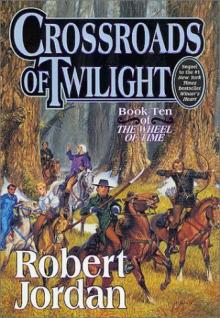

Crossroads of Twilight

Robert Jordan

Crossroads of Twilight

Wheel of Time 10

Robert Jordan

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

Chapter 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

EPILOGUE

GLOSSARY

And it shall come to pass, in the days when the Dark Hunt rides, when the right hand falters and the left hand strays, that mankind shall come to the Crossroads of Twilight and all that is, all that was, and all that will be shall balance on the point of a sword, while the winds of the Shadow grow.

- From The Prophecies of the Dragon translation believed done by Jain Charin, known as Jain Farstrider, shortly before his disappearance

PROLOGUE

Glimmers of the Pattern

Rodel Ituralde hated waiting, though he well knew it was the largest part of being a soldier. Waiting for the next battle, for the enemy to move, to make a mistake. He watched the winter forest and was as still as the trees. The sun stood halfway to its peak, and gave no warmth. His breath misted white in front of his face, frosting his neatly trimmed mustache and the black fox fur lining his hood. He was glad that his helmet hung at his pommel. His breastplate held the cold and radiated it through his coat and all the layers of wool, silk and linen beneath. Even Dart’s saddle felt cold, as though the white gelding were made of frozen milk. The helmet would have addled his brain.

Winter had come late to Arad Doman, very late, but with a vengeance. From summer heat that lingered unnaturally into fall, to winter’s heart in less than a month. The leaves that had survived the long summer’s drought had been frozen before they could change color, and now they glistened like strange, ice-covered emeralds in the morning sun. The horses of the twenty-odd arms-men around him occasionally stamped a hoof in the knee-deep snow. It had been a long ride this far, and they had farther to go whether this day turned out good or ill. Dark clouds roiled the sky to northward. He did not need his weather-wise there to tell him the temperature would plummet before nightfall. They had to be under shelter by then.

“Not as rough as winter before last, is it, my Lord?” Jaalam said quietly. The tall young officer had a way of reading Ituralde’s mind, and his voice was pitched for the others to hear. “Even so, I suppose some men would be dreaming of mulled wine about now. Not this lot, of course. Remarkably abstemious. They all drink tea, I believe. Cold tea. If they had a few birch switches, they’d be stripping down for snow baths.”

“They’ll have to keep their clothes on for the time being,” Ituralde replied dryly, “but they might get some cold tea tonight, if they’re lucky.” That brought a few chuckles. Quiet chuckles. He had chosen these men with care, and they knew about noise at the wrong time.

He himself could have done with a steaming cup of spiced wine, or even tea. But it was a long time since merchants had brought tea to Arad Doman. A long time since any outland merchant had ventured farther than the border with Saldaea. By the time news of the outside world reached him, it was as stale as last month’s bread, if it was more than rumor to begin. That hardly mattered, though. If the White Tower truly was divided against itself, or men who could channel really were being called to Caemlyn . . . well, the world would have to do without Rodel Ituralde until Arad Doman was whole again. For the moment, Arad Doman was more than enough for any sane man to go on with.

Once again he reviewed the orders he had sent, carried by the fastest riders he had, to every noble loyal to the King. Divided as they were by bad blood and old feuds, they still shared that much. They would gather their armies and ride when orders came from the Wolf; at least, so long as he held the King’s favor. They would even hide in the mountains and wait, at his order. Oh, they would chafe, and some would curse his name, but they would obey. They knew the Wolf won battles. More, they knew he won wars. The Little Wolf, they called him when they thought he could not hear, but he did not care whether they drew attention to his stature - well, not much - so long as they rode when and where he said. Very soon they would be riding hard, moving to set a trap that would not spring for months. It was a long chance he was taking. Complex plans had many ways to fall apart, and this plan had layers inside layers. Everything would be ruined before it began if he failed to provide the bait. Or if someone ignored his order to evade couriers from the King. They all knew his reasons, though, and even the most stiff-necked shared them, though few were willing to speak of the matter aloud. He himself had moved like a wraith racing on a storm since he received Alsalam’s latest command. In his sleeve where the folded paper lay tucked above the pale lace that fell onto his steel-backed gauntlet. They had one last chance, one very small chance, to save Arad Doman. Perhaps even to save Alsalam from himself before the Council of Merchants decided to put another man on the throne in his place. He had been a good ruler, for over twenty years. The Light send that he could be again.

A loud crack to the south sent Ituralde’s hand to the hilt of his longsword. There was a faint creak of leather and metal as others eased their weapons. For the rest, silence. The forest was as still as a frozen tomb. Only a limb breaking under the weight of snow. After a moment, he let himself relax - as much as he had relaxed since the tales came north of the Dragon Reborn appearing in the sky at Palme. Perhaps the man really was the Dragon Reborn, perhaps he really had appeared in the sky, but whatever the truth, those tales had set Arad Doman on fire.

Ituralde was sure he could have put out that fire, given a freer hand. It was not boasting to think so. He knew what he could do, with a battle, a campaign, or a war. But ever since the Council had decided the King would be safer smuggled out of Bandar Eban, Alsalam seemed to have taken into his head that he was the rebirth of Artur Hawkwing. His signature and seal had marked scores of battle orders since, flooding out from wherever the Council had him hidden. They would not say where that was, even to Ituralde himself. Every woman on the Council that he confronted went flat-eyed and evasive at any mention of the King. He could almost believe they did not know where Alsalam was. A ridiculous thought, of course. The Council kept an unblinking eye on the King. Ituralde had always believed the merchant Houses interfered too much, yet he wished they would interfere now. Why they remained silent was a mystery, for a king who damaged trade did not remain long on the throne.

He was loyal to his oaths, and Alsalam was a friend, besides, but the orders the King sent could not have been better written to achieve chaos. Nor could they be ignored. Alsalam was the King. But he had commanded Ituralde to march north with all possible speed against a great gathering of Dragonsworn that Alsalam supposedly knew of from secret spies, then ten days later, with no Dragonsworn yet in sight, an order came to move south again, with all possible speed, against another gathering that never materialized. He had been commanded to concentrate his forces to defend Bandar Eban when a three-pronged attack might have ended it all and to divide them when a hammer blow could have done the same, to harry ground he knew the Dragonsworn had abandoned, and to march away from where he knew they camped. Worse, Alsalam’s orders oft

en had gone directly to the powerful nobles who were supposed to be following Ituralde, sending Machir in this direction, Teacal in that, Rahman in a third. Four times, pitched battles had resulted from parts of the army blundering into one another in the night while moving to the King’s express command and expecting none but enemies ahead. And all the while the Dragonsworn gained numbers, and confidence. Ituralde had had his triumphs - at Solanje and Maseen, at Lake Somal and Kandelmar - the Lords of Katar had learned not to sell the products of their mines and forges to the enemies of Arad Doman - but always, Alsalam’s orders wasted his gains.

This last order was different, though. For one thing, a Gray Man had killed Lady Tuva trying to stop it from reaching him. Why the Shadow might fear this order more than any other was a mystery, yet it was all the more reason to move swiftly. Before Alsalam reached him with another. This order opened many possibilities, and he had considered every last one he could see. But the good ones all started here, today. When small chances of success were all that remained, you had to seize them.

A snowjay’s strident cry rang out in the distance, then a second time, a third. Cupping his hands around his mouth, Ituralde repeated the three harsh calls. Moments later a shaggy, pale dapple gelding appeared out of the trees, his rider in a white cloak streaked with black. Man and horse alike would have been hard to see in the snowy forest had they been standing still. The rider pulled up beside Ituralde. A stocky man, he wore only a single sword, with a short blade, and there were a cased bow and a quiver fastened to his saddle.

“Looks like they all came, my Lord,” he said in his permanently hoarse voice, pushing his cowl back from his head. Someone had tried to hang Donjel when he was young, though the reason was lost in the years. What remained of his short-cropped hair was iron-gray. The dark leather patch covering the socket of his right eye was a remnant of another youthful scrape. One eye or two, though, he was the best scout Ituralde had ever known. “Most, anyways,” he went on. “They put two rings of sentries around the lodge, one inside the other. You can see them a mile off, but nobody will get close without them at the lodge hearing of it in time to get away. By the tracks, they didn’t bring no more men than you said they could, not enough to count. Course,” he added wryly, “that still leaves you outnumbered a fair bit.”

Ituralde nodded. He had offered the White Ribbon, and the men he was to meet had accepted. Three days when men pledged under the Light, by their souls and hope of salvation, not to draw a weapon against another or shed blood. The White Ribbon had not been tested in this war, however, and these days some men had strange ideas of where salvation lay. Those who called themselves Dragonsworn, for instance. He had always been called a gambler, though he was not. The trick was in knowing what risks you could take. And sometimes, in knowing which ones you had to take.

Pulling a packet sewn into oiled silk from his boot top, he handed it to Donjel. “If I don’t reach Coron Ford in two days, take this to my wife.”

The scout tucked the packet somewhere beneath his cloak, touched his forehead, and turned his horse west. He had carried its like for Ituralde before, usually on the eve of battle. The Light send this was not the time Tamsin would have to open that packet. She would come after him - she had told him so - the first incident ever of the living haunting the dead.

“Jaalam,” Ituralde said, “let us see what waits at Lady Osana’s hunting lodge.” As he heeled Dart forward, the others fell in behind him.

The sun rose to its height and began again to descend as they rode. The dark clouds in the north moved closer, and the chill bit deeper. There was no sound but the crunch of hooves breaking through the snow crust. The forest seemed empty save for themselves. He did not see any of the sentries Donjel had spoken of. The man’s opinion of what could be seen from a mile differed from that of most. They would be expecting him, of course. And watching to make sure he was not followed by an army, White Ribbon or no White Ribbon. A good many of them likely had reasons they felt sufficient to feather Rodel Ituralde with arrows. A lord might pledge the White Ribbon for his men, but would all of those feel bound? Sometimes, there were chances you just had to take.

About midafternoon, Osana’s so-called hunting lodge loomed suddenly out of the trees, a mass of pale towers and slender, pointed domes that would have fitted well among the palaces of Bandar Eban itself. Her hunting had always been for men or power, her trophies numerous and noteworthy despite her relative youth, and the “hunts” that had taken place here would have raised eyebrows even in the capital. The lodge lay desolate, now. Broken windows gaped like mouths with jagged teeth. None showed a glimmer of light or movement. The snow covering the cleared ground around the lodge had been well trampled by horses, however. The ornate brass-bound gates of the main courtyard stood open, and he rode through without slowing, followed by his men. The horses’ hooves clattered on the paving stones, where the snow had been beaten to slush.

No servants came out to greet him, not that he had expected any. Osana had vanished early in the troubles that now shook Arad Doman like a dog shaking a rat, and her servants had drifted quickly to others of her house, taking whatever places they could find. These days, the masterless starved, or turned bandit. Or Dragonsworn. Dismounting in front of the broad marble stairway at the end of the courtyard, he handed Dart’s reins to one of his armsmen, and Jaalam ordered the men to take shelter where they could find it for themselves and the animals. Eyeing the marble balconies and wide windows that surrounded the courtyard, they moved as if expecting a crossbow bolt between the shoulder blades. One set of stable doors stood slightly ajar, but in spite of the cold, they divided themselves between the corners of the courtyard, huddling with the horses where they could keep watch in every direction. If the worst came, perhaps a few might make it out.

Removing his gauntlets, he tucked them behind his belt and checked his lace as he climbed the stairs with Jaalam. Snow that had been trodden underfoot and frozen again crackled beneath his boots. He refrained from looking anywhere but straight ahead. He must appear supremely assured, as though there were no possibility events should go other than as he expected. Confidence was one key to victory. The other side believing you were confident was sometimes almost as good as actually being confident. At the head of the stairs, Jaalam pulled open one of the tall, carved doors by its gilded ring. Ituralde touched his beauty spot with a finger to make sure it was in place - his cheeks were too cold to feel the black velvet star clinging - before he stepped inside. As self-assured as he would have been at a ball.

The cavernous entry hall was as icy as the outside. Their breath made feathered mists. Unlit, the space seemed already wreathed in twilight. The floor was a colorful mosaic of hunters and animals, the tiles chipped in places, as though heavy weights had been dragged over them, or perhaps dropped. Aside from a single toppled plinth that might once have held a large vase or a small statue, the hall was bare. What the servants had not taken when they fled had long since been looted by bandits. A single man awaited them, white-haired and more gaunt than when Ituralde had last seen him. His breastplate was battered, and his earring was just a small gold hoop, but his lace was immaculate, and the sparkling red quarter moon beside his left eye would have gone well at court, in better times.

“By the Light, be welcome under the White Ribbon, Lord Ituralde,” he said formally, with a slight bow.

“By the Light, I come under the White Ribbon, Lord Shimron,” Ituralde replied, making his courtesy in return. Shimron had been one of Alsalam’s most trusted advisors. Until he joined the Dragonsworn, at least. Now he stood high in their councils. “My armsman is Jaalam Nishur, honor bound to House Ituralde, as are all who came with me.”

There had been no House Ituralde before Rodel, but Shimron answered Jaalam’s bow, hand to heart. “Honor be to honor. Will you accompany me, Lord Ituralde?” he said as he straightened.

The great doors to the ballroom were gone from their hinges, though Ituralde c

ould hardly imagine bandits looting those. They left a tall pointed arch wide enough for ten men to pass. Within the windowless oval room, half a hundred lanterns of every size and sort beat at shadows, though the light barely reached the domed ceiling. Separated by a wide expanse of floor, two groups of men stood against the painted walls, and if the White Ribbon had induced them to leave off helmets, all two hundred or more were armored otherwise, and certainly no one had put aside his swords. To one side were a few Domani lords as powerful as Shimron - Rajabi, Wakeda, Ankaer - each surrounded by his cluster of lesser lords and sworn commoners and smaller clusters, of few as two or three, many containing no nobles at all. The Dragonsworn had councils, but no one commander. Still, each of those men was a leader in his own right, some counting their followers in scores, a few in thousands. None appeared happy to be where he was, and one or two shot glares across the floor, to where fifty or sixty Taraboners stood in one solid mass and scowled back. Dragonsworn they might all be, yet there was little love lost between Domani and Taraboners. Ituralde almost smiled at the sight of the outlanders, though. He had not dared to count on half so many appearing today.

“Lord Rodel Ituralde comes under the White Ribbon.” Shim-ron’s voice rang through the lantern shadows. “Let whoever may think of violence search his heart, and consider his soul.” And that was the end of formality.

“Why does Lord Ituralde offer the White Ribbon?” Wakeda demanded, one hand gripping the hilt of his longsword and the other in a fist at his side. He was not a tall man, though taller than Ituralde, but as haughty as if he held the throne himself. Women had called him beautiful, once. Now a slanting black scarf covered the socket of his missing right eye, and his beauty spot was a black arrowhead pointing at the thick scar running from his cheek up onto his forehead. “Does he intend to join us? Or ask us to surrender? All know the Wolf is bold as well as devious. Is he that bold?” A rumble rose among the men on his side of the room, part mirth, part anger.