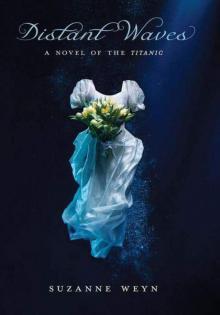

Distant Waves: A Novel of the Titanic: A Novel of the Titanic

Suzanne Weyn

Distant

Waves

A NOVEL

OF THE TITANIC

SUZANNE WEYN

SCHOLASTIC PRESS / NEW YORK

I have had three or four very striking and vivid premonitions in my life which have been fulfilled to the letter. I have others which await fulfilment. Of the latter, I will not speak here—although I have them duly recorded—for were I to do so I should be accused of being party to bringing about the fulfilment of my own predictions.

—W. T. Stead, famed British journalist who did not survive the sinking of the Titanic but predicted it

There are more things in heaven and earth…Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

—William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Table of Contents

Title Page

Epigraphs

Prologue

Chapter 1 NEW YORK CITY, 1898

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6 SPIRIT VALE, NEW YORK, 1898-1911

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14 SPIRIT VALE, 1911-1912

Chapter 15

Chapter 16 LONDON, APRIL 3, 1912

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36 NEW YORK CITY, AUGUST 1914

Chapter 37

Author's Note: WHAT'S REAL IN DISTANT WAVES?

Acknowledgments

Copyright

Prologue

APPROACHING NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA, 1914

Dear Friend,

I have never told this story before for fear of not being believed—or, worse, ridiculed. The strange circumstances of my childhood have inclined me to have faith in only that which can be proven by science or verified by research, yet this tale defies both methods of inquiry.

It is difficult to know where to start such a story as the one I am about to recount, but I believe my tale has its roots in events that all occurred on a single day in 1898, well before the even more remarkable happenings of 1912. The things that occurred in 1898 led me on a path that, as I look back on it now, seems predestined.

That day in my early childhood is emblazoned in my mind. All that I know about my life before that, I have been told by others. But the events of that most remarkable day I recall as though they had been photographed.

Now I am on a train headed toward Nova Scotia in Canada. I am propped against my suitcase writing this chronicle, partly in order to make sense of all that has happened, and partly to occupy my time and steady my nerves.

So much is at stake now.

My story, which I believe will have its final resolution in the next few hours, was set in motion on the day I witnessed my mother, Maude Taylor, in a spirit trance, contacting the dead for the very first time.

Chapter 1

NEW YORK CITY, 1898

I edged behind a burgundy drape as my mother raised her arms wide and began to sway rhythmically, eyes shut, head thrown back. An expression of earnest supplication suffused her delicate-featured face. Her reddish brown curls swung behind her. “Speak to me, Mary Adelaide Tredwell,” she intoned in her full, throaty voice. “Cease your lonely haunting of this house and come to us!”

She was seated at a round table. To her right were two middle-aged women, their hair plaited high on their heads, lace framing their hopeful faces. Owners of the house, they watched my mother with intense, expectant eyes. To her left was a balding, ill-at-ease man of about seventy.

“Your sisters, Gertrude and Julia, are here,” Mother went on. “They sense your presence in this house. They have heard your footsteps at night, noticed the furniture you have moved. Your husband, Mr. Richards, has joined us, as well. It is their dearest wish that you make yourself known to those of us present now.”

The luxurious drapes had been drawn, separating the white blast of afternoon light from the elegant, high-ceilinged room. In the deep alcove behind the curtains, I could turn toward the street to see life proceeding as usual: horse-drawn wagons trotting down cobblestoned streets and women walking with parasols to protect them from the blazing summer sun, their male partners properly attired in top hat and coat despite the heat. It was reassuring to be reminded that normal life was going on, especially when compared to the scene unfolding within the darkened parlor room.

I peered back through the break in the curtain and watched as my mother placed her hand on the table and told the others to do the same. “You have been haunting this house of your childhood, Mary Adelaide. Tarry no longer in the shadows of the afterlife. Those who have loved you in life wish to know you still.”

A soft hand not much larger than my own reached out to clutch my fingers. My sister Mimi had also been shaken by the eeriness of it all and had come behind the curtain to hide. Ever the protective one, she had pulled our twin two-year-old sisters, Amelie and Emma, asleep together in their large perambulator, behind the drape with her.

How old must we have been then? I am certain it was the summer of 1898, which would mean I had just turned four and Mimi was six.

Mimi’s large, amber brown eyes sparked with terror even as her heart-shaped face radiated its startling beauty. With the hand not holding mine, she nervously twisted one of her curly, raven black locks around her finger, a habit she would retain all her life.

Even though Mimi looked as terrified as I felt, it was a comfort to have my big sister there holding my hand. She might not be able to save me from any horror that could arise from this summoning of the dead, but even at that young age I was confident that she would never abandon me.

With my medium brown hair and more ordinary looks, I would always see myself as a plain brown sparrow next to her glossy beauty. But it never mattered. We were so close that I experienced her glory as simply a reason for sisterly pride.

A woman’s sharp gasp riveted us to the scene. The table had begun to tip, first to one side, and then to the other. The two women gazed at it, agape with horror. The man craned his neck below its top, searching for the source of this movement.

The tipping increased in speed. The banging of its three-legged pedestal as it lifted from side to side on the wooden parquet floor created an unsettling clatter. “Mary Adelaide!” Mother implored, nearly shouting. “Speak to us! Haunt this house no more with coy signs. Instead, let us hear you directly!”

“Yes, talk to us, Mary Adelaide!” cried one of the women. “It’s me! Gertrude!”

The table settled into a slow rocking. Mother stood, revealing the round, pregnant belly beneath her flowing vine-print dress.

Mimi’s crushing pressure on my hand would have made me cry out if what I was seeing had not already rendered me speechless.

Mother’s eyes grew wider than I had ever seen them. With her arms raised, she began to shiver as though a deep, bone-chilling frigidity had descended upon her.

I strained forward with an overwhelming impulse to wrap Mother in my arms and steady her violently convulsing frame, but Mimi’s grip held me b

ack. I beseeched Mimi with my eyes to let me go to our mother; surely this couldn’t be good for her or for the baby she was carrying. Mimi shook her head. “No, Jane,” she whispered. “Stay back.” She checked the sleeping twins with a darting glance, and retained her firm hold on my hand.

Mother’s eyes rolled back in their sockets as she threw her head back and shook it violently. Then, abruptly, her head snapped forward.

That beloved face, which I had until that moment experienced as being as familiar as my own, was completely transformed. It had grown timid, the eyes uncertain, furtive. Gone, too, was the confident, bold posture I associated with her. In its place was a willowy stance that had never been hers.

“Am I really back home?” she asked in a high, whispery voice, seeming confused. “Gertrude, Julia…is that you?”

“It’s us,” Gertrude volunteered eagerly.

“How old you’ve gotten!” Mother said with a gasp.

“It’s been twenty-four years since you died,” Julia pointed out.

“Has it?” Mother pressed her hand to her chest in a gesture of surprise I had never seen her use. “It seems to me that only a day has passed.” She turned slowly to the man at the table. “My dear, you’ve lost your hair,” she noted, and laughed lightly.

“This is a fraud!” the man shouted. “I’ll not stand for another second of it!” He pushed back from the table so fiercely that the chair he had been sitting on toppled behind him.

A squeal from the perambulator made Mimi and me turn sharply toward it. The clatter of the chair had stirred the twins from their sleep. Emma sputtered and fussed, then settled back to sleep. Amelie, though, sat forward, wide eyes locked in fascination on Mother.

Mother retained her lithe composure as Mr. Richards stormed out, slamming the door behind him. She bent toward Julia and Gertrude confidingly. “The spiritual realm has always made him ill at ease,” she said lightly, as if his departure was of little consequence. “He’s a captain of industry, and you know how they are.”

“Of course we know,” Julia said. “What man in our social circle is not?”

Mother looked at Julia, blinked hard, and wilted into her chair, her head bent down on her chest.

Again, I tried to go to her, and once more Mimi held on to me.

A white vapor, like steam from a boiling pot of water, rose behind Mother.

“What is that?” Gertrude asked, looking anxiously from Mother to Julia.

Amelie pointed, leaning so far out of the perambulator that I feared she would fall. I nudged Mimi and signaled for her to pull our baby sister in, which she did.

Mother lifted her head with great effort. “Julia, waste no time. It is short.”

Mother slumped forward on the table. This time I wouldn’t allow Mimi to hold me back. I raced out of my hiding place and went to her side, shaking her. “Mama! Mama!” I shouted. “Wake up! Wake up, please!”

Mother simply lay there, slumped over, not stirring.

Mimi threw the drapes aside, letting sunlight once more flood the room as Gertrude tried to rouse Mother with shakes and murmurs of solicitude. Julia poured a glass of water from the crystal decanter on the sideboard and brought it to her.

All the activity woke Emma, who reddened and began to cry heartily. Mimi rocked the perambulator, fruitlessly attempting to soothe her. Emma’s wails only increased, which turned out to be fortunate, since Mother lifted her head in response.

Relieved beyond measure that she was alive, I threw my arms around her. She stroked my hair and then rose as though everything was perfectly fine. Crossing the room, she lifted Emma from the perambulator and cradled her in the crook of her arm, rocking her gently. The crying stopped.

“Maude, you were magnificent!” Gertrude praised her.

“I have no doubt it was Mary Adelaide that we spoke to,” Julia added. “Every gesture and intonation was hers.”

Mother seemed bewildered for a moment. “You mean it happened?”

“Oh, yes!” Gertrude told her. “Weren’t you aware?”

Mother shook her head. “No, I…I suppose I…I must have passed out. When I awoke there at the table, I assumed I had fainted.”

I looked to Mimi, checking to see if she could make any sense of this. Mimi’s eyes had narrowed, and her delicate dark brows were in a ponderous V formation. Clearly she was as confused as I was, and was working hard to sort this out.

“Did you see into the spirit world while you were in your trance?” Gertrude asked Mother. “Did you see Mary Adelaide?”

“No, I did not see your sister,” Mother revealed as she sat on a velvet chair, still gently jiggling Emma. “She must have taken over my body and sent my spirit traveling elsewhere.”

“You certainly have the gift! I am so happy you have not been ne glecting the potential we saw you demonstrate as a girl!” Gertrude gushed.

Mother shook her head. “Not true.”

Gertrude cocked her head to the side in a gesture of confusion. “I don’t understand. You have been neglecting your gifts?”

Mother sighed and nodded. “You ladies know that as a young woman I showed great promise as a medium. When your family visited mine back in Hydesville, you saw the demonstration of my gifts.”

“I recall it well,” Julia said. “You were being mentored by Maggie Fox then—it’s so sad that she has passed over. People said that she and her sisters were frauds, but I never believed it.”

“Leah, the eldest, was a fraud, but Kate and Maggie had the gift,” Mother insisted.

I did not know it then, but I have since learned that the Fox sisters of Hydesville were famous spiritualists. When the ghost of a dead peddler who had once lived in their house and had stayed around to haunt it contacted them with strange raps and thumps, they became sensations, and started the movement known as spiritualism.

“We remembered you clearly,” Gertrude added. “You were so young and yet so impressive when you contacted the spirit of our dead president, Mr. Lincoln.”

“Mr. Lincoln was easy to find. He conducted séances in the White House, I am told. His wife was a believer,” Mother said.

“Don’t be so modest,” Gertrude chided. “I have never forgotten your gifts. That is why we sought you out when we needed to speak to Mary Adelaide. We were thrilled to discover you were living in Brooklyn.”

“That was indeed destiny, because I have only just arrived in Brooklyn from Massachusetts in the past month,” Mother said. “My stay with my mother-in-law is only temporary, God willing. I am at loose ends since the death of my beloved husband and must decide where to take up permanent residence.”

“I have of late come to hear about an entire community of spiritualists upstate, just south of Buffalo,” Julia Tredwell told Mother. “Now that you are a widow, perhaps it would be a hospitable environment in which to raise your daughters.”

“It sounds compelling,” Mother allowed.

Julia went to the sideboard and took out a pad and pencil. She wrote something on the paper and handed it to Mother.

Mother read the name on the pad and put it in a crochet bag she carried on her wrist. Holding Amelie in one arm and Emma in the other, she beckoned for Mimi and me to push the empty perambulator and follow her to the door. “Good day, ladies,” she said to Julia and Gertrude as the Tredwells’ butler held the door open for us. “Thank you so much for telling me about this town. It might be just the spot I have been seeking.”

“Your fee,” Julia reminded Mother, hurrying to drop an envelope in the purse.

“Oh, yes,” Mother said. “I’d nearly forgotten about it.”

“Maude, what do you think Mary Adelaide meant when she said my time was short?” Julia asked, her voice touched with a wavering tremble.

“I have no way to know,” Mother said softly. “But time is fleeting for all of us. It is advice we could all use.”

“Then why did she not say the same thing to Gertrude?” Julia asked. “Why did she address it to me, specifically

?”

Mother pressed Julia’s hands in her own. “The mysteries of life and death are as unknown to me as they are to you,” she said. “I’m sorry.”

When the door of the Tredwells’ brick row house was closed, Mother hurried us several buildings down the street. Only then did she stop to count the money in the envelope. A smile slowly spread across her face. “There’s money enough here for supper and train fare tomorrow,” she told us.

“A train? Where are we going?” Mimi asked.

“I’m not exactly sure at the moment,” Mother admitted, stroking her rounded belly. “We need to go somewhere so I can think about it more carefully.”

She didn’t know it, but we had already stepped on the path.

Chapter 2

Mother chose to think on a bench in nearby Washington Square Park. She arranged her billowing skirts discreetly over her pregnant frame and settled on one of the green park benches. “I’ll watch the twins, girls, but you two go for a stroll,” she said. “Mother needs a moment to meditate.”

The urban park’s open space with its imposing white arch, sparkling fountain, and winding cobblestoned paths was a perfectly agreeable spot in which to amble. Mimi and I meandered along, each of us lost in her own reverie.

I was thinking about everything that had happened in the last month: my father’s death from smallpox, our mother selling most of our belongings and moving us into Grandmother Taylor’s stately Brooklyn brownstone. I sensed without really knowing, as small children often do, that Mother was devastated not only about Father’s death but also about her current living conditions. She and Grandmother Taylor did not get on well.

We traveled the circumference of the park and then headed back to Mother on her bench. I’d always thought my mother made an imposing sight with her long skirt flowing around her. She was not exactly fat, but rather rounded, and now that she had a baby on the way, she was an even larger presence than usual.

Emma was toddling around in front of her, walking several steps and falling backward on her diapered bottom, then getting up to try again. Amelie sat languidly on the bench with her side melted against Mother’s, observing Emma’s exploits.