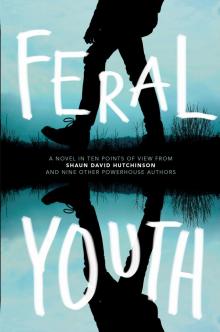

Feral Youth

Shaun David Hutchinson

Praise for Violent Ends

“An intriguing, powerful narrative . . . The storytelling is wonderfully intense and distinctive on such a difficult, tragic topic. Readers will be captivated.”

—VOYA, starred review

“Provocatively and effectively illustrates the multidimensionality of someone considered to be a monster . . . Engaging and heart-wrenching.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A fresh and thought-provoking take on a disturbing but relevant topic.”

—School Library Journal

Praise for At the Edge of the Universe

“An earthy, existential coming-of-age gem.”

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“Wrenching and thought-provoking, Hutchinson has penned another winner.”

—Booklist

Praise for We Are the Ants

“Hutchinson has crafted an unflinching portrait of the pain and confusion of young love and loss, thoughtfully exploring topics like dementia, abuse, sexuality, and suicide as they entwine with the messy work of growing up.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Bitterly funny, with a ray of hope amid bleakness.”

—Kirkus Reviews, starred review

“A beautiful, masterfully told story by someone who is at the top of his craft.”

—Lambda Literary

“Shaun David Hutchinson’s bracingly smart and unusual YA novel blends existential despair with exploding planets.”

—Shelf Awareness, starred review

Praise for The Five Stages of Andrew Brawley

“A writer to watch.”

—Booklist

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

I’M NOT A LIAR. You’re a liar. I’m just telling stories; that’s all. And sometimes when you’re telling a story, you can’t let stupid shit like the truth get in the way.

Besides, what good is the truth for anyway? Folks get put in prison for shit they didn’t do every single day, and telling the truth doesn’t help them one bit. Ask any woman who’s ever reported a sexual assault, and she’ll tell you how much the truth is worth. Nothing. The truth isn’t worth a damned thing. Only what people believe. And the funny thing is that most of the time, the story being told and how the person’s telling it isn’t as important as who’s doing the telling. Ask any black person who’s ever gone up against the police, and they’ll tell you.

Nah. There’s no such thing as an objective truth anymore. It’s all about what you believe. Believe something hard enough and—to you at least—that’s the truth forever and ever, and fuck anyone who tries to tell you otherwise.

Take these stories. I don’t know if they’re true or not, but I bet the ones doing the telling believe them. And that’s kind of all that matters. Whether a story is true isn’t important if you’re hurting all the same because of it.

Regardless, I’m going to tell you the truth. Not my truth, not their truths. The truth. The truth about the three days we spent alone in the woods, trying to hike back to Zeppelin Bend. How one broke their leg, how others fought, how we all nearly died, and how we managed to get our shit together and make it back alive.

Believe it or don’t. Makes no difference to me.

DAY 1

RECIPE FOR A CLUSTERFUCK: take ten teenagers the world believes are human garbage, toss in some hippy work-together-to-make-the-world-better bullshit, add a dash of insecurity and a dollop of fear, and then send the kids into the woods for three days and expect them not to kill and eat each other. Voilà! One glorious clusterfuck.

Zeppelin Bend isn’t one of those summer camps where campers spend their time finger painting and canoeing and singing songs. It’s the kind of place they send kids no one else wants and tell us it’s our last chance to make a U-turn before we wind up in juvie until we’re eighteen. Before Doug (which is the kind of name a parent gives their kid when they expect he’s going to turn out to be a massive asshole) drove us into the woods blindfolded, kicked us out of the van, and told us we had three days to hike back to Zeppelin Bend on our own, we spent three weeks learning how to use a compass, find food that wouldn’t kill us, start a fire without a lighter, and run from bears—since that’s really all you can do if a bear comes your way. In short, we supposedly learned all the skills necessary for a bunch of delinquents like us to survive. Doug even told us we’d get a surprise if we made it back to the Bend by the end of the third day. I figured it was probably an ice cream party or some other stupid bullshit, but even that sounded good after weeks of plain oatmeal and whatever chunky meat was in the stews they served for dinner.

It was just after sunrise when Doug marooned us in the woods, and we spent the first hour arguing over who was going to be in charge. Every group needs a leader, and everyone thinks it should be them. Everyone but me, anyway. I hung in the background, waiting to see who was going to come out on top. No use picking sides if you’re just going to pick the losing one. But eventually, we were going to have to choose someone, and I didn’t think it mattered who because, like I said, we were a recipe for a clusterfuck, and even the best chefs break a few eggs.

* * *

I guess I should tell you what I know about the others. Most of it’s shit I picked up around the Bend, so I can’t vouch for the truth of it. That’s why I like stories. They usually wind up revealing more about a person than what they’d tell you about themselves. It’s not that they lie intentionally, but when people describe themselves they’re really describing what they see in a mirror, and most mirrors are too distorted to show us the truth. If you listen hard enough, there’s more truth in fiction than in all the other shit combined.

Jackie Armstrong was the first person I met after my uncle dropped me off at the Bend. She’s kind of invisible in the way girls like her often are, and she was wearing a T-shirt with a logo from that werewolves in space TV show Space Howl. That was before we all got told we had to wear these shitty brown uniforms. It’s easy to dismiss a girl like Jackie, but you’re an idiot if you do.

Then there’s Tino Estevez. We got a lot in common, mostly being we’re both Mexican. Well, I’m mixed and he’s not, but it’s something. The kid’s kind of quiet, but if you watch him real hard, you can see some anger bubbling there under the surface. Before we’d even been dumped in the woods, my money was on him clocking someone before we were done. He kind of thought he should be the leader, but he wasn’t ready to fight for it hard enough.

Now, Jaila Davis is one badass motherfucker. She’s like a foot shorter than anyone else, but she acts like she’s a foot taller. I thought she was stuck-up when I first met her, but she’s probably better equipped to spend three days in the woods than anyone else in our dysfunctional group. And I don’t know how many languages she speaks, but she cusses in at least three.

David Kim Park was another one who thought he should be the leader, which was hilarious. The kid couldn’t navigate his way out of a paper bag, and he’s obsessed with sex. No lie. Anytime someone was like “Where’s David?” chances are he was hiding somewhere beating off. It was so bad, Doug had to pull him aside and talk to him about it twice. Plus

, David was convinced there was a Bigfoot or aliens or something in the woods.

The third of the J girls was Jenna Cantor. I basically pegged her as a rich white girl from day one, and she didn’t do much to prove me wrong while we were at the Bend. She was kind of weird, too. Aside from being able to do calculations in her head I couldn’t figure with a calculator, she was real quiet. But not like snobby quiet. More like she was living in a world the rest of us couldn’t see.

Lucinda Banks wore her anger on her uniform. I tried to figure out why she’d been sent to the Bend, but she hardly ever talked except to complain about the shitty jumpsuits they made us wear. They weren’t the worst things I’d ever owned, but Lucinda seemed to take having to wear one personally in a way I found particularly interesting.

Sunday Taylor was another one I thought I’d get along with, but she kept to herself and acted like she was the only good kid in a pack of misfits. Not like she was too good for us, but kind of like she was afraid if she got too close, the real Sunday would come out, and I’m pretty sure there’s a hell-raiser somewhere inside that meek exterior.

The last two members of our homemade clusterfuck were Cody Hewitt and Georgia Valentine. I figured Georgia for another rich white girl, but she’s the type who thinks she’s progressive ’cause she likes that one Beyoncé song and has a gay best friend. She can be kind of type A, but she’s always the first to take the jobs no one else wants to do and never talks shit about anyone.

Cody wasn’t Georgia’s gay best friend, but he was probably someone’s. That boy knows more about old movies than anyone I ever met. Of all of us out there, he seemed to belong the least. I couldn’t picture him doing anything worth getting sent to a shit hole camp for fuckups, but he was there, so he must’ve done something.

I don’t want to say anything about me. I don’t think the storyteller should get in the way of the stories, you know? But if you need a name, you can call me Gio.

* * *

Doug had taught us how to use a compass but hadn’t actually given us one when he dropped us off. All we got were our packs, sleeping bags, empty canteens, little bottles of bleach to disinfect the water with, and the clothes on our backs. Jaila figured out which direction to hike to get back to the Bend, but it was David who suggested that we should find water first. He wasn’t wrong. It didn’t get too hot in Wyoming in the summer, but it was warm enough that we were sweating, and once David mentioned water, none of us could think of anything else.

I brought up the idea of telling stories, saying it might help keep our minds off being thirsty, which was mostly true. Tino said it was a stupid idea, and he wasn’t interested in telling stories. The others didn’t seem real thrilled either. Not until I mentioned I’d give a hundred bucks to the person who told the best story as judged by me. But then no one wanted to be first, so we kept walking, hoping Jaila actually knew what she was talking about when she said to find water we should look for animal tracks and head downhill.

I figured my story idea was dead since no one was willing to be the sacrificial lamb, and I was thinking I could start shit between Tino and Sunday to keep me entertained, when Jenna, who’d been so quiet I’d almost forgotten she was there, was like “I’ll go first,” which surprised the hell out of me.

“THE BUTTERFLY EFFECT”

by Marieke Nijkamp

I WONDER IF FLAMES are fractals, too. The fire is hardly symmetrical, of course, but I could stare at the individual flames forever. They burn bright yellow and orange and red before succumbing to thick black smoke. They dance across the smoldering hood of the car. Given time, I could find patterns in them.

Or perhaps I would just find chaos. But chaos is enough.

I wrap my arms around my chest when sirens tear through the night. A few feet away, Adam holds Mom’s hand. Even though he stands her height these days, he looks young in his Transformers pajamas, frail in the fire’s glow. On the other side of the street, Dad is talking to Grandpa. Trying to calm him down, most likely, but it doesn’t seem to be working. He waves his hands and shouts something inaudible.

It’s weird. I always envisioned car fires to be violent and explosive, but perhaps that’s just Netflix and the movies. Grandpa’s car burns hot enough to warm the neighborhood and bright enough to light up the dark. It’s a steady roar.

I smile.

It’s almost calming to listen to.

* * *

I can hear you think: What is the matter with you, Jenna? Are you a pyromaniac? Let me put the record straight: Pyromania is an impulse control disorder, and I can control my impulses quite well, thank you very much. I’m not doing this for attention or to relieve tension or because the fire gives me gratification. It gives me satisfaction, sure, but that’s not quite the same thing. Car bad. Fire pretty.

No, it’s chaos. Fractals.

Fractures.

And I am fractured, too.

* * *

Broken. I first noticed it in precalc, of all places. My favorite class, bar none. What can I tell you? I’m a card-carrying nerd. And with a name like mine, there is no escaping the pull of math. After all, as my esteemed not-ancestor Georg Cantor once said, “The essence of mathematics lies entirely in its freedom.”

I wish I could tell him how much I long for that freedom, that entire essence.

Because it didn’t start in precalc. Of course it didn’t. It started long ago. But I always felt like I would mend the wounds and set the breaks and pretend like nothing was going on.

That day, today, for the first time, I can’t anymore. I can’t pretend class is normal and I’m normal. I’ve reached a breaking point. Perhaps I’ve already passed too many breaking points without noticing.

From the moment I settle into my spot in the back corner of the room, I try to focus on Mrs. Rodriguez’s lesson, but nothing that she says reaches me. Something about solving more complex equations than we’ve done so far, but she may as well have been speaking German. I’m not used to this. I coast through other classes, sure. I have everything I need: solid test scores, college plans, a middle-class suburban white family with money.

But with precalc, I want to care.

I doodle around the edges of my notebook; endless—familiar—geometrical shapes. The repetition is some kind of comfortable at least.

“Jenna.”

I blink and look next to me. Zoe is frowning at me, worry in her brown eyes. “Are you okay? I’ve whisper-called you five times at least.”

I don’t know what to say because just like with Mrs. Rodriguez’s explanations, Zoe’s words don’t quite reach me. And after a moment, her frown grows deeper. “Jenna, are you okay? Do you want to go see the nurse?”

In front of us, Kamal turns and glances at me too.

I force myself to grimace. “Sorry; tired. Must’ve had bad dreams or something.”

Though if I’m honest, I don’t remember the last time I slept long enough to have dreams at all. Sleeping means letting my guard down, and I’m exhausted down to my bones.

“Sucks.” Zoe reaches out to place a hand on my arm, and I flinch. I don’t want to. It’s Zoe. But I do.

“Just distract me, please? Maybe that’ll help.” Maybe Z. and I can still be normal even when everything else is shattering and slowly drifting out of reach.

“We’ll go to the Coffee House after school. Get you a mocha with extra whip and an extra shot of espresso and one of those lava muffins. There’s nothing extraordinary amounts of caffeine and sugar can’t fix.”

I roll my eyes, but my shoulders unclench a bit. Coffee with chocolate is Zoe’s answer to everything. She doesn’t need the caffeine; she has enough energy for the two of us—and most likely for half a dozen people more—even with swimming and volleyball. Her schedule is superhuman, and I don’t know how she manages it all when I can barely keep my studies going.

But coffee with chocolate is comfort. And I give her a small nod.

Z. flicks a strand of light brown hair out of her face

. “And in the interest of distraction . . .” She slides her notes over to my table. “Help me, please, oh math genius?”

I accept the piece of paper, but my stomach drops.

Math has always come naturally to me. I once told Dad it’s my second language—the universal language. He would much rather I learn German, but I’m fluent in formulas, and I think in theorems. I sleep, dream, breathe math.

I stare at the equation. I recognize Z.’s handwriting—entirely consistent, all small round letters and numbers—but I have no idea what she just put in front of me.

Next to me, Z. does that puppy-eyes thing she’s so good at. “I know you think cheating in math is a mortal sin, but I really don’t know. And Coach told me to do something about my grades, or she won’t include me in the starting lineup.”

She graces me with a smile, and her smile always makes my lips twitch up in return. Today I feel this shatter too. It hurts. Her happiness makes my blood boil. It’s not fair. I don’t want to lose this too. I don’t know what she’s asking of me, I don’t know how to give it to her, I don’t know how I let it get this far, I don’t know how to go on like nothing is wrong. This is the break.

I push the piece of paper back at her with too much force. It slides across her table and flutters to the floor.

“You should do your own work,” I snap, loud enough for the entire class to hear.

Everyone—and everything—around me falls silent. At the front of the class, Mrs. Rodriguez pauses midlecture and turns around.

And Zoe’s smile has melted off her face. She’s grown deadly pale. “Jenna . . .”

I drop my books into my bag and get to my feet, knocking over my chair. I don’t bother to pick it up. I don’t bother to mend this. I can’t.

“I’m done.”

* * *

Mom always said my temper was flammable, easily combustible. I get that from her. As a kid it was triggered by the simplest things—not getting what I wanted, a broken toy, my brother. But I thought I had it under control. It’s one more thing that’s unraveling.