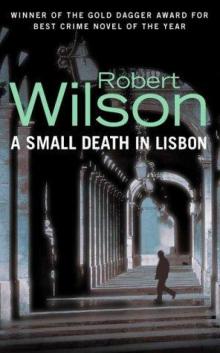

A Small Death in Lisbon

Robert Wilson

A Small Death in Lisbon

Robert Wilson

* * *

HARCOURT, INC.

New York San Diego London

* * *

Although this novel is based on historical fact the story itself is complete fiction.

All the characters and events are entirely fictitious and no resemblance is

intended to any event or to any real person, either living or dead.

Copyright © Robert Wilson 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,

recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be

mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.harcourt.com

First published in England by HarperCollins Publishers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Robert, 1957—

A small death in Lisbon/Robert Wilson—1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-15-100609-1

1. Police—Portugal—Lisbon—Fiction.

2. Lisbon (Portugal)—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6073.I474 S6 2000

823'.914—dc21 00-035042

Typeset in Janson Text

First U.S. edition

E G I K J H F

Printed in the United States of America

* * *

For Jane

and

my mother

* * *

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I'd like to thank Michael Biberstein for correcting my German and Ana Nobre de Gusmão for checking all things Portuguese. Any errors that remain are of my own making.

Over the years a lot of people have talked to me, and contributed with information, insight and books. I'd like particularly to thank the following: Mizette Nielsen, Paul Mollet, Alexandra Monteiro, Natalie Reynolds, Elwin Taylor and Nick Ricketts.

This book took some research and the staff of The Bodleian in Oxford, A Biblioteca/Museu 'República e Resistência', A Biblioteca de Estudos Olisiponenses and A Biblioteca Nacional in Lisbon, were always helpful.

I also visited the Beira and the following were particularly friendly and helpful: R. A. Naique, Director Geral of Beralt Tin & Wolfram, Fernando Pàolouro of the Journal do Fundào, José Lopes Nunes and Councillor Francisco Abreu of Penamacor. In addition I would like to thank the people of Fundào, Penamacor, Sabugeiro, Sortelha, and Barco for their help and memories. I would also like to thank Manuel Quintas and the staff of the Hotel Palácio in Estoril.

Finally, although this book is dedicated to her, that does not do justice to my wife's contribution to the work. She was tireless in discussing with me the form of the book, she put in days of research in Oxford and Lisbon, she gave me total support and encouragement through the long months of writing and she was a dedicated and intelligent editor. This would have been a doubly hard task without you. Thank you.

She was lying on a crust of pine needles, looking at the sun through the branches, beyond the splayed cones, through the nodding fronds. Yes, yes, yes. She was thinking of another time, another place when she'd had the smell of pine in her head, the sharpness of resin in her nostrils. There'd been sand underfoot and the sea somewhere over there, not far beyond the shell she'd held to her ear listening to the roar and thump of the waves. She was doing something she'd learned to do years ago. Forgetting. Wiping clean. Rewriting little paragraphs of personal history. Painting a different picture of the last half-hour, from the moment she'd turned and smiled to the question: 'Can you tell me how...?' It wasn't easy, this forgetting business. No sooner had she forgotten one thing, rewritten it in her own hand, than along came something else that needed reworking. All this leading to the one thing that she didn't like roaming loose around her head, that she was forgetting who she was. But this time, as soon as she'd thought the ugly thought, she knew that it was better for her to live in the present moment, to only move forward from the present in millimetre moments. 'The pine needles are fossilizing in the backs of my thighs,' was as far as she got in present moments. A light breeze reminded her that she'd lost her pants. Her breast hurt where it was trapped under her bra. A thought tugged at her. 'He'll come back. He's seen it in my face. He's seen it in my face that I know him.' And she did know him but she couldn't place him, couldn't name him. She rolled on to her side and smiled at what sounded like breakfast cereal receiving milk. She knelt and gripped the rough bark of the pine tree with the blunt ends of her fingers, the nails bitten to the quick, one with a thin line of drying blood. She brushed the pine needles out of her straight blonde hair and heard the steps, the heavy steps. Boots on frosted grass? No. Move yourself. She couldn't get the panic to move herself. She'd never been able to get the panic to move herself. A flash as fast as a yard of celluloid ripped through her head and she saw a little blonde girl sitting on the stairs, crying and peeing her pants because he'd chased her and she couldn't stand to be chased. The rush. The gust of terrible energy. The wind up the stairs, whistling under the door. The forces winding up to deliver. Doors banging far off in the house. The thud. The thud of a watermelon dropped on tiles. Split skin. Pink flesh. Her blonde hair reddened. The cranial crack opened up. The bark bit a corner of her forehead. Her big blue eye saw into the black canyon.

Part One

Chapter I

Friday, 12th June 199–, Paço de Arcos, near Lisbon

'Ladies and gentlemen,' said the mayor of Paço de Arcos, 'may I present to you Inspector José Afonso Coelho.'

It had been a hot day with a perfect blue sky and now a soft lick of a breeze was coming off the ocean to mess with the poplars and pepper trees in the public gardens. The faded pink disused cinema's walls drank in the evening light, a small girl squealed, rocking on a happy dinosaur, a big man smoked and sucked beer next to her, women greeted each other with kisses, their dresses rippled in the cool. Cars flashed past on the Marginal, a light aeroplane sputtered out to sea over the sand bank. The air was redolent of grilled sardines and a bureaucrat had a microphone.

'Zé Coelho,' said the mayor, using my more recognized name, but still not squeezing out much more interest from the festa de Santo António crowd which included my sixteen-year-old daughter, Olivia, my sister and brother-in-law and four of their seven children.

The mayor talked on, elaborately explaining the event in rococo Portuguese to a robustly inattentive public consisting mostly of my neighbours, who were well apprised of the bare facts which were: my wife died a year ago, I put on weight, to encourage me to take it off my daughter arranged this charity event with money pledged against each kilo lost and if I was a single gram over eighty kilos I was to have my perfect, neatly-clipped beard of twenty years shaved off in front of this rabble.

My daughter waved at me, my brother-in-law gave me a thumbs-up. I weighed in that morning at seventy-eight kilos, my stomach hadn't been as hard and flat since I was eighteen and I'd been cycling 250 kilometres a week with the police trainer. I was feeling supremely confident ... until the mayor had started talking. There was something mannered about the crowd's insouciance, something insincere about my brother-in-law's encouragement, even my daughter's wave. I had a part to play, I knew it at that moment.

A fat man, balding with a heavy moustache, wearing a blazer, grey slacks and a wild tie arrived at my daughter's table. He kissed her on both cheeks and squeezed her shoulder. One of my nieces made

room for him and after shaking everybody's hands he sat down.

There was a sudden silence. The mayor had arrived at the money. There was respect for the money.

'Two million, eight hundred and forty-three thousand, nine hundred and eighty escudos.'

The crowd went up like a flight of fantails. That ... even I had to agree, was a hell of a lot of money for seventeen kilos of lard. I held up my hand and took the applause like a returning monarch.

The band on the stand behind me cut in on my dignity and played a jaunty little number as if I was a toureiro who'd just executed a blinding move against the bull, and a group of small girls in traditional costume broke out into disorganized, elephantine dancing. Two local fishermen lifted a set of scales up on to the platform. The crowd left their seats by the bar and rushed the stage. The fat man sitting next to my daughter had his pen out and was writing. The mayor was fighting people off who wanted a go with the microphone which he'd stuffed inside his suit and the speakers were carrying the crunching explosions from his armpit.

Calm was restored by my doctor mounting the podium. He balanced a pince-nez on his nose and explained the rules like an oncologist who'd been asked to give a terrible prognosis without holding back on the details. He introduced my barber who'd crept up behind me with a cloak and scissors.

I stepped out of my shoes and on to the scales. The doctor adjusted the top scale to eighty and counted down from eighty-nine. The crowd joined in. I held my head up, gave them the full force of my brand-new bridgework, closed my eyes and thought:—soufflé, helium-filled soufflé.

At eighty-three I heard the crowd wavering. I was levitating like a Brahmin. At eighty-two, my eyes snapped open, the scales middled out and the doctor gravely announced major surgery. I was outraged. The crowd roared.

The two fishermen pressed me into a chair. I lashed out. The girls in national costume fled. Did I overdo that? I remonstrated and allowed myself to be pinioned. My barber stropped his razor and looked at me out of the half-closed lids of a casual killer. The mayor shouted his eyes clean out of his head until he remembered the microphone.

'Zé, Zé, Zé,' he said, bringing forward the fat, bald, moustachioed man who'd been sitting with my family, 'this is Senhor Miguel da Costa Rodrigues, Director of the Banco de Oceano e Rocha. He has something to tell you.'

The man's skin texture clearly indicated he was earning five times my monthly salary per hour even when he was eating lobster on the beach.

'It gives me great pleasure, on behalf of the Banco de Oceano e Rocha to make the following offer. If Inspector Coelho will accept the doctor's ruling and allow his beard to be shaved, this cheque made out for a total of three million escudos will join the sum already pledged for charity making a total fund of nearly six million escudos.'

You'd have thought Sporting had lifted the European Cup by the noise the crowd made. There was nothing to be done. Grace was imperative. Fifteen minutes later I looked like that rare thing—a Portuguese badger.

I was pretty well passed overhead to the bar A Bandeira Vermelha which was run by an old friend, António Borrego, who billed himself as the last communist in Portugal. The bank director was pressed in there with me, along with my daughter and the rest of my family and even the mayor found his way to my side with the microphone still in his top pocket.

António assembled the beers in glass-frosted ranks. He was a man who needed a meal, a lifetime of meals. The sort who couldn't put on weight if you sat a pig in his lap. He had a concave, white, hairy chest, eyes sunken deep into his head and untrained eyebrows off the leash. His forearms were as wiry and covered in hair as a monkey's and he had a past I didn't know the half of.

Olivia, the fat man and myself took a beer each. António had his Polaroid out to record the event for his wall of bacchanalia.

'I wouldn't know you any more,' he said to me. 'I need a reference.'

I raised my glass. Tears rolled down the side. The emotional beer.

'With my first drink for 172 days,' I said, 'I propose a toast to the health and generosity of Senhor Miguel da Costa Rodrigues of the Banco de Oceano e Rocha.'

Olivia told me how she knew the banker. She was at school with his daughter and cut clothes for her mother. He was wearing one of her ties. He'd even offered to set her up in the fashion business. I told him I wanted her to finish her education. An expensive international school in Carcavelos paid for by her English grandparents who didn't want a granddaughter who couldn't speak their language. The banker sighed at a missed opportunity. Olivia sulked for show. We all had parts to play.

'A toast,' said Senhor Rodrigues, getting into the spirit, 'to Olivia Coelho for making all this possible.'

We drank again and Olivia planted a red 'O' on my new white cheek.

'One more thing,' I said to the packed bar buzzing with beer, 'who fixed the scales?'

There were two seconds of frost-britde silence until I smiled, a glass smashed and the barber came in with a plastic bag which he presented to me.

'Your clippings,' he said weighing it with a kiss. 'A two-kilo bed for your cat.'

'Don't tell me that now.'

'It must have been what you had living in there that weighed,' said the mayor. We all looked at him. He fingered his microphone. António put three more beers on the counter. Olivia and I turned into each other.

'Me?' I said to her quietly. 'I think it was the past all tangled up in it.'

She licked a finger and wiped the lipstick off my cheek, her eyes brim-full for a moment.

'You're right,' said António, suddenly between us, 'history's a weight, a dead weight too ... isn't that right Senhor Rodrigues?'

Senhor Rodrigues belched politely into his hand, not used to proletarian drink.

'History repeats itself,' he said and even António laughed—the communist who can smell the pork meat of a capitalist when they're roasting him as far away as the Alentejo.

'You're right,' said António. 'History's only a weight to those that lived it. For the next generation it's no heavier than a few school books and forgotten with a glass of beer and the latest CD.'

'Eh, António,' I said, 'have a beer yourself. It's Friday night, tomorrow's your saint's day, the poor people of Paço de Arcos are nearly six million better off and I'm back on the drink. The new history.'

António smiled and said: To the future.'

We all went out to eat that night, even Senhor Rodrigues who might not have been used to the metal tables and chairs but appreciated the food. It was the meal my stomach had growled over for six months. Ameijoas à Bulhão Pato, clams in white wine, garlic and fresh coriander, robalo grelhado, grilled sea bass caught off the cliffs at Cabo da Roca that morning, borrego assado, Alentejo lamb cooked until it's falling apart. Red wine from Borba. Coffee as strong as a mulatto's kiss. And to finish aguardente amarela, the yellow fiery one.

Senhor Rodrigues left for his house in Cascais at the aguardente stage. Olivia went to a club in Cascais with a bunch of her friends soon after. I gave her the taxi fare home. I drank two more amarelinhas and went to bed with a litre of water inside me and two aspirins, the pillow soft and cool against my naked burning cheeks.

I woke in the night for ten seconds, confused in the darkness and feeling as big and as solid as the central pillar in a motorway bridge. I'd dreamt luridly but one image stuck—a cliff-top walk in the dark of an evening, a sheer drop close by somewhere, the sea roar out there, its saltine prickle bursting up from the rocks below. Fear, apprehension and excitement rose up and I fell into more sleep.

It was at about that time that a girl started to make her dent in the sand no more than a few hundred metres away from where I was sleeping. Her eyes wide open, she moonbathed to a night full of stars, her blood slack, her skin cold and hard as fresh tuna.

Chapter II

Saturday, 13th June 199–, Paço de Areas, near Lisbon

Plates were crashing on to a marble floor. Plates were crashing and smashing and endlessly shatter

ing on the marble floor. I surfaced into the brutal noise, the harshest reality there is, of a phone going off in a hangover at 6.00 a.m. I wrenched the handset to my ear. The blissful silence, the faint sea hiss of a distant mobile. My boss Eng. Jaime Leal Narciso gave me a good morning and I tried to find some moisture in my beak to reply.

'Zé?' he asked.

'Yes, it's me,' I said, which came out in a whisper as if I had his wife next to me.

'You're all right then,' he said, but didn't wait for the reply. 'Look, the body of a young girl's been found on the beach at Paço de Arcos and I want...'

Those words trampolined me off the bed, the phone jack yanked the handset from my grip and I cannoned off the door frame into the hall. I thundered down the distressed strip of carpet and wrenched the door open. Her clothes lay in a track from the door to the bed—clumpy big-heeled shoes, black silk top, lilac shirt, black bra, black flares. Olivia was twisted into her sheet face down, her bare arms and shoulders spread, her black hair, as soft and shiny as sable, splashed across the pillow.

I drank heavily in the bathroom until my belly was taut with water. I snatched the phone to my ear and lay down on the bed again.

'Bom dia, Senhor Engenheiro,' I said, addressing him by his degree in science, as was usual.

'If you'd given me two seconds I'd have told you she was blonde.'

'I should have checked last night but...' I paused, synapses clashed painfully, 'why are you calling me at six in the morning to tell me about a body on the beach? Throw your mind back to the weekend roster and you'll find I'm off duty.'

'Well, the point is you're two hundred metres from the situation and Abílio, who is on duty, lives in Seixal which as you know ... It would be...'

'I'm in no condition to...' I said, my brain still blundering around.

'Ah yes. I forgot. How was it? How are you?'

'Cooler about the face.'