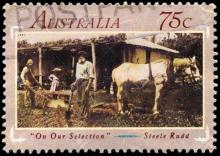

On Our Selection

Steele Rudd

Produced by Col Choat. HTML version by Al Haines.

On Our Selection

Steele Rudd (Arthur Hoey Davis)

PIONEERS OF AUSTRALIA!

To You "Who Gave Our Country Birth;" to the memory of You whose names, whose giant enterprise, whose deeds of fortitude and daring were never engraved on tablet or tombstone; to You who strove through the silences of the Bush-lands and made them ours; to You who delved and toiled in loneliness through the years that have faded away; to You who have no place in the history of our Country so far as it is yet written; to You who have done MOST for this Land; to You for whom few, in the march of settlement, in the turmoil of busy city life, now appear to care; and to you particularly, GOOD OLD DAD, This Book is most affectionately dedicated.

"STEELE RUDD."

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. STARTING THE SELECTION CHAPTER II. OUR FIRST HARVEST CHAPTER III. BEFORE WE GOT THE DEEDS CHAPTER IV. WHEN THE WOLF WAS AT THE DOOR CHAPTER V. THE NIGHT WE WATCHED FOR WALLABIES CHAPTER VI. GOOD OLD BESS CHAPTER VII. CRANKY JACK CHAPTER VIII. A KANGAROO HUNT FROM SHINGLE HUT CHAPTER IX. DAVE'S SNAKEBITE CHAPTER X. DAD AND THE DONOVANS CHAPTER XI. A SPLENDID YEAR FOR CORN CHAPTER XII. KATE'S WEDDING CHAPTER XIII. THE SUMMER OLD BOB DIED CHAPTER XIV. WHEN DAN CAME HOME CHAPTER XV. OUR CIRCUS CHAPTER XVI. WHEN JOE WAS IN CHARGE CHAPTER XVII. DAD'S "FORTUNE" CHAPTER XVIII. WE EMBARK IN THE BEAR INDUSTRY CHAPTER XIX. NELL AND NED CHAPTER XX THE COW WE BOUGHT CHAPTER XXI. THE PARSON AND THE SCONE CHAPTER XXII. CALLAGHAN'S COLT CHAPTER XXIII. THE AGRICULTURAL REPORTER CHAPTER XXIV. A LADY AT SHINGLE HUT CHAPTER XXV. THE MAN WITH THE BEAR-SKIN CAP CHAPTER XXVI. CHRISTMAS

On Our Selection.

Chapter I.

Starting the Selection.

It's twenty years ago now since we settled on the Creek. Twenty years!I remember well the day we came from Stanthorpe, on Jerome'sdray--eight of us, and all the things--beds, tubs, a bucket, the twocedar chairs with the pine bottoms and backs that Dad put in them, somepint-pots and old Crib. It was a scorching hot day, too--talk aboutthirst! At every creek we came to we drank till it stopped running.

Dad did n't travel up with us: he had gone some months before, to putup the house and dig the waterhole. It was a slabbed house, withshingled roof, and space enough for two rooms; but the partition wasn't up. The floor was earth; but Dad had a mixture of sand and freshcow-dung with which he used to keep it level. About once every monthhe would put it on; and everyone had to keep outside that day till itwas dry. There were no locks on the doors: pegs were put in to keepthem fast at night; and the slabs were not very close together, for wecould easily see through them anybody coming on horseback. Joe and Iused to play at counting the stars through the cracks in the roof.

The day after we arrived Dad took Mother and us out to see the paddockand the flat on the other side of the gully that he was going to clearfor cultivation. There was no fence round the paddock, but he pointedout on a tree the surveyor's marks, showing the boundary of our ground.It must have been fine land, the way Dad talked about it! There wasvery valuable timber on it, too, so he said; and he showed us a place,among some rocks on a ridge, where he was sure gold would be found, butwe were n't to say anything about it. Joe and I went back that eveningand turned over every stone on the ridge, but we did n't find any gold.

No mistake, it was a real wilderness--nothing but trees, "goannas,"dead timber, and bears; and the nearest house--Dwyer's--was three milesaway. I often wonder how the women stood it the first few years; and Ican remember how Mother, when she was alone, used to sit on a log,where the lane is now, and cry for hours. Lonely! It WAS lonely.

Dad soon talked about clearing a couple of acres and putting incorn--all of us did, in fact--till the work commenced. It was adelightful topic before we started,; but in two weeks the clusters offires that illumined the whooping bush in the night, and the crash uponcrash of the big trees as they fell, had lost all their poetry.

We toiled and toiled clearing those four acres, where the haystacks arenow standing, till every tree and sapling that had grown there wasdown. We thought then the worst was over; but how little we knew ofclearing land! Dad was never tired of calculating and telling us howmuch the crop would fetch if the ground could only be got ready in timeto put it in; so we laboured the harder.

With our combined male and female forces and the aid of a sapling leverwe rolled the thundering big logs together in the face of Hell's ownfires; and when there were no logs to roll it was tramp, tramp the daythrough, gathering armfuls of sticks, while the clothes clung to ourbacks with a muddy perspiration. Sometimes Dan and Dave would sit inthe shade beside the billy of water and gaze at the small patch thathad taken so long to do; then they would turn hopelessly to what wasbefore them and ask Dad (who would never take a spell) what was the useof thinking of ever getting such a place cleared? And when Dave wantedto know why Dad did n't take up a place on the plain, where there wereno trees to grub and plenty of water, Dad would cough as if somethingwas sticking in his throat, and then curse terribly about the squattersand political jobbery. He would soon cool down, though, and get hopefulagain.

"Look at the Dwyers," he'd say; "from ten acres of wheat they gotseventy pounds last year, besides feed for the fowls; they've got cornin now, and there's only the two."

It was n't only burning off! Whenever there came a short drought thewaterhole was sure to run dry; then it was take turns to carry waterfrom the springs--about two miles. We had no draught horse, and if wehad there was neither water-cask, trolly, nor dray; so we humpedit--and talk about a drag! By the time you returned, if you had n'tdrained the bucket, in spite of the big drink you'd take before leavingthe springs, more than half would certainly be spilt through the vesselbumping against your leg every time you stumbled in the long grass.Somehow, none of us liked carrying water. We would sooner keep thefires going all day without dinner than do a trip to the springs.

One hot, thirsty day it was Joe's turn with the bucket, and he managedto get back without spilling very much. We were all pleased becausethere was enough left after the tea had been made to give each a drink.Dinner was nearly over; Dan had finished, and was taking it easy on thesofa, when Joe said:

"I say, Dad, what's a nater-dog like?" Dad told him: "Yellow, sharpears and bushy tail."

"Those muster bin some then thet I seen--I do n't know 'bout the bushytail--all th' hair had comed off." "Where'd y' see them, Joe?" weasked. "Down 'n th' springs floating about--dead."

Then everyone seemed to think hard and look at the tea. I did n't wantany more. Dan jumped off the sofa and went outside; and Dad lookedafter Mother.

At last the four acres--excepting the biggest of the iron-bark treesand about fifty stumps--were pretty well cleared; and then came aproblem that could n't be worked-out on a draught-board. I havealready said that we had n't any draught horses; indeed, the only thingon the selection like a horse was an old "tuppy" mare that Dad used tostraddle. The date of her foaling went further back than Dad's, Ibelieve; and she was shaped something like an alderman. We found herone day in about eighteen inches of mud, with both eyes picked out bythe crows, and her hide bearing evidence that a feathery tribe had madea roost of her carcase. Plainly, there was no chance of breaking upthe ground with her help. We had no plough, either; how then was thecorn to be put in? That was the question.

Dan and Dave sat outside in the corner of the chimney, both scratchingthe ground with a chip and not saying anything. Dad and Mother satinside talking it over. Sometimes Dad would get up and walk round theroom shaking his head; then he would kick old Crib for lying under thetable. At last Mother struck something which brightened him

up, and hecalled Dave.

"Catch Topsy and--" He paused because he remembered the old mare wasdead.

"Run over and ask Mister Dwyer to lend me three hoes."

Dave went; Dwyer lent the hoes; and the problem was solved. That washow we started.