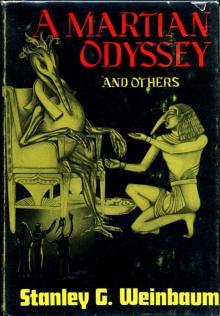

A Martian Odyssey

Stanley Grauman Weinbaum

Produced by Greg Weeks, Joel Schlosberg and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This eBook was produced from the 1949 book _A Martian Odyssey andOthers_ by Stanley G. Weinbaum, pp. 1-27. Extensive research did notuncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication wasrenewed.

A MARTIAN ODYSSEY

Jarvis stretched himself as luxuriously as he could in the crampedgeneral quarters of the _Ares_.

"Air you can breathe!" he exulted. "It feels as thick as soup after thethin stuff out there!" He nodded at the Martian landscape stretchingflat and desolate in the light of the nearer moon, beyond the glass ofthe port.

The other three stared at him sympathetically--Putz, the engineer,Leroy, the biologist, and Harrison, the astronomer and captain of theexpedition. Dick Jarvis was chemist of the famous crew, the _Ares_expedition, first human beings to set foot on the mysterious neighbor ofthe earth, the planet Mars. This, of course, was in the old days, lessthan twenty years after the mad American Doheny perfected the atomicblast at the cost of his life, and only a decade after the equally madCardoza rode on it to the moon. They were true pioneers, these four ofthe _Ares_. Except for a half-dozen moon expeditions and the ill-fatedde Lancey flight aimed at the seductive orb of Venus, they were thefirst men to feel other gravity than earth's, and certainly the firstsuccessful crew to leave the earth-moon system. And they deserved thatsuccess when one considers the difficulties and discomforts--the monthsspent in acclimatization chambers back on earth, learning to breathe theair as tenuous as that of Mars, the challenging of the void in the tinyrocket driven by the cranky reaction motors of the twenty-first century,and mostly the facing of an absolutely unknown world.

Jarvis stretched and fingered the raw and peeling tip of hisfrost-bitten nose. He sighed again contentedly.

"Well," exploded Harrison abruptly, "are we going to hear what happened?You set out all shipshape in an auxiliary rocket, we don't get a peepfor ten days, and finally Putz here picks you out of a lunatic ant-heapwith a freak ostrich as your pal! Spill it, man!"

"Speel?" queried Leroy perplexedly. "Speel what?"

"He means '_spiel_'," explained Putz soberly. "It iss to tell."

Jarvis met Harrison's amused glance without the shadow of a smile."That's right, Karl," he said in grave agreement with Putz. "_Ich spieles!_" He grunted comfortably and began.

"According to orders," he said, "I watched Karl here take off toward theNorth, and then I got into my flying sweat-box and headed South. You'llremember, Cap--we had orders not to land, but just scout about forpoints of interest. I set the two cameras clicking and buzzed along,riding pretty high--about two thousand feet--for a couple of reasons.First, it gave the cameras a greater field, and second, the under-jetstravel so far in this half-vacuum they call air here that they stir updust if you move low."

"We know all that from Putz," grunted Harrison. "I wish you'd saved thefilms, though. They'd have paid the cost of this junket; remember howthe public mobbed the first moon pictures?"

"The films are safe," retorted Jarvis. "Well," he resumed, "as I said, Ibuzzed along at a pretty good clip; just as we figured, the wingshaven't much lift in this air at less than a hundred miles per hour, andeven then I had to use the under-jets.

"So, with the speed and the altitude and the blurring caused by theunder-jets, the seeing wasn't any too good. I could see enough, though,to distinguish that what I sailed over was just more of this grey plainthat we'd been examining the whole week since our landing--same blobbygrowths and the same eternal carpet of crawling little plant-animals, orbiopods, as Leroy calls them. So I sailed along, calling back myposition every hour as instructed, and not knowing whether you heardme."

"I did!" snapped Harrison.

"A hundred and fifty miles south," continued Jarvis imperturbably, "thesurface changed to a sort of low plateau, nothing but desert andorange-tinted sand. I figured that we were right in our guess, then,and this grey plain we dropped on was really the Mare Cimmerium whichwould make my orange desert the region called Xanthus. If I were right,I ought to hit another grey plain, the Mare Chronium in another coupleof hundred miles, and then another orange desert, Thyle I or II. And soI did."

"Putz verified our position a week and a half ago!" grumbled thecaptain. "Let's get to the point."

"Coming!" remarked Jarvis. "Twenty miles into Thyle--believe it ornot--I crossed a canal!"

"Putz photographed a hundred! Let's hear something new!"

"And did he also see a city?"

"Twenty of 'em, if you call those heaps of mud cities!"

"Well," observed Jarvis, "from here on I'll be telling a few things Putzdidn't see!" He rubbed his tingling nose, and continued. "I knew that Ihad sixteen hours of daylight at this season, so eight hours--eighthundred miles--from here, I decided to turn back. I was still overThyle, whether I or II I'm not sure, not more than twenty-five milesinto it. And right there, Putz's pet motor quit!"

"Quit? How?" Putz was solicitous.

"The atomic blast got weak. I started losing altitude right away, andsuddenly there I was with a thump right in the middle of Thyle! Smashedmy nose on the window, too!" He rubbed the injured member ruefully.

"Did you maybe try vashing der combustion chamber mit acid sulphuric?"inquired Putz. "Sometimes der lead giffs a secondary radiation--"

"Naw!" said Jarvis disgustedly. "I wouldn't try that, of course--notmore than ten times! Besides, the bump flattened the landing gear andbusted off the under-jets. Suppose I got the thing working--what then?Ten miles with the blast coming right out of the bottom and I'd havemelted the floor from under me!" He rubbed his nose again. "Lucky for mea pound only weighs seven ounces here, or I'd have been mashed flat!"

"I could have fixed!" ejaculated the engineer. "I bet it vas notserious."

"Probably not," agreed Jarvis sarcastically. "Only it wouldn't fly.Nothing serious, but I had my choice of waiting to be picked up ortrying to walk back--eight hundred miles, and perhaps twenty days beforewe had to leave! Forty miles a day! Well," he concluded, "I chose towalk. Just as much chance of being picked up, and it kept me busy."

"We'd have found you," said Harrison.

"No doubt. Anyway, I rigged up a harness from some seat straps, and putthe water tank on my back, took a cartridge belt and revolver, and someiron rations, and started out."

"Water tank!" exclaimed the little biologist, Leroy. "She weighone-quarter ton!"

"Wasn't full. Weighed about two hundred and fifty pounds earth-weight,which is eighty-five here. Then, besides, my own personal two hundredand ten pounds is only seventy on Mars, so, tank and all, I grossed ahundred and fifty-five, or fifty-five pounds less than my everydayearth-weight. I figured on that when I undertook the forty-mile dailystroll. Oh--of course I took a thermo-skin sleeping bag for these wintryMartian nights.

"Off I went, bouncing along pretty quickly. Eight hours of daylightmeant twenty miles or more. It got tiresome, of course--plugging alongover a soft sand desert with nothing to see, not even Leroy's crawlingbiopods. But an hour or so brought me to the canal--just a dry ditchabout four hundred feet wide, and straight as a railroad on its owncompany map.

"There'd been water in it sometime, though. The ditch was covered withwhat looked like a nice green lawn. Only, as I approached, the lawnmoved out of my way!"

"Eh?" said Leroy.

"Yeah, it was a relative of your biopods. I caught one--a littlegrass-like blade about as long as my finger, with two thin, stemmylegs."

"He is where?" Leroy was eager.

"He is let go! I had to move, so I plowed along with the walking grassopening in front and closing behind. And then I was out on the orangedesert of Thyle again

.

"I plugged steadily along, cussing the sand that made going so tiresome,and, incidentally, cussing that cranky motor of yours, Karl. It was justbefore twilight that I reached the edge of Thyle, and looked down overthe gray Mare Chronium. And I knew there was seventy-five miles of_that_ to be walked over, and then a couple of hundred miles of thatXanthus desert, and about as much more Mare Cimmerium. Was I pleased? Istarted cussing you fellows for not picking me up!"

"We were trying, you sap!" said Harrison.

"That didn't help.