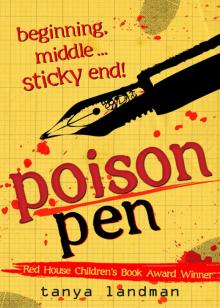

Poison Pen

Tanya Landman

For Daniel, John and every

cherub-faced child I’ve met

who’s possessed by a

gruesome imagination…

Table of Contents

Good Reads

Invisible Man

Death Threats?

Foul Play!

Nosebleed

Max Spectre

Zenith

The Old Boar

Killer Pigs

Collateral Damage

Press Attack!

Vampires

Death of a Ghost

The Pen is Mightier

Go West!

Fletcher, Beaumont & Grimm

Violas Confession

Death by Dragon

By 7 p.m. the London offices of Fletcher, Beaumont & Grimm were almost deserted. Almost, but not quite. In a book-lined study a reader sat behind a mahogany desk, turning the pages of a freshly typed manuscript. The silence was broken only by the occasional rustling of paper and the steady ticking of a grandfather clock. Across the room a leather armchair creaked as Sebastian Vincent, the manuscript’s author, shifted nervously, waiting for the reader’s response.

At last the wait was over. Sebastian watched as the final page was replaced carefully and smoothed with a sigh of satisfaction. That was a good sign, wasn’t it? He hoped so, after the blood, sweat and tears he had put into writing it!

The reader met his eye and nodded before saying, “This is a work of rare genius, Mr Vincent. Very many congratulations.”

Sebastian gulped. “You think you’ll publish it?”

“Oh yes. I will have to present it for approval at our next editorial meeting, but that’s a mere formality. Your book is thrilling. Unputdownable, as they say. There’s no doubt in my mind that you have a prize-winner here – a bestseller.” There was a pause and the reader’s eyes narrowed a fraction. “Tell me, Mr Vincent… Have you shown your book to anyone else? Any other publishers, for example? To anyone at all?”

Sebastian shook his head. It was true. He hadn’t shown it to anyone in the book world, at any rate. “I came straight to Fletcher, Beaumont & Grimm. I’d heard you were the best, you see.”

“Good. Very good.” The reader smiled and threw open the door of a well-stocked drinks cabinet. “Can I get you something?”

Sebastian looked uncomfortable. “I can’t. I’m on medication, you see.” He let out an awkward laugh. “A drink would be fatal!”

“Well, maybe an orange juice, then?”

“Thank you.”

Sebastian’s mind was dancing with glorious images: book signings with queues of adoring fans; literary festivals with eager readers hanging on his every word; TV and radio programmes with respectful critics asking for his opinion on the issues of the day. He swallowed his juice, not noticing its strangely bitter aftertaste, and then stood up to leave.

Still dreaming of a golden future, he shook the reader’s hand warmly. Sebastian smiled, and the grin didn’t leave his face as he was escorted through the maze of corridors to the front entrance. The moment the reader closed the door behind him, Sebastian pulled out his mobile and tapped in a number. He couldn’t wait to relay the good news.

“Well? What did they say?” demanded a voice at the other end of the phone. “Did they like it?”

Sebastian didn’t answer. He was suddenly doubled up with pain. He yelped. Gasped. Moaned. The phone fell from his hand.

“Sebastian? Seb? What’s happening?” The voice was shrill with panic. “Say something! Are you all right?”

Sebastian Vincent was as far from all right as it was possible for anyone to be. He writhed and convulsed, screaming – begging – for the pain to stop. And thirty seconds later it did. Thirty seconds later he was perfectly still.

Thirty seconds later Sebastian Vincent was curled on the pavement. Dead.

good reads

My name is Poppy Fields. When my friend Graham and I volunteered to help out at the local book festival, our school librarian told us it would “really make things come alive”. She solemnly swore that meeting authors would be exciting; that their characters would “come leaping off the page”.

She didn’t mean it literally.

But on the very first morning, a fictional being really did seem to spring out of a book. Weirder still, he appeared to have Evil Intentions towards his creator. Before long, authors were getting attacked left, right and centre – and Graham and I found ourselves slap-bang in the middle of another murder investigation.

We have Book Week at school every year and it’s normally a low-key sort of affair. Mrs Woodward, the librarian, puts up a few extra posters and the English department drags in a not-very-well-known author or poet to give creative writing sessions. It’s not what you’d call mind-blowingly thrilling stuff, and I wouldn’t have put meeting real live writers on my 10 Things To Do Before I Die list. But the idea of getting involved in the book festival was irresistible: Viola Boulder made sure of that.

Viola was the organizer of the brand new Good Reads Festival. She’d persuaded a load of well-known authors (and a whole bunch of lesser-known ones) to come to our town for an action-packed weekend of events. There were going to be Seriously Earnest talks for grown-ups, but she’d planned a load of fun stuff too: storytimes for the tiddly-tots and write-your-own-horror workshops for teenagers. When Mrs Woodward announced the whole thing in assembly, she was almost quivering with excitement.

“It’s a wonderful opportunity to meet first-class writers like Francisco Botticelli—”

She was interrupted by a small explosion of enthusiasm from the fantasy-lovers in the hall. Francisco Botticelli writes seriously long epics about dragons and trolls. You know the sort of stuff: innocent young boy must fight the forces of evil aided by a fire-breathing dragon and a few trusty gnomes. The baddie is supposed to be all-powerful but, surprise, surprise, after a few tearful death scenes with minor characters, the goodies win against overwhelming odds and everything’s fine until the next bumper volume comes along. His new one was called Dragons and Demons and it ran to a whopping 786 pages. Francisco Botticelli’s books are massive in every sense. Personally, I think they’re a health hazard. You wouldn’t want to read one in bed. I mean, if you fell asleep holding it, you could give yourself a nasty head injury.

Once the murmuring had died down, Mrs Woodward spoke again. “Another author I’m sure you’ll be looking forward to seeing is … Katie Bell.”

This time there was an outbreak of gasps and sighs. Katie Bell wrote pink, spangly books about LURVE. As far as I can see, they all have pretty much the same story-line: girl meets boy and they fall deeply in lurve, then girl and boy have argument and, after a lot of weeping and several boxes of tissues, girl and boy get back together for ever. Her current book was called Stupid Cupid and the cover had a heart with an arrow through the middle. I can’t quite see the fascination myself, but I reckon at least half the girls in school worship Katie Bell.

The librarian went on to explain that the opening event would be with Charlie Deadlock, author not only of the supremely popular football series featuring Sam the Striker, but also of The Spy Complex, a new novel that was hotly tipped to win prizes. Muriel Black, the author of Wizard Wheezes, a book about – you’ve guessed it – a mischievous group of young wizards at boarding school, would be doing an event on the Saturday. So would Basil Tamworth, who wrote pig tales like This Boar’s Life, involving Farmer Biggins and his herd of Gloucester Old Spots, all of which manage to miraculously avoid the usual porcine fate of being turned into sausages.

And, as if all that wasn’t enough, Mrs Woodward told us that Zenith would be there. There was a spontaneous outburst of singing and pelvic thrusting at the back of the hall. Zenith had been a rock star who’d had loads of nu

mber one hits with outrageously raunchy songs like Do It Now and Do It Again and Do It One More Time. She’d made the kind of pop videos that were embarrassing to watch if your gran was in the room. But then she’d adopted several children and gone weirdly spiritual: she was now a vegan who ate only pulses and drank only rainwater. She was getting pretty old. She’d had so many facelifts that her real eyebrows had disappeared into her hairline and she had to crayon on replacements. Zenith had written a book called Princess Peony and her Perfect Pony Petrushka. The cover was heavily pink, with lashings of sparkles. As Mrs Woodward said Zenith’s name, she sniffed as if she didn’t approve of either the singer or the book.

Then the librarian topped everything by announcing the festival’s Grand Finale. She was bursting with pride as she said, “I’ve saved the biggest name for last. Has anyone heard of Esmerelda Desiree?”

Screams. Roars. Whooping and cheering. A deafening outbreak of applause. Esmerelda Desiree. Glamorous author of the blockbuster, gazillion-bestselling The Vampiress of Venezia, which had recently been turned into a box-office-record-breaking movie. The woman was mega-famous. You’d have to have spent the last two years sitting under a stone, blindfolded and with extremely effective ear plugs, not to have heard of her.

Eventually, once the noise had died down enough for her to speak, Mrs Woodward revealed the reason for announcing the Good Reads Festival highlights. Viola Boulder wanted ten volunteers – student ambassadors, she called them – to help with the events.

“Anyone interested can come and put their name down at breaktime. It will be on a strictly first come, first served basis. And for those of you who aren’t able to volunteer or to attend the festival, don’t worry. I’ll make sure I obtain signed copies of the authors’ books for the school library.”

To be honest, I wasn’t an especially big fan of any of the writers she’d mentioned, but I was dead keen to meet them in the flesh. I mean, they had to be a pretty weird bunch. They must spend all day on their own dreaming up imaginary worlds – it’s not like a proper grown-up job, is it? I’m interested in human behaviour and I couldn’t help wondering if famous writers were like famous actors. I’d met a few of those and noticed that they seemed to need an audience: it was as if they only thought they existed if they could see themselves reflected in other people’s eyeballs. Were authors the same? Or were they shy, retiring creatures who only came out to talk in public if they were forced to? I couldn’t wait to find out.

As Graham and I went off to class at the end of assembly, I said to him, “I reckon we should volunteer.”

Graham stopped and looked at me suspiciously. “I didn’t realize you liked any of those writers.”

“I don’t. I just thought it might be fun.”

“Fun?” Graham looked unconvinced. “An ability to write doesn’t necessarily translate into an ability to perform,” he said, flashing me one of his blink-and-you-miss-it grins. “Remember the poets?”

“How could I forget?” During Book Week we’d had to sit through a reading from the local poetry circle. Poet after poet had intoned dirge-like offerings in strange sing-song voices full of Meaning and Significance. It had been bum-numbingly boring and had gone on for what seemed like for ever. “It won’t be like that,” I said confidently. “I bet they’ll all be really interesting. They’re big names, aren’t they? They’ve got to be good. We’ll go to the library at break.”

Graham and I spend a fair bit of time in the school library. It’s not that we’re book-obsessed, you understand. But in the winter – when the wind’s whistling across the playing fields and howling around the building – it’s nice and warm in there. And in the summer – when it’s baking hot and you’ve forgotten your suncream and the bigger kids are hogging all the shade – it’s nice and cool. Plus, you don’t have to put up with the football-crazed maniacs who love to accidentally-on-purpose shoot the ball at the head of anyone who strays too close to their game. According to Graham, a library is the cradle of civilization. He likes the computers and the reference section. I like staring out of the window. You get a bird’s-eye view from up there, so I can study the playground dramas and crises from a safe distance.

The library’s usually pretty quiet, but today, as soon as we rounded the corner, we could hear an unfamiliar babble of chatter. It seemed that I wasn’t the only one wanting to get up close to the visiting authors. The library was packed with would-be student ambassadors.

“Oh great,” I said, my heart sinking. “Looks like we’re too late.”

But fortunately our frequent visits to the library put us at an advantage. When we cornered a slightly harassed-looking Mrs Woodward in general fiction she gave us a friendly smile.

“Gosh, it’s busy in here today, isn’t it?” she said. “Amazing what a bit of fame can do to people’s enthusiasm for reading.”

I came straight to the point. “Can we be student ambassadors?”

Mrs Woodward’s smile broadened as she pushed her glasses to the end of her nose so she could examine us more closely. “I knew you two would volunteer! I took the liberty of putting your names at the top of the list – I thought I could rely on you both to be sensible. As you’re such keen readers, I think that’s only fair, don’t you?”

So that was that. We were officially designated as student ambassadors at the Good Reads Festival. According to Mrs Woodward we’d only need to meet a few authors and make the odd cup of tea. It wasn’t going to be demanding. A nice, easy weekend, I thought.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

invisible man

At precisely 7.45 a.m. on Saturday, Graham and I reported to the town hall. It was a vast Victorian building – all marble floors and oak panelling and massive rooms with high ceilings. The town council had deserted it for new, purpose-built offices years ago, and since then they’d rented it out for conferences and weddings and the occasional concert. It was the perfect venue for the Good Reads Festival.

Today was launch day. The whole thing was due to kick off at 11 a.m. with three simultaneous events: a celebrity chef would be doing a cooking demonstration in the café to promote his new book; there was a toddlers’ storytime in the central library next door; and for older kids there was a talk by Charlie Deadlock, the football guy. After that, there was going to be a buffet lunch for the chef and a host of other writers who were going on to do events in the afternoon and evening.

Graham was grumpy – he’d have preferred to spend the day in front of his computer. But I was quite excited. All those different characters to watch? This was going to be good.

An army of volunteers, including Mrs Woodward (“Call me Sue – we’re not in school now!”) had already gathered in the entrance hall by the time we arrived. We recognized some of the kids but none of them were in our year so we muttered hi and that was it.

The caterers were offloading supplies for the buffet. The staff from the local bookshop were falling over themselves (and each other) unpacking boxes and piling books high on tables. Someone was brushing down a Winnie the Pooh outfit for the toddlers’ events. Someone else was hastily sticking up posters of authors and their book jackets on every square millimetre of available wall – only she wasn’t doing it very well, so they were peeling off and fluttering to the floor as soon as her back was turned. It was all noise and chatter and chaos, and I couldn’t quite see how everything was going to get done on time.

Then Viola Boulder walked in and everyone fell silent.

The first thing I noticed about her was that she was aptly named. She had a vast bosom and wide hips, but there was nothing soft about any of her curves – she looked about as warm and cuddly as a lump of granite. She wore big, round glasses and no make-up and her greying hair was permed into a whippy-ice-cream formation and sprayed with so much lacquer you’d probably have grazed your knuckles if you knocked against it.

Viola was one of those women my mum would have said had “natural authority” and I would call “plain bossy”. The s

econd she arrived she began calling out names and ticking them off on her clipboard, handing out official badges and schedules detailing everyone’s tasks. Sue Woodward was down to set up tea and light refreshments for the authors. Graham and I were in charge of assembling their welcome packs.

Viola shooed a whole bunch of us down the corridor ahead of her.

“This is the writers’ green room,” she declared as we arrived at a set of heavy double doors. Pushing them open, she prodded us through one by one. “I want this room to be a haven of peace and tranquillity, and it will be strictly off limits to the General Public. My authors can get focussed here before their events. Afterwards, they will come here to relax and unwind. No one without official identification is allowed in. Naturally I’ll have security keeping an eye out, but you must remain constantly alert. If you see anyone who shouldn’t be in here, you must inform me. I will not permit my authors to be troubled by over-eager fans.”

Viola then went on to give us a serious talk about how we should all behave. According to her, writers were fragile, sensitive souls with easily crushable egos, who needed careful and delicate handling. One wrong word, one careless sentence, could stunt their creativity for weeks. I felt a weight of responsibility land heavily on my shoulders. Graham and I exchanged an apprehensive glance.

Once Viola had finished her speech, she directed me and Graham to a long folding table covered with piles of papers. Our first job was to assemble the welcome packs to hand out to the authors as they arrived. We were to man the table until 10.30 a.m. and then someone else would take over while we escorted Charlie Deadlock to his talk.

We got to work while Viola briefed the rest of the team. The packs consisted of a map of the town, hotel and restaurant details, the programme of events, official name badges – that kind of stuff. While Graham and I shoved papers into individually labelled cloth bags, we listened in on Viola’s instructions. They sounded remarkably complicated, involving projectors, PowerPoint presentations and microphones. Tim, the technician, was clearly going to have an extremely busy weekend.