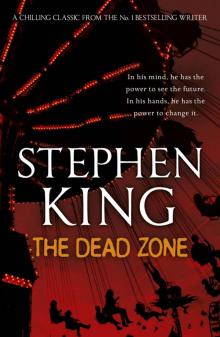

The Dead Zone

Stephen King

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

I - The Wheel of Fortune

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

II - The Laughing Tiger

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

III - Notes from the Dead Zone

Beware the Wheel of Fortune....

THE DEAD ZONE

Johnny, the small boy who skated at breakneck speed into an accident that for one horrifying moment plunged him into ... the dead zone.

Johnny Smith, the small-town schoolteacher who spun the wheel of fortune and won a trip into ... the dead zone.

John Smith, who awakened from a seemingly interminable coma with an accursed power: the power to see the future and the terrible fate awaiting mankind in ... the dead zone.

“Powerful tension holds the reader to the story like a pin to a magnet.”

—The Houston Post

WORKS BY STEPHEN KING

NOVELS

Carrie

’Salem’s Lot

The Shining

The Stand

The Dead Zone

Firestarter

Cujo

THE DARK TOWER I:

The Gunslinger

Christine

Pet Sematary

Cycle of the Werewolf

The Talisman

(with Peter Straub)

It

The Eyes of the Dragon

Misery

The Tommyknockers

THE DARK TOWER II:

The Drawing

of the Three

THE DARK TOWER III:

The Waste Lands

The Dark Half

Needful Things

Gerald’s Game

Dolores Claiborne

Insomnia

Rose Madder

Desperation

The Green Mile

THE DARK TOWER IV:

Wizard and Glass

Bag of Bones

The Girl Who Loved Tom

Gordon

Dreamcatcher

Black House

(with Peter Straub)

From a Buick 8

AS RICHARD BACHMAN

Rage

The Long Walk

Roadwork

The Running Man

Thinner

The Regulators

COLLECTIONS

Night Shift

Different Seasons

Skeleton Crew

Four Past Midnight

Nightmares and

Dreamscapes

Hearts in Atlantis

Everything’s Eventual

NONFICTION

Danse Macabre

On Writing

SCREENPLAYS

Creepshow

Cat’s Eye

Silver Bullet

Maximum Overdrive

Pet Sematary

Golden Years

Sleepwalkers

The Stand

The Shining

Rose Red

Storm of the Century

SIGNET

Published by New American Library, a division of

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd., 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd.)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty. Ltd.)

eISBN : 978-1-101-13814-4

Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd., 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty.) Ltd., 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

First Signet Printing, August 1980

Copyright © Stephen King, 1979

All rights reserved

The lyrics on page 64 are from “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” words and music by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Copyright © Northern Songs Ltd., 1968. All rights in the United States of America, Mexico, and the Philippines are controlled by Maclen Music, Inc., c/o ATV Music Corp. Used by permission. All rights reserved. The lyrics on pages 28 and 47 are from “Whole Lot-ta Shakin’ Goin’ On” by Dave Williams and Sonny David.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

http://us.penguingroup.com

AUTHOR’S NOTE

What follows is a work of fiction. All of the major characters are made up. Because it plays against the historical backdrop of the last decade, the reader may recognize certain actual figures who played their parts in the 1970s. It is my hope that none of these figures has been misrepresented. There is no third congressional district in New Hampshire and no town of Castle Rock in Maine. Chuck Chatsworth’s reading lesson is drawn from Fire Brain, by Max Brand, originally published by Dodd, Mead and Company, Inc.

THIS IS FOR OWEN I LOVE YOU, OLD BEAR

Prologue

1

By the time he graduated from college, John Smith had forgotten all about the bad fall he took on the ice that January day in 1953. In fact, he would have been hard put to remember it by the time he graduated from grammar school. And his mother and father never knew about it at all.

They were skating on a cleared patch of Runaround Pond in Durham. The bigger boys were playing hockey with old taped sticks and using a couple of potato baskets for goals. The little kids were just farting around the way little kids have done since time immemorial—their ankles bowing comically in and out, their breath puffing in the frosty twenty-degree air. At one corner of the cleared ice two rubb

er tires burned sootily, and a few parents sat nearby, watching their children. The age of the snowmobile was still distant and winter fun still consisted of exercising your body rather than a gasoline engine.

Johnny had walked down from his house, just over the Pownal line, with his skates hung over his shoulder. At six, he was a pretty fair skater. Not good enough to join in the big kids’ hockey games yet, but able to skate rings around most of the other first graders, who were always pinwheeling their arms for balance or sprawling on their butts.

Now he skated slowly around the outer edge of the clear patch, wishing he could go backward like Timmy Benedix, listening to the ice thud and crackle mysteriously under the snow cover farther out, also listening to the shouts of the hockey players, the rumble of a pulp truck crossing the bridge on its way to U.S. Gypsum in Lisbon Falls, the murmur of conversation from the adults. He was very glad to be alive on that cold, fair winter day. Nothing was wrong with him, nothing troubled his mind, he wanted nothing ... except to be able to skate backward, like Timmy Benedix.

He skated past the fire and saw that two or three of the grown-ups were passing around a bottle of booze.

“Gimme some of that!” he shouted to Chuck Spier, who was bundled up in a big lumberjack shirt and green flannel snowpants.

Chuck grinned at him. “Get outta here, kid, I hear your mother callin you.”

Grinning, six-year-old Johnny Smith skated on. And on the road side of the skating area, he saw Timmy Benedix himself coming down the slope, with his father behind him.

“Timmy!” he shouted. “Watch this!”

He turned around and began to skate clumsily backward. Without realizing it, he was skating into the area of the hockey game.

“Hey kid!” someone shouted. “Get out the way!”

Johnny didn’t hear. He was doing it! He was skating backward! He had caught the rhythm—all at once. It was in a kind of sway of the legs ...

He looked down, fascinated, to see what his legs were doing.

The big kids’ hockey puck, old and scarred and gouged around the edges, buzzed past him, unseen. One of the big kids, not a very good skater, was chasing it with what was almost a blind, headlong plunge.

Chuck Spier saw it coming. He rose to his feet and shouted, “Johnny! Watch out!”

John raised his head—and the next moment the clumsy skater, all one hundred and sixty pounds of him, crashed into little John Smith at full speed.

Johnny went flying, arms out. A bare moment later his head connected with the ice and he blacked out.

Blacked out ... black ice ... blacked out ... black ice ... black. Black.

They told him he had blacked out. All he was really sure of was that strange repeating thought and suddenly looking up at a circle of faces—scared hockey players, worried adults, curious little kids. Timmy Benedix smirking. Chuck Spier was holding him.

Black ice. Black.

“What?” Chuck asked. “Johnny ... you okay? You took a hell of a knock.”

“Black,” Johnny said gutturally. “Black ice. Don’t jump it no more, Chuck.”

Chuck looked around, a little scared, then back at Johnny. He touched the large knot that was rising on the boy’s forehead.

“I’m sorry,” the clumsy hockey player said. “I never even saw him. Little kids are supposed to stay away from the hockey. It’s the rules.” He looked around uncertainly for support.

“Johnny?” Chuck said. He didn’t like the look of Johnny’s eyes. They were dark and faraway, distant and cold. “Are you okay?”

“Don’t jump it no more,” Johnny said, unaware of what he was saying, thinking only of ice—black ice. “The explosion. The acid.”

“Think we ought to take him to the doctor?” Chuck asked Bill Gendron. “He don’t know what he’s sayin.”

“Give him a minute,” Bill advised.

They gave him a minute, and Johnny’s head did clear. “I’m okay,” he muttered. “Lemme up.” Timmy Benedix was still smirking, damn him. Johnny decided he would show Timmy a thing or two. He would be skating rings around Timmy by the end of the week ... backward and forward.

“You come on over and sit down by the fire for a while,” Chuck said. “You took a hell of a knock.”

Johnny let them help him over to the fire. The smell of melting rubber was strong and pungent, making him feel a little sick to his stomach. He had a headache. He felt the lump over his left eye curiously. It felt as though it stuck out a mile.

“Can you remember who you are and everything?” Bill asked.

“Sure. Sure I can. I’m okay.”

“Who’s your dad and mom?”

“Herb and Vera. Herb and Vera Smith.”

Bill and Chuck looked at each other and shrugged.

“I think he’s okay,” Chuck said, and then, for the third time, “but he sure took a hell of a knock, didn’t he? Wow.”

“Kids,” Bill said, looking fondly out at his eight-year-old twin girls, skating hand in hand, and then back at Johnny. “It probably would have killed a grown-up.”

“Not a Polack,” Chuck replied, and they both burst out laughing. The bottle of Bushmill’s began making its rounds again.

Ten minutes later Johnny was back out on the ice, his headache already fading, the knotted bruise standing out on his forehead like a weird brand. By the time he went home for lunch, he had forgotten all about the fall, and blacking out, in the joy of having discovered how to skate backward.

“God’s mercy!” Vera Smith said when she saw him. “How did you get that?”

“Fell down,” he said, and began to slurp up Campbell’s tomato soup.

“Are you all right, John?” she asked, touching it gently.

“Sure, Mom.” He was, too—except for the occasional bad dreams that came over the course of the next month or so ... the bad dreams and a tendency to sometimes get very dozy at times of the day when he had never been dozy before. And that stopped happening at about the same time the bad dreams stopped happening.

He was all right.

In mid-February, Chuck Spier got up one morning and found that the battery of his old ’48 De Soto was dead. He tried to jump it from his farm truck. As he attached the second clamp to the De Soto’s battery, it exploded in his face, showering him with fragments and corrosive battery acid. He lost an eye. Vera said it was God’s own mercy he hadn’t lost them both. Johnny thought it was a terrible tragedy and went with his father to visit Chuck in the Lewiston General Hospital a week after the accident. The sight of Big Chuck lying in that hospital bed, looking oddly wasted and small, had shaken Johnny badly—and that night he had dreamed it was him lying there.

From time to time in the years afterward, Johnny had hunches—he would know what the next record on the radio was going to be before the DJ played it, that sort of thing—but he never connected these with his accident on the ice. By then he had forgotten it.

And the hunches were never that startling, or even very frequent. It was not until the night of the county fair and the mask that anything very startling happened. Before the second accident.

Later, he thought of that often.

The thing with the Wheel of Fortune had happened before the second accident.

Like a warning from his own childhood.

2

The traveling salesman crisscrossed Nebraska and Iowa tirelessly under the burning sun in that summer of 1955. He sat behind the wheel of a ’53 Mercury sedan that already had better than seventy thousand miles on it. The Merc was developing a marked wheeze in the valves. He was a big man who still had the look of a comfed midwestern boy on him; in that summer of 1955, only four months after his Omaha house-painting business had gone broke, Greg Stillson was only twenty-two years old.

The trunk and the back seat of the Mercury were filled with cartons, and the cartons were filled with books. Most of them were Bibles. They came in all shapes and sizes. There was your basic item, The American TruthWay Bible, illustrated with sixteen c

olor plates, bound with airplane glue, for $1.69 and sure to hold together for at least ten months; then for the poorer pocketbook there was The American TruthWay New Testament for sixty-five cents, with no color plates but with the words of Our Lord Jesus printed in red; and for the big spender there was The American TruthWay Deluxe Word of God for $19.95, bound in imitation white leather, the owner’s name to be stenciled in gold leaf on the front cover, twenty-four color plates, and a section in the middle to note down births, marriages, and burials. And the Deluxe Word of God might remain in one piece for as long as two years. There was also a carton of paperbacks entitled America the TruthWay: The Communist-Jewish Conspiracy Against Our United States.

Greg did better with this paperback, printed on cheap pulp stock, than with all the Bibles put together. It told all about how the Rothschilds and the Roosevelts and the Greenblatts were taking over the U.S. economy and the U.S. government. There were graphs showing how the Jews related directly to the Communist-Marxist-Leninist-Trotskyite axis, and from there to the Antichrist Itself.

The days of McCarthyism were not long over in Washington; in the Midwest Joe McCarthy’s star had not yet set, and Margaret Chase Smith of Maine was known as “that bitch” for her famous Declaration of Conscience. In addition to the stuff about Communism, Greg Stillson’s rural farm constituency seemed to have a morbid interest in the idea that the Jews were running the world.

Now Greg turned into the dusty driveway of a farmhouse some twenty miles west of Ames, Iowa. It had a deserted, shut-up look to it—the shades down and the barn doors closed—but you could never tell until you tried. That motto had served Greg Stillson well in the two years or so since he and his mother had moved up to Omaha from Oklahoma. The house-painting business had been no great shakes, but he had needed to get the taste of Jesus out of his mouth for a little while, you should pardon the small blasphemy. But now he had come back home—not on the pulpit or revival side this time, though, and it was something of a relief to be out of the miracle business at last.