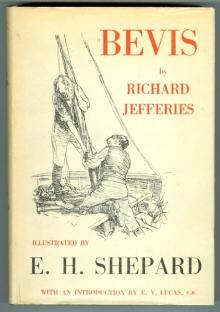

Bevis: The Story of a Boy

Richard Jefferies

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

BevisThe Story of a BoyBy Richard JefferiesPublished by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington,London. This edition dated 1882.Volume One, Chapter I.

BEVIS AT WORK.

One morning a large wooden case was brought to the farmhouse, and Bevis,impatient to see what was in it, ran for the hard chisel and the hammer,and would not consent to put off the work of undoing it for a moment.It must be done directly. The case was very broad and nearly square,but only a few inches deep, and was formed of thin boards. They placedit for him upon the floor, and, kneeling down, he tapped the chisel,driving the edge in under the lid, and so starting the nails. Twice hehit his fingers in his haste, once so hard that he dropped the hammer,but he picked it up again and went on as before, till he had loosenedthe lid all round.

After labouring like this, and bruising his finger, Bevis wasdisappointed to find that the case only contained a picture which mightlook very well, but was of no use to him. It was a fine engraving of"An English Merry-making in the Olden Time," and was soon hoisted up andslung to the wall. Bevis claimed the case as his perquisite, and beganto meditate what he could do with it. It was dragged from the houseinto one of the sheds for him, and he fetched the hammer and his ownspecial little hatchet, for his first idea was to split up the boards.Deal splits so easily, it is a pleasure to feel the fibres part, butupon consideration he thought it might do for the roof of a hut, if hecould fix it on four stakes, one at each corner.

Away he went with his hatchet down to the withy-bed by the brook (wherehe intended to build the hut) to cut some stakes and get them ready.The brook made a sharp turn round the withy-bed, enclosing a tongue ofground which was called in the house at home the Peninsula, because ofits shape and being surrounded on three sides by water. This piece ofland, which was not all withy, but partly open and partly copse, wasBevis's own territory, his own peculiar property, over which he wasautocrat and king.

He flew at once to attack a little fir, and struck it with the hatchet:the first blow cut through the bark and left a "blaze," but the seconddid not produce anything like so much effect, the third, too, rebounded,though the tree shook to its top. Bevis hit it a fourth time, not atall pleased that the fir would not cut more easily, and then, fancyinghe saw something floating down the stream, dropped his hatchet and wentto the edge to see.

It was a large fly struggling aimlessly, and as it was carried past aspot where the bank overhung and the grasses drooped into the water, afish rose and took it, only leaving just the least circle of wavelet.Next came a dead dry twig, which a wood-pigeon had knocked off with hisstrong wings as he rose out of the willow-top where his nest was. Thelittle piece of wood stayed a while in the hollow where the brook hadworn away the bank, and under which was a deep hole; there the currentlingered, then it moved quicker, till, reaching a place where thechannel was narrower, it began to rush and rotate, and shot past a longgreen flag bent down, which ceaselessly fluttered in the swift water.Bevis took out his knife and began to cut a stick to make a toy boat,and then, throwing it down, wished he had a canoe to go floating alongthe stream and shooting over the bay; then he looked up the brook at theold pollard willow he once tried to chop down for that purpose.

The old pollard was hollow, large enough for him to stand inside on thesoft, crumbling "touchwood," and it seemed quite dead, though there weregreen rods on the top, yet it was so hard he could not do much with it,and wearied his arm to no purpose. Besides, since he had grown biggerhe had thought it over, and considered that even if he burnt the treedown with fire, as he had half a mind to do, having read that that wasthe manner of the savages in wild countries, still he would have to stopup both ends with board, and he was afraid that he could not make itwater-tight.

And it was only the same reason that stayed his hand from barking an oakor a beech to make a canoe of the bark, remembering that if he got thebark off in one piece the ends would be open and it would not floatproperly. He knew how to bark a tree quite well, having helped thewoodmen when the oaks were thrown, and he could have carried the shortladder out and so cut it high enough up the trunk (while the treestood). But the open ends puzzled him; nor could he understand nor getany one to explain to him how the wild men, if they used canoes likethis, kept the water out at the end.

Once, too, he took the gouge and the largest chisel from the workshop,and the mallet with the beech-wood head, and set to work to dig out aboat from a vast trunk of elm thrown long since, and lying outside therick-yard, whither it had been drawn under the timber-carriage. Now,the bark had fallen off this piece of timber from decay, and the surfaceof the wood was scored and channelled by insects which had eaten theirway along it. But though these little creatures had had no difficulty,Bevis with his gouge and his chisel and his mallet could make verylittle impression, and though he chipped out pieces very happily forhalf an hour, he had only formed a small hole. So that would not do; heleft it, and the first shower filled the hole he had cut with water, andhow the savages dug out their canoes with flint choppers he could notthink, for he could not cut off a willow twig with the sharpest splinterhe could find.

Of course he knew perfectly well that boats are built of plank, but ifyou try to build one you do not find it so easy; the planks are not tobe fitted together by just thinking you will do it. That was moredifficult to him than gouging out the huge elm trunk; Bevis could hardlysmooth two planks to come together tight at the edge or even to overlap,nor could he bend them up at the end, and altogether it was a verycross-grained piece of work this making a boat.

Pan: the spaniel, sat down on the hard, dry, beaten earth of theworkshop, and looked at Bevis puzzling over his plane and his pencil,his footrule, and the paper on which he had sketched his model; then upat Bevis's forehead, frowning over the trouble of it; next Pan curledround and began to bite himself for fleas, pushing up his nostril andsnuffling and raging over them. No. This would not do; Bevis could notwait long enough; Bevis liked the sunshine and the grass under foot.Crash fell the plank and bang went the hammer as he flung it on thebench, and away they tore out into the field, the spaniel rolling in thegrass, the boy kicking up the tall dandelions, catching the yellow diskunder the toe of his boot and driving it up in the air.

But though thrown aside like the hammer, still the idea slumbered in hismind, and as Bevis stood by the brook, looking across at the old willow,and wishing he had a boat, all at once he thought what a capital raftthe picture packing-case would make! The case was much larger than thepicture which came in it; it had not perhaps been originally intendedfor that engraving. It was broad and flat; it had low sides; it wouldnot be water-tight, but perhaps he could make it--yes, it was just thevery thing. He would float down the brook on it; perhaps he would crossthe Longpond.

Like the wind he raced back home, up the meadow, through the garden,past the carthouse to the shed where he had left the case. He tilted itup against one of the uprights or pillars of the shed, and then stoopedto see if daylight was visible anywhere between the planks. There weremany streaks of light, chinks which must be caulked, where they did notfit. In the workshop there was a good heap of tow; he fetched it, andimmediately began to stuff it in the openings with his pocket-knife.Some of the chinks were so wide, he filled them up with chips of wood,with the tow round the chips, so as to wedge tightly.

The pocket-knife did not answer well. He got a chisel, but that cut thetow, and was also too thick; then he thought of an old table-knife hehad seen lying on the garden wall, left there by the man who had beenset to weed the path with it. This did much better, but it was tediouswork, very tedious work; he was obliged to leave it twice--once to havea swing, and stretch himself; the sec

ond time to get a hunch, or cog, ashe called it, of bread and butter. He worked so hard he was so hungry.Round the loaf there were indentations, like a cogged wheel, such as themillwright made. He had one of these cogs of bread cut out, and wellstuck over with pats of fresh butter, just made and fresh from thechurn, not yet moulded and rolled into shape, a trifle salt butdelicious.

Then on again, thrusting the tow in with the knife, till he had used itall, and still there were a few chinks open. He thought he would getsome oakum by picking a bit of rope to pieces: there was no old ropeabout, so he took out his pocket-knife, and stole into the waggon-house,where, first looking round to be sure that no one was about, he slashedat the end of a cart-line. The thick rope was very hard, and it wasdifficult to cut it; it was twisted so tight, and the rain and the sunhad toughened it besides, while the surface was case-hardened by rubbingagainst the straw of the loads it had bound. He haggled it off at last,but when he tried to pick it to pieces he found the