Music For Chameleons

Truman Capote

TRUMAN CAPOTE

Music for Chameleons

Truman Capote was a native of New Orleans, where he was born on September 30, 1924. His first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, was an international literary success when first published in 1948, and accorded the author a prominent place among the writers of America’s postwar generation. He sustained this position subsequently with short-story collections (A Tree of Night, among others), novels and novellas (The Grass Harp and Break fast at Tiffany’s), some of the best travel writing of our time (Local Color), profiles and reportage that appeared originally in The New Yorker (The Duke in His Domain and The Muses Are Heard), a true crime masterpiece (In Cold Blood), several short memoirs about his childhood in the South (A Christmas Memory, The Thanksgiving Visitor, and One Christmas), two plays (The Grass Harp and House of Flowers), and two films (Beat the Devil and The Innocents).

Mr. Capote twice won the O. Henry Memorial Short Story Prize and was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He died in August 1984, shortly before his sixtieth birthday.

SECOND VINTAGE INTERNATIONAL EDITION, JULY 2012

Copyright © 1975, 1977, 1979, 1980 by Truman Capote

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1980.

The selections in this book have previously appeared in the following publications: Esquire, Interview magazine, McCall’s magazine and The New Yorker.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: The Condé Nast Publications, Inc.:

The Preface is reprinted courtesy of Vogue, copyright © 1979 by

The Condé Nast Publications, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Capote, Truman, 1924–1984

Music for chameleons/by Truman Capote.—1st Vintage international ed.

p. cm.

I. Title.

PS3505.A59M8 1994

813.’54—dc20 93-42198

eISBN: 978-0-345-80308-5

www.vintagebooks.com

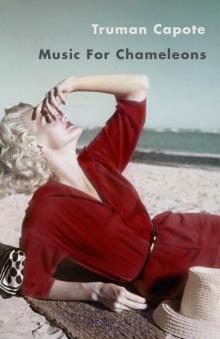

Cover design by Megan Wilson

Cover image © Condé Nast Archive/Corbis

v3.1_r1

For Tennessee Williams

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

I Music for Chameleons

One Music for Chameleons

Two Mr. Jones

Three A Lamp in a Window

Four Mojave

Five Hospitality

Six Dazzle

II Handcarved Coffins

A Nonfiction Account of an American Crime

III Conversational Portraits

One A Day’s Work

Two Hello, Stranger

Three Hidden Gardens

Four Derring-do

Five Then It All Came Down

Six A Beautiful Child

Seven Nocturnal Turnings

Other Books by This Author

Preface

MY LIFE—AS AN ARTIST, AT least—can be charted as precisely as a fever: the highs and lows, the very definite cycles.

I started writing when I was eight—out of the blue, uninspired by any example. I’d never known anyone who wrote; indeed, I knew few people who read. But the fact was, the only four things that interested me were: reading books, going to the movies, tap dancing, and drawing pictures. Then one day I started writing, not knowing that I had chained myself for life to a noble but merciless master. When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip; and the whip is intended solely for self-flagellation.

But of course I didn’t know that. I wrote adventure stories, murder mysteries, comedy skits, tales that had been told me by former slaves and Civil War veterans. It was a lot of fun—at first. It stopped being fun when I discovered the difference between good writing and bad, and then made an even more alarming discovery: the difference between very good writing and true art; it is subtle, but savage. And after that, the whip came down!

As certain young people practice the piano or the violin four and five hours a day, so I played with my papers and pens. Yet I never discussed my writing with anyone; if someone asked what I was up to all those hours, I told them I was doing my school homework. Actually, I never did any homework. My literary tasks kept me fully occupied: my apprenticeship at the altar of technique, craft; the devilish intricacies of paragraphing, punctuation, dialogue placement. Not to mention the grand overall design, the great demanding arc of middle-beginning-end. One had to learn so much, and from so many sources: not only from books, but from music, from painting, and just plain everyday observation.

In fact, the most interesting writing I did during those days was the plain everyday observations that I recorded in my journal. Descriptions of a neighbor. Long verbatim accounts of overheard conversations. Local gossip. A kind of reporting, a style of “seeing” and “hearing” that would later seriously influence me, though I was unaware of it then, for all my “formal” writing, the stuff that I polished and carefully typed, was more or less fictional.

By the time I was seventeen, I was an accomplished writer. Had I been a pianist, it would have been the moment for my first public concert. As it was, I decided I was ready to publish. I sent off stories to the principal literary quarterlies, as well as to the national magazines, which in those days published the best so-called “quality” fiction—Story, The New Yorker, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly—and stories by me duly appeared in those publications.

Then, in 1948, I published a novel: Other Voices, Other Rooms. It was well received critically, and was a best seller. It was also, due to an exotic photograph of the author on the dust jacket, the start of a certain notoriety that has kept close step with me these many years. Indeed, many people attributed the commercial success of the novel to the photograph. Others dismissed the book as though it were a freakish accident: “Amazing that anyone so young can write that well.” Amazing? I’d only been writing day in and day out for fourteen years! Still, the novel was a satisfying conclusion to the first cycle in my development.

A short novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, ended the second cycle in 1958. During the intervening ten years I experimented with almost every aspect of writing, attempting to conquer a variety of techniques, to achieve a technical virtuosity as strong and flexible as a fisherman’s net. Of course, I failed in several of the areas I invaded, but it is true that one learns more from a failure than one does from a success. I know I did, and later I was able to apply what I had learned to great advantage. Anyway, during that decade of exploration I wrote short-story collections (A Tree of Night, A Christmas Memory), essays and portraits (Local Color, Observations, the work contained in The Dogs Bark), plays (The Grass Harp, House of Flowers), film scripts (Beat the Devil, The Innocents), and a great deal of factual reportage, most of it for The New Yorker.

In fact, from the point of view of my creative destiny, the most interesting writing I did during the whole of this second phase first appeared in The New Yorker as a series of articles and subsequently as a book entitled The Muses Are Heard. It concerned the first cultural exchange between the U.S.S.R. and the U.S.A.: a tour, undertaken in 1955, of Russia by a company of black Americans in Porgy and Bess. I conceived of the whole adventure as a short comic “nonfiction novel,” the first.

Some years earlier, Lillian Ross had published Picture, her account of the making of a movie, The Red Badge of Courage; with its fast cuts, its flash forward and ba

ck, it was itself like a movie, and as I read it I wondered what would happen if the author let go of her hard linear straight-reporting discipline and handled her material as if it were fictional—would the book gain or lose? I decided, if the right subject came along, I’d like to give it a try: Porgy and Bess and Russia in the depths of winter seemed the right subject.

The Muses Are Heard received excellent reviews; even sources usually unfriendly to me were moved to praise it. Still, it did not attract any special notice, and the sales were moderate. Nevertheless, that book was an important event for me: while writing it, I realized I just might have found a solution to what had always been my greatest creative quandary.

For several years I had been increasingly drawn toward journalism as an art form in itself. I had two reasons. First, it didn’t seem to me that anything truly innovative had occurred in prose writing, or in writing generally, since the 1920s; second, journalism as art was almost virgin terrain, for the simple reason that very few literary artists ever wrote narrative journalism, and when they did, it took the form of travel essays or autobiography. The Muses Are Heard had set me to thinking on different lines altogether: I wanted to produce a journalistic novel, something on a large scale that would have the credibility of fact, the immediacy of film, the depth and freedom of prose, and the precision of poetry.

It was not until 1959 that some mysterious instinct directed me toward the subject—an obscure murder case in an isolated part of Kansas—and it was not until 1966 that I was able to publish the result, In Cold Blood.

In a story by Henry James, I think The Middle Years, his character, a writer in the shadows of maturity, laments: “We live in the dark, we do what we can, the rest is the madness of art.” Or words to that effect. Anyway, Mr. James is laying it on the line there; he’s telling us the truth. And the darkest part of the dark, the maddest part of the madness, is the relentless gambling involved. Writers, at least those who take genuine risks, who are willing to bite the bullet and walk the plank, have a lot in common with another breed of lonely men—the guys who make a living shooting pool and dealing cards. Many people thought I was crazy to spend six years wandering around the plains of Kansas; others rejected my whole concept of the “nonfiction novel” and pronounced it unworthy of a “serious” writer; Norman Mailer described it as a “failure of imagination”—meaning, I assume, that a novelist should be writing about something imaginary rather than about something real.

Yes, it was like playing high-stakes poker; for six nerve-shattering years I didn’t know whether I had a book or not. Those were long summers and freezing winters, but I just kept on dealing the cards, playing my hand as best I could. Then it turned out I did have a book. Several critics complained that “nonfiction novel” was a catch phrase, a hoax, and that there was nothing really original or new about what I had done. But there were those who felt differently, other writers who realized the value of my experiment and moved swiftly to put it to their own use—none more swiftly than Norman Mailer, who has made a lot of money and won a lot of prizes writing nonfiction novels (The Armies of the Night, Of a Fire on the Moon, The Executioner’s Song), although he has always been careful never to describe them as “nonfiction novels.” No matter; he is a good writer and a fine fellow and I’m grateful to have been of some small service to him.

The zigzag line charting my reputation as a writer had reached a healthy height, and I let it rest there before moving into my fourth, and what I expect will be my final, cycle. For four years, roughly from 1968 through 1972, I spent most of my time reading and selecting, rewriting and indexing my own letters, other people’s letters, my diaries and journals (which contain detailed accounts of hundreds of scenes and conversations) for the years 1943 through 1965. I intended to use much of this material in a book I had long been planning: a variation on the nonfiction novel. I called the book Answered Prayers, which is a quote from Saint Thérèse, who said: “More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.” In 1972 I began work on this book by writing the last chapter first (it’s always good to know where one’s going). Then I wrote the first chapter, “Unspoiled Monsters.” Then the fifth, “A Severe Insult to the Brain.” Then the seventh, “La Côte Basque.” I went on in this manner, writing different chapters out of sequence. I was able to do this only because the plot—or rather plots—was true, and all the characters were real: it wasn’t difficult to keep it all in mind, for I hadn’t invented anything. And yet Answered Prayers is not intended as any ordinary roman à clef, a form where facts are disguised as fiction. My intentions are the reverse: to remove disguises, not manufacture them.

In 1975 and 1976 I published four chapters of the book in Esquire magazine. This aroused anger in certain circles, where it was felt I was betraying confidences, mistreating friends and/or foes. I don’t intend to discuss this; the issue involves social politics, not artistic merit. I will say only that all a writer has to work with is the material he has gathered as the result of his own endeavor and observations, and he cannot be denied the right to use it. Condemn, but not deny.

However, I did stop working on Answered Prayers in September 1977, a fact that had nothing to do with any public reaction to those parts of the book already published. The halt happened because I was in a helluva lot of trouble: I was suffering a creative crisis and a personal one at the same time. As the latter was unrelated, or very little related, to the former, it is only necessary to remark on the creative chaos.

Now, torment though it was, I’m glad it happened; after all, it altered my entire comprehension of writing, my attitude toward art and life and the balance between the two, and my understanding of the difference between what is true and what is really true.

To begin with, I think most writers, even the best, overwrite. I prefer to underwrite. Simple, clear as a country creek. But I felt my writing was becoming too dense, that I was taking three pages to arrive at effects I ought to be able to achieve in a single paragraph. Again and again I read all that I had written of Answered Prayers, and I began to have doubts—not about the material or my approach, but about the texture of the writing itself. I reread In Cold Blood and had the same reaction: there were too many areas where I was not writing as well as I could, where I was not delivering the total potential. Slowly, but with accelerating alarm, I read every word I’d ever published, and decided that never, not once in my writing life, had I completely exploded all the energy and esthetic excitements that material contained. Even when it was good, I could see that I was never working with more than half, sometimes only a third, of the powers at my command. Why?

The answer, revealed to me after months of meditation, was simple but not very satisfying. Certainly it did nothing to lessen my depression; indeed, it thickened it. For the answer created an apparently unsolvable problem, and if I couldn’t solve it, I might as well quit writing. The problem was: how can a writer successfully combine within a single form—say the short story—all he knows about every other form of writing? For this was why my work was often insufficiently illuminated; the voltage was there, but by restricting myself to the techniques of whatever form I was working in, I was not using everything I knew about writing—all I’d learned from film scripts, plays, reportage, poetry, the short story, novellas, the novel. A writer ought to have all his colors, all his abilities available on the same palette for mingling (and, in suitable instances, simultaneous application). But how?

I returned to Answered Prayers. I removed one chapter and rewrote two others. An improvement, definitely an improvement. But the truth was, I had to go back to kindergarten. Here I was—off again on one of those grim gambles! But I was excited; I felt an invisible sun shining on me. Still, my first experiments were awkward. I truly felt like a child with a box of crayons.

From a technical point, the greatest difficulty I’d had in writing In Cold Blood was leaving myself completely out of it. Ordinarily, the reporter has to use himself as a character, an eyewitness observer, in ord

er to retain credibility. But I felt that it was essential to the seemingly detached tone of that book that the author should be absent. Actually, in all my reportage, I had tried to keep myself as invisible as possible.

Now, however, I set myself center stage, and reconstructed, in a severe, minimal manner, commonplace conversations with everyday people: the superintendent of my building, a masseur at the gym, an old school friend, my dentist. After writing hundreds of pages of this simpleminded sort of thing, I eventually developed a style. I had found a framework into which I could assimilate everything I knew about writing.

Later, using a modified version of this technique, I wrote a nonfiction short novel (Handcarved Coffins) and a number of short stories. The result is the present volume: Music for Chameleons.

And how has all this affected my other work-in-progress, Answered Prayers? Very considerably. Meanwhile, I’m here alone in my dark madness, all by myself with my deck of cards—and, of course, the whip God gave me.

—TRUMAN CAPOTE, 1979

PART ONE

Music for Chameleons

I

Music for Chameleons

SHE IS TALL AND SLENDER, perhaps seventy, silver-haired, soigné, neither black nor white, a pale golden rum color. She is a Martinique aristocrat who lives in Fort de France but also has an apartment in Paris. We are sitting on the terrace of her house, an airy, elegant house that looks as if it was made of wooden lace: it reminds me of certain old New Orleans houses. We are drinking iced mint tea slightly flavored with absinthe.

Three green chameleons race one another across the terrace; one pauses at Madame’s feet, flicking its forked tongue, and she comments: “Chameleons. Such exceptional creatures. The way they change color. Red. Yellow. Lime. Pink. Lavender. And did you know they are very fond of music?” She regards me with her fine black eyes. “You don’t believe me?”