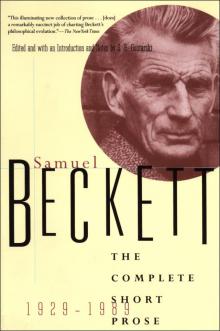

The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989

Samuel Beckett

The Complete Short Prose,

1929–1989

Works by Samuel Beckett published by Grove Press

COLLECTED POEMS IN ENGLISH AND FRENCH

THE COLLECTED SHORTER PLAYS

(All That Fall, Act Without Words I, Act Without Words II, Krapp’s Last Tape, Rough for Theatre I, Rough for Theatre II, Embers, Rough for Radio I, Rough for Radio II, Words and Music, Cascando, Play, Film, The Old Tune, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Breath, Not I, That Time, Footfalls, Ghost Trio, … but the clouds …. A Piece of Monologue, Rockaby, Ohio Impromptu, Quad, Catastrophe, Nacht and Träume, What Where)

THE COMPLETE SHORT PROSE: 1929–1989, edited by S. E. Gontarski (Assumption, Sedendo et Quiescendo, Text, A Case in a Thousand, First Love, The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, Texts for Nothing 1-13, From an Abandoned Work, The Image, All Strange Away, Imagination Dead Imagine, Enough, Ping, Lessness, The Lost Ones, Fizzles 1-8, Heard in the Dark 1, Heard in the Dark 2, One Evening, As the story was told, The Cliff, neither, Stirrings Still, Variations on a “Still” Point, Faux Départs, The Capital of the Ruins)

DISJECTA: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment

ENDGAME AND ACT WITHOUT WORDS

FIRST LOVE AND OTHER SHORTS

HAPPY DAYS

HOW IT IS

I CAN’T GO ON, I’LL GO ON:

A Samuel Beckett Reader

KRAPP’S LAST TAPE

(All That Fall, Embers, Act Without Words I, Act Without Words II)

MERCIER AND CAMIER

MOLLOY

MORE PRICKS THAN KICKS

(Dante and the Lobster, Fingal, Ding-Dong, A Wet Night, Love and Lethe, Walking Out, What a Misfortune, The Smeraldina’s Billet Doux, Yellow, Draff)

MURPHY

NOHOW ON

(Company, III Seen III Said, Worstward Ho)

THE SHORTER PLAYS: Theatrical Notebooks, Edited by S. E. Gontarski (Play, Come and Go, Eh Joe, Footfalls, That Time, What Where, Not I)

PROUST

STORIES AND TEXTS FOR NOTHING

(The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, Texts for Nothing 1–13)

THREE NOVELS

(Molloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable)

WAITING FOR GODOT

WATT

HAPPY DAYS: Production Notebooks

WAITING FOR GODOT: Theatrical Notebooks

WAITING FOR GODOT: A Bilingual Edition

GROVE CENTENARY EDITIONS

Volume I: Novels (Murphy, Watt, Mercier and Camier)

Volume II: Novels (Molloy, Malone Dies, The

Unnamable, How It Is)

Volume III: Dramatic Works

Volume IV: Poems, Short Fiction, Criticism

The Complete Short Prose, 1929–1989

Samuel Beckett

Edited and with an Introduction and Notes by S. E. Gontarski

Copyright © 1995 by the Estate of Samuel Beckett

Introduction copyright © 1995 by S. E. Gontarski

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected].

First Love originally written in French (1945): Premier amour © Les Editions de Minuit 1970; Stories and Texts for Nothing (The Expelled, The Calmative, The End, and Texts for Nothing I–XIII) originally written in French: (1945–1950) Nouvelles et Textes pour rien (L’Expulsé, Le Calmant, La Fin et Textes pour rien I-XIII) © Les Editions de Minuit 1955; The Image originally written in French (1958): L’Image © Les Editions de Minuit 1988; Enough originally written in French (1965): Assez © Les Éditions de Minuit 1966; Imagination Dead Imagine originally written in French (1965): Imagination morte imaginez © Les Editions de Minuit 1965; Ping originally written in French (1965): Bing © Les Éditions de Minuit 1966; Lessness originally written in French (1968): Sans © Les Éditions de Minuit 1969; The Lost Ones originally written in French (1969): Le dépeupleur © Les Editions de Minuit 1970; For to End Yet Again originally written in French (1975): Pour finir encore in Pour finir encore et autres foirades © Les Éditions de Minuit 1976; Fizzles 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 originally written in French (1972-1975): Foirades in Pour finir encore et autres foirades © Les Éditions de Minuit 1976; The Cliff originally written in French (1975): La falaise © Les Éditions de Minuit 1991.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beckett, Samuel, 1906-1989

[Prose works]

Samuel Beckett, the complete short prose, 1929-1989 / edited and with an introduction and notes by S. E. Gontarski.

Includes bibliographical references.

I. Gontarski, S. E. II. Title

PR6003.E282A6 1995 848′.91409—dc20 95-13074

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9843-3

Design by Laura Hammond Hough

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

Contents

Introduction

From Unabandoned Works: Samuel Beckett’s Short Prose

Assumption (1929)

Sedendo et Quiescendo (1932)

Text (1932)

A Case in a Thousand (1934)

First Love (1946)

Stories (from Stories and Texts for Nothing, 1955)

The Expelled (1946)

The Calmative (1946)

The End (1946)

Texts for Nothing (1—13) (1950—52)

From an Abandoned Work (1954—55)

The Image (1956)

All Strange Away (1963—64)

Imagination Dead Imagine (1965)

Enough (1965)

Ping (1966)

Lessness (1969)

The Lost Ones (1966, 1970)

Fizzles (1973—75)

Fizzle 1: [He is barehead]

Fizzle 2: [Horn came always]

Fizzle 3: Afar a bird

Fizzle 4: [I gave up before birth]

Fizzle 5: [Closed place]

Fizzle 6: [Old earth]

Fizzle 7: Still

Fizzle 8: For to end yet again

Heard in the Dark 1

Heard in the Dark 2

One Evening

As the story was told (1973)

The Cliff (1975)

neither (1976)

Stirrings Still (1988)

Appendix I: Variations on a “Still” Point

Sounds (1973)

Still 3 (1973)

Appendix II: Faux Départs(1965)

Appendix III: Nonfiction

The Capital of the Ruins (1946)

Notes on the Texts

Bibliography of Short Prose in English

Illustrated Editions of Short Prose

Introduction

From Unabandoned Works: Samuel Beckett’s Short Prose

WHILE SHORT FICTION was a major creative outlet for Samuel Beckett, it has heretof

ore attracted only a minor readership. Such neglect is difficult to account for, given that Beckett wrote short fiction for the entirety of his creative life and his literary achievement and innovation are as apparent in the short works as in his more famous novels and plays, if succinctly so. Christopher Ricks, for one, has suggested that the 1946 short story “The End” is “the best possible introduction to Beckett’s fiction,”1 and writing in the Irish Times (11 March 1995), literary editor John Banville has called “First Love” “the most nearly perfect short story ever written.” Yet few anthologists of short fiction, and in particular of the Irish short story, include Beckett’s work. Beckett’s stories have instead often been treated as anomalous or aberrant, a species so alien to the tradition of short fiction that critics are still struggling to assess not only what they mean—if indeed they “mean” at all—but what they are: stories or novels, prose or poetry, rejected fragments or completed tales. William Trevor has justified his exclusion of Beckett from The Oxford Book of Irish Short Stories (1989) by asserting that, like his countrymen Shaw and O’Casey, Beckett “conveyed [his] ideas more skillfully in another medium” (p. xvi). But to see Beckett as fundamentally a dramatist who wrote some narratives is seriously to distort his literary achievement. Beckett himself considered his prose fiction “the important writing.”2 The omission is all the more curious given that Beckett’s short pieces exemplify Trevor’s characterization of the genre as “the distillation of an essence.” Beckett distilled essences for some sixty years, and through that process novels were often reduced to stories, stories pared to fragments, first abandoned then unabandoned and “completed” through the act of publication. When that master of the Irish short story Frank O’Connor noted that “there is something in the short story at its most characteristic[—]something we do not often find in the novel—an intense awareness of human loneliness,”3 he could have been writing directly about Beckett’s short prose. As Beckett periodically confronted first the difficulties then the impossibility of sustaining and shaping longer works, as his aesthetic preoccupations grew more contractive than expansive, short prose became his principal narrative form—the distillate of longer fiction as well as the testing ground for occasional longer works-—and the theme of “human loneliness” pervades it.

Beckett’s own creative roots, furthermore, were set deep in the tradition of Irish storytelling that Trevor valorizes, “the immediacy of the spoken word,” particularly that of the Irish seanchaí. Although selfconsciously experimental, self-referential, and often mannered, Beckett’s short fiction is never wholly divorced from the culturally pervasive traditions of Irish storytelling. Even when his subject is the absence of subject, the story the impossibility of stories, its form the disintegration of form, Beckett’s short prose can span the gulf between the more fabulist strains of Irish storytelling and the aestheticized experimental narratives of European modernism, of which Beckett was a late, if formative, part. Self-conscious and aesthetic as they often are, Beckett’s stories gain immeasurably from oral presentation, performance, and so they have attracted theater artists who, like Joseph Chaikin, have adapted the stories to the stage or who, like Billie Whitelaw and Barry McGovern, have simply read them in public performance.

Much of Beckett’s short prose inhabits the margins between prose and poetry, between narrative and drama, and finally between completion and incompletion. The short work “neither” has routinely been published with line breaks suggestive of poetry, but when British publisher John Calder was about to gather “neither” in the Collected Poems, Beckett resisted because he considered it a prose work, a short story. Calder relates the incident in a letter to the Times Literary Supplement (24—30 August 1990): He had “originally intended to put [“neither”] in the Collected Poems. We did not do so, because Beckett at the last moment said that it was not a poem and should not be there” (p. 895). The work is here printed for the first time corrected (q.v. “A Note on the Texts”) and without line breaks, the latter to reinforce the fact that at least Beckett considered “neither” a prose work.

“From an Abandoned Work,” furthermore, was initially published as a theater piece by the British publisher Faber and Faber after it was performed on the BBC Third Programme on 14 December 1957 by Patrick Magee. Although “From an Abandoned Work” is now generally anthologized with Beckett’s short fiction, Faber collected it among four theater works in Breath and Other Shorts (1971). That grouping, of course, punctuated its debut as a piece for performance.4 It might be argued, then, that “From an Abandoned Work” could as well be anthologized with Beckett’s theater writings. It is no less “dramatic,” after all, than “A Piece of Monologue,” with which it shares a titular admission of fragmentation. Even as Beckett expanded the boundaries of short fiction, often by contracting the form, his stories retained that oral, performative quality of their Irish roots. Many an actor has discovered that even Beckett’s most intractable fictions, like Texts for Nothing, Enough, or Stirrings Still, share ground with theater and so maintain an immediacy in performance that makes them accessible to a broad audience.

With the exception, then, of More Pricks Than Kicks, which with its single, unifying character, Belacqua Shuah, is as much a novel as a collection of stories,5 and the 1933 coda to that collection, “Echo’s Bones,” which Beckett wrote as the novel’s tailpiece but which was rejected first by the publisher, Chatto and Windus, then by Beckett himself for subsequent editions, and most recently by the Beckett Estate for this collection, this anthology gathers the entire output of Beckett’s short fiction from his first published story, “Assumption,” which appeared in transition magazine in 1929 when he was twenty-three years old, to his last, which were produced nearly sixty years later, shortly before his death. In failing health and stirring little from his Paris flat, Beckett demonstrated that there were creative stirrings still, the title he gave three related short tales dedicated to his friend and longtime American publisher, Barney Rosset. In between, Beckett used short fiction to rescue what was in 1932 a failed and abandoned novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women, salvaging two discrete segments of that unfinished and only recently published (1992) work as short fiction, adding eight fresh, if fairly conventional, tales (or chapters) to fill out More Pricks Than Kicks (1934), a work whose title alone, although biblical in origin, ensured its scandalous reception and eventual banning in Ireland. In 1945—46 Beckett turned to short fiction to launch “the French venture,” producing four nouvelles: “Premier Amour” (“First Love”), “L’Expulsé” (“The Expelled”), “Le Calmant” (“The Calmative”), and “La Fin” or “Suite” (“The End”). These stories, “the very first writing in French,”6 seemed to have tapped a creative reservoir, for a burst of writing followed: two full-length plays, Eleuthéria and En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot), and a “trilogy” of novels, Molloy, Malone meurt (Malone Dies), L’Innommable (The Unnamable). When the frenetic creativity of that period began to flag, Beckett turned afresh to short fiction in his struggle to “go on,” producing thirteen brief tales grouped under a title adapted from the phrase conductors use for that ghost measure which sets the orchestra’s tempo. The conductor calls his silent gesture a “measure for nothing”; Beckett called his prose stutterings Texts for Nothing. For Beckett these tales “express the failure to implement the last words of L’Innommable: ‘il faut continuer, je vais continuer’”7 [“I can’t go on, I’ll go on”].

By the 1940s Beckett had apparently abandoned the literary use of his native tongue. Writing to George Reavey about “a book of short stories,” Beckett noted on 15 December 1946, “I do not think I shall write very much in English in the future.”8 But early in 1954 Beckett’s American publisher, Barney Rosset, suggested that he return to English: “I have been wondering if you would not get almost the freshness of turning to doing something in English which you must have gotten when you first seriously took to writing in French.”9 Shortly thereafter, Beckett began a new English novel, which he fir

st abandoned then published in 1958 as “From an Abandoned Work.” In a transcription of the story, a fair copy made as a gift for a friend, Beckett appended a note on its provenance: “This text was written 1954 or 1955. It was the first text written directly in English since Watt (1945).”10 Almost a decade intervened between “From an Abandoned Work” and Beckett’s next major impasse, a novel tentatively entitled Fancy Dying, portions of which, in French and English (with German translations of both), were published as “Faux Départs” to launch a new German literary journal, Karsbuch in 1965.11 That abandoned novel (q.v. Appendix II) developed into All Strange Away (where although “Fancy is her only hope,” “Fancy dead”) and its sibling, Imagination Dead Imagine, but was the impetus for several other Residua as well. Although these works were apparently distillations of a longer work, Beckett’s British publisher treated the 1,500-word Imagination Dead Imagine as a completed novel, issuing it separately in 1965 with the following gloss: “The present work was conceived as a novel, and in spite of its brevity, remains a novel, a work of fiction from which the author has removed all but the essentials, having first imagined them and created them. It is possibly the shortest novel ever published.”

In between Beckett completed an impressive array of theater work, including Fin de partie (Endgame) (1957), Krapp’s Last Tape (1958), Happy Days (1961), and Play (1964), and another extended prose work, Comment c’est (How It Is), itself first abandoned, then “unabandoned” in 1960. A fragment was published separately as “L’Image” in the journal X in December 1959. The English version, “The Image,” is here published for the first time in a new translation by Edith Fournier (q.v. “Notes on the Texts”). Another segment of How It Is was published as “From an Unabandoned Work” in Evergreen Review in 1960.12 For the next three decades, the post—How It Is period, Beckett would write, in French and English, denuded tales in the manner of All Strange Away, stories that focused on a single, often static image “ill seen” and consequently “ill said,” Residua that resulted from the continued impossibility of long fiction. As the titles of two of Beckett’s late stories suggest, these are tales “Heard in the Dark,” stories that were themselves early versions of the novel Company. And in a note accompanying the French manuscript of “Bing,” translated into English first as “Pfft” but quickly revised to the equally onomatopoetic “Ping,” Beckett noted: “‘Bing’ may be regarded as the result or miniaturization of ‘Le Dépeupleur’ abandoned because of its intractable complexities.” Abandoned in 1966, Le Dépeupleur was also unabandoned, “completed” in 1970, and translated as The Lost Ones in 1971. Throughout this period Beckett managed to turn apparent limitations, impasses, rejections into aesthetic triumphs. Adapting the aesthetics of two architects, Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more” and Adolf Loos’s “ornament is a crime,” Beckett set out to expunge “ornament,” to write “less,” to remove “all but the essentials” from his art, to distill his essences and so develop his own astringent, desiccated, monochromatic minimalism, miniaturizations, the “minima” he alluded to in the “fizzle” called “He is barehead.” As Beckett’s fiction developed from the pronominal unity of the four nouvelles through the disembodied voices of the Texts for Nothing toward the voiceless bodies of All Strange Away and its evolutionary descendant Imagination Dead Imagine, he continued his onto-logical exploration of being in narrative and finally being as narrative, producing in the body of the text the text as body. If the Texts for Nothing suggest the dispersal of character and the subsequent writing beyond the body, All Strange Away signaled a refiguration, the body’s return, its textualization, the body as voiceless, static object, or the object of text, unnamed except for a series of geometric signifiers, being as mathematical formulae. The subject of these late tales is less the secret recesses of the repressed subconscious or the imagination valorized by Romantic poets and painters than the dispersed, post-Freudian ego, voice as alien other. As the narrator of “Fizzle 2,” “Horn came always,” suggests, “It is in the outer space, not to be confused with the other [inner space or the Other?], that such images develop.”