Of Stegner's Folly

Richard S. Shaver

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Of Stegner's Folly

By Richard S. Shaver

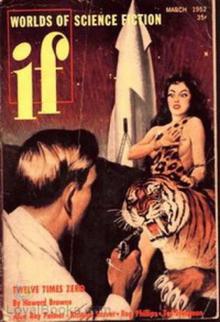

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from If Worlds of ScienceFiction March 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence thatthe U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

[Sidenote: _When a twenty-foot goddess walked out of the jungle, theyknew Stegner wasn't kidding._]

Old Prof Stegner never foresaw the complications his selectiveanti-gravitational field would cause. Knowing the grand old man as Idid, I can say that he never intended his "blessing" should become thecurse to mankind that it did. And the catastrophe it brought about wascertainly beyond range of all prophecy.

Of course, anyone who lived in 1972 and tried to get inside Stegner'sweird life-circle must agree that you can get too much of a good thing.Even a pumpkin can get too big--and that's what happened when the Profturned on his field--things got big; and too darned healthy!

I was there the day Stegner announced the results of ten year's researchon his selector. Nearly everyone present had read the sensationalarticles concerning his work in the feature sections of the big townnewspapers. Like the rest, I had a vague idea of what it was about. Itseemed the Prof had developed a device that repelled various particlesof matter without effecting others. In short, if he turned on hisgadget, gravity reversed itself for certain elements, and they went awayin a hurry. Like this: he could take oxide of iron, turn on hisselective repellor, and the rust rather magically turned to pure ironwithout the oxygen. Or, he could take a pile of mixed chemicals, turnhis control knobs to the elements known to be present in the mixture,and presto! Only certain ones, of his choosing remained. The atoms ofthe other elements conveniently left the vicinity.

All of which was interesting and extremely useful. The Prof promptly gotrich selling patent rights to the device, tuned to certain frequencieswhich refined heretofore unrefinable ores. His device made animprovement over most known methods of refining, costing far less inoperation than the standard and often complicated methods previously inuse.

Money gave the old man his opportunity. He fitted out a big research labin California, not too far from civilization, but secluded enough forsecrecy. Then he set about to try his selective repellor on livingtissues. His suspicion, that wonderful things could be discovered if hetuned his anti-gravitational field to the undesirable elements in thebody, was confirmed. Like lead poisoning--something no doctor can cureif it is severe. He found that he could cure a case of lead poisoningmerely by making the lead go away from there via the field. Morewonderful things began to come out of the Stegner laboratory, and hemade a lot more money.

Which was all very well indeed, only the Prof couldn't leave well enoughalone--he had to delve and pry. He had his own theories about diseaseand its cause, old age, and so on--all nuttier than a fruit cake. He wassomething of a crank on various health foods and diets that left outfoods raised with chemical fertilizers. He had an organic garden, agarden where no chemical fertilizer or poison spray was ever used. Andafter all, who knew better than the Prof--who could isolate them in atrice--how many poisons could be found accumulating in the average humanbody, consumed along with perfectly harmless foods during a lifetime?

Anyway, when the Prof called in the press, myself among them, he wasreally excited. "Gentlemen," he said, "I have solved the greatestmedical puzzle of all time. Before me, no medical man knew the cause ofold age. I have proved what the deterioration factor is, and I haveprovided a remedy--a sure and immediate remedy! The golden age ofmankind is here! Our life span can be greatly extended!"

I looked at Jake Heinz, my cameraman. Jake winked at me, but I didn'trespond. I liked the Prof. Such a fine old gentleman, to go whacky fromso much success....

Jake took a few shots of the Prof's rabbits and guinea pigs, of the Profhimself, and of the apparatus he had constructed which he claimed droveout the causative poison of age; a poison he called a radioactiveisotope of Potassium. The other reporters, not having the soft heartsJake and I toted around, wrote him up as a joke; said right out theythought the old boy was blowing his top. Immortality! Hah! Theypresented the whole thing as a farce.

No reporters were ever more wrong than those smart buckos.

* * * * *

Some months after the Prof's little news conference was over andforgotten, an item of vast importance turned up. It seemed that aroundStegner's secluded retreat there was a line where things started. Whatkind of things? Well, up to that line, things were normal; but beyondit, grass got enormous, the ground was higher and softer. Trees forgotto shed their leaves. Animals flocked there to eat the lush grass, sothe Prof erected a ten-foot electrified fence around his land to keepout the hordes of rabbits, deer, mice and what have you that came tofeast off the new supply of better forage.

That was only the beginning. Some months later there came items abouthouseflies the size of walnuts hatching out around the Prof's retreat.Now a swarm of houseflies the size of walnuts is news, and Jake and Igot up there on the jump.

It was terrific! The flies were there all right, but so were a good manyother oversized creatures. Roosting in the trees were robins, bluebirds,and doves as large as turkeys. King-sized ducks waddled aboutimportantly, displaying pouter-pigeon crops from overeating. It was asif some god had drawn a line and said: "This is the new Eden, where allliving things will prosper terrifically."

You never saw a sight like it! Or did you? Were you one of the horde whostarted camping around the Prof's magic circle trying to get permissionto enter?

It was then we got proof that it pays to be kind. Of all thenews-grabbers who surrounded the Prof's big wire gate, Jake and I werethe only ones who got in. The old man had not forgotten who had takenhim seriously and who had made fun of him.

Jake snapped a series of startling pics of the oversized animals andbirds. I interviewed the Prof again, even got his maid, Tilda'sopinions, and wrote it up as unsensationally as possible, playing downthe tremendous potential for trouble, playing up the really effectivemethod the old scientist had discovered for "eliminating thedeterioration factor" in life. I could see where the world was in forsome changes, and the going was going to be rough enough for the old manwithout making it worse. But my efforts came to naught when the picsJake had taken reached the editor's desk. He hit the ceiling, called meon the carpet, wanted to know where my news sense had gotten lost. Thenhe sent out three other smart boys to do a _good_ job on it.

The paper got out a special edition--and the troubles I had foreseenbegan. First, the government stepped in, trying to hush-hush the wholething; but too late. The rush had started. For miles around the poorProf's fenced-in hideaway, cars and trailers parked in a mad senselessjumble. People crowded against the fences and the electricity had to beshut off. Some smart aleck produced wire cutters and made an opening.The invasion of the new Eden had begun.

Stegner took flight, taking his secret apparatus and files with him. Hedeclined police escort, and vanished from his mad Eden. Where he wentwas impossible to learn, but I supposed the government knew.

The area he had revitalized with his selective field was a nine dayswonder, and after just about that long it was a tramped over, paperstrewn, garbage littered wreck. The oversized animals and birds driftedaway, the huge houseflies perished or were eaten by the birds.Apparently that was the end of the thing. Humanity had triumphed overits savior with its usual stupid interference.

A few of us remembered, could not put out of our minds the significanceof what the old man had done. He had pointed the way to a lushimmortality, and he had been shoved aside and pawed ove

r and writtenabout like some freak. If he had been a notorious criminal, he wouldhave gotten far better journalistic treatment.

But the years went by--four, five of them. And nothing more was heard ofStegner and his work. Until, one day coming home from a night shift onthe paper, I found a letter in my box. It was a rather plain lookingenvelope, but much larger than the ordinary. The handwritten address wasquite legible, but very big, as if a giant hand had cramped itself toproduce ordinary script:

_Dear old friend:_

_You may have forgotten me, but I do not forget you. If you would like to join me for a time, insert a notice to Harry F in the personal column to that effect. I am trusting you to keep my secret._

_Stegner_

Needless to say, I inserted the notice.

* * * * *

A limousine, driven by a noncommittal chauffeur, picked me up off astreet corner, whisked me to the airfield. I