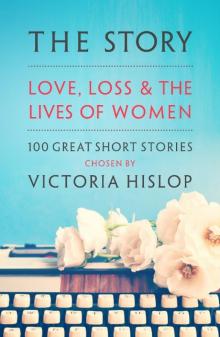

The Story

Victoria Hislop

Start Reading

About this Book

About Victoria Hislop

Also by Victoria Hislop

Table of Contents

www.headofzeus.com

Contents

Cover

Welcome Page

Introduction

LOVE

Katherine Mansfield

A Married Man’s Story

Dorothy Parker

A Telephone Call

Doris Lessing

A Man and Two Women

Doris Lessing

How I Finally Lost My Heart

Margaret Drabble

Faithful Lovers

Angela Carter

Master

Margaret Atwood

The Man from Mars

Angela Carter

The Bloody Chamber

Ellen Gilchrist

1944

Alice Walker

The Lover

Mavis Gallant

Rue de Lille

Carol Shields

Words

Anne Enright

Revenge

Elspeth Davie

Choirmaster

Alison Lurie

Ilse’s House

Alison Lurie

In the Shadow

Jennifer Egan

The Watch Trick

Jeanette Winterson

Atlantic Crossing

Clare Boylan

My Son the Hero

Maggie Gee

The Artist

Colette Paul

Kenny

Rachel Seiffert

Reach

Rachel Seiffert

Field Study

Yiyun Li

Love in the Marketplace

Nadine Gordimer

Mother Tongue

Miranda July

The Shared Patio

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Thing Around Your Neck

Carys Davies

The Redemption of Galen Pike

Alison MacLeod

The Heart of Denis Noble

Emma Donoghue

The Lost Seed

Roshi Fernando

The Turtle

M. J. Hyland

Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes

Emma Donoghue

The Gift

Avril Joy

Millie and Bird

LOSS

Katherine Mansfield

The Canary

Elizabeth Bowen

A Walk in the Woods

Dorothy Parker

Sentiment

Shirley Jackson

The Lottery

Flannery O’Connor

The Life You Save May Be Your Own

Elizabeth Taylor

The Blush

Anna Kavan

A Visit

Anna Kavan

Obsessional

Muriel Spark

The First Year of My Life

Ellen Gilchrist

Indignities

Penelope Lively

The Pill-Box

Alice Munro

Miles City, Montana

Carol Shields

Fragility

Margaret Drabble

The Merry Widow

A. M. Homes

The I of It

Marina Warner

The First Time

Nicola Barker

Inside Information

Penelope Fitzgerald

Desideratus

Lorrie Moore

Agnes of Iowa

Hilary Mantel

Curved is the Line of Beauty

Susan Hill

Father, Father

Colette Paul

Renaissance

Yiyun Li

After a Life

Helen Simpson

Sorry?

Helen Simpson

Up at a Villa

Edna O’Brien

Plunder

Edith Pearlman

Aunt Telephone

Emma Donoghue

Vanitas

Alice Munro

Gravel

Alice Munro

The Eye

Carrie Tiffany

Before He Left the Family

Lucy Wood

Diving Belles

THE LIVES OF WOMEN

Willa Cather

Consequences

Virginia Woolf

A Society

Ellen Gilchrist

Generous Pieces

Dorothy Parker

The Waltz

Doris Lessing

Through the Tunnel

Penelope Fitzgerald

The Axe

Margaret Atwood

Betty

Penelope Lively

A World of Her Own

Anita Desai

Sale

Alice Munro

Mischief

Elspeth Davie

Change of Face

Elspeth Davie

A Weight Problem

Penelope Fitzgerald

The Prescription

Alice Walker

How Did I Get Away with Killing One of the Biggest Lawyers in the State? It Was Easy.

Penelope Lively

Corruption

A. M. Homes

A Real Doll

A. M. Homes

Yours Truly

Anne Enright

(She Owns) Every Thing

Elizabeth Jolley

Waiting Room (The First)

Jane Gardam

Telegony I: Going into a Dark House

Alison Lurie

Fat People

Nicola Barker

G-String

Nicola Barker

Wesley: Blisters

Jennifer Egan

Emerald City

Muriel Spark

The Snobs

Hilary Mantel

Third Floor Rising

A. S. Byatt

The Thing in the Forest

Maggie Gee

Good People

Ali Smith

The Child

A. L. Kennedy

Story of My Life

Polly Samson

The Man Across the River

Helen Simpson

Ahead of the Pack

Stella Duffy

To Brixton Beach

About this Book

Also by Victoria Hislop

About Victoria Hislop

An Invitation from the Publisher

Copyright

Extended Copyright

Introduction

While gathering the short stories for this anthology, I have read some of the most brilliant and profound pieces of writing that I have ever come across.

The authors in this anthology range from a Nobel Prize winner, Doris Lessing, to the acknowledged queen of short stories, Alice Munro. There are Man Booker winners, Costa winners and Pulitzer winners. A few were born in the 19th century but the majority are more modern. Several of them are as yet unknown, others are household names, like Virginia Woolf. Many of the most vivid and passionate storytellers are young. And without doubt many of the most powerfully original are contemporary writers.

Apart from the writers all being female, the other guiding factor in the selection is that the stories have been written in English. The stories are varied and I am sure that no single reader will like them all. Perhaps I enjoyed certain stories because they meant something very personal to me. Others I think would be admired by any reader.

I discovered that it is possible for a short story (unlike a novel) to attain something close to perfection. Its brevity can mean that an author has the chance to produce a series of almost perfectly formed sentences, where every carefully chose

n word contributes to its meaning. Occasionally the result is flawless, something a novel can never be.

Readers are allowed to be impatient with short stories. My own patience limit for a novel which I am not hugely enjoying may be three or four chapters. If it has not engaged me by then, it has lost me and is returned to the library or taken to a charity shop. With a short story, three or four pages are the maximum I allow (sometimes they are only five or six pages long in any case). A short story can entice us in without preamble or background information, and for that reason it has no excuse. It must not bore us even for a second.

If a short story has no excuse for being dull, it has even less reason to be bland. As I selected the stories for this anthology, I found myself reading stories that made me laugh out loud, gasp and often weep. If a story did not arouse a strong response in me, then I did not select it. Even if it is elegaic or whimsical, it must still stir something deep in the pit of the stomach or make the heart race.

Some stories had such a strong effect on me that I had to put a collection down and do something different with the rest of my day. I could read nothing else. I needed to ponder it, or possibly read it for a second time. Muriel Spark’s ‘The First Year of My Life’ dazzled me with its brilliance. That was a day when I didn’t need to do anything other than reflect on her wisdom. For different reasons, Alice Munro’s ‘Miles City Montana’ rendered me incapable of continuing to read. She moves seamlessly from a description of a drowned boy’s funeral to an incident on a family outing where we believe that one of the children will drown. Even the relief I felt at the story’s relatively happy conclusion was not enough to lift my mood.

Quite often an anthology is named after the author’s favourite short story, and if that were the case I would read the eponymous story first. More often, there is no particular entry point into an anthology (unless you are happy to read them in the order they appear, something I usually resisted) and in that case, there was no better guide than simply whether the title intrigued me. Who, for example, would not go straight to a story entitled ‘How I Finally Lost My Heart’ (Doris Lessing), ‘A Weight Problem’ (Elspeth Davie), ‘How Did I Get Away with Killing One of the Biggest Lawyers in the State? It Was Easy.’ (Alice Walker) or even the intriguingly named: ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’ (Flannery O’Connor)?

A short story can be more surreal than many readers might tolerate with a novel and, perhaps, less grounded in reality. Succinctness sometimes allows a writer to explore ideas that may not sustain over a greater length. An example of this is Nicola Barker’s ‘Inside Information’, a shiningly original story told through the voice of an unborn child who is considering the suitability of its soon-to-be mother. Personally, I love the slightly quirky in a short story, but I would probably not be so patient if I had to listen to the voice of a foetus over three hundred pages.

I think the short story can give a writer the opportunity to experiment and to try a style or a voice that they would not use in the novel form, so there is often an element of freshness and surprise for the reader – and perhaps for the writer too.

For me, the stories that make the greatest impact are those that are the most emotional. On a few occasions, when I was reading in the library, I noted curious glances from my neighbours. They gave me sympathetic looks, but tactfully chose to ignore my tears, the context probably reassuring them that I was weeping over the fate of a fictional character rather than some personal catastrophe. Perhaps a few hours later, I would be shaking with suppressed laughter. I think I must have been a very annoying person with whom to share a desk.

I have divided the stories into three categories – Love, Loss and The Lives of Women – but these titles are loose.

Love is, of course, a central preoccupation of literature, but a love story is so often a story of loss, or indeed a story of life. Many of these stories take an amusing and sardonic look at love, so the division, though slightly artificial, is designed to give a reader the chance to read according to her or his mood. Many of them could appear under more than one heading and, I will admit, some stories could probably fit happily into all three categories.

LOVE

Love appears here in all its guises and disguises. As Yiyun Li describes in ‘Love in the Marketplace’: ‘A romance is more than a love story with a man.’

Perhaps maternal love is the most visceral of all loves. At least it felt so the first time I read the phenomenal ‘My Son the Hero’ by Clare Boylan. ‘Reach’ by Rachel Seiffert and ‘The Turtle’ by Roshi Fernando also powerfully evoke the strength of a mother’s love, and ‘Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes’ by M. J. Hyland touches beautifully on the love between father and son.

In this section there is the painful poignancy of romantic love in Margaret Drabble’s ‘Faithful Lovers’, love that is more like madness in ‘Master’ by Angela Carter and love that is unrecognised until it is too late in ‘The Man from Mars’ by Margaret Atwood. There is love that for some reason is not meant to be. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes about this in ‘The Thing Around your Neck’. There is love as infatuation, short-lived and potentially destructive, in Jennifer Egan’s ‘The Watch Trick’, and the making of love, sometimes kinkily, as in Anne Enright’s ‘Revenge’.

Many readers will know the experience of being haunted by an ex, and Alison Lurie writes vividly about the effect of lost or past loves in her characters’ lives (‘In the Shadow’ and also the even more extraordinary ‘Ilse’s House’).

LOSS

Many of the stories in Loss are tragic, some are shocking. All of them are emotional.

From Katherine Mansfield’s almost unbearably poignant ‘The Canary’, which is written with a feather-light touch, to Alice Munro’s ‘Gravel’, which is blunt to the point of brutality, I think few of these stories will leave readers cold.

There are lost lives, lost loves, lost innocence, a lost mother (Colette Paul’s ‘Renaissance’), lost breasts (Ellen Gilchrist’s ‘Indignities’), loss of hearing (Helen Simpson’s ‘Sorry?’) and even a lost leopard (Anna Kavan’s extraordinary ‘A Visit’).

‘The First Year of My Life’ by Muriel Spark takes the idea that babies are born omniscient and gradually lose their power and their knowledge. In this story, a baby is born in 1913, ‘in the very worst year that the world had ever seen so far’, and watches, dismayed, unsmiling, sardonic: ‘My teeth were coming through very nicely in my opinion, and well worth all the trouble I was put to in bringing them forth. I weighed twenty pounds. On all the world’s fighting fronts the men killed in action or dead of wounds numbered 8,538,315 and the warriors wounded and maimed were 21,219,452. With these figures in mind I sat up in my high chair and banged my spoon on the table.’

It is a profound story – a curious companion piece to others in the anthology in which the story is also told by a wise, all-knowing baby: Nicola Barker’s masterful ‘Inside Information’ and Ali Smith’s ‘The Child’ (in The Lives of Women) are especially engaging and fresh.

Carol Shields’ ‘Fragility’, with its hinterland story of a disabled child and a couple’s lost happiness, shares much of the pathos of Yiyun Li’s ‘After a Life’, in which a dying child lies incarcerated in a small apartment. Both stories are agonising to read. Lorrie Moore’s ‘Agnes of Iowa’ is similarly tragic but even more open-ended, with a couple doomed to live in perpetuity with their woes.

Susan Hill’s ‘Father, Father’, a story of two daughters ‘losing’ their father to a second wife, their step-mother, is insightful and real, a common situation faultlessly described.

THE LIVES OF WOMEN

Life provides infinite shades of light and dark and in this section there are many curious tales and unusual settings. There is a handful of stories that made me ask: What on earth gave her this idea? Where did this come from? One example is ‘The Axe’ by Penelope Fitzgerald. It is a chilling horror story that takes place in the deceptively banal environment of an office and describes what happens when a man finds h

is job has been ‘axed’. The narrator leaves us, as she should in such a story, with our hairs standing on end.

There is plenty of humour in this section and this is often provided by an unexpected or rather marvellous twist. ‘How Did I Get Away with Killing One of the Biggest Lawyers in the State? It Was Easy.’ by Alice Walker is flawless. And Penelope Lively’s ‘Corruption’ is too, with the most brilliant visual image perhaps of any story – where a judge, involved in a pornography trial, takes some of his ‘research papers’ on holiday. A gust of wind sends copies of the offending magazines flying around the beach to be gathered by innocent children and even a woman who, until this moment, has been flirting with the judge. It is brilliantly comic. I felt I was watching the action unfold scene by scene, just as if I was watching a film.

There is a mildly pornographic element too in A. M. Homes’ darkly comic ‘A Real Doll’. It’s almost about love, but more to do with sex. A boy uses his sister’s Barbie as a sex toy and all sorts of jealousies ensue (Ken has an opinion, naturally). It’s funny, outrageous and totally original.