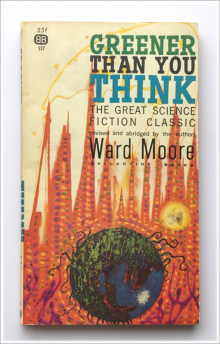

Greener Than You Think

Ward Moore

Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

GREENER THAN YOU THINK

Also by WARD MOORE

_Breathe the Air Again_

WARD MOORE

_Greener Than You Think_

WILLIAM SLOANE ASSOCIATES, INC. _Publishers_ ....... _New York_

Copyright, 1947, by WARD MOORE

_First Edition_

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES

Transcriber's Note:

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed. The text intentionally contains non-standard contractions, unhyphenated combination words and other informal styles and spellings, which, except for minor typographical errors, have all been transcribed as printed.

_For_ BECKY 1927-1937

"... I knew there was but one way; for his nose was as sharp as a pen, and 'a babbled of green fields. 'How now, Sir John!' quoth I; 'what, man! be o' good cheer.' So 'a cried out, 'God, God, God!' three or four times. Now I, to comfort him, bid him 'a should not think of God; I hop'd there was no need to trouble himself with any such thoughts yet...." _Henry V_

_One:_ Albert Weener Begins 1

_Two:_ Consequences of a Discovery 47

_Three:_ Man Triumphant I 99

_Four:_ Man Triumphant II 159

_Five:_ The South Pacific Sailing Discovery 255

_Six:_ Mr Weener Sees It Through 327

Neither the vegetation nor people in this book are entirely fictitious.But, reader, no person pictured here is you. With one exception. You,Sir, Miss, or Madam--whatever your country or station--are AlbertWeener. As I am Albert Weener.

ONE

_Albert Weener Begins_

_1._ I always knew I should write a book. Something to help tired mindslay aside the cares of the day. But I always say you never can tellwhat's around the corner till you turn it, and everyone has become soaccustomed to fantastic occurrences in the last twenty one years thatthe inspiring and relaxing novel I used to dream about would be today asunreal as Atlantis. Instead, I find I must write of the things whichhave happened to me in that time.

It all began with the word itself.

"Grass. Gramina. The family Gramineae. Grasses."

"Oh," I responded doubtfully. The picture in my mind was only of a vaguearea in parks edged with benches for the idle.

Anyway, I was far too resentful to pay strict attention. I had set outin good faith, not for the first time in my career as a salesman, toanswer an ad offering "$50 or more daily to top producers," naturallyexpecting the searching onceover of an alert salesmanager, back to thelight, behind a shinytopped desk. When youve handled as many products asI had an ad like that has the right sound. But the world is full ofcrackpots and some of the most pernicious are those who hoodwinkunsuspecting canvassers into anticipating a sizzling deal where there isactually only a warm hope. No genuinely highclass proposition ever camefrom a layout without aggressiveness enough to put on some kind offront; working out of an office, for instance, not an outdated, rundownapartment in the wrong part of Hollywood.

"It's only a temporary drawback, Weener, which restricts theMetamorphizer's efficacy to grasses."

The wheeling syllables, coming in a deep voice from the middleagedwoman, emphasized the absurdity of the whole business. The snuffyapartment, the unhomelike livingroom--dust and books its onlyfurniture--the unbelievable kitchen, looking like a pictured warning tohousewives, were only guffaws before the final buffoonery of discoveringthe J S Francis who'd inserted that promising ad to be Josephine SpencerFrancis. Wrong location, wrong atmosphere, wrong gender.

Now I'm not the sort of man who would restrict women to a place in thenursery. No indeed, I believe they are in some ways just as capable as Iam. If Miss Francis had been one of those wellgroomed, efficient ladieswho have earned their place in the business world without at the sametime sacrificing femininity, I'm sure I would not have suffered such apang for my lost time and carfare.

But wellgroomed and feminine were alike inapplicable adjectives.Towering above me--she was at least five foot ten while I am of averageheight--she strode up and down the kitchen which apparently was officeand laboratory also, waving her arms, speaking too exuberantly, theantithesis of moderation and restraint. She was an aggregate ofcylinders, big and small. Her shapeless legs were columns with largeflatheeled shoes for their bases, supporting the inverted pediment ofgreat hips. Her too short, greasespotted skirt was a mighty barrel andon it was placed the tremendous drum of her torso.

"A little more work," she rumbled, "a few interesting problems solved,and the Metamorphizer will change the basic structure of any plantinoculated with it."

Large as she was, her face and head were disproportionately big. Hereyes I can only speak of as enormous. I dare say there are some whowould have called them beautiful. In moments of intensity they boredinto mine and held them till I felt quite uncomfortable.

"Think of what this discovery means," she urged me. "Think of it,Weener. Plants will be capable of making use of anything within reach.Understand, Weener, anything. Rocks, quartz, decomposedgranite--anything."

She took a gold victorian toothpick from the pocket of her mannishjacket and used it energetically. I shuddered. "Unfortunately," she wenton, a little indistinctly, "unfortunately, I lack resources for furtherexperiment right now--"

This too, I thought despairingly. A slight cash investment--just enoughto get production started--how many wishful times Ive heard it. I was asalesman, not a sucker, and anyway I was for the moment without liquidcapital.

"It will change the face of the world, Weener. No more usedup areas, nomore frantic scrabbling for the few bits of naturally rich ground, nomore struggle to get artificial fertilizers to wornout soil in the faceof ignorance and poverty."

She thrust out a hand--surprisingly finely and economically molded,barely missing a piledup heap of dishes crowned by a flowerpot trailingdroopy tendrils. Excitedly she paced the floor largely taken up by jarsand flats of vegetation, some green and flourishing, others gray andsickly, all constricting her movements as did the stove supporting aglass tank, robbed of the goldfish which should rightfully have gapedagainst its sides and containing instead some slimy growth topped by abubbling brown scum. I simply couldnt understand how any woman could sofar oppose what must have been her natural instinct as to live and workin such a slatternly place. It wasnt just her kitchen which wasdisordered and dirty; her person too was slovenly and possibly unclean.The lank gray hair swishing about her ears was dark, perhaps from vigor,but more likely from frugality with soap and water. Her massive,heavychinned face was untouched by makeup and suggested an equalinnocence of other attentions.

"Fertilizers! Poo! Expedients, Weener--miserable, makeshift expedients!"Her unavoidable eyes bit into mine. "What is a fertilizer? A tidbit, apap, a lollypop. Indians use fish; Chinese, nightsoil; agriculturalchemists concoct tasty tonics of nitrogen and potash--where's yourprogress? Putting a mechanical whip on a buggy instead of inventing aninternal combustion engine. Ive gone directly to the heart of thematter. Like Watt. Like Maxwell. Like Almroth Wright. No use being heldback because youve only poor materials to work with--leap ahead withimagination. Change the plant itself, Weener, change the plant itself!"

It was no longer politeness which held me. If I could have freed myselffrom her eyes I would have escaped thankfully.

"Nourish'm on anything," she

shouted, rubbing the round end of thetoothpick vigorously into her ear. "Sow a barren waste, a worthlessslagheap with lifegiving corn or wheat, inoculate the plants with theMetamorphizer--and you have a crop fatter than Iowa's or the Ukraine'sbest. The whole world will teem with abundance."

Perhaps--but what was the sales angle? Where did I come in? I didnt knowa dandelion from a toadstool and was quite content to keep my distancefrom nature. Had she inserted the ad merely to lure a listener? Herwhole procedure was irregular: not a word about territories andcommissions. If I could bring her to the point of mentioning thenecessary investment, maybe I could get away gracefully. "You said youwere stuck," I prompted, resolved to get the painful interview overwith.

"Stuck? Stuck? Oh--money to perfect the Metamorphizer. Luckily it willdo it itself."

"I don't catch."

"Look about you--what do you see?"

I glanced around and started to say, a measuring glass on a dirty platenext to half a cold fried egg, but she stopped me with a sweep of herarm which came dangerously close to the flasks and retorts--all holdingdirtycolored liquids--which cluttered the sink. "No, no. I meanoutside."

I couldnt see outside, because instead of a window I was facing a sicklyleaf unaccountably preserved in a jar of alcohol. I said nothing.

"Metaphorically, of course. Wheatfields. Acres and acres of wheat.Bread, wheat, a grass. And cornfields. Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois--not astate in the Union without corn. Milo, oats, sorghum, rye--all grasses.And the Metamorphizer will work on all of them."

I'm always a man with an open mind. She might--it was just possible--shemight have something afterall. But could I work with her? Go out in thesticks and talk to farmers; learn to sit on fence rails and whittle,asking after crops as if they were of interest to me? No, no ... it wasfantastic, out of the question.

A different, more practical setup now.... At least there would have beenno lack of prospects, if you wanted to go miles from civilization tofind them; no answers like We never read magazines, thank you. Of courseit was hardly believable a woman without interest in keeping herselfpresentable could invent any such fabulous product, but there was a barechance of making a few sales just on the idea.

The idea. It suddenly struck me she had the whole thing backwards.Grasses, she said, and went on about wheat and corn and going out to therubes. Southern California was dotted with lawns, wasnt it? Why rusharound to the hinterland when there was a big territory next door? Andundoubtedly a better one?

"Revive your old tired lawn," I improvised. "No manures, fuss, cuss, ormuss. One shot of the Meta--one shot of Francis' Amazing Discovery andyour lawn springs to new life."

"Lawns? Nonsense!" she snorted, rudely, I thought. "Do you think Ivespent years in order to satisfy suburban vanity? Lawns indeed!"

"Lawns indeed, Miss Francis," I retorted with some spirit. "I'm asalesman and I know something about marketing a product. Yours should besold to householders for their lawns."

"Should it? Well, I say it shouldnt. Listen to me: there are two ways ofmaking a discovery. One is to cut off a cat's hindleg. The discovery isthen made that a cat with one leg cut off has three legs. Hah!

"The other way is to find out your need and then search for a method offilling it. My work is with plants. I don't take a daisy and see if Ican make it produce a red and black petaled monstrosity. If I did I'd bea fashionable horticulturist, delighted to encourage imbeciles to growgrass in a desert.

"My method is the second one. I want no more backward countries; no morefamines in India or China; no more dustbowls; no more wars, depressions,hungry children. For this I produced the Metamorphizer--to make not twoblades of grass grow where one sprouted before, but whole fieldsflourish where only rocks and sandpiles lay.

"No, Weener, it won't do--I can't trade in my vision as a downpayment ona means to encourage a waste of ground, seed and water. You may think Ilost such rights when I thought up the name Metamorphizer to appeal onthe popular level, but there's a difference."

That was a clincher. Anyone who believed Metamorphizer had salesappealjust wasnt all there. But why should I disillusion her and wound herpride? Down underneath her rough exterior I supposed she could be assensitive as I; and I hope I am not without chivalry.

I said nothing, but of course her interdiction of the only possibilitykilled any weakening inclination. And yet ... yet.... Afterall, I had tohave _something_....

"All right, Weener. This pump--" she produced miraculously from thejumble an unwieldy engine dragging a long and tangling tail of hosebehind it, the end lost among mementos of unfinished meals "--this pumpis full of the Metamorphizer, enough to inoculate a hundred and fiftyacres when added in proper proportion to the irrigating water. I have atable worked out to show you about that. The tank holds five gallons;get $50 a gallon--a dollar and a half an acre and keep ten percent foryourself. Be sure to return the pump every night."

I had to say for her that when she got down to business she didnt wasteany words. Perhaps this contrasting directness so startled me I wasroped in before I could refuse. On the other hand, of course, I would behelping out someone who needed my assistance badly, since she couldnt,with all the obvious factors against her, be having a very easy time.Sometimes it is advisable to temper business judgment with kindness.

Her first offer was ridiculous in its assumption that a salesman'stalent, skill and effort were worth only a miserable ten percent, asthough I were a literary agent with something a cinch to sell. I beganto feel more at home as we ironed out the details and I brought theknowledge acquired with much hard work and painful experience into thebargaining. Fifty percent I wanted and fifty percent I finally got bydemanding seventyfive. She became as interested in the contest as shehad been before in benefits to humanity and I perceived a keen mindunder all her eccentricity.

I can't truthfully say I got to like her, but I reconciled myself andeventually was on my way with the pump--a trifling weight to MissFrancis, judging by the way she handled it, but uncomfortably heavy tome--strapped to my back and ten feet of recalcitrant hose coiled roundmy shoulder. She turned her imperious eyes on me again and repeated forthe fourth or fifth time the instructions for applying, as though I wereless intelligent than she. I went out through the barren livingroom andtook a backward glance at the scaling stucco walls of theapartmenthouse, shaking my head. It was a queer place for Albert Weener,the crackerjack salesman who had once led his team in a national contestto put over a threepiece aluminum deal, to be working out of. And for awoman. And for such a woman....

_2._ Everything is for the best, is my philosophy and Make your crossyour crutch is a good thought to hold; so I reminded myself that ittakes fewer muscles to smile than to frown and no one sees the brightside of things if he wears dark glasses. Since it takes all kinds tomake a world and Josephine Spencer Francis was one of those kinds, wasntit only reasonable to suppose there were other kinds who would buy thestuff she'd invented? The only way to sell something is first to sellyourself and I piously went over the virtues of the Metamorphizer in mymind. What if by its very nature there could be no repeat business? Iwasnt tying myself to it for life.

All that remained was to find myself a customer. I tried to recall thelocation of the nearest rural territory. San Fernando valley,probably--a long, tiresome trip. And expensive, unless I wished todemean myself by thumbing rides--a difficult thing to do, burdened as Iwas by the pump. If she hadnt balked unreasonably about putting thestuff on lawns, I'd have prospects right at hand.

I was suddenly lawnconscious. There was probably not a Los Angelesstreet I hadnt covered at some time--magazines, vacuums, old gold,nearnylons--and I must have been aware of green spaces beforemost of the houses, but now for the first time I saw lawns. Neat,sharply confined, smoothshaven lawns. Sagging, slipping,eager-to-keep-up-appearances but fighting-a-losing-game lawns. Ragged,weedy, dissolute lawns. Halfbare, repulsively crippled, hummocky lawns.Bright lawns, insistent on former respectability and trimness; yellowand gray lawns, touche

d with the craziness of age, quite beyond allinterest in looks, content to doze easily in the sun. If Miss Francis'mixture was on the upandup and she hadnt introduced a perfectlyunreasonable condition--why, I couldnt miss.

On the other hand, I thought suddenly, I'm the salesman, not she. It wasup to me as a practical man to determine where and how I could sell tothe best advantage. With sudden resolution I walked over a twinklinggreensward and rang the bell.

"Good afternoon, madam. I can see from your garden youre a lady who'sinterested in keeping it lovely."

"Not my garden and Mrs Smith's not home." The door shut. Not gently.

The next house had no lawn at all, but was fronted with a rank growth ofivy. I felt no one had a right to plant ivy when I was selling somethingeffective only on the family Gramineae. I tramped over the ivy hard andrang the doorbell on the other side.

"Good afternoon, madam. I can see from the appearance of your lawn yourea lady who really cares for her garden. I'm introducing to a restrictedgroup--just one or two in each neighborhood--a new preparation, anastounding discovery by a renowned scientist which will make your grasstwice as green and many times as vigorous upon one application, withoutthe aid of anything else, natural or artificial."

"My gardener takes care of all that."

"But, madam--"

"There is a city ordinance against unlicensed solicitors. Have you alicense, young man?"

After the fifth refusal I began to think less unkindly of Miss Francis'idea of selling the stuff to farmers and to wonder what was wrong withmy technique. After some understandable hesitation--for I don't make apractice of being odd or conspicuous--I sat down on the curb to think.Besides, the pump was getting wearisomely heavy. I couldnt decideexactly what was unsatisfactory in my routine. The stuff had neitherbeen used nor advertised, so there could be no prejudice against it; noone had yet allowed me to get so far as quoting price, so it wasnt tooexpensive.

The process of elimination brought me to the absurd conclusion that thefault must lie in me. Not in my appearance, I reasoned, for I was apersonable young man, a little over thirty at the time, with no obviousdefects a few visits to the dentist wouldnt have removed. Of course I dohave an unfortunate skin condition, but such a thing's an act of God, asthe lawyers say, and people must take me as I am.

No, it wasnt my appearance ... or was it? That monstrously outsizedpump! Who wanted to listen to a salestalk from a man apparently preparedfor an immediate gasattack? There is little use in pressing yourtrousers between two boards under the mattress if you discount suchneatness with the accouterment of an invading Martian. I uncoiled thehose from my shoulder and eased the incubus from my back. Leaving themvisible from the corner of my eye, I crossed the most miserable lawn yetencountered.

It was composed of what I since learned is Bermuda, a plant mostSouthern Californians call--with many profane prefixes--devilgrass. Itwas yellow, the dirty, grayish yellow of moldy straw; and bald, scuffedspots immodestly exposed the cracked, parched earth beneath. Over thewalk, interwoven stolons had been felted down into a ragged mat,repellent alike to foot and eye. Perversely, onto what had once beenflowerbeds, the runners crept erect, bristling spines showing faintlygreen on top--the only live color in the miserable expanse. Where thegrass had gone to seed there were patches of muddy purple, patches whichenhanced rather than relieved the diseased color of the whole andemphasized the dying air of the yard. It was a neglected, unvaluedthing; an odious appendage, a mistake never rectified.

"Madam," I began, "your lawn is deplorable." There was no use giving herthe line about I-can-see-you-are-a-lady-who-cares-for-lovely-things.Anyway, now the pump was off my back I felt reckless. I threw the wholebook of salesmanship away. "It's the most neglected lawn in theneighborhood. It is, madam, I'm sorry to say, no less than a disgrace."

She was a woman beyond the age of childbearing, her dress revealing theoutlines of her corset, and she looked at me coldly through rimlessglassing biting the bridge of her inadequate nose. "So what?" she asked.

"Madam," I said, "for ten dollars I can make this the finest lawn in theblock, the pride of your family and the envy of your neighbors."

"I can do better things with ten dollars than spend it on a bunch ofdead grass."

Gratefully I knew I had her then and was glad I hadnt weakly given in toan impulse to carry out the crackpot's original instructions. When theystart to argue, my motto is, theyre sold. I took a good breath and woundup for the clincher.

I won't say she was an easy sale, but afterall I'm a psychologist; Ifound all her weak points and touched them expertly. Even so, she mademe cut my price in half, leaving me only twofifty according to myagreement with Miss Francis, but it was an icebreaker.

I got the pump and hose, collecting at the same time an audience ofbrats who assisted me by shouting, "What ya goin a do, mister?" "What'sat thing for, mister?" "You goin a water Mrs Dinkman's frontyard,mister?" "Do your teeth awwis look so funny, mister? My grampa takes histeeth out at night and puts'm in a glass of water. Do you take out yourteeth at night, mister?" "You goin a put that stuff on our garden too,mister?" "Hay, Shirley--come on over and see the funnylooking man who'sfixing up Dinkman's yard."

They were untiring, shrilling their questions, exclamations andcomments, completely driving from my mind the details of the actualapplication of the Metamorphizer. Anyway, Miss Francis had beenconcerned with putting it in the irrigation water--which didnt apply inthis case. I thought a moment. A gallon was enough for thirty acres;half a pint should suffice for this--more than suffice. Irrigationwater, nonsense--I'd squirt it on and tell the woman to hose it downafterward--that'd be the same as putting it in the water, wouldnt it?

To come to this practical conclusion under the brunt of the children'sassault was a remarkable feat. As I dribbled the stuff over the sorrydevilgrass they kicked the pump--and my shins--mimicking my actions,tripping me as they skipped under my legs, getting wet with theMetamorphizer--I hoped with mutually deleterious effect--and generallymaking me more than ever thankful for my bachelor condition.

Twofifty, I thought, angrily squirting a fine mist at a particularlydreary spot--and it isnt even selling. Manual labor. Working with myhands. I might as well be a gardener. College training. Wide experience.Alert and aggressive. In order to dribble stuff smelling sickeningly ofcarnations on a wasted yard. I coiled up my hose disgustedly andcollected a reluctant five dollars.

"It don't look any different," commented Mrs Dinkman dubiously.

"Madam, Professor Francis' remarkable discovery works miracles, but notin the twinkling of an eye. In a week youll see for yourself, providedof course you wet it down properly."

"In a week youll be far gone with my five dollars," diagnosed MrsDinkman.

While this might be superficially true, it was an unfair and unkindthing to say, and it wounded me. I reached into my pocket and drew outan old card--one printed before I'd had an irreconcilable differencewith the firm employing me at the time.

"I can always be reached at this address, Mrs Dinkman," I said, "shouldyou have any cause for dissatisfaction--which I'm sure is quiteimpossible. Besides, I shall be daily in this district demonstrating thevalue of Dr Francis' Lawn Tonic."

That was certainly true; unless I made a better connection. Degradingmanual labor or not, I intended to sell as many local people as possibleon the strength of having found a weak spot in the wall ofsalesresistance before the effects of the Metamorphizer became apparent.For, in strict confidence, and despite its being an undesirable negativeattitude, I was a little dubious that those effects--or lack ofthem--would stimulate further sales.

_3._ My alarmclock, as it did every morning, Sundays included, rang atsixthirty, for I am a man of habit. I turned it off, rememberinginstantly I had given Miss Francis neither her pump nor her share of thesale. Of course it was more convenient and timesaving to bring them bothtogether and I was sure she didnt expect me to follow instructions tothe letter, like an officeboy, any more in these matters than sh

e had inher restriction to agricultural use.

Still, it was remiss of me. The fact is, I had spent her money as wellas my own--not on dissipation, I hasten to say, but on dinner and aninstallment of my roomrent. This was embarrassing, but I looked upon itmerely as an advance--quite as if I'd had the customarydrawingaccount--to be charged against my next commissions. My acceptanceof the advance merely indicated my faith in the future of theMetamorphizer.

I dissolved a yeastcake in a glass of water; it's very healthy and I'dheard it alleviated dermal irritations. Lathering my face, I glancedover the list culled from the dictionary and stuck in the mirror thenight before, for I have never been too tired to improve my mind. Bythis easy method of increasing my vocabulary I had progressed, at thetime, down to the letter K.

While drinking my coffee--never more than two cups--it was my custom toread and digest stock and bond quotations, for though I had noinvestments--the only time I had been able to take a flurry there was anunforeseen recession in the market--I thought a man who didnt keep upwith trends and conditions unfitted for a place in the businessworld.Besides, I didnt expect to be straitened indefinitely and I believed inbeing ready to take proper advantage of opportunity when it came.

As a man may devote the graver part of his mind to a subject and thenturn for relaxation to a lighter aspect, so I had for years beeninterested in a stock called Consolidated Pemmican and AlliedConcentrates. It wasnt a highpriced issue, nor were its fluctuationsstartling. For six months of the year, year in and year out, it would bequoted at 1/16 of a cent a share; for the other six months it stood at1/8. I didnt know what pemmican was and I didnt particularly care, butif a man could invest at 1/16 he could double his money overnight whenit rose to 1/8. Then he could reverse the process by selling before itwent down and so snowball into fortune. It was a daydream, but aharmless one.

Satisfying myself Consolidated Pemmican was bumbling along at its lowlevel, I reluctantly prepared to resume Miss Francis' pump. It seemedless heavy as I wound the hose over my shoulder and I felt this wasntdue to the negligible quantity I'd expended on Mrs Dinkman's grass. Ijust knew I was going to have a successful day. I had to.

In moments of fancy I often think a salesman is more truly a creativeartist than many of those who arrogate the title to themselves. He useswords, on one hand, and the receptivity of prospects on the other, tomold a cohesive and satisfying whole, a work of Art, signed and dated onthe dotted line. Like any such work, the creation implies thoughtful andcareful preparation. So it was that I got off the bus, polishing a newsalestalk to fit the changed situation. "One of your neighbors ..." "Ihave just applied ..." I sneered my way past those houses refusing myservices the day before; they couldnt have the Metamorphizer at anyprice now. Then it hit my eyes.

Mrs Dinkman's lawn, I mean.

The one so neglected, ailing and yellow only yesterday.

It wasnt sad and sickly now. The most enthusiastic homeowner wouldnthave disdained it. There wasnt a single bare spot visible in the wholelush, healthy expanse. And it was green. Green. Not just here and there,but over every inch of soft, undulating surface; a pale applegreen wherethe blades waved to expose its underparts and a rich, dazzling emeraldon top. Even the runners, sinuously encroaching upon the sidewalk, weredeeply virescent.

The Metamorphizer worked.

The Metamorphizer not only worked, but it worked with unbelievablerapidity. Overnight. I knew nothing about the speed at which ordinaryfertilizers, plant stimulants or hormones took hold, but commonsensetold me nothing like this had ever happened so quickly. I had beenindulging in a little legitimate puffery in saying the inoculant workedmiracles, but if anything that had been an understatement. It just wentto show how impossible it is for a real salesman to be too enthusiastic.

Nerves in knees and fingers quivering, I walked over to join the groupcuriously inspecting the translated lawn. I, _I_ had done this; out ofthe most miserable I'd made the loveliest--and for a paltry fivedollars. I tried to recapture the memory of what it had looked like inorder to relish the contrast more, but it was impossible; the vividpresent blotted out the decayed past completely.

"Overnight," someone said. "Yessir, just overnight. Wouldnt of believedit if I hadnt noticed just yesterday how much worse an the city dump itlooked."

"Bet at stuff's ten inches high."

"Brother, you can say that again. Foot'd be closer."

"Anyhow it's uh fattestlookin grass I seen sence I lef Texas."

"An the greenest. Guess I never did see such a green before."

While they exclaimed about the beauty and vigor of the growth, my mindwas racing in high along practical lines. Achievement isnt worth muchunless you can harness it, and in today's triumph I saw tomorrow'sbenefit. No more canvassing with a pump undignifiedly on my back, nomore manual labor; no, bold as the thought was, not even any more directselling for me. This was big, too big to be approached in any cockroach,build-up-slowly-from-the-bottom way. It was a real top deal, in a classwith nylon or jukeboxes or bubblegum. You could smell the money in it.

First of all I'd have to tie Josephine Francis down with an ironcladcontract. Agents; dealerships; distributors and a general salesmanager,Albert Weener, at the top. Incorporate. Get it all down in black andwhite and signed by Miss Francis right away. For her own good. Anidealistic scientist, a frail woman, protect her from the vultures who'dtry to rob her as soon as they saw what the Metamorphizer would do. Sucha woman wouldnt have any business sense. I'd see she got a comfortableliving out of it and free her from responsibility. Then she could potteraround all she liked.

Incorporate. Interest big money. Put it on a nationwide basis. A cut forthe general salesmanager on every sale. Besides stock. Take the patentin the company's name. In six months I'd be on my way to being amillionaire. I had certainly been right up on my toes in picking theMetamorphizer as a winner in spite of Miss Francis' kitchen and her lackof aggressiveness. Instinct, the unerring instinct of a wideawakesalesman for the right product--and for the right market. I mustntforget that. Had I been content with her original limitation I'd stillbe bumbling around trying to interest Farmer Hicks in some Metamorphizerfor his hay.

"Ja notice how thick it was?"

"Well, that's Bermuda for you. Tell me they actually plant it on purposein Florida."

"No kiddin?"

"Yessir. Know one thing--even if it looks pretty right now, I wouldntwant that stuff on my place. Have to cut it every day."

"Bet ya. Toughlookin too. I rather take my exercise in bed."

That's an angle, I thought--have to get old lady Francis to modify herformula or something. Else we'll never get rich. Slow down the rate ofgrowth, dilute it--ought to be more profitable too.... Have to find outhow cheaply the inoculant can be produced--no more inefficient handmethods.... Of course the fastness of growth wouldnt affect the sale tofarmers--help it in fact. No doubt she'd had more than I originallythought in that aspect, I conceded generously. We could let them applyit themselves ... mailorder advertising ... cut costs that way.... Thinkof clover and alfalfa--or werent they grasses? Anyway, imagine hay orwheat as tall as Iowa corn and corn higher than a smalltown cityhall!Fortune--there'd be a dozen fortunes in it.

I began perspiring. The deal was getting bigger and bigger. It wasntjust a simple matter of cutting in on a good thing. All the angles,which were multiplying at a tremendous rate, had to be covered before Isaw Miss Francis again; I darent miss any bets. I needed a staff ofagricultural experts--anyway someone who could cover the scientificside. Whatever happened to my freshman chemistry? And a mob of lawyers;you'd have to plug every loophole--tight. But here I was without afinancial resource--couldnt hire a ditchdigger, much less the highpricedtalent I needed--and someone else might get a brainstorm when he saw thelawn and beat me to it. I visioned myself cheated of my million....

Yes ... a really fast worker--some unethical promoter willing to stoopto devious methods--might pass at any moment and grasp thepossibilities, have Miss Francis signed up

before I'd even got the dealstraight in my mind. How could he miss, seeing this lawn? Splendid,magnificent, beautiful. No one would ever call this stuffdevilgrass--angelgrass would be more appropriate to the implications ofsuch a heavenly green. Millions in it--simply millions....

"Say--arent you the fellow put this stuff on?"

Halfadozen vacant faces gaped at me, the burdening pump, the caudalhose. Curiosity, interest, imbecile amusement argued in their expressionwith the respect due the worker of the transformation; it was the sortof look connected with salesresistance of the most obstinate kind. Theydistracted me from thinking things through.

"Miz Dinkman's sure looking for you. Says she's going to sue you."

Here was an unfortunate development, an angle to end all angles.Unfavorable publicity, the abortifacient of new enterprises, would meanyou could hardly give the stuff away. My imagination raced throughcolumns of newsprint in which the Metamorphizer was made the butt ofreporters' humor. Mrs Dinkman's ire would have to be placated, boughtoff. Perhaps I'd better discuss developments with Miss Francis rightaway, afterall.

Whatever I decided, it was advisable for me to leave this vicinity. Iwas in no financial position to soothe Mrs Dinkman and it was dubious,in view of her attitude, whether it would be possible to sell any morein the immediate neighborhood. Probably a new territory was the answerto my problem; a few sales would give me both cash in hand and time tothink.

While I hesitated, Mrs Dinkman, belligerency dancing like a sparklingaura about her, came out of her garage with a rusty, rattling lawnmower.I'm no authority on gardentools, but this creaking, rickety machine wasclearly no match for the lusty growth. The audience felt so too, andthere was a stir of sporting interest as they settled down to watch thecontest.

Determination was implicit in the sharply unnatural lines of her corsetand the firm set of her glasses as she charged into the gently swayingrunners. The wheels turned rebelliously, the mower bit, its rusty bladesgrated against the knife, something clanked forcibly and the machinestopped. Mrs. Dinkman pushed, her back arched with effort--the mowerdidnt budge. She pulled it back. It whirred gratefully; the clankingstopped and she tried again. This time it chewed a handful of grass fromthe edge, found it distasteful and quit once more.

"Anybody know how to make this damn thing work?" Mrs Dinkman askedexasperatedly.

"Needs oil" was helpfully volunteered.

She retired into the garage and returned with a lopsided oilcan. "Oilit," she commanded regally. The helpful one reluctantly pressed histhumb against the wry bottom of the can, aiming the twisted spout at oddparts of the mower. "I dunno," he commented.

"I don't either," said Mrs Dinkman. "You--Greener, Weener--whatever yourname is!"

There was no possibility of evasion. "Yes, mam?"

"You made this stuff grow; now you can cut it down."

Uncouth guffaws from the watching idiots.

"Mrs Dinkman, I--"

"Get behind that lawnmower, young man, if you don't want to be involvedin a lawsuit."

I wasnt afraid of such a consequence in itself, having at the momentnothing to attach, but I thought of Miss Francis and future sales andthat impalpable thing known as "goodwill." "Yes, mam," I repeated.

I discarded pump and hose to move reluctantly toward the mower. Under myfeet I felt the springiness of the grass; was it pure fancy--or did ittruly differ in quality from the lawns I'd trod so indifferently the daybefore?

I took the handle. If oiling had improved the machine, its previousefficiency must have been slight. It went shakily over the first inch ofgrass and then, as it had for Mrs Dinkman, it stopped for me.

By now the spectators had increased to a small crowd and their dullhumor had taken the form of cheerfully offering much gratuitous advice."Tie into it, Slim--build up the old muscle." "Back her up and take agood run." "Go home an do some settinup exercises--come back next year.""Got to put the old back behind it, Bud--give her the gas." "Need adecent mower--no use trying to cut stuff like that with an antique.""Yeah--get a good mower--one made since the Civil War." "No one aroundhere got an honestogod lawnmower?"

The last query evidently nettled local pride, for soon a blithe,beamshouldered little man trundled up a shiny, rubbertired machine."Thisll do the business," he announced confidently as I relinquished thespotlight to him with understandable readiness. "It's a regularjimdandy."

It certainly was. The devilgrass came irreverently above the wheels andflowed with graceful inquisitiveness over the blades, but the brisklittle man pushed heartily and the mechanism revolved with a barelyaudible clicking. It did not balk, complain or hesitate. Cleanly severedends of grass whirled into the air and floated down on the neat smoothswath left behind. Everyone smiled relievedly at the jimdandy's triumphand my sigh was loudest and most heartfelt. I edged away asunobtrusively as I could.

_4._ I have no sympathy with weaklings who complain of the cards beingstacked, but it did seem as though fate were dealing unkindly with me.Here was a good proposition, coming just at the time I needed it mostand it was turning bad rapidly. Walking the short distance to MissFrancis' I was unable to settle my mind, to strike a mentalbalancesheet. There was money; there had to be money--lots and lots ofit--in the Metamorphizer, but it was possible there was trouble--lotsand lots of it--also. The thing was, well, dangerous. What was the useof expending ability in selling something which could have kickbacksacting as deterrents to future sales? Of course a man had to takerisks....

The door, after a properly prudent hesitation, clicked brokenly. MissFrancis looked as though she'd added insomnia to her other abstentions,otherwise she had not changed, even to her skirt and the smudge on herleft nostril. "If youve come about the icebox youre a week late. I fixedit myself," she greeted me gruffly.

"Weener," I reminded her, "Albert Weener--remember? I'm selling--thatis, I'm going to sell the product you invented to make plants eatanything."

"Oh. Weener--yes." She produced the toothpick and scratched her chinwith it. "About the Metamorphizer." She paused and rubbed her elbow. "Amistake, I'm afraid. An error."

Aha, I thought, a new deal. Someone's offered to back her. Steal herbrainchild, negate all my efforts to make her independent and cheat meof the reward of my spadework. You wouldnt think of her as a frailcredulous woman, easily taken in by the first smooth talker, but a womanis a woman afterall.

"Look, Miss Francis," I argued, "youve got a big thing here, a greatthing. The possibilities are practically unlimited. Of course youll haveto have a manager to put it across--an executive, a man with businessexperience--someone who can tap the great reservoir of buying power bythe conviction of a new need. Organize a sales campaign; rationalizeproduction. Put the whole thing on a commercial basis. For all this youneed a man who has contacted the public on every level--preferablydoortodoor and with a varied background."

She strode past the stove, which had gathered new accreta during thenight and looked in the cloudy mirror as though searching for amisplaced thought. "No doubt, Weener, no doubt. But before all theseromantically streamlined things eventuate there must be a hiatus. In myhaste I overlooked a detail yesterday, trivial maybe--perhaps vital. Ishould never have let you start out so soon."

This was bad; I was struggling now for my job and for the future of theMetamorphizer. "Miss Francis, I don't know what you mean by mistakes ortrivial details or how I could have started out too soon, but whateverthe trouble is I'm sure it can be smoothed out easily. Sometimes, youknow, obstacles which appear tremendous prove to be nothing at all inexperienced hands. I myself have had occasion to put things right for anumber of different concerns. Really, Miss Francis, you mustnt letopportunity slip through your fingers. Believe me, I know what a bigthing your discovery is--Ive seen what it does."

She turned those too sharp eyes on me discomfortingly. "Ah," she said,"so soon?"

"Well," I began, "it certainly acted quickly ..."

I stopped when I saw she wasnt hearing me. She sat down in the onlyempty chair an

d drummed her fingers against big white teeth. "Even undera microscope," she muttered, "no perceptible reaction for fortyeighthours. Laboratory conditions? Or my own idiocy? But I approximated ..."Her voice trailed off and for a full minute the absolute silence of thekitchen was broken only by the melodramatic dripping of a tap.

She made an effort to pull herself together and addressed me in her oldabrupt way. "Corn or wheat?"

"Ay?"

"You said youve seen what it does. I asked you if you had applied it tocorn or wheat--or what?"

She was looking at me so fixedly I had a slight difficulty in putting mywords in good order. "It was neither, mam. I applied some of the stuffto a lawn--"

"A _lawn_, Weener?"

"Y-yes, mam."

"But I said--"

"General instructions, Miss Francis. I'm sure you didnt mean to tie myhands."

Another long silence.

"No, Weener--I didnt mean to tie your hands."

"Well, as I was saying, I applied some of the stuff to a lawn. Exactlyaccording to your instructions--"

"In the irrigation water?"

"Well, not precisely. But just as good, I assure you."

"Go on."

"A terrible lawn. All shot. Last night. This morning--"

"Stop. What kind of grass? Or don't you know?"

"Of course I know," I answered indignantly. Did she think I was anidiot? "It was devilgrass."

"Ah." She rubbed the back of her hand against her singularly smoothcheek. "Bermuda. _Cynodon dactylon._ Stupid, stupid, stupid. How couldI have been so blind? Did I think only the corn would be affected andnot the weeds in the furrows? Or that something like this might nothappen?"

I didnt feel like wasting any more time listening to her soliloquy."This morning," I continued, "it was as green--"

"All right, Weener, spare me your poetry. Show it to me."

"Well now, Miss Francis ..." I wanted, understandably enough, to discussfuture arrangements before she saw Dinkman's lawn.

"Immediately, Weener."

When dealing with childish persons you have to cater to their whims. Irid myself of the pump--I'd never dreamed I'd be reluctant to part withthe monster--while she made perfunctory and unconvincing motions to fitherself for the street. Of course she neither washed nor madeup, but shepeered in the glass argumentatively, pulled her jacket down decisively,threw her shoulders back to raise it askew again and gave the swirl ofhair a halfhearted pat.

"I'd like to go over the matter of organizing--"

"Not now."

I was naturally reluctant to be seen on the street with so conspicuous afigure, but I could hardly escape. I tried to match her swinging stride,but as she was at least six inches taller I had to give a sort of skipbetween steps, which was less than dignified. Searching my mind to finda tactful approach again to the subject of proper distribution of theMetamorphizer, I felt my opportunity slipping away every moment. She, onher part, was silent and so abstracted that I often had to put out aguiding hand to avert collision with other pedestrians or stationaryobjects.

I doubt if I'd been gone from Mrs Dinkman's threequarters of an hour. Ihad left a small group excited at the free show consequent upon the toosuccessful beautification of a local eyesore; I returned to a sizablecrowd viewing an impressive phenomenon. The homely levity had vanished;no one shouted jovial advice. Opinions and comments passed in whispersaccompanied by furtive glances toward the lawn, as though it weresentient and might be offended by rude speculation. As we pushed throughthe bystanders I was suddenly aware of their cautious avoidance ofcontact with the grass itself. The nearest onlookers stood a respectfulyard back and when unbalanced by the push of those behind went throughsuch antics to avoid treading on it, while at the same time preservingthe convention of innocence of any taboo that they frequently pivotedand pirouetted on one foot in an awkward ballet. The very hiding oftheir inhibition emphasized the new awesomeness of the grass; it was nolonger to be lightly approached or frivolously treated.

Now I am not what is generally called a man of religious sensibilities,having long ago discarded belief in the supernatural; and I am notovercome at odd moments by mystical feelings. Furthermore I had beenintimate with this particular patch of vegetation for some eighteenhours. I had viewed its decaying state; I had injected life into it; Ihad seen it in the first flush of resurrection. In spite of all this, Itoo fell under the spell of the grass and knew something compounded ofwonder and apprehension.

The neatly cut swaths of the little man with the jimdandy mower came toa dramatic end in the middle of the yard. Beyond this shorn portion thegrass rose in a threatening crest, taller than a man's knees; green,aloof and derisive. But it was not this forbidding sight which gave mesuch a queer turn. It was the mown part; for I recalled how the briskman's machine had cut close and left behind short, crisp stems. Now thispiece was almost as high as when I'd first seen it--grown faster in anhour than ordinary grass in a month.

_5._ I stole a look at Miss Francis to see how she was taking the sight,but there was no emotion visible on her face. The toothpick was oncemore in play and the luminous eyes fixed straight ahead. Her legs werespread apart and she seemed firmly in position for hours to come, asthough she would wait for the grass to exhaust its phenomenal growth.

"Why did they quit cutting?" I asked the man standing beside me.

"Mower give out--dulled the blades so they wouldnt cut no more."

"Going to give up and let it grow?"

"Hell, no. Sent for a gardener with a powermower. Big one. Cut anything.Ought to be here now."

He was, too, honking the crowd from the driveway. Mrs Dinkman was withhim, looking at once indignant, persecuted, uncomfortable andselfrighteous. It was evident they had failed to reach any agreement.

The gardener slammed the door of the senescent truck with vehement lackof affection. "I cut lots a devilgrass, lady, but I won't tie into thisovergrown stuff at that price. You got no right to expect it. I knowwhat's fair and it's not reasonable to count on me cutting this like itwas an ordinary lawn. You know yourself it isnt fair."

"I'll give you ten dollars and that's my last word."

"Listen, lady, when I get through this job I'll have to take my mowerapart and have it resharpened. You think I can afford to do that for atendollar job?"

"Ten dollars," repeated Mrs Dinkman firmly.

The gardener appealed to the gallery. "Listen, folks: now I ask you--isthis fair? I'm willing to be reasonable. I understand this lady's introuble and I'm willing to help, but I can't do a twentyfivedollar jobfor ten bucks, can I?"

It was doubtful if the observers were particularly concerned withjustice; what they desired was action, swift and drastic. A generalresentment at being balked of their amusement was manifest in murmurs of"Go ahead, do it." "What's the matter with you?" "Don't be dumb--do itfor nothing--youll get plenty business out of it." They appealed to hisnobler and baser natures, but he remained adamant.

Not to be balked by his churlishness, they passed a hat and collected$8.67, which I thought a remarkably generous admission price. When thiswas added to Mrs Dinkman's ten dollars the gardener, still protesting,reluctantly agreed to perform.

Mrs Dinkman prudently holding the total, he unloaded the powermower withmany flourishes, making quite an undertaking of oiling and adjusting theroller, setting the blades; bending down to assure himself of thegasoline in the small tank, finally wheeling the contraption into placewith great spirit. The motor started with a disgruntled put! changinginto a series of resigned explosions as he guided it over the lawncrosswise to the lines of his predecessor. Miss Francis followed everymotion with rapt attention.

"Did you expect this?" I asked.

"Ay? The abnormally stimulated growth, you mean?"

"Yes."

"Yes and no. Work in the laboratory didnt indicate it. My own fault; Ididnt realize at once making available so much free nitrogen would havesuch instant results. But last night--"

"Yes?"

/> "Not now. Later."

The powermower went nicely, I might almost say smoothly, over the stuffcut before, muttering and chickling happily to itself as it dragged thepanting gardener, inescapably harnessed, in its wake. But the mown areawas narrow and the machine quickly jerked through it and made the lasteasy journey along the wall of untouched devilgrass beyond.

The gardener, without hesitation, aimed his machine at the thicket ofgrass. It growled, slowed, coughed, spat, struggled and thrashed on andfinally conked out.

"Ah," said Miss Francis.

"Oh," said the spectators.

"Sonofabitch," said the gardener.

He yanked the grumbling mower back angrily, inspecting its mechanism inthe manner of a mother with a wayward son and began again. There wasdesperate determination in his shoulders as he added his forward thrustto the protesting rhythm. The machine went at the grass like a bulldogattacking a borzoi: it bit, chewed, held on. It cut a new six inchesreadily, another foot slowly--and then with jolts and misfires and loudimprecations from the gardener, it gave up again.

"You," judged Mrs Dinkman, "don't know how to cut grass."

The gardener wiped his sweaty forehead with the inside of his wrist."You--you should have a law against you," he answered bitterly andinadequately.

But the crowd evidently agreed with Mrs Dinkman's verdict, for therewere mutterings of "It's a farmer's job." "Get somebody with a scythe.""That's right--get a scythe." "Got to have a scythe to cut hay likethat." These remarks, uttered loudly enough for him to hear, sodiscouraged the gardener that after three more futile tries he reloadedhis equipment and left amidst jeers and expressions of disfavor withoutattempting to collect any of the money.

For some reason the failure of the powermower lightened the atmosphere.Everyone, including Mrs Dinkman, seemed convinced that scything was thesolution. Tension relaxed and the bystanders began talking in somethingabove a whisper.

_6._ "This will just about ruin our sales," I said.

Miss Francis suspended the toothpick before her chin and looked at me asthough I'd said dirty words in the presence of ladies.

"Well it will," I argued. "You can't expect people to have their lawnsinoculated if they find out it's going to make grass act this way."

Her eyes might have been microscopes and I something smeared on a slide."Weener, youre the sort of man who peddles _Life Begins at Forty_ to theinmates of an old peoples' home."

I couldnt see what had upset her. The last idea had sound salesappeal,but it was a low income market.... Oh well--her queer notions andobscure reactions undoubtedly went with her scientific gift. You haveto lead individuals of this type for their own good, otherwise theyspend their lives wandering around in a dreamy fog, accomplishingnothing.

"I still believe youve got something," I pointed out. "You yourself saidit wasnt perfected, but perhaps you havent realized how far frommarketable it actually is yet. Now then," I went on reasonably, "yourejust going to have to dilute it or change it or do something to it, sowhile it will make grass nice and green, it won't let it grow wild likethis."

The fixed look could be annoying. It was nearly impossible to turn youreyes away without rudeness once she caught them. "Weener, theMetamorphizer is neither fertilizer nor plant food. It is a chemicalcompound producing a controlled mutation in any treated member of thefamily Gramineae. Dilution might make it not work--the mutation mightnot take place--but it couldnt make it half work. I could change yournature by forcibly injecting an ounce of lead into your cerebellum. Thechange would not only be irrevocable, but it wouldnt make the slightestdifference if the lead were adulterated with ironpyrites or not."

"But, Miss Francis," I expostulated, "you'll have to do _something_."

She threw her hands into the air, a theatrical gesture even more thanordinarily unbecoming. "Why?"

"Why? To make your discovery marketable, of course."

"Now? In the face of this?"

"Miss Francis," I said with dignity, "you are a lady and my selfrespectmakes me treat you with the courtesy due your sex. You advertised for asalesman. Instead of sneering at my honest efforts to put yourmerchandise across to the public, I think youd be better advised toworry about such lowbrow things as keeping faith."

"Am I to keep faith in a vacuum? You came to me as a salesman and I mustgive you something to sell. This is simple morality; but if such a grantentails concomitant evils, surely I am absolved of my originalcontract."

"I don't know what youre talking about," I told her frankly. "Yourstuff made the grass grow too fast, that's all. You should change theformula or find a new one or else ..."

"Or else youll have been left with nothing to sell. I despair of makingthe point about changing the formula; your trust in my powers is tooreverent. Again, I'm not an arrogant woman and I'll admit to someresponsibility. Make the world fit for Alfred Weener to make a livingin."

"It's Albert, not Alfred," I corrected her. I'm not touchy, goodnessknows, but afterall a name's a piece of property.

"Your pardon, Albert." She looked down at me with such a placatory andgenuinely feminine smile I decided I'd been foolish to be offended.She's a nut of course, I thought indulgently, someone whose life isbounded by theories and testtubes, a woman with no conception ofpractical reality. Instead of being affronted it would be better to showher patiently how essential my help was to her.

"Of all people," she went on, searching my face with those discomfitingeyes, "of all people Ive the least cause for moral snobbery. Anxious toget a few dollars to carry on my work--and what was such anxiety butselfindulgence?--I threw the Metamorphizer to you and the world before Irealized that it was not only imperfect, but faulty. Hell is paved withgood intentions and the first result of my desire to benefit mankind hasbeen to injure the Dinkmans. Meditation in place of infatuation wouldhave shown me both the immediate and ultimate wrongs. I doubt if youdbeen gone an hour yesterday when I knew I'd made a blunder in permittingyou to go out with danger in both hands."

"I don't know what youre getting at," I said stiffly, for it sounded asthough she were regarding me as a child.

"Why, as I was sitting, composing my thoughts toward extending theeffectiveness of the Metamorphizer beyond gramina, it suddenly becameclear to me I'd erred about not knowing how long the effect of theinoculations would last."

"You mean you found out?" If she brought the thing under control and theeffect lasted a specified time there might be repeat business afterall.

"I found out a great deal by using speculation and logic for a changeinstead of my hands and memory. I sat and thought, and though this is anunorthodox way for a scientist to proceed, I profited by it. I reasoned:if you change the genetic structure of a plant you change itpermanently; not for a day or an hour, but for its existence. I'm notspeaking of chance mutations, you understand, Weener, coming about overa course of generations, generations which include sports, degenerates,atavars andsoforth; but of controlled changes, brought about throughhuman intervention. Inoculation by the Metamorphizer might be comparedto cutting off a man's leg or transplanting part of his brain.Albert--what happens when you cut off a man's leg?"

I was tired of being talked to like a grammarschool class. Still, Ihumored her. "Why, then he has only one leg," I answered agreeably ifidiotically.

"True. More than that, he has a onelegged disposition. His whole ego,his entire spirit is changed. No longer a twolegged creature, reduced,he is another--warped, if you like--being. To come to the immediatepoint of the grass: if you engender an omnivorous capacity you implantan insatiable appetite."

"I don't catch."

"If you give a man a big belly you make him a hog."

A chevvy coupe, gently breathing steam from its radiator cap,interrupted. From its turtle hung the blade of a scythe and on thenervously hinged door had been hopefully lettered _Arcangelo Barelli,Plowing & Grading_.

While the coupe was trembling for some seconds before quieting down, Isighed a double relief, at Miss Francis' forgetf

ulness of the money dueher and the soothing of my fears for the lawn's eating its way downwardto China or India. The remark about gluttonous abdomens was disturbing.

"And of course there will be no further sale of the Metamorphizer," sheconcluded, her eyes now totally concerned with the farmer who wasopening the turtle with the air of a man expecting to be unpleasantlyastonished.

Mr Barelli came as to a deathbed, a consoling but hopeless smilewidening his narrow face only inconsiderably. At the scythe cradled inhis arms someone shouted, "Here's old Father Time himself." Mr Barelliwasnt amused. Brushing his forehead thoughtfully with tender fingers hesurveyed with saddened eye the three graduated steps of grass. The laststep, unessayed by his predecessors, rose nearly four feet, as alien tothe concept of lawn as a field of wheat.

"Think you can cut it?" one of the audience asked.

Mr Barelli smiled cheerlessly and didnt answer. Instead, he uprootedfrom his hip pocket a slender stone and began phlegmatically to caressthe blade of the scythe with it.

"Hay, that stuff's not goin to stop growin while you fool around."

"Got to do things right," explained Mr Barelli gently.

The rhythmic friction of stone against steel prolonged suspenseunbearably. All kinds of speculation crowded my mind while the leisurelyperformance went on. The grass was growing rapidly; faster thanvegetation had ever grown before. Could it grow so quickly the farmer'sscythe couldnt keep up with it? Suppose it had been wheat or corn?Planted today, it would be ready to harvest next week, fully ripe. Theoriginal dream of Miss Francis would pale compared with the reality.There was still--somewhere, somehow--a fortune in the Metamorphizer....

Ready at last, Mr Barelli walked delicately across the stubble as if itwere a substance too precious to be trampled brutally. Again he measuredthe rippling, ascending mass with his eye. It was the look of abridegroom.

"What you waitin for?"

Unheeding, he scraped bootwelt semicircularly on the sward as though tomark a stance. Once more he appraised the grass, crooked his knee,rested his hands lightly on the two short, upraised handholds. Satisfiedat length with his preparations, he finally drew the scythe back with asweeping motion of both arms and curved it forward close to the ground.It embraced a sudden island lovingly and a sheaf of grass swooned into aheap. I was reminded of old woodcuts in a history of the FrenchRevolution.

The bystanders sighed in harmony. "Nothing to it ... should a had him inthe first place ... can't beat the old elbowgrease. No, sir,musclepower'll do it every time ... guess it's licked now all right, allright...." Mr Barelli duplicated his sweep and another sheaf fell.Another. And another....

"One of the oldest human rituals," remarked Miss Francis, swaying herbody in time with the farmer's. "An act of devotion to Ceres. But allthis husbandman reaps is _Cynodon dactylon_. A commentary."

"Progress," I pointed out. "Now they have machines to harvest grain. Alluptodate farmers use them; only the backward ones stick to primitivetools and have to make a living by taking on odd jobs."

"Progress," she repeated, looking from the scythewielder to me and backagain. "Progress, Weener. A remarkable conception of the nineteenthcentury...."

The less intense spectators began to move off; not, to be sure, withoutbackward glances, but the metronomic swing of Mr Barelli's bladeindicated it was all over with the rank grass now. I too should havebeen on my way, writing off the Metamorphizer as a total loss andconsidering methods for making a new and more profitable connection. Notthat I was one to leave a sinking ship, nor had I lost faith in thepotentialities of Miss Francis' discovery; but she either wasnt smartenough to modify her formula, or else ... but there really wasnt any "orelse". She just wasnt smart enough to make the Metamorphizer marketableand she was cheating me of the handsome return which should berightfully mine.

She'd made the stuff and deceived me by an unscrupulously wordedadvertisement, now, no longer interested, she asked airily if furthereffort were essential. Who wouldnt be indignant? And to cap it all shesuddenly ejaculated, "Can't dawdle around here all day" and aftersnatching up a handful of the scythings, she left, rolling her largebody from side to side, galloping her untidy hair up and down over herneck as she took rapid strides. Evidently the attractions of her messykitchen were more to her taste than the wholesome air of outdoors.Pottering around, producing another mare's nest and eventually, Isuppose, getting another victim....

_7._ But I couldnt leave so cavalierly. Every leaf, stem, and blade ofthe cancerous grass held me in somewhat the same way Miss Francis'intense eyes did. It wasnt an aesthetic or morbid attraction--its basiswas strictly practical. If it could have been controlled--if only thegrowth could be induced on a modified and proper scale--what a product!A fury of frustration rocked my customary calm....

The stretch and retraction of the mower's arms, the swift, brightcurving as the scythe cut deeper, fascinated me. An unscrupulousman--just as a whimsical thought--might go about in the nightinoculating lawns surreptitiously and appear with a crew next day tooffer his services in cutting them. Just goes to show how easy it is tomake dishonest speculations ... but of course such things don't pay inthe long run....

The lush area was being reduced, but perhaps not with the same rapidityas at first when Mr Barelli was at the top of enthusiastic--if theadjective was applicable--vigor. Oftener and oftener and oftener hepaused to sharpen his implement and I thought the cropped shocks werebecoming smaller and smaller. As the movement of the scythe swept theguillotined grass backward, the trailing stolons entangled themselveswith the uncut stand, pulling the sheaves out of place and making thestacks ragged and inadequate looking.

Behind me a cocky voice asked, "What's cooking around here, chum?"

I turned round to a young man, thin as a bamboo pole, elegantlytailored, who yawned to advertise gold inlays. I explained while helooked skeptical, bored and knowing simultaneously. "Who would thaflummox, bah goom?" he inquired.

"Ay?"

He took a pack of playingcards from his pocket and riffled themexpertly. "Who you kidding, bud?" he translated.

"No one. Ask anybody here if this wasnt a dead lawn yesterday and if ithasnt grown this high since morning."

He yawned again and proffered me the deck. "Pick any card," hesuggested. To avoid rudeness I selected one. He put the pack back andsaid, "You have the nine of diamonds. Clever, eh?"

I didnt know whether it was or not. He accepted the pasteboard from meand said, peering out from under furry black eyebrows, "If I brought ina story like that, the chief would fire me before you could say JamesGordon Bennett."

"Youre a reporter?"

"Acute chap. Newspaperman. Name of Gootes. Jacson Gootes, _DailyIntelligencer_, not _Thrilling Wonder Stories_."

I thought I saw an answer to my most pressing problem. One has to stoopoccasionally to methods which, if they didnt lead to important ends,might almost be termed petty; but afterall there was no reason Mr JacsonGootes shouldnt buy me a dinner in return for information valuable tohim. "Let's get away from here," I suggested.

He fished out a coin, showed it to me, waved his arm in the air andopened an empty palm for my inspection. "Ah sho would like to, cunnel,but Ahve got to covah thisyeah sto'y--even if it's out of this mizzblewo'ld."

"I'm sure I can give you details to bring it down to earth," I told him."Make it a story your editor will be glad to have."

"'Glad'!" He pressed tobacco into a slender pipe as emaciated ashimself. "You don't know W R. If he got a beat on the story of Creationhe'd be sore as hell because God wanted a byline."

He evidently enjoyed his own quip for he repeated several times indifferent accents "... God wanted a byline." He puffed a matchflame andsurveyed the field of Mr Barelli's effort. "Hardworkin feller, what?Guess I better have a chat with the bounder--probably closest to thedashed thing."

"Mr Gootes," I said impressively, "I am the man who applied theinoculator to this grass. Now shall we get out of here so you can listento my story?"

"Sonabeesh--thees gona be good. Lead away, amigo--I prepare both ears toleesten."

I drew him toward Hollywood Boulevard and into a restaurant I calculatedmight not be too expensive for his generosity. Besides, he probably hadan expenseaccount. We put a porcelaintopped table between us and hecommanded, "Give down." Obediently I went over all the happenings ofyesterday, omitting only Miss Francis' name and the revealing wording ofthe ad.

Gootes surveyed me interestedly. "You certainly started something here,Acne and/or Psoriasis."

Humor like his was beneath offense. "My name's Albert Weener."

"Mine's Mustard." He produced a plastic cup and rapidly extracted fromit a series of others in diminishing sizes. "I wouldnt have thought itto look at you. The dirty deed, I mean--not the exzemical hotdog. O K,Mister Weener--who's this scientific magnate? Whyre you holding him outon me?"

"Scientists don't like to be disturbed in their researches," Itemporized.

"No more does a man in a whorehouse," he retorted vulgarly. "Story's nogood without him."

That was what I thought and I'm afraid my satisfaction appeared on myface.

"Now leely man--no try a hold up da press. Whatsa matter, you aready hadda beer and da roasta bif sanawich?"

"Maybe you better repeat the order. You know in these cheap places theydon't like to have you sit around and talk without spending money."

"Money! Eh, laddie--I'm nae a millionaire." He balanced a full glass ofwater thoughtfully upon a knifeblade, looking around for applause. Whenit was not forthcoming he meekly followed my suggestion.

"Listen, Gootes," I swallowed a mouthful of sandwich and sipped a littlebeer. "I want to help you get your story."

He waved his hand and pulled a handkerchief out of his ear.

"The point is," I commenced, sopping a piece of bread in the thickgravy, "if I were to betray the confidence involved I couldnt hope tocontinue my connection and I'd lose my chances to benefit from thisremarkable discovery."

"Balls," exclaimed Gootes. "Forget the spiel. I'm not a prospect foryour lawn tonic."

I disregarded the interruption. "I'm not a mercenary man and I believein enlightening the public to the fullest extent compatible withdecency. I'm willing to make a sacrifice for the general good, yet I--"

"--'must live.' I know, I know. How much?"

"It seems to me fifty dollars would be little enough--"

"Fifty potatoes!" He went through an elaborate pantomime of shock,horror, indignation, grotesque dismay and a dozen other assortedemotions. "Little man, youre fruitcake sure. W R wouldnt part with halfa C for a tipoff on the Secondcoming. No, brother--you rang the wrongbell. Five I might get you--but no more."

I replied firmly I was not in need of charity--ignoring his pointed lookat the remains on my plate--and this was strictly a businessproposition, payment for value received. After some bargaining hefinally agreed to phone his managingeditor and propose I'd "come clean"for twenty dollars. While he was on this errand I added pie and coffeeto the check. It is well to be provident and I'd paid for my meal inmore than money.

Jacson Gootes came limply from the phonebooth, his bumptiousness gone."No soap." He shook his head dejectedly. "Old Man said only pity for thelower mammals prevented him from letting me go to work for Hearst rightaway. Sorry."

His nerves appeared quite shattered; capable of restoration only by OldGrandad. After tossing down a couple of bourbons he seemed a littlerecovered, but hardly quite well enough to use an accent or perform atrick.

"I'm sorry also," I said. "Since we can be of no further use to eachother--"

"Don't take a powder, chum," he urged plaintively. "What about a lastgander at the weed together?"

As we walked back I reflected that at any rate I was saved fromsubmitting Miss Francis to vulgar publicity. Everything is for thebest--Ive seen a hundred instances to prove it. Perhaps--whoknew--something might yet happen to make it possible for me to profit bythe freak growth.

"Needs a transfusion," remarked Gootes as we stood on the sidewalkbefore it.

Indeed it was anemically green; uneven, hacked and ragged; shorn of itsemerald beauty. A high fog filtered the late afternoon light to show MrBarelli's task accomplished and the curious watchers gone. It was nosmoothly clipped carpet, yet it was no longer a freakish, exotic thing.Rather forlorn it looked, and crippled.

"Paleface pay out much wampum to get um cut every day."

"Oh, it probably won't take long till the strength is exhausted."

"Says you. Well, Ive got half a story. Cheerio."

I sighed. If only Miss Francis could control it. A fortune ...

I walked home, trying to figure out what I was going to do tomorrow.

_8._ I thought I was prepared for anything after the shocks of the daybefore; I know I was prepared for nothing at all--to find the grass asI'd left it or even reverted to its original decay. Indeed, I was nottoo sure that my memory was completely accurate; that the thing hadhappened so fantastically.

But the devilgrass had outdone itself and made my anticipations foolish.It waved a green crest higher than the crowd--a crowd three times thesize of yesterday's and increasing rapidly. All the scars inflicted onit, the indignities of scythe and mower, were covered by a new and evenmore prodigious stand which made all its former growth appear puny. Boldand insolent, it had repaired the hackedout areas and risen to such aheight that, except for a narrow strip at the top, all the windows ofthe Dinkman house were smothered. Of the garage, only the roof, islandedand bewildered, was visible, apparently resting on a solid foundationof devilgrass. It sprawled kittenishly, its deceptive softness faintlysuggesting fur; at once playful and destructive. My optimism of thenight before was dashed; this voracious growth wasnt going to dwindleaway of itself. It would have to be killed, rooted out.

Now the Dinkman lawn wasnt continuous with its neighbors, but, untilnow, had been set off by chesthigh hedges. The day before these hadcontained and defined the growth, but, overwhelming them in the night,the grass had swept across and invaded the neat, civilized plots behind,blurring sharply cut edges, curiously investigating flowerbeds,barbarously strangling shapely bushes.

But these werent the ravages which upset me; it was reasonable if notentirely comfortable to see shrubbery, plants and blossoms swallowed up.Work of men's hands they may be, but they bear the imprimatur of nature.The cement sidewalk, however, was pure artifice, stamped with thetrademark of man. Indignity and defeat were symbolized by itsoverrunning; it was an arrogant defiance, an outrageous challengeoffered to every man happening by. But the grass was not satisfied withthis irreverence: it was already making demands on curbing and gutter.

"Junior, youve got a story now. W R fired three copyboys and aproofreader he was so mad at himself. Here." Jacson Gootes made a passin the air, simulated astonishment at the twentydollar bill whichappeared miraculously between his fingers and put it in my hand.

"Thank you," I replied coolly. "Just what is this for?"

"Faith, me boy, such innocence Ive never seen since I left the old sod.Tis but a little token of esteem from himself, to repay you for thetrouble of leading me to your scientist, your Frankenstein, yourBurbank. Lead on, my boy. And make it snappy, brother," he added,"because Ive got to be back here for the rescue."

"Rescue?"

"Yeah. People in the house." He consulted a scrap of paper. "Pinkman--"

"Dinkman."

"Dinkman. Yeah--thanks--no idea how sensitive people are when you gettheir names wrong. Dinkmans phoned the firedepartment. Can't get out.Rescue any minute--got to cover that--imperative--TRAPPED IN HOME BYFREAK LAWN--and nail down your scientist at the same time."

I was very anxious myself to see what would happen here so I suggested,since I could take him to the discoverer of the Metamorphizer any time,that we'd better stay and get the Dinkman story first. Withoverenthusiastic praise of my acuteness, he agreed and began practicinghis sleightofhand tricks to the great pleasure of some children, thesame ones, I suspect, who had

plagued me when I was spraying the lawn.

His performance was terminated by the rapidly approaching firesiren. Thecrowd seemed of several minds about the purpose of the red trucksquealing around the corner to a stop. Some, like Gootes, had heard theDinkmans were indeed trapped in the house; others declared the firemenhad come to cut away the grass onceandforall; still others held the loudopinion that the swift growth had generated a spontaneous combustion.

But having made their abrupt face-in-the-ground halt, the truck (orrather the firemen on it) anticlimactically did nothing at all. Helmetedand accoutered, ready for instant action, they relaxed contentedlyagainst the engine, oblivious of grass, bystanders, or presumableemergency. Gootes strolled over to inquire the cause of their indolence."Waiting for the chief," he was informed. Thereupon he borrowed a helmet(possibly on the strength of his presscard) and proceeded to pull fromit such a variety of objects that he received the final accolade fromseveral of his audience when they told him admiringly he ought to be onthe stage.

The bystanders were not seduced by this entertainment into approval ofthe firemen's idleness and inquired sarcastically why they had lefttheir cots behind or if they thought they were still on WPA? The menremained impervious until the chief jumped out of his red roadster andsurveyed the scene napoleonically. "Thought somebody was pulling a rib,"he explained to no one in particular. "All right, boys, there's folks inthat house--let's get them out."

Carrying a ladder the men plunged toward the house. Their boots trod thesprawling runners heavily, spurning and crushing them carelessly. Thegrass responded by flowing back like water, sloshing over ankles andlapping at calves, thoroughly entangling and impeding progress. Pantingand struggling the firemen penetrated only a short way into the massbefore they were slowed almost to a standstill. From the sidelines itseemed as though they were wrestling with an invisible octopus. Feetwere lifted high, but never free of the twining vegetation; the ladderwas pulled angrily forward, but the clutch of the grass upon it becamefirmer with every tug.

At length they were halted, although their efforts still gave anappearance of advance. Thrashing and wrenching they urged themselves andthe now burdensome ladder against the invincible wall. The only resultwas to give the illusion they were burying themselves in the clutchingtentacles. Exertions dwindled; the struggle grew less intense; then theyretreated, fighting their way out of the enveloping mass in a panic ofdesperation, abandoning the ladder.

The chief surveyed them with less than approbation. "Cut your way in,"he ordered. "You guys think those axes are only to bust up furniturewith?"

Obediently, wedges of bright steel flashed against the green wall.

"Impatiently I await the rescue of fair Dinkmans from this enchantedkeep," murmured Gootes, vainly trying to balance his pipe on the back ofhis hand.

It looked as though he would have to contain his impatience for sometime. The firemen slashed unenthusiastically at the grass, which gaveway only grudgingly and by inches. Halfanhour later they triumphantlydragged out the abandoned ladder. "Stuff's like rubber--bounds backinstead of cutting."

"Yeah. And in the meantime those people been telephoning again. Want toknow what the delay is. Want to know what they pay taxes for. Threatento sue the city."

"Let'm sue. Long as theyre in there they can't collect."

"Funny as a flat tire. Get going, goldbrick."