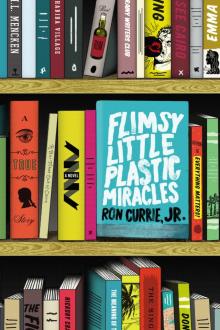

Flimsy Little Plastic Miracles

Ron Currie Jr.

Also by Ron Currie, Jr.

Everything Matters!

God Is Dead

Flimsy

Little

Plastic

Miracles

A True* Story

Ron Currie, Jr.

Viking

*For a sense of the way I hope the word “true” to be understood here, take a moment to consider the phrase “based on real events.” Specifically, consider the level and quality of your interest when reading something “based on real events,” and contrast that with how you feel reading something that purports to be entirely fictional.

And then please consider how every piece of art ever created is, to a greater or lesser degree, “based on real events.”

I’d even venture to suggest that your life, or at least the narrative you have of it in your head, is “based on real events,” rather than objectively true.

In any case, if you, like me, get goose bumps whenever you encounter those magic words, I encourage you to keep turning pages, because I promise, on my father’s grave, that that is exactly the sort of story you’ll find in this book.

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa), Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North 2193, South Africa • Penguin China, B7 Jiaming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2013 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © Ron Currie, Jr., 2013

All rights reserved

Publisher’s Note

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Currie, Ron, 1975–

Flimsy little plastic miracles : a true story / Ron Currie, Jr.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-101-60605-6

1. Man-woman relationships—Fiction. 2. Writers—Fiction. 3. Missing persons—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3603.U774F55 2013

813'.6—dc23 2012028931

Designed by Carla Bolte

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Contents

Also by Ron Currie, Jr.

Title Page

Copyright

Page Where An Epigraph Would Be Found

Flimsy Little Plastic Miracles

This is the page upon which an epigraph or two would be found, if I decided to use them. Personally, I have an ambivalent relationship with epigraphs. Though I understand that the ostensible point of an epigraph is to complement the book that follows, to illuminate its themes in some way or else lash it to the canon, too often the actual function of an epigraph seems to be to provide the author an opportunity to be pompous. To indulge in a little high-lit posturing. Because let’s face it, I’m no Nabokov, and if I were to swipe a line from Nabokov to use here, as I’d originally intended, wouldn’t I be placing myself next to him in some way, inviting you to think of us in the same context? And also, besides that, trying to give the impression that I read a lot of heavy deep smart esoteric shit, e.g. Seneca, whom I also considered including here? Trying to give the impression that I am, by association, heavy, deep, and smart myself? But here’s the thing: I haven’t read Seneca. I found a quote of his online, more or less by accident, and I cut-and-pasted it onto my original epigraphs page, and that somewhat disingenuous act was the thing that got me thinking about all this in the first place. I am much more intimately acquainted with the oeuvre of Rocky Balboa than that of Seneca.

It occurs to me, now, that they’re both Italian. So that’s something, I suppose.

The whole enterprise sort of stinks, epigraphs, is what I’m saying. But even now I’m still trying to impress, you understand. Trying to demonstrate my cleverness and authenticity by pointing out at length how epigraphs are often pretentious bullshit. Trying to disavow my intellectual vanity while simultaneously giving it a nice, long stroke. I’ve got other thoughts on this, thoughts involving contemporary advertising, among other things, and how it’s a sort of winking anti-advertising aimed at a demographic (namely, mine) weary and jaded from a lifetime of relentless sales pitches. But I can’t really carry this off, I’ve decided. It’s devolving into a possibly juvenile metafictional stunt that I’m likely to be made fun of for. And now I’m ending sentences with prepositions. For God’s sake, I don’t even know how to pronounce “oeuvre.”

Fuck it, here you go:

“Women weaken legs.”

—Mickey Goldmill, Rocky

It’s important that you understand, from the very outset, here, that everything I’m about to tell you is capital-T True. Or at least that I will not deliberately engage in any lies, of either substance or omission, in talking with you here today.

That you understand, in other words, how I’ve learned my lesson when it comes to trafficking in anything other than the absolute facts. And though I still don’t believe that the absolute facts are of primary importance, at least when trying to convey how something feels as opposed to simply how something happened, the lesson I’ve learned has been enormous and painful enough that I now have a sort of reflexive fear, almost a phobia, really, of allowing anything but the facts to escape my lips. So rest assured: if you sit there long enough to hear the whole story, there will be no embellishment or revisionism, and I will make no effort to appear any better, or indeed worse, than I actually was in all of this.

The first thing you need to know is that I am a writer. Or at least, I was a writer. I haven’t written a word since the book that you’d most likely know me for, the book that made me famous posthumously, and yet more famous post-posthumously.

I quit writing for one reason, then stayed quit for another.

The first reason was I killed myself, which obviously makes it tough to go on writing.

The second reason was I decided, after being exhumed, to never again speak anything but the facts, a resolution wholly incompatible with being a novelist.

The next thing you need to know is that I was once a skilled and successful seducer of women.

This is not braggadocio. Remember what I said a minute ago: I will not lie to you. It is simply true. I’ve always loved women, and been good with them. I grew up with three sisters, overheard countless conversations, listened to th

e music they listened to, studied the objects they coveted, even pondered their eating habits. I was the only straight teenage boy in the history of the world who read Forever cover to cover. I absorbed an ineffable understanding of women’s rhythms, an understanding that I’m pretty sure can only be gleaned from exactly the sort of estrogen-rich environment I was reared in—you can’t achieve it through study, for sure, and you probably can’t achieve it through any means whatsoever after the age of, say, fifteen or so. At that point you have a well-defined biological agenda vis-à-vis women, and can no longer interact with them in a way that confers genuine understanding. In other words, if by that age you haven’t got it, you never will.

From my eldest sister Pamela I learned about female ambition, and why some women favor bangs, and about the quietly vicious rivalry that often takes root between mothers and daughters, like a shoot of crabgrass in an otherwise lush and unsullied garden.

From my younger sister Cat I learned all the clichés: that women are fickle, and navigate by emotion rather than reason, and worry about their bodies, and shop tirelessly, and say it’s up to you then complain about the choice you make, and are best surrounded by an obliging silence right before their periods.

From my youngest sister Molly I learned the opposite of everything I learned from Cat.

So yes, I understood women. All the women who came into my orbit, save one.

This one woman I refer to. The one I loved but did not understand. The one who ended up arguably more famous than I am, as a consequence of that famous last book of mine that I never finished. The one who dismantled me not once but twice.

Yes, the thing about her is.

After she dismantled me the first time, I became a seducer of women, and I sought alternately to fuck her away and take gentle revenge on her, using every other member of her gender as proxy.

After the second dismantling, years later, I became the man sitting before you now.

I could try to explain to you the difference between those two men, but I’m more interested in what you see. Tell me, who am I now? Do my eyes shine? How is my posture, and what does it imply? What is the ratio of black hairs to gray on my head? In my beard? How do my gums look, and what does their appearance indicate regarding my overall health? I’m asking you sincerely, here. I have no idea myself.

Emma, is her name. Maybe you knew that. Emma, the object of my tireless, timeless, even-I’m-sick-to-death-of-it affection. Emma. A regular and common name. Attached to anyone else it carries no significance for me whatsoever. But some nights, even now, I find myself rolling those two syllables off my tongue as though they contain some great and wonderful secret, and then I feel silly, and rightly so, when the sound escapes from my mouth and dissipates.

One thing you can never understand, from reading the book or seeing the movie or even me sitting here telling you, is the scope of her beauty. Her loveliness, witnessed, exposes language for the woefully limited mode of communication that it is. Nevertheless, I am always compelled to try and explain: she’s objectively and undeniably beautiful. She’s self-possessed, successful, whip-smart, often an enigma, which of course I can’t resist. She laughs with her whole body, but you’ve got to work a little harder to make her laugh. And her eyes: clear, flinty orbs that reveal as much as they take in; more, perhaps. You’ll never learn who she is from anything that comes out of her mouth. It’s the eyes.

Not that any of that matters now. You know how all that worked out. At least, you know a version of it, the version I put into the book that made me famous—or, more likely, you’re familiar with the celluloid version that Hollywood birthed. Neither the book nor the movie is an accurate representation of what actually happened between me and Emma, but the salient point is that all three versions—film, book, and real life—end the same way: with the two of us very much apart.

Before the book that made me famous, I wrote an exceedingly obscure book that was, among other things, a love letter to Emma. This was my first novel, which basically got ignored on publication and, somewhat surprisingly, remained more or less ignored even after Emma’s book was published and I became famous. When my first novel came out, as far as I knew Emma was happily married. I didn’t write the book with any notion of her recognizing herself and swooning and leaving her husband when she realized that after all these years she actually wanted me. I wrote the book because I still loved her and needed to write about that.

Besides, she didn’t swoon and leave her husband. Her husband left her. It was pure coincidence that I published my first novel around the time that her marriage was coming apart.

The book wasn’t about her, strictly speaking—it was Hollywood high-concept and very busy, featured among other things a catastrophic comet strike on the Earth, shadowy government agencies and triple-amputee domestic terrorists, exhaustive ruminations on baseball and Catholicism and cocaine, et cetera. But the female lead in the book, the love interest, was based on Emma to a degree that made it obvious to anyone who knew her. And when she read the book herself, she started showing up more often, and calling, and emailing, and sending me photos of nice places she traveled to. Basically insinuating herself into my life again, after a very, very long time, the prospect of which both delighted and terrified me.

And also confused me, given that as far as I knew she was happily married.

But maybe it’s better to start in medias res. The storyteller in me seems to think so. He’s way in the back of the classroom, but he’s got his hand up and he’s waving it back and forth sort of frantically and squirming around in his seat. Like he really wants to be heard on this one, after going silent for so long. And he’s saying to me, Start in the middle. The beginning is really of interest only to you, buddy, is what he’s telling me.

This, despite the fact that the novel that made me famous, the novel based on the real-life factual experiences I’m about to break down for you with absolute honesty and forthrightness, begins at the beginning and set up camp on the Times best-seller list for longer than To Kill a Mockingbird.

Nonetheless, my inner storyteller has changed his mind. He wants to start where the action starts.

The action in question being my exile to the Caribbean island, that verdant hell, and the suicide attempt that followed shortly thereafter. Again, all well but falsely documented.

Here’s how it really happened.

One more thing, though, before I begin in earnest. I want to make sure we’re on the same page here, you and I. I want to make sure you understand that I am not rehashing news reports and online speculation for you as if you haven’t heard them already. Everyone thinks that because they read Emma’s book, they know what happened to bring me to that morning on the island when I tried and failed to kill myself. And everyone thinks that they know what happened when I became famous post-suicide, because my life was investigated and studied and reported on ad nauseam.

They don’t know, of course. Not all of it. Not nearly all of it. But if you sit there long enough, I’ll tell you all of it. The real story. The unvarnished, unsexy, meandering, directionless, embarrassing, capital-T Truth. The truth that everyone thought they wanted from me—the truth they sat on witness stands and television stages demanding—is what I offer you.

So how I ended up on the island was, I was with Emma on her bed, fucking her from behind, and she reached back and clawed my thigh, digging deep red rivulets that would take two weeks to heal, and I clenched my jaw against what was pretty considerable pain and fucked her harder, and suddenly she straightened up and pulled away and knelt with her face pressed against the wall over the headboard and her arms crossed over her breasts. She made terrible frightened childlike noises. She hugged herself and trembled as though she’d just woken up from a nightmare that wouldn’t recede. I moved closer to her, tentative, and when I placed my hands on her shoulders she f

linched, but then she let me hold her, and she continued to tremble and I asked What is it, honey, but she couldn’t tell me, and her eyes were wide and searched the room, the walls and the ceiling, as though she were suddenly struck blind.

Later that night she asked me to go away. To leave the country for a few months while her divorce was finalized and she got her professional life, which she’d neglected over the last year, back in order.

I can’t stay away from you if you’re nearby, she said. And I need to be away from you for a while, until this is done. Until I feel like I’m standing on my own, not using you to stay upright.

I didn’t want to leave her. I knew if I left she would disappear from me again. But I agreed.

And that was how I ended up renting a bright pink stucco house on the Caribbean island, sweating rum and banging on the keyboard and filling page upon page with thousands of words about Emma, while up north, on the mainland, where she was, snow fell day after day in great hoary piles, and municipalities took to suspending their environmental laws and dumping the stuff in whatever river was nearest by, damn the consequences to fish or aquatic flora or anyone unlucky enough to live downstream.

Of course, it wasn’t as though I just got on a plane the next afternoon. Several sober, reasoned, ostensibly dispassionate conversations followed the night when she panicked, during which we discussed all the very good and obvious reasons why we should take time apart. She’d be spending more of her workweeks in Washington; I usually departed for warmer climes in January and February anyway, so it just made sense. She still trailed her broken marriage like a rusty muffler dragging behind a car; I was under the water of a yearlong bender, so it just made sense. She worried she’d turn out a monster like her mother; I had a book to write, so it just made sense. She was being stalked by a mysterious figure who had burned down her house and may or may not have wanted her dead; I sometimes gave serious thought to flinging myself in front of trains and off of highway overpasses, so it just made sense. She didn’t trust herself but wanted me to trust her; my blood stagnated at the mere thought of her betraying me again, so it just made sense. Her mother was cruel and crazy; my father was dead, so it just made sense.