Forsake the Sky

Tim Powers

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

FORSAKE THE SKY

Copyright © 1976. 1986 by Tim Powers

This edition has been revised from THE SKIES DISCROWNED, published by Laser Books. 1976.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

First printing: April 1986

A TOR Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates 49 West 24 Street New York. N.Y. 10010

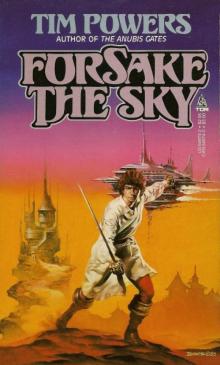

Cover art by Boris Vallejo

ISBN: 0-812-54973-2 CAN. ED.: 0-812-54974-0

Printed in the United States

0987654321

To Roy A. Squires

BOOK ONE: The Painter

Chapter 1

Dominion, it was called—a network that eventually encompassed a hundred stars in a field five thousand light-years across—and it was the most ambitious social experiment humans had ever embarked upon. It was a nation of more than a hundred planets, united by the Transport spaceships, the freighters that made possible the complex economic equations of supply and demand that kept the unthinkably vast Dominion empire running smoothly. Food from the fertile plains and seas of planets like Earth was shipped out to the worlds that produced ore, or vacuum-and-low-gravity industry, or simply provided office space; and the machinery and nutrients and pesticides from the manufactory worlds kept the farm worlds functioning at peak efficiency. Planetary independence was a necessity of the past—now no planet’s government need struggle to be self-sufficient; each world simply produced the things it was best suited to, and relied on the Transport ships to provide such necessities as were lacking.

For centuries Dominion was a healthy organism, nourished by its varied and widespread resources, which the bloodstream of the Transport ships distributed to all its parts.

FRANK Rovzar sat slouched against the back of the horse-drawn cart, hemmed in by a dozen hot, unhappy kitchen servants. They were all moaning and asking each other questions that none of them knew the answers to: Where are we going? What happened? Who are these people? Frank was the only silent one in the cart; he sat where he’d been thrown, staring intensely at nothing. From time to time he flexed his tightly bound wrists.

The cart rattled along southward on the Cromlech Road, making good time, for the Cromlech was one of the few highways on the planet that received regular maintenance. Within two hours of leaving the devastated palace they had arrived at the Barclay Transport Depot southwest of Munson, by the banks of the Malachi River. The cart, along with fifteen others like it, was taken through a gate in the chain-link fence that enclosed the depot, and across the wide, scorched concrete plain, and finally was brought to a halt in front of a bleak gray four-storey edifice.

Small-cargo scales had been dragged up from somewhere and now stood in a row by the doors. The bedraggled occupants of the carts were pulled and prodded out onto the pavement, weighed, lined up according to sex and mass, and then divided into groups and escorted into the building.

AFTER many centuries and dozens of local Golden Ages, Dominion began to weaken. It had expanded too rapidly, and the expected breakthroughs in faster-than-light communication and portable nuclear-fusion reactors simply never happened. Fossil fuels and Uranium-235 were inadequate in quantity and distribution. Transportation became increasingly expensive, and many things were no longer worth shipping. The smooth pulse of the import/export network had taken on a lurching, strained pace.

“NAME.” The officer’s voice had no intonation.

“Francisco de Goya Rovzar.”

“Age.”

“Twenty.”

“Occupation.”

“Uh ... apprentice painter.”

“Okay, Rovzar, step over there with the others.” Frank walked away from the desk and joined a crowd of other prisoners. The room they were in seemed calculated to induce depression. The floor was of damp cement, with drains set in at regular intervals; the paint was blistering off the pale green walls; the ceiling was corrugated aluminum, and naked light bulbs swung on the ends of long cords in the perpetual chilly draft.

The perfunctory interrogation continued until all the prisoners taken that morning had been questioned and stood in a milling, spiritless crowd. The officer who had been asking the questions now stood up and, flanked by two others who carried machine guns, faced the prisoners. He was short, with close-cropped sandy hair and a bristly moustache; his uniform was faultlessly neat.

“Give me your attention for a moment,” he said, unnecessarily. “You are here as prisoners of the Transport Authority, and of Costa, who two hours ago was confirmed as the new Duke of this planet. Ordinarily each of you would be allowed a court hearing in which to contest the charge of treason laid against you, but the entire planet of Octavio has, as of this morning, been declared to be under martial law.” He was reciting all this as dispassionately as a tired waiter announcing that the daily special is all gone. “When this condition is lifted you will be free to appeal your sentence. The sentence, like the crime, is the same for each of you: you are to be lifted tomorrow on a Transport freighter and ferried to the Orestes system to atone for your offenses in the uranium industry. Are there any questions?”

There were none. A few people laughed incredulously, for it was actually illegal for uranium miners to reenter normal society. Frank, his mind only now beginning to recover from the shock of his father’s murder, heard the sentence, but its irony, whether intentional or just negligent, was wasted on him. He filed the news away without thinking about it.

THE situation did not improve. Transportation became more and more sporadic and unreliable. Industrial planets were often left for weeks without food shipments, and agricultural planets were unable to replace broken machinery or obtain fuel for what worked. The Transport Company was losing its grip on the wide-flung empire; the outer sections were dying. Transport rates climbed, and the poorer planets, unable to maintain contact with the Dominion, were forced to drop out and try to survive alone. In time even the richest planets began working to be self-sufficient, in case the Transport Company should one day collapse entirely.

LATE that night Frank sat awake in the darkness of one of the depot detention pens. His cot and thin mattress were not particularly uncomfortable, but his thoughts were too vivid and alarming for him to sleep. The six other men in the pen with him apparently didn’t care to think, and slept deeply.

My father is dead, Frank told himself; but he couldn’t really believe it yet, not emotionally. Impressions of his father alive were too strong—he could still see the old man laughing over a mug of beer in a tavern, or sketching strangers’ faces in a pocket notebook, or shaking Frank awake in the predawn dimness so that they could gulp some coffee while they bundled up canvas and brushes and paints and thinners before getting on the horses and galloping off somewhere to catch a subject in the perfect light. Frank thought of how his life would be without old Rovzar to take care of, and he shied away from the lonely vision.

His destination was the Orestes mines. That was bad—about as bad as it could be. The mines riddled all four planets of the relatively young Orestes system, and working conditions ranged from desiccating desert heat to cold that could kill an exposed man in seconds. But the sovereign danger—and eventual certainty—was radiation poisoning. Panic grew in him as it became clear that he was about to be devastatingly punished by men who had never seen him before and were totally indifferent to him.

Only this morning—or was it now past midnight? Probably; only yesterday morning, then—he’d been playing with practice weapons at the Strand Fencing Academy. Now in this disinfectant-smelling darknes

s he wondered how he could have failed to see the shadow of the world’s true nature in the formalities of the stylized combat—the points and edges were imaginary, but the foils were models of a killing-tool ... a killing-tool every bit as real and routinely used as the pot in which a cook boils lobsters.

His father’s appointment with Duke Topo—Costa’s father—hadn’t been until noon, and the portrait his father was doing was well under way and needed no particular preparation from the apprentice, so Frank had strapped his foil and mask to the back of his saddle and ridden to Strand’s.

The place was just one room, but it was huge, a hundred feet by a hundred feet, with a ceiling so far above the floor that in decades no one had brushed the ropy cobwebs away from the very highest frames and trophies. A class was in session when Frank arrived, so he sat down on a bench between two of the tall windows and watched the sons of the aristocracy hop and plunge and flail about. He hoped it was a beginners’ class. The classes were getting bigger; a generation or two ago the young men were all taking shooting lessons.

When old Strand finally declared the lesson ended and told the students to pair off and bout with one another, and warned them which moves they weren’t to attempt yet, he walked over to Frank’s bench. “Hello, Frankie. Looking for a bout?”

“Yes sir. Is Tom around?”

“No, I sent the boy off on some errands. I’ll go around with you, though, if you like.”

“Well ... okay.”

It was always intimidating to fence with Tom’s father, for the old man would frequently halt a bout to point out, loudly, his opponent’s errors, and if the opponent managed to score even one touch against old Strand’s five it was a rare feat; but it was true too that one’s next opponent, no matter who it was, seemed much less daunting.

Frank was left-handed, and once they’d found a vacant strip, put on their masks and jackets, saluted and come on guard, he kept his blade well-extended in an exaggeratedly outside-twisted sixte position, for this pretty much forced the right-hander to attack into his inside line, and it was such a long way to reach that Frank could generally let an incoming blade come close enough to be totally committed before he parried, and thus he wasted a lot less effort—and exposure—trying to parry thrusts that turned out to be mere feints.

But it did little good against Tom’s father, who could, almost supernaturally, wait until the last split instant before deciding whether his attack was genuine, or just a feint to open Frank’s defenses for an attack somewhere else. Frank took four touches in two minutes, and his only consolation was that the old man once shouted “Not bad!” when a compound riposte of Frank’s nearly hit him.

After the fourth touch Strand stepped back. “Have you been practicing the Self-Inflicted Foot Thrust?” he asked. His voice, it seemed to Frank, was as relaxed as if he’d just now looked up from reading a book.

“Well,” Frank panted, “yeah—some.”

“Put me into it.”

“Okay.” Frank took a deep breath and then hopped backward, his sword raised; Strand beat it aside and advanced with a thrust; Frank caught the older man’s blade in a bind from below, whipped it upward with his own blade, and then flung it downward; but not only did Strand’s point fail to strike Strand’s own foot, as it would have if Frank had done the move correctly, but Strand’s blade had lashed back up, knocked Frank’s aside, and then darted in to flex firmly against Frank’s chest.

“Not yet, lad.” Strand laughed, flipping his mask back and stepping forward to shake hands. “But keep practicing it.”

“Yes sir.”

As Frank turned away he saw that Strand’s son Tom had returned sometime during the bout and was now grinning and shaking his head at him. “At least,” he called cheerfully to Frank, “you almost hit your own foot that time.”

“You want to fence,” Frank asked with a defiant smile, “or just stand there and criticize your betters?”

“Might as well play chess as fence with those foils," said Tom, nevertheless crossing to the weapons rack. “That kind of fencing’s got no bearing on real sword-fighting.” He spoke almost automatically, for this was just one more thrust in a long-standing argument between Tom and Frank. Tom was always emphasizing the combat aspects of the sport, and talking about edges and points and blood-channels. He insisted that, to have any real value, fencing should approximate as closely as possible the conditions of real sword-fighting: the weapons should be heavier, the boundary lines on the floor dispensed with, “off-target” touches acknowledged with some physical handicap like an imposed limp and a bleed-to-death time limit. Frank usually countered by pretending to agree enthusiastically and then going on to suggest that touched fencers be required to groan, too, and fall dramatically, and maybe splash some artificial blood on the touched spot.

Generally Frank refused to do any saber fencing with Tom, for the fencing master’s son tended to lean into the blows too much—even though Frank nearly always won, his back and arms would be welted afterward from hits that, though mistimed or delivered after valid hits of Frank’s, nevertheless stung; but today, with Tom still grinning reminiscently about Frank’s failure at the Self-Inflicted Foot Thrust, he wanted to beat him at something Tom considered worthwhile.

“Okay,” he said carelessly, “dig out a couple of sabers, then.”

Tom laughed in surprise. “All right! You want to lose at something that counts, eh?” He swerved toward the saber-and-épée cabinet, digging in his pocket for his keys.

“Something ... not too abstract,” said Frank. “Hell, you’d probably be good at chess, too, if you could always use pieces that were made to look like little people.”

Tom Strand had found the right key, and he unlocked the cabinet and swung its door open. “Well,” he began, his smile a little forced now, “at least—at least I—”

“And if they bleated when you knocked them over,” Frank went on, “like those little perforated cans they give to kids, where each one makes the noise of the animal whose picture’s on the outside. A bishop could, like, make praying noises when you tipped him over, and the queen could yell rape or something—”

Tom selected a saber and then looked at Frank. He was squinting in what Frank had come to recognize as his man-of-the-world style. “Take a flight a few thousand feet over Munson,” he advised. “The streets look as ordered and geometrical as a checkerboard. But then come down and look closer.” He whirled his saber through the air fast enough to make it whistle. “The universe is one big jungle, and you’ve got to—”

“I know,” said Frank wearily as he took a left-handed blade for himself, “become a jungle creature to survive. I bet you use camouflage-pattern condoms.”

Tom laughed delightedly, and then winked at Frank. “You think it’s my idea? They demand ’em.”

“Snake women you hang out with,” said Frank. “They’d like you even better with a set of rattles.”

The conversation deteriorated even further then as their friendship and humor smoothed over the momentary edginess, and soon they were masked and slashing enthusiastically at each other as they stamped back and forth along one of the fencing strips. Frank beat Tom in the first bout, and in the second one they lost track of the score and just fenced until Frank had to leave to meet his father and ride to the palace.

Tom Strand hadn’t, this time, wielded the saber as if he were trying to beat dust out of a carpet, and as Frank rode home he reflected that even Tom was beginning to realize that it could be a civilized sport.

SOMEONE in a nearby cell whimpered now in the darkness, and Frank wondered whether the man’s nightmare could possibly be worse than what he’d presently be waking up to. Frank remembered young Costa’s grunt of effort as he drove the blade of his dress sword into his own father’s belly; a civilized sport, he thought.

Chapter 2

Only in death had Topo, the old Duke, taken on any dignity in Frank’s eyes; before he was murdered by his son he had always seemed to be nothing mor

e than a caricature of a planetary duke—either draping his ludicrously fat body in multicolored jewelled robes in order to ride a gaudy float in a parade or to publicly sign some obscure proclamation, or disappearing into the Ducal Palace to indulge himself in his dining room and harem. Rumor had it that even in the harem the old Duke would not permit himself to be seen without a suitable tunic and turban; the more utilitarian of his visits there were said to be conducted in absolute darkness to preserve the dignity of his station.

When Frank’s father had begun doing the old Duke’s portrait two weeks ago, the old painter had jokingly suggested that the Duke pose nude. Frank, who’d been setting up the easel, actually thought for a moment that Topo was going to have his father flung out of the palace. The Duke had managed to swallow his rage, though, and then force a laugh and decline the offer, but it was lucky that Frank’s father had been in the early, blocking-in-with-pencil stage of the portrait, for Topo’s face didn’t lose its redness during that entire session.

Only at one other session had Frank’s father apparently deviated from strictly respectful professionalism; Frank wasn’t sure, for he didn’t understand the bit of dialogue he’d overheard when he returned, more quickly than usual, from a turpentine-fetching errand. On their way home that evening Frank had asked his father about it, but the old painter had just laughed and said he couldn’t discuss it, that it was a state secret. Frank had puzzled over it later. “Sure you don’t want me to make it either all-bird or all-girl?” his father had muttered quietly to the Duke, before either of them had noticed that Frank had returned. “I still could, you know.” The Duke had replied with some remark about a stretched canvas, and then saw Frank and hastily changed the subject.

The session yesterday, which had ended with the murders of Topo and old Rovzar, had begun ordinarily. The guards at the barbican gate had recognized the old painter and his son, and waved the pair on inside with sociably slack slingshots. The wait in front of the palace doors was perhaps a little longer than usual, but they were in the cool shadow of the wall, and the page who took their horse brought them a bucket of chilly beer and two wooden mugs when he returned, and they used the extra time to comb their sweaty hair and stamp some of the road dust off their boots.