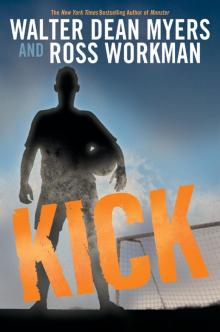

Kick

Walter Dean Myers

KICK

WALTER DEAN MYERS

AND ROSS WORKMAN

To Walter Dean Myers,

an extraordinary and inspiring mentor

—RW

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

—William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), “The Second Coming”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Epigraph

Chapter 01

Chapter 02

Chapter 03

Chapter 04

Chapter 05

Chapter 06

Chapter 07

Chapter 08

Chapter 09

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Also by Walter Dean Myers

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 01

Bill Kelly and I had been friends since we played high school basketball together. I had played strong forward and he had been the quick guard with the sweet outside shot. He had always been bright and the kind of kid who did his homework on time and worried about his grades, and I was always more relaxed. After high school I went into the army and then onto the police force, and Bill went on to law school. I knew he would do well and he did, but he really came into his own when he became a judge. He always seemed to look to do a bit more than he had to, for the community as well as for the people who came through his courtroom. So when he called me and asked me if I would mind coming down to his office to talk about a case he had an interest in, I was flattered.

It was only a twenty-minute drive from my place to the Highland Municipal Courthouse. I parked in the rear of the old Art Deco structure, went through the double doors and past the cafeteria, and made my way to the elevator bank in the east end of the building.

Judge Kelly’s office was on the third floor, and I arrived at two minutes to the hour.

Miss Weinberg, Kelly’s secretary, smiled as she picked up the phone.

“Sergeant Brown is here, sir,” she said.

A moment later the frosted door opened and Judge Kelly, nearly as lean as he had been in his playing days, stepped out.

“Come on in, Jerry,” he said, extending his hand. “How you doing these days?”

“I’m good,” I said. “Fighting the battle of the bulge. Looks like even the salads are fattening these days.”

“You need to come jogging with me,” he said, going behind his desk.

I noticed that there was a young officer already seated in one of the chairs facing the judge.

“Sergeant Jerry Brown, this is Scott Evans. He made the arrest of the young man I’m interested in,” Judge Kelly said.

“Hey, how’s it going?” The young officer stood and extended his hand.

“It’s going well,” I answered.

“Sergeant Brown’s been interested in keeping young people out of trouble for a long time, and as I mentioned to you before, we’ve talked about cases in which we might be able to intervene and keep a kid on the right path,” Judge Kelly said. “This young man’s father was a policeman.”

“Was?” I asked.

“You remember Johnson? Young officer who got caught up in a shoot-out a few years ago?” Kelly leaned back in his chair and clasped his hands behind his neck.

“Yeah. He was a good young . . . his kid is in trouble?” I looked at the arresting officer.

“Scott, why don’t you fill Jerry in?” Judge Kelly asked the officer.

Evans took out his pad, took a few seconds to read his notes, then looked up at me.

“I was on patrol last night, just after nine, when I saw a Ford Taurus driving erratically along the street parallel to the highway. The lights weren’t on and the car was weaving. I thought it was a drunk and I put my lights on. When I did that, the car sped up a bit, then braked, then sped up and skidded into a light pole. No major damages, but I got the feeling whoever was driving was just lucky at that time. I told them over the loudspeaker to turn the engine off, and they complied. Then I ordered them out of the car.

“At first I thought it was an old skinny guy and then I saw that it was a kid. I checked the car and there was a passenger, and she looked even younger than the driver. Okay, so I figured a couple of kids making out in a moving car. I asked the kid for his driver’s license and he doesn’t have one. I asked him how old he was, and he looks at me and says he’s thirteen. I put my light on his face and I see he’s really young. His name is Kevin Johnson.”

“His parents’ car?” I asked.

“No, it’s the girl’s father’s car,” Evans said. “She’s thirteen, and I look at her face and I see she’s been crying. Her face is all puffy and red. I take the guy to the back of the car and ask him what’s going on. He gives me a ‘Nothing.’ So I cuff him and tell him to sit on the sidewalk next to the car, and I go to the girl and I ask her what’s going on. She gives me the same ‘Nothing.’ Which, incidentally, pisses me off. I don’t know the kid is the son of a policeman who was killed in the line of duty.”

“You couldn’t know that,” Judge Kelly said.

“So I get the girl’s ID and her telephone number and I call her house. I get the father and tell him I just stopped two kids in his car and ask him if he knows anything about it.”

“What did he say?” I asked.

“At first he doesn’t say anything, and then, after he’s been thinking for a minute, he says the kid driving must have stolen it and made the girl go along. Okay, so it’s a stolen car rap, kidnapping, driving without a license, damaging city property—the light pole—plus traffic violations. McNamara, that’s the girl’s father, says he doesn’t have another car and he’s going to have to walk to where we were. I tell him to stay home and I’ll bring the girl to his house.”

“Which is where?” I asked.

“Elystan Place,” Evans said. “Over past the water tower.”

“Okay.”

“So I take the girl home and I ask the father if he wants to press charges, because the charges can be pretty steep,” Evans continued. “Meanwhile I’m checking out the girl and she’s looking down and the father’s looking away from her, and the boy, Kevin, is just sitting in my car with his head down.”

“Something’s going on,” I said.

“Yeah, but nobody’s talking, so I asked the father again does he want to press charges, and he says yes,” Scott says. “Then I asked the girl if the boy did anything to her. If he hit her or touched her in any way, and she says no.

“The father tells me that his wife is sick and is it okay if he comes down to the station to press charges in the morning, and I said it was and told him where to come. That’s it.”

“You asked the girl if the boy hit her or touched her,” I said. “What did the father say? Did he look upset?”

Scott hesitated, then shook his head. “No, he just took the girl into the house.”

“According to the precinct desk sergeant, the father came in this morning and asked a lot of questions about what would happen if he pressed charges and what would happen if he didn’t,” Judge Kelly said. “He wanted to know if the girl would have to testify.”

“What was your take on the situation?” I asked Officer Evans. “Did you think this boy—what’s his name?”

“You get the impression Kevin was forcing the girl into anything?”

“I wasn’t sure,” Evans said, leaning forward in his chair. “But as she turned to walk into the house, she looked back at him and smiled. I didn’t know if it meant anything, but she smiled like she was saying everything was okay between them.”

“And how did he look?”

“His eyes were working,” Evans said. “He was looking around and thinking hard, but he kept his mouth shut. I asked him on the way to the station if he thought he was a tough guy.”

“What did he say?”

“Nothing. Not a word.”

“So what do you want me to do?” I asked Judge Kelly.

“Jerry, when we were talking about the program at the club, I knew we were thinking about young African-American kids,” Judge Kelly said, pushing a file folder across the desk. “This kid isn’t African American, but he is a police officer’s son, and maybe a good young man. He’s got no record. No trouble at school. I think McNamara, the girl’s father, might not press charges. I don’t know. This whole case is up in the air right now and can land in a lot of places. If you have the time to look into it . . . ”

“I’ll see what I can do,” I said, standing.

I thanked Evans and took the file.

On the way home I thought again about the meeting at the club and talk about mentoring teenagers. A priest who was there, somewhat less enthusiastic than the rest of us, had talked about how complex some of the situations could get.

I stopped at Holes!, the donut shop on Evergreen, and bought a dozen donuts—six glazed and six unglazed—and a medium coffee. The parking area was almost empty, and I thumbed through the file as I drank the coffee. There was no picture of young Mr. Johnson and I wondered what he looked like. I imagined a surly kid with a slightly turned-up lip and a squint.

I hadn’t known his father personally, but I remembered the funeral of the young Irish-American officer and knew I must have seen the family. Every police funeral is a tragedy as far as I am concerned, and I never wanted to dwell on them.

The girl, Christy, and her family lived in the Brunswick section of town, a neighborhood that had changed a lot since I was a kid. It had been an industrial area, had declined for a while, but now was recovering as the old buildings were being converted into condos to attract an upscale crowd. I recalled there had been an investigation of possible exploitation of immigrant workers in the area.

I drove home, transferred half the donuts to another plastic bag, and put them in the glove compartment. Carolyn would never understand the pressures that demanded a full dozen. Inside the house, I called Gracie at the precinct and asked her to run a search on Michael McNamara, the girl’s father.

“Drunk and disorderly, two years ago. He slapped his wife around a bit but she refused to get an order of protection. And a citation four years ago for illegal parking. You in the office baseball pool this week?”

“I never win the darn thing.”

“Stop whining, Jerry—you in it or not?”

“I’m in it,” I said.

Carolyn saw the bag of donuts on the coffee table and gave me the Look. “Have you forgotten everything the doctor told you?” she asked.

I put on my best wounded face and handed over the sinful six.

Chapter 02

I kept my head down as I watched shoes pass me by. Shiny black high heels clicking against the floor. Beat-up white Nikes spotted with dirt stains. I sat shivering in the waiting room of the Bedford County Juvenile Detention Center. They had turned the air conditioner up extra high. I bet it was to make us feel even worse than we did just being in this place. My head was spinning and I felt sick to my stomach. I couldn’t believe I was locked up. I kept asking myself why I was in this place. I was no criminal.

But I knew I couldn’t tell the truth.

My wrists burned from the handcuffs that the police had put on me when I was arrested. My shoulders ached. The cot they had assigned me felt like concrete. Not that I could sleep anyway. The whole night was playing over and over in my head, like a bad movie I couldn’t forget. I just wanted this mess to be over and to go home.

But I didn’t know how I would face Mom. The worst part about everything last night was seeing Mom when she came to the precinct. It wasn’t like she was mad, just horribly disappointed and sad.

In the middle of the night I woke up to find the door being swung open. An officer was uncuffing another inmate. The kid was older than me.

“Happy to be back home, Morales?” the officer said.

“I know you missed me,” the kid shot back.

“Yeah, but I figured I’d see you again.”

I tried not to look at the kid as he got settled in.

The tattoos on his shoulders ran down his arms. I wondered if he was in a gang, but I definitely wasn’t going to ask him. I pretended to be asleep.

In the morning they brought us out to breakfast, and there were two fights before we reached the food counter. Some of the guys looked too old to be in a juvenile detention center. I wondered if some of them were in gangs, because they were flashing signs at each other. I liked to watch a show on TV called Gangland, where real gang members came and talked about the history of their gangs and what they did as members. But this wasn’t TV. This was my life. I wished it wasn’t.

The food was greasy. I wouldn’t have eaten it even if my stomach felt okay.

After breakfast the guards walked us back to our cells. The uniforms we had to wear were a dull gray, which matched our moods.

The guy in my cell, Morales, asked if I had been arraigned yet. I shook my head no. I didn’t know what he was talking about, but I didn’t want to ask him.

“That’s when you find out what’s gonna happen to you,” he said. “Don’t be acting too tough, man. Maybe you can cop a break.”

The guy looked hard, and every other word that came out of his mouth was a curse.

He told me what was wrong with the place and who to avoid. I was surprised he was friendly. But he also seemed mad at the world, like it had given up on him.

The whole time he was talking, I could feel my heart beating against the inside of my chest. It didn’t feel like a tough heartbeat, either.

All morning I sat around trying to think through what was happening, but I was too scared to concentrate. When the guard came and called my name, I hardly recognized it. He said I had a visitor in the interview room. I hoped it was Mom. I hoped it was her even though I felt terrible about her seeing me in jail.

The interview room was painted a pale white. I glanced up at the clock every now and then; it was behind a metal grille, like it was locked up, too. I imagined all the things a clock would have done to be in here. I guess he’d have to do his time, I thought. I laughed for the first time since the arrest.

I sat alone on the hard plastic chair for nearly fifteen minutes before the door opened. I watched a pair of big brown shoes stop just inside the door and then step toward me. I slowly lifted my head. A tall black man with broad shoulders, wearing a shirt and tie, looked down at me with surprise on his face.

“Kevin Johnson?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, standing. I wondered what he wanted with me.

“I’m Sergeant Jerry Brown,” he said, putting out his hand. I shook it. “Hear you got yourself into some trouble, huh?”

I nodded.

“You want to tell me about it?”

“Not really.” He couldn’t expect me to tell him anything. I didn’t even know him.

He sat down in the chair next to me. I hoped he was as uncomfortable as I was in the hard plastic seat.

“Kevin, let me tell you something about myself. I’m a police officer just like the one who arrested you. Just like your father was. Judge Kelly asked me to look into your case because he had a lot of respect for your father. I did, too,” he said. “I’d like to try to help you if I can. You know the charges,

don’t you?”

“Driving without a license,” I said.

“Driving without a . . . ?” He looked away and then back at me. “Try kidnapping, grand theft auto, destruction of property, and giving false answers. We’re talking felonies, not misdemeanors.”

Kidnapping? I didn’t know they charged me for kidnapping! They got it all wrong.

I tried to stay calm. “A felony? What’s that?”

“It’s a really serious type of crime, Kevin.”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“Weren’t you driving a car that crashed last night? You could do yourself a favor and tell me now, or if you want, you can do it in front of twelve other people who couldn’t care less about you.”

“So, why do you care what happens to me?”

Sergeant Brown raised his eyebrows. “Judge Kelly said you needed some straightening out. He asked me if I wanted to help you and I said I’d give it a try. But you need to be honest with me. With some straight answers and a little luck, you might, just might, not have to stay in here. You are interested in getting out?”

Sergeant Brown spoke in a voice that meant business. He looked at me, waiting for my answer.

“All I want to do is go home,” I said.

“It’s not that simple, young man,” Sergeant Brown said. “You’re going to have to go to the judge’s chambers and explain a lot of things to him. And tell them in a way to make him think you deserve to leave here tonight.”

“I’m not that good at explaining things,” I said. “The cop who handcuffed me didn’t believe me.”

Sergeant Brown kind of puffed up, shook his head a little, and exhaled. “Just what are you good at?” he asked.

“I don’t know. Soccer, I guess,” I answered. “But that’s not going to help me in here, is it? The tournament lottery is tomorrow.”