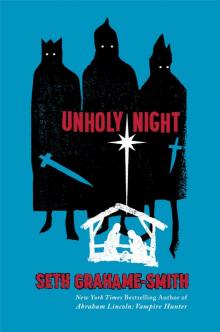

Unholy Night

Seth Grahame-Smith

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Copyright Page

For Gordon, who wouldn’t have believed a word of it.

“Do not be afraid. I bring you good news that will cause great joy for all the people. Today in the town of David a Savior has been born to you; he is the Messiah, the Lord. This will be a sign to you: You will find a baby wrapped in cloths and lying in a manger.”

—Luke 2:10–12

Go tell that long tongue liar,

Go and tell that midnight rider,

Tell the rambler, the gambler, the back biter,

Tell ’em that God’s gonna cut ’em down.

—Traditional Folk Song

2 BC

The magic of Old Testament times is coming to an end.

Great floods, mystical beasts, and parting seas have given way to the empires of man. Many believe that God has abandoned the world—most of which is ruled by Rome and its new emperor, Augustus Caesar.

One of many Roman provinces, Judea (in modern Israel), is ruled by a cruel puppet king named Herod the Great, who—although sickly and dying—fiercely clings to power through murder and intimidation. And he has reason to be paranoid, for the Old Prophecies tell of the imminent birth of a messiah—a King of the Jews—who will topple all the other kingdoms of the world…

1

Last Stand of the Antioch Ghost

“No king is saved by the size of his army; no warrior escapes by his great strength.”

—Psalm 33:16

I

A herd of ibex grazed on a cliff high above the Judean Desert—each of their tiny, antelope-like bodies dwarfed by a pair of giant, curved horns. A welcome breeze blew across their backs as they searched for what little shrubbery there was here in the great big nothing, each of them pushing their hot, cracked noses across the hot, cracked earth, gnawing at whatever succulent bits of green had managed to push their way through.

One ibex—tempted by the sight of a few lonely blades of grass on the cliff’s edge—grazed apart from the others, closer to the bone-shattering drop than even they dared go. These blades it now pulled at oh so carefully with its teeth. Its cloven hooves clacked against the loose rocks of its perch as it shifted its weight, sending the occasional pebble tumbling hundreds of feet into the valley below. Ten million years of geological aspirations undone in seconds.

Miles to the north of where it chewed this hard-earned meal, a carpenter was making his way toward Jerusalem in the blistering heat of midday—his head swimming through stories of plagues and floods to keep the thirst from driving him mad, his young, very pregnant wife asleep on the donkey behind him. And though the ibex would never know this—though its life, like the lives of all ibexes, would go completely unnoticed and unappreciated in the annals of history—it was about to become the sole living witness to a truly extraordinary sight.

Something’s wrong…

Perhaps it was a glint in the corner of its eye, a tiny, almost imperceptible vibration beneath its hooves. Whatever the reason, the ibex was suddenly compelled to lift its head and take in the sight of the vast desert below. There, off in the distance, it spotted a small cloud of dust moving steadily across the twisted beiges and browns. This in and of itself was hardly unusual. Dust clouds sprang up all the time, dancing randomly across the desert like swirling spirits. But two things made this cloud unique: one, it was moving in a perfectly straight line, from right to left. Two, it was being followed by a second, much larger cloud.

At least it looked that way. The ibex had no idea if clouds of dust could, in fact, chase each other. It only knew that they were to be avoided if at all possible, since they were murder on the eyes. Still chewing, it turned back to see if the others had spotted it. They hadn’t. They were all grazing away without a care in the world, noses to the ground. The ibex turned back and considered this strange phenomenon a moment longer. Then, convinced there was no danger to itself or the herd, it went back to its meal. The two clouds moved silently, steadily in the distance.

By the time it yanked another blade of grass out of the rock with its teeth, the ibex had forgotten they’d ever existed.

Balthazar couldn’t see a damned thing.

He rode his camel across the desert valley, kicking its sides like mad, his eyes the only things visible through the shemagh he wore to fight off the sun and the odor of the beast beneath him. Two overstuffed saddlebags hung off either side of his animal, and a saber hung from his belt, swinging wildly as they galloped along, kicking up the desert behind them. Balthazar turned back to see how close his pursuers were, but all he saw was the Cloud. The same, massive, relentless cloud that had been chasing him since Tel Arad. The cloud that made it impossible to tell how many men were after him. Dozens? Hundreds? There was no way to know. It was, at present, a cloud of undetermined wrath.

From the direction of that cloud there came a faint whistling, almost like the movement of wind through a ravine. At first it was just a single note, its pitch bending steadily lower and growing louder with each second. This note was joined by another and another, until the air behind Balthazar’s head was a chorus of faint whistles—each of them starting soprano and tilting tenor as they grew louder, closer. Just as Balthazar realized what they were, the arrows began to strike the earth behind him.

They’re shooting from horseback, he thought.

None of the arrows had come close enough to cause concern. Balthazar wasn’t surprised. Any experienced archer knew that firing an arrow from a galloping horse was akin to saying a prayer with a bow. Even at twenty yards, you had little chance of hitting your target. From this distance, it was hopeless—a sign of either desperation or anger. Balthazar didn’t think the Judeans were desperate. They were furious, and they were going to take that fury out on his skull if they caught up to him. After all, the untold legions in that cloud weren’t just chasing the thief who’d made off with a fortune of stolen goods, and they weren’t after the murderer who’d killed a handful of their comrades…

They were trying to catch “the Antioch Ghost.”

It was a nickname born of the only two things the Romans knew about him: one, that he was Syrian by birth, in which case it was a good bet that he’d grown up in Antioch; and two, that he had a knack for slipping into the homes of the wealthy and making off with their riches without being seen or heard. Other than those scant facts and a rough physical description, the Romans had nothing—not his age, not even his real name. And while “the Antioch Ghost” wasn’t particularly inspired as nicknames went, it wasn’t all that bad, either. Balthazar had to admit, he enjoyed seeing it among the “known criminals” painted on the side of public buildings—always in red, always in Latin: Reward! The Antioch Ghost—Enemy of Rome! Thief of the Eastern Empire! Sure, he hadn’t achieved the infamy of a Hannibal or a Spartacus, but he was something of a minor celebrity in his little corner of the world.

There was a second chorus of whistling, followed by a second strike of arrows behind him. Balthazar turned and watched the last of them fall. While still too far away to cause concern, this volley hadn’t been quite as hopeless as the last. They’re getting closer, he thought.

“Faster, stupid!” he yelled at the stubborn beast, kicking its sides with his heels.

If only he could get out of their sight for a minute or two, change direction. Even now, with an indeterminate number of Judean soldiers chasing him through the middle of nowhere, with only a tired, pungent camel and a dull sword to protect him, and even though his pursuers were only two minutes behind him at best, Balthazar still had a chance. He’d spent years memorizing a network of caves to hide out in, shortcuts across barren lands, the best places to scrounge up food and water on the run. He’d trained himself how to su

rvive. How to carry on in times when the whole world seemed hell-bent on snuffing him out. Times like now.

He sensed his camel slowing down and gave it another swift kick in its side.

C’mon…just a little longer…

The beast had struggled to keep pace with the weight of all that treasure on its back, and Balthazar had been forced to toss some of his heavier spoils overboard as they’d fled Tel Arad. The sight of all that wealth skipping across the sand had nearly made him sick to his stomach. The thought of some lucky shepherd stumbling upon his spoils made his jaw clench and his teeth grind. There was nothing more enraging, more unjust than denying a man the hard-earned fruits of his labor, especially when those fruits were made of solid gold. Balthazar had briefly considered cutting off one of his own limbs to shed an equal amount of weight. But the long-term prospects of a one-armed marauder were limited.

“Faster!” he cried again, as if this would spur on the camel any more than the thousand sharp kicks he’d delivered to its sides. It was still losing steam, and once again, Balthazar was forced to consider the unthinkable: jettisoning more of his hard-earned treasure.

He reached into one of the large saddlebags and fished around until his hands found something that felt heavy. He almost couldn’t bear to look as he pulled it out into the sunlight. There, in his hand, was a solid silver drinking cup—nearly the size of a bowl. Intricately carved and adorned with precious stones. It was a stunning piece, made from the finest materials with the finest artistry. It was also incredibly heavy. Balthazar held the chalice out to his side. Then, with his eyes averted and his stomach churning, he let it slip from his fingers. He turned away to spare himself the sight of it rolling across the desert floor and gave the camel another swift kick in retaliation.

C’mon, stupid…just a little longer…

It couldn’t be thirsty. A camel could drink forty gallons in one go, and its body could cling to that water for weeks. Its piss came out as a thick syrup of pure waste. Its shit was dry enough to use as firewood, for the love of God. No…it wasn’t thirsty. Not a chance. Tired? Unlikely. Camels had been known to live fifty years or more. And while Balthazar had gotten only a brief look at the face of this particular beast in the process of stealing it from a very unhappy Bedouin, he guessed that it was no more than fifteen years old. Twenty, tops. Still in the prime of its wretched life.

Just a little longer, you son of a bitch…

No, this camel was just being stubborn. And stubbornness could be corrected with a firm kick or two. Balthazar reckoned the beast could flat-out gallop for another hour. Maybe two. And if that estimate held up—if this camel could be coaxed through its stubbornness—then he had a real shot at making Jerusalem. And if he made Jerusalem, he was home free. There, he’d be able to blend in with the masses that were no doubt choking the streets for the census. He’d be able to disappear. Trade his stolen goods for coins, clothes, food—certainly a new camel.

Balthazar may have been a thief, but he deplored risk. Risk got men killed. Risk was unnecessary. When a man was prepared, when he was in control, things usually went according to plan. But the minute he left something to chance? The minute he trusted in partners, or instinct, or luck? That’s when everything went to hell. That’s why he was being chased across the desert by a giant cloud atop a stinking, unmotivated beast. Because he’d taken a risk. Because he’d committed the unforgivable sin of trusting his instincts.

As much as it irked him, as much as it went against everything in his nature, Balthazar had to accept that the outcome of his current predicament was beyond his control. He could kick and curse all he wanted…

It was up to the camel now.

II

It had all seemed so perfect. All the enticements had been there: a loosely guarded stash of expensive items, a corrupt nobleman, a populace being taken advantage of by the Romans. A more direct route to Balthazar’s heart couldn’t have been charted by a mapmaker.

Location had been another enticement. The city of Tel Arad was more than fifty miles south of Jerusalem. And the farther you were from Jerusalem, the less likely you were to encounter troops, whether they were King Herod’s Judean troops or Rome’s elite soldiers. And while Tel Arad still paled in comparison to Judea’s great city, it was home to a new, impressive temple of its own. To the noncriminal, that may have seemed like a trivial detail. But to Balthazar, it was everything. Temples meant travelers and money changers. They meant that a man with a strange appearance or accent was less likely to draw attention and that someone looking to trade stolen goods for gold and silver coins could do so with ease. Temples were a thief’s best friend.

Tel Arad had been settled thousands of years earlier, destroyed and rebuilt more times than any of the locals cared to remember. And for thousands of years, it had never grown beyond the rank of “desolate village.” But times had changed. Empires had sprung up on either side of the once-forgotten settlement and transformed it into a thriving center of trade. Suddenly Ted Arad was the central point between Roman goods heading east and Arabian goods heading west toward Egypt, the Mediterranean, and, ultimately, Rome—and its status had been steadily upgraded to “small city.”

The strongest sign of its growing importance had come only a year earlier, when Rome had decided to dispatch a governor—Decimus Petronius Verres—to look after the little city. Officially, Decimus was there to make sure Tel Arad adhered to the traditions and upheld the virtues of Roman life. Unofficially, and more importantly, he was there to put troublemakers to death and make sure the locals paid their taxes on time.

Decimus, for his part, had been crushed when he learned of the assignment. It had been presented as an “honor,” of course. He’d been “handpicked by Augustus himself to represent the empire in the East.” But Decimus knew what it really was: a castration. A punishment for taking sides against the emperor one too many times in the senate.

He’d privately sobbed when he’d heard the news. How could they do this to him? For one thing, the desert was no place for a Roman, especially one of his considerable weight and fair complexion. For another, he had been perfectly happy where he was: safely, quietly ensconced in the suburbs of Rome, surrounded by the trappings of reasonable, if not exorbitant wealth. He was in his fifties—far too old to be picking up his entire life and traipsing around in the heat. Rome was the center of the world. Home to all the entertainment and enticement a man could want. The desert, by contrast, was a death sentence. But the emperor had spoken. And castration or not, Decimus had no choice but to go.

Even the exiled members of Roman nobility weren’t expected to travel without the comforts of home. Shortly after his arrival in Tel Arad, Decimus ordered a walled compound built to his exact specifications—a scaled-up, fortified replica of the villa he owned in Rome. The same painter was brought in to re-create his favorite frescos, the same artisans to lay the mosaics on his floors tile by tile. The same formal garden and fountains dominated the courtyard at its center. The same slaves had made the journey to serve Decimus by day and the same concubines to serve him by night.

The finished compound was an impressive sight. A gleaming symbol of Roman superiority hidden from the public behind ten-foot walls. It sat atop a hill overlooking the northwest quarter of the little city, looking down on the temple and the bazaar below, where, as Decimus said, “the braying of animals, paying of merchants, and praying of men join together in a relentless chorus that deprives me of even a moment’s peace.”

But it wasn’t all bad in Tel Arad. It had taken some time, but Decimus had warmed to his new city. Not because of its cultural riches or natural beauty—it had neither. Not because of the local women—he’d imported his own. No, he’d taken a shine to his new home because it was, politely speaking, a garbage heap.

In Rome, there was always someone more powerful, someone who had to be placated or paid off. Things like treason and treachery bore very real, very severe consequences. Rome was a city of laws. But the desert wa

s lawless. In Tel Arad, Decimus was the only one who had to be placated. His pocket was the only one that needed to be lined. He was the law. It was a role he’d never had the opportunity to play in Rome, and it was one he found himself relishing more by the day.

As the governor of this godforsaken little sandpit, he had the power—indeed, the responsibility—to make sure the Arabian goods on their way to the West were up to “Roman standards,” a term that had a very loose and ever-changing definition but that could be more or less summed up as: “things Decimus didn’t feel like keeping for himself.”

He deputized a group of local men to serve as his “inspectors,” then turned them loose on the bazaar, where they conducted so-called quality checks at will. These inspectors targeted everything from jewelry to pottery to fabric to food. And if an item appeared to be of “lesser quality” or was “suspected of being a forgery”? It was confiscated and brought back to the governor’s compound for further inspection. There, Decimus had the final say on whether the item would be returned or whether it would be held indefinitely, in a room he’d specially built for the purpose. In the six months since the inspections had begun, not a single merchant could recall having an item returned. And if they complained? If they caused even the slightest trouble? Decimus made sure they never set foot in his bazaar again.

Now he was the one with the power to exile.

With that many stolen valuables stockpiled in one place, it hadn’t been long before Balthazar had caught wind of it. The rumors had reached him through the usual channels, and they’d been conveyed with the usual hyperbolic flair:

“Never has there been such a thieving Roman! He sits atop a pile of riches that would make the gods envious!”