Knudsen, my grandfather, came here in 1899 as a ship’s captain with the United Fruit Company. While in Washington my mother worked tirelessly with the Norwegian embassy (then in exile) raising funds for that beleagured country of her parent’s heritage. Today on a wall in my study is an elaborate thank-you proclamation in her honor from the King of Norway, whose son, King Olaf IV, once paid a personal visit to our family twenty-odd years later. The note begins: “Dear Mrs. Knudsen Groom, His Majesty the King of Norway wishes to thank you ...” And so that complex mix of Americans served however they could.

As the years passed and the war ended and I grew older I clearly remember sitting at large family dinners where my father, mother, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and guests spoke the far-off language of adults, the sentences of which were almost always preceded by “Before the war . . .,” “During the war . . .,” and “After the war ...” But to me and to my cousins and friends, in truth, the war was something that had happened long ago, to a different generation, their generation, in different, distant times.*

Later, at school, we got a smattering of the war’s history and import. Since mine was a military school, we probably got more of a smattering than most, but it was covered generally in the courses on United States history, and probably more was discussed about the American Civil War than World War II. Still later, in college, I had my most meaningful acquaintance with the magnitude of the world war. I had decided to take a summer correspondence course after my junior year in order to be less fettered with academic concerns during my final year, which I had intended to spend in splendid debauchery. To that end I selected a subject called “United States Naval History,” which I thought would be both easy and fun. It was neither. It was without qualification the hardest course I ever took in college and, despite the fact that one could use any text available and write from it, I almost failed the thing. (In the end I pulled out a low “B.”)

The professor at the university who taught this intellectually demanding (I could use the word “cruel”) subject had been a naval officer in the Pacific during the war. His texts were Sea Power by Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Two-Ocean War by Samuel Eliot Morison, and The Great Sea War by Admiral Chester Nimitz and E. B. Potter. It was then that I began to understand the enormity and perils of the war, especially in the Pacific during 1942, and the suffering and sacrifices that attended it. I learned in detail of the disaster at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, a sneak attack on America by a band of fanatically religious emperor-worshipers who became the first to practice suicide airplane attacks.* I was astonished by the fantastic lack of preparedness and foresight that caused the loss of the Philippines along with General Douglas MacArthur’s entire 120,000-man army, by the wreckage of the American Pacific and Far East fleets and the week-by-week Japanese conquests of nearly all of the Pacific Ocean territory from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska to the Australian continent in the South Seas.

Born when I was, it was my luck good or bad to come of military age just as the Vietnam War reached its most pitiless intensity and, having served there, I began to take an interest in wars and warfare for it seemed to me even at that younger age that this would be, regrettably, a permanent condition of mankind, at least in my time, and, more or less, I have been writing about war ever since. Over the years this has led to an evident conclusion: that most wars, like all great dramas, have a single, seminal act that defines the future course of events. During the Second World War, that act was played out in the menacing year of 1942.

After the barbarous attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, it was easy to recollect that the tale of America in 1942 also began as one of shock, uncertainty, and fear, beginning with Pearl Harbor. Even though 1942 ended in triumph over Axis expansion, to most people that triumph was only partially clear at the time; anyone with a brain knew there was a long, bitter, and uncertain fight ahead, until these powerful enemies were contracted back from whence they had come.

One expects this will be so, too, with the present war against international terrorism—a world war in every sense of the word—and one point of this story is to recall for the reader what Americans can do when they get mad and set their minds to something. Terrorist organizations have been in existence at least since the mid-1800s, no doubt even earlier, throwing bombs and gunning down symbols of the power they have resented, mainly European royalty, aristocracy, and its representatives. In those days they were called anarchists, and they even bombed Wall Street and the New York Stock Exchange; for that matter, a terrorist act actually touched off World War I. The important difference in present times is the firepower modern terrorists can bring to bear, their relentless religious fervor, and their callous disregard for innocent civilians and even their own lives.

While I have tried to bring as much fresh material as possible to this tale of tragedy and triumph in the year 1942, some of the stories will be familiar, perhaps even old hat to those who devour every scrap of detail about the Second World War. While I hope they will enjoy it too, it is not for them that I write but to the average American reader, in hopes that he or she will take renewed pride in what our forefathers dealt with, and determined to accomplish, when faced with danger of the utmost severity. The focus of this story is on the American ordeal during 1942, its tragedy and triumph, and those of the ally it fought with so closely then, Great Britain; I have not gone into extensive detail to catalogue the heroic fight of the Soviet Union during this time because it would require a separate book to do it justice.

Following the Pearl Harbor disaster, America was in grave military danger. Most of our Pacific fleet and air force no longer existed and the Japanese were running amok all over that ocean and in the Far East, banging at the very gates of Australia and India and even invading U.S. territory in Alaska. America was almost totally unprepared for war and would not be fully equipped for another year. By a wide margin she was losing the battle of the Atlantic to German submarines, and the U.S. fighting forces were nowhere near to being properly trained and ready to fight. That they did so anyway—so that by the end of 1942 the worldwide Axis onrush was blunted for good—should be considered nothing less than awe-inspiring.

Chapter One

World War II descended on planet earth as swift and deadly as a desert whirlwind, but the forces that unleashed its terrible power had been building beyond the horizon for years. Whole libraries exist to house only the books that grapple with the roots and causes but, as most wars do, it boils down to three simple things: pride, property, and power—and two more complicated things: prejudice and persecution. With this in mind I believe it is useful for readers of this story to have an appreciation, however abbreviated, of the events leading up to the critical year of 1942, and in that spirit a concise narration is offered.

Germany’s role of instigating the conflict is better understood than that of the Japanese. The Nazi militarists had arisen bitter and venomous from the bones and ashes of the First World War, convinced that they had been stabbed in the back by their own cowardly politicians and the Jews—these latter perceived as either communists (the poorer ones) or war profiteers (the rich). Added to that was the loathing that practically all Germans felt over the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, which the Allied Powers, principally France and England, imposed upon Germany following the armistice of 1918. Among other things, this document stripped the Germans of 25,000 square miles of their territory, which included vast amounts of its raw materials such as coal, ores, and oil, as well as all of its overseas colonies and practically all of its military armaments. Most gallingly, it required the German people to pay “war reparations” to the victors to the tune of many billions of dollars. Germany struggled under these conditions, plagued by labor strikes (ultimately, so they claimed, forced on them by the Jews) and othe

r internal strife, for the next ten years.

Then in 1929 the American stock market crashed, setting into motion a worldwide economic depression. In Germany, monetary inflation at one point reached such stupendous proportions that a mere loaf of bread cost a million or more German marks! At the normal ratio of four marks to the dollar, this was devastating, and many Germans saw their life’s savings wiped out almost overnight.*

Finally there was the matter of German honor. Up until the very moment in 1918 when the Germans sought an armistice, that nation’s people were persuaded by its leaders and the press to believe that they were only a few footsteps away from total victory. News of their defeat came as an unbelievable shock. This was where the stabbed-in-the-back theory came into play. The American army had arrived on the scene in force just six months before the cease-fire was requested by Germany, but the American commander in chief, General John J. Pershing, was all for marching into Berlin anyway, herding the German army before him with all of its soldiers’ hands in the air.1

This was the only way, Pershing declared, that the German people would believe they had been beaten. But France and Britain, exhausted by four years of slaughter in the trenches of the Western Front, disagreed about further military action, and their view prevailed. Thus the Germans increasingly came to think that they had not been beaten at all, but had been betrayed by dishonorable politicians (backed by Jews) who gave up the fight before victory could be won. Humiliation is a stern taskmaster, and the Germans had long memories. Thus some historians, and many others, are of the opinion that the Second World War was merely an extension of the First World War, with a twenty-year “rest period” in between.

Into this combustible mix entered Adolf Hitler, a cranky aspiring Austrian artist who had served as a corporal in the German army from 1914 to 1918. Having been decorated with the Iron Cross, Hitler emerged from the First World War even more bitter than most of the rest of his adopted countrymen. By 1922 he had assembled about him a clique of like-minded people who called themselves Nazis (National Socialist Party) and who distributed pamphlets such as Bolshevismfrom Moses to Lenin, which attempted to prove that “Judaism was the great destructive force which had ruined Western Civilization.”2 Psychiatrists have diagnosed Hitler’s case history as that of a “psychopathic escapist type with a complex effecting megalomania.” Historians smugly described him as someone who had “escaped from his case history into world history, before the psychiatrists got him.”3