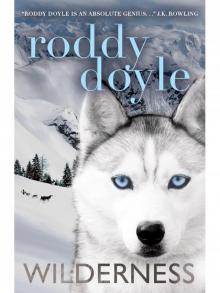

Wilderness

Roddy Doyle

Praise for Roddy Doyle’s children’s books

“The Booker prize winner’s work is not only admired but truly loved . . . his words reach across every barrier of age and gender”

Adèle Geras in The Scotsman

“Roddy Doyle is rude, silly, irreverent and infectiously funny”

East Anglian Daily Times

“Doyle’s narrative style is deceptively simple as he narrates this family adventure story. . . A leisurely read with convincing dialogue”

The Northern Echo

“THE ROVER ADVENTURES are packed full of bizarre humour, imagination and a whole lot of poo. . .”

Bookseller

“Riotously funny”

The Times

“Brilliant”

Irish Independent

Also by Roddy Doyle

A Greyhound of a Girl

The Giggler Treatment

Rover Saves Christmas

The Meanwhile Adventures

Her Mother’s Face

For Liz and Lucy

Contents

Cover

Praise

Also by Roddy Doyle

Title Page

Dedication

The Eyes

Chapter 1

The Bedroom

Chapter 2

The Bus

Chapter 3

The Airport

Chapter 4

The Airport

Chapter 5

The Taxi

Chapter 6

The Café

Chapter 7

The Bedroom

Chapter 8

The Kitchen

Chapter 9

The Kitchen

Chapter 10

The Kitchen

Chapter 11

The Door

Chapter 12

The Airport

Copyright

The Eyes

The two boys looked at the dog’s eyes.

“What colour are they?” said Johnny.

“Don’t know,” said Tom.

The eyes were like nothing the boys had ever seen before. There really was no name for their colour.

“Blue?” said Tom.

“No,” said Johnny.

“Turquoise?”

“Not really.”

The dog stared back at them. Most of the other dogs in the pen were howling and making noises that sounded quite like foreign words. They were rattling and stretching their chains. But this dog in front of them was different. He stood there in the dirty snow, as calm as anything, and looked at the boys, at Tom, and then at Johnny, at Tom, then Johnny.

They weren’t really like dog’s eyes at all. At least, they weren’t like the eyes of any of the dogs the boys knew at home. Lots of their friends had dogs, and their aunt had two of them, but all of those dogs had proper dog eyes. But this dog looking at them had eyes that seemed to belong to a different animal, maybe even a human.

“It’s like there’s someone trapped in there,” said Tom.

Johnny nodded. He knew exactly what his brother meant.

They stepped back, still looking at the dog. They were afraid to turn their backs on him. They stepped back again, into thick, clean snow. They did it again, and bumped into something hard. They turned, and looked up at the biggest, tallest, widest man they’d ever seen.

The man was a solid wall in front of them. The dog was right behind them.

“Why – are – you – here?” said the man.

CHAPTER ONE

Johnny Griffin was nearly twelve and his brother, Tom, was ten. They lived in Dublin, with their parents and their sister. They were two ordinary boys. And they were being very ordinary the day their mother made the announcement.

They were in the kitchen, doing their homework. It was raining outside, and the rain was hammering on the flat roof of the kitchen. So they didn’t hear their mother’s key in the front door and they didn’t hear her walking up the hall. Suddenly, she was there.

They always loved it when she came home from work, but this was even better, because she was soaking wet. There was already a pool at her feet.

“I’m a bit wet, lads,” she said.

She shook herself, and big drops of secondhand rain flew at the boys and made them shout and laugh. She grabbed them and pressed their faces into her soggy jacket. Tom laughed again, but Johnny didn’t. He thought he was too old for this.

“Let go!” he yelled into the jacket.

“Say please,” said his mother.

“No!” said Johnny.

But she let him go, and his brother too.

“There’ll be no rain where we’re going, lads,” she said.

That sounded interesting.

“Only snow.”

That sounded very interesting.

So she told them what she’d done that day, at lunchtime. She’d been walking past a travel shop and something bright in the window caught her eye. She stopped and looked. It was a hill in the window, made of artificial snow, and there was a teddy bear skiing down the hill. It was an ad for winter holidays.

“It was really stupid, lads,” she said. “The poor teddy was wearing a crash helmet that was way too big for him and his skis were on back to front. But, sure anyway, I went in and booked a holiday for us.”

“Where?” said Johnny.

“Finland.”

The boys went mad. Tom ran down the hall, up the stairs, jumped on the beds and came back.

“Where’s Finland?” he asked.

They got Johnny’s atlas out of his schoolbag and found Finland. Their mother showed them the route they’d be taking. Her finger went from Dublin, over the Irish Sea.

“We’ve to fly to Manchester first,” she said.

And her finger turned at Manchester, and headed north across the page.

“And then to Helsinki.”

They liked the sound of that place.

“Helsinki! Helsinki!”

They thumped each other and laughed.

“And then,” said their mother, “we change planes again and fly even further north.”

Her finger went up from Helsinki, and stopped.

“To a place that isn’t on the map,” she said.

“Why not?” said Tom.

“It’s probably too small,” said Johnny.

“That’s right,” said their mother.

“What’s it called?”

“I can’t remember,” said their mother. “And I left the brochure at work. But it looks lovely.”

“When are we going?” said Johnny.

“In two weeks,” she said.

“Deadly,” said Tom.

“But we’ll still be in school,” said Johnny.

He’d worked it out. It was the middle of November. Add two weeks and they’d be at the beginning of December, still three weeks before the Christmas holidays.

“No, you won’t,” said their mother. “I already phoned Ms Ford.”

Ms Ford was the principal of their school. Johnny was in sixth class, and Tom was in fifth.

“She said she was inclined to look favourably at my request, because it’ll be such an educational experience for both of you.”

“Does that mean we can go?” said Johnny.

“Yes,” said their mother. “She said fire away, but to be sure to bring her

home a present.”

So that was it. They were going to Finland.

“Coo-il!”

That much was true. But some of the things their mother had told Johnny and Tom weren’t true at all. She’d told them she’d left the brochure on her desk at work. But she hadn’t. It was in her bag. But she didn’t want them running off and rooting through her bag. There were things in there that she didn’t want the boys to see. She’d told them that the teddy in the window was wearing a helmet that was too big, and skis that were back to front. That wasn’t true. Because there was no teddy. And she’d told them she’d gone straight in and booked the holiday. But that wasn’t true either. She had booked the holiday at lunchtime that day. But she’d been thinking about doing it for weeks.

Johnny and Tom’s mother was called Sandra. Sandra Hammond.

“Is Dad going with us?” Tom asked later, when they were having their dinner.

Their father’s name was Frank. Frank Griffin.

“No,” said Sandra.

“Why not?”

“Well,” said Sandra. “It’s an adventure holiday. And you know your dad. His idea of an adventure is going to the front door to get the milk.”

“What about Gráinne?”

Gráinne was their sister.

“No,” said Sandra. “She won’t be coming either.”

“How come?” said Johnny.

“She wouldn’t want to,” said Sandra.

Tom and Johnny didn’t mind. Their mother was right. Gráinne wouldn’t want to go with them, even to as cool a place as Finland. Gráinne was much older than the boys. She was eighteen. And Tom and Johnny didn’t like her much. Mainly because she didn’t like them.

Their father came home. They heard the music. He always played it loud, with the car windows down, but only when he turned into the drive. He did it to annoy their neighbour. It was a long story. Or, at least, it went back a long time. It went way back, to when Gráinne was only three, and Frank was married to a woman called Rosemary, and they were moving into the house. Frank was helping the removal men carry a couch into the house. But he wasn’t being much help. Actually, he was in the way. He was standing at the door watching Gráinne. She was talking to a woman who was cutting her side of the hedge. This was Mrs Newman, their new neighbour, although she wasn’t new at all – she was at least forty. And Gráinne was talking to her.

“Hello,” she said.

But the new neighbour wasn’t talking back.

“Hello, lady,” said Gráinne.

Mrs Newman just kept chopping the hedge.

“Hello, lady,” said Gráinne.

Frank hopped over the couch and went straight over to the hedge.

“My daughter has been saying hello to you,” he said.

“What?” said Mrs Newman.

“She’s been saying hello to you,” said Frank.

“I didn’t hear her,” said Mrs Newman.

She didn’t really look at Frank. She leaned out and chopped a bit of hedge with the shears. It fell at Frank’s feet.

“I’m a bit deaf,” she said.

“Oh,” said Frank.

He put his hand out, over the hedge.

“I’m Frank Griffin, by the way.”

But Mrs Newman didn’t shake Frank’s hand. In fact, she nearly chopped his fingers off. He took his hand back just in time. He felt the breeze on his fingertips as the two blades snapped together.

He picked up Gráinne and carried her into their new house. He didn’t speak to Mrs Newman again, but he didn’t start playing the music loud until much later, about three years after they’d moved into the house. It was the sad part of the story. Frank and Rosemary weren’t happily married any more. He didn’t know why not, and neither did she. It just seemed to happen. They didn’t love each other any more. And they argued. About small things, about stupid things. They had a big argument about a rotten apple Frank found in the bottom of Gráinne’s schoolbag. The apple mush had seeped into two of her copy books, and he blamed Rosemary for it. He knew he was being mean. But he couldn’t help himself. That was what it felt like – he wanted to stop but he couldn’t.

“If you had any interest in her education you’d have found that apple before it exploded in her bag,” he said.

He was shouting.

“And what about you?” said Rosemary.

She was shouting back. They were in their bedroom, at the front of the house. It was a nice night, in September. The window was wide open. Frank saw it, the open window, and he didn’t care.

“Where’s your interest in her education?” said Rosemary.

“I’m more interested than you,” said Frank. “That’s for sure.”

The argument went on like that. It was really stupid and pointless.

The doorbell rang. Rosemary looked out the window and saw the police car.

“Oh, God,” she said.

They both went down to answer the door. The two Guards, a man and a woman, looked embarrassed and very young. There’d been a complaint about noise, they told Frank. The woman, the Bean Garda, did the talking. Rosemary was right behind Frank, looking at the Guards over his shoulder. Frank apologized, and Rosemary behind him nodded too. They were both very sorry.

“Yes, well,” said the Bean Garda.

She was looking carefully at both of them, Frank suddenly realized, and he wanted the floor to open up and swallow him. She was looking for bruises, or red skin, proof that they’d been violent.

“It was just a row,” said Frank. “Sorry.”

The Bean Garda had finished her examination.

“Well,” she said. “We all have them now and again. But maybe you could close the windows the next time, Mr Griffin.”

Frank laughed but, really, he’d never felt less like laughing in his life. He felt so humiliated and awful – he just wanted to shut the door. And that was what he was doing when he saw the cigarette. They both saw it. It was dark out there, especially when the police car turned and went. But there it was, the glowing cigarette, at the other side of the hedge. Mrs Newman was behind the cigarette, looking at them. And they knew. She was the one who’d phoned the Guards.

“She’s only deaf when it suits her,” said Frank as he shut the door.

Frank and Rosemary hugged each other in the hall. They went into the kitchen, made tea, and agreed that they couldn’t live together any more. It was a terrible night, and Frank always blamed Mrs Newman for it. He knew he wasn’t being fair. But when he thought about that night, and the days and months that led up to it, he always saw that glowing cigarette. Thirteen years after that night, eight years after Mrs Newman gave up smoking, Frank still played loud music when he drove into the drive, just to let her know. He knew – she wasn’t deaf at all. He wasn’t angry any more. But he still liked to annoy Mrs Newman.

Johnny and Tom met him at the front door.

“We’re going to Finland,” said Tom.

“Make sure you’re home in time for bed,” said Frank.

“In two weeks,” said Tom.

“Are you serious?” said Frank.

He took his jacket off and hung it on the bannister.

“Yeah,” said Johnny. “We’re going with Mam.”

“Come down to the kitchen and tell me all about it,” said Frank.

But he knew all about it already. It had actually been his idea. And the excitement on the boys’ faces was the best thing he’d seen in a long time.

The day after their last argument, Rosemary made Gráinne’s lunch for school. She helped Gráinne put on her coat, and then she walked with Gráinne down the road to the school. She kissed Gráinne, and hugged her.

“Bye-bye, honey-boo,” she said. “Have a lovely day.”

Then she stood at the school railings and watched Gráinne as she walked across the yard and in the door. She was crying and she didn’t care that people were looking at her. She walked home and packed two suitcases. Gráinne’s granny collected Gráinne from school, and Frank collected her from her granny’s house on his way home from work. Rosemary was gone when Frank and Gráinne got home.

“Where’s Mama?” said Gráinne.

“She’s gone on a holiday,” said Frank.

That was the question, and that was the answer for days after that, and then another question was added.

“When’s she coming home?”

And another answer.

“In a while.”

And another question.

“When?”

And the answer.

“I don’t know.”

Then Gráinne stopped asking the questions.

For a long time Frank heard nothing about Rosemary. He found out that she’d gone to America. Then he heard she was living in New York. She phoned her parents a few times a year, and sent her love to Gráinne. But that was all.

For a long while, it was just him and Gráinne. And it was fine. They were lonely, but they were lonely together. Gráinne missed her mother, and stopped believing that she’d ever come home. But she loved her father and he was always there, smiling, always downstairs when she was falling asleep, always awake before her. Always her father.

Then he met Sandra.

They met at a concert. She was there with her boyfriend, and she was sitting in Frank’s seat.

He looked again at his ticket.

“M17,” he said. “You’re in my seat, sorry.”