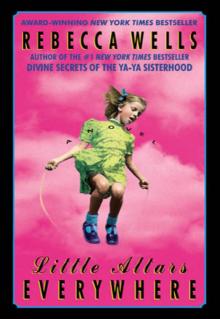

Little Altars Everywhere

Rebecca Wells

Rebecca Wells

Little Altars Everywhere

To THOMAS SCHWORER, my beloved

THOMAS WELLS, my brother

T.G., my guide

and

LODI, my home soil

Everything in life that we really accept

undergoes a change.

So suffering must become love.

That is the mystery.

—KATHERINE MANSFIELD

Contents

Epigraph

Note to the Reader Siddalee, 1991

Ooh! My Soul

Part One

Wilderness Training Siddalee, 1963

Choreography Siddalee, 1961

Wandering Eye Big Shep, 1962

Skinny-Dipping Baylor, 1963

Bookworms Viviane, 1964

Cruelty to Animals Little Shep, 1964

Beatitudes Siddalee, 1963

The Elf and the Fairy Siddalee, 1963

The Princess of Gimmee Lulu, 1967

Hair of the Dog Siddalee, 1965

Part Two

Willetta’s Witness Willetta, 1990

Snuggling Little Shep, 1990

Catfish Dreams Baylor, 1990

E-Z Boy War Big Shep, 1991

Playboys’ Scrapbook Chaney, 1991

Looking for My Mules Viviane, 1991

The First Imperfect Divine Compassion Baptism Video Siddalee, 1991

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Rebecca Wells

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Note to the Reader

I’ve been thinking lately about the intimacy that exists between us, writer and reader. And the more I reflect, the more grateful I am for this gift, because the process of a book’s coming to life is not fully complete until your imagination meets mine on the page. The words evoke pictures and something altogether new is created, something different from the limits of my own skills and imagination. Something that is a marriage between your heart, mind, and body—and mine.

Although inspiration is assumed to be essential to art, in fact, all life requires inspiration. Inspiration: literally “to breathe in.” To breathe in the life-giving oxygen we need, and also to breathe in whatever divine breath our bodies can receive. When you enter the world of a book I have written, our breaths intermingle, along with whatever celestial breeze might bless our exchange. Breathing in, breathing out; in so doing, if we are lucky or blessed, it all comes to life!

The whole idea of possessing creative work is perhaps as absurd as the ownership of rivers and trees. Helpers and co-conspirators meet me at every turn. I’m graced with all sorts of comfort and aid from my motley crew of angels. Spirits, born and unborn; people near and far, trees; dahlias; the smell of gumbo on the back burner; my cocker spaniel, Lulu; my husband who is sent straight from the Holy Lady as a gift to me, making up for all that is wobbly, wrecked, or lost. Once you, the reader, encounter the words on the page, the alphabet has meaning. So “my” work also becomes “yours.”

My closest friends have been known to call me “Rebecca It-Takes-a-Village Wells.” They know firsthand what it takes to write a book—at least for me. I never claimed to be a low-maintenance gal, but when I’m writing, it’s particularly challenging. I lose things constantly: my watch, my glasses, my papers, my mind. The image of a writer as a solitary person who does it all alone is an illusion, or perhaps a delusion. Too little has been written about the contributions of a writer’s loved ones, especially partners, in the creation of a book. Their sight, their touch, their ears, their belief, their patience, the food they hand out to put into mouths when we have forgotten food was necessary—those we love, those who love us, contribute to our work in ways too countless, too precious to explain.

Little Altars Everywhere began as a single short story. I based “Looking for my Mules” on a tale told to me by a person I love dearly. I was working as a playwright and actor while I was writing the story. “You’re no writer,” sneered the inner critic who tries to sabotage my every move. “You’re just a theater person. Who do you think you’re kidding?” I wrote “Looking for My Mules” anyway, and a blessed, small literary magazine picked it up, giving me a boost in confidence that I desperately needed.

Slowly, over many years, other chapters began to grow. Then, while performing a burlesque dance in my play Gloria Duplex wearing four-inch spike heels, I came out of a flying dismount, landed off-balance, and broke a tiny bone in my left foot called the sesamoid. Small as this bone is, it serves a crucial purpose: it acts for the foot as the knee does for the leg. It hurt to walk. It hurt to stand. It hurt to sleep with a heavy blanket covering my feet. It hurt too much to be onstage. I was sidelined until my foot healed, which took more time than I can bear to think about, even now. I had worked for years to get where I was, and this was devastating to me as a professional actor. You can’t afford to be out of the loop. You must be seen, you can’t turn down role after role and still expect them to call.

It was scary, depressing, and lonely to lose the career I had trained for and nurtured my entire life in one way or the other. That broken bone forced me to quiet down, sit still, and write, something I’ve always had trouble doing, because the actor body I inhabit longs to stay in constant motion.

Hidden blessings inside suffering. This is ultimately what Little Altars Everywhere is about. We are given our lives, our fear, our broken bones, and broken hearts. Breaks create openings that were not there before, and in that space grow the seeds for new creation.

So that at the dark center of suffering that suffuses Little Altars Everywhere lies both the luminance of blessing, as well as the seeds for my second book, Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood.

Little Altars Everywhere was originally published by a tiny Northwest press. They gave me the biggest gift anyone could have: the perfect editor for the manuscript, Mary Helen Clarke. We met every Saturday morning at my home on the island, consuming gallons of coffee and tea and baskets of yummies from the local bakery. We stretched out on my bed with drafts of chapters covering every square inch, and howled with laughter over bits we thought were funny. Then we’d try to come up with something even funnier. The sadness we did not have to work on. It came, as sadness usually does, as soon as I sat down and began to listen.

The small press had a correspondingly small budget for publicity, so my husband, our best friend, and I became a public relations firm, and did our damnedest to promote the book. We made up a letterhead on our Mac, maxed out our credit cards at the copy shop, and hit the local and regional media for all we were worth. I’d make follow-up calls to radio and TV and newspapers, pretending to be a secretary just “following up on the Rebecca Wells material we sent you.” I have given thanks for my background as an actor more than once!

Receiving the Western States Book Award for Little Altars Everywhere brought some money into the coffers of the small press, and helped the book along, not to mention giving me a surge of optimism. Then booksellers began their big-hearted word-of-mouth campaign to sell my book, and I learned to love booksellers as much as I had always loved librarians—book friends, too many to count.

With the publication of Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, Little Altars Everywhere was reissued in paperback, and now, to my great joy, in hardcover. People ask me how I feel, and I say “Happy!” Or, more accurately, I say, “A big fat beautiful gift has dropped into my lap, and I hope I know how to treat it right.”

I continue to be awestruck and honored by the generosity readers have shown me in sharing their feelings about my books. Especially the gift of extraordinary and heartfelt letters! The wisdo

m and goodwill of the eighty-three-year-old woman in a tiny town in Minnesota who wrote me to say, “At first I was not going to get your book because the title was so strange. But one of my favorite books also has a strange title. So I read yours. Then I gave it to all four of my daughters. You keep going. I’m going to write Opry [sic] and tell her about your books.” I received this letter when my book had sold approximately twenty-seven copies.

Or the man in Olympia, Washington, who wrote to me with the exact words I craved as the books began selling. “In case you ever wonder if your success is deserved, as humans often do, my vote says it is.” I do not know if this reader will ever know how his response tapped into a deep fear in me, acknowledged it, and then comforted me. For whether he is right or wrong, whether we “deserve” anything, he reminded me that I am part of a beloved community that stretches out farther than I can see. This has been the greatest blessing of having my books read widely: the knowledge that I am not so alone, that I am not as orphaned as I once feared. How can a person ask for more than that?

Then there’s the joy of meeting readers face to face. I’ve met people who have changed my life forever—sometimes simply by the inscription that they ask me to pen into their copy of my book. I’ve met people who know so much more than I do, and they continue to tell me what it is that I have written. Because when you’re writing, you are not fully aware of what you are writing. You have no answers. In fact, you’re lucky if you can remember the questions. Readers find clues, and if you’re fortunate, they share them with you.

We are worked on by the work we are helped to create. Compassion works on us, acceptance works on us. If we can see past the myopic confines of the ego that aggressively believes that it alone is responsible for each act of creativity—nay, for life itself—then it is possible to recognize the bounteous goodness and generosity that pours into the making of your fiction as well as your life.

All creativity is a gift. All life is a gift. And what a fetching ecosystem it is. I am given a gift. I am helped to hand it on to you, reader, in the form of a book. As you read, you keep the gift moving, and then hand a new gift back to me—the gift of having been met, of having been seen, of having been listened to.

And so I thank you for holding this book in your hands. My heart’s wish is that we both will see what Sidda does when she swings high on the backyard swing—that holy sparks do fly everywhere, especially between writers and readers.

Rebecca Wells

September, 1998

Ooh! My Soul

Siddalee, 1991

In my dream, I’m five years old again and it’s a summer night at our camp at Spring Creek. Mama and all us kids—me, Little Shep, Baylor, and Lulu—around a bonfire. Mama’s gang of girlfriends, the Ya-Yas, and all their kids are there too. Mama goes inside and puts Little Richard on the record player. She cranks the music up so loud it bounces off the pine trees. Then she comes back, takes my hand and says, Alright now, Siddalee: Dance!

Ooooh, My Soul! Little Richard begins, shouting out a warning for the weak of heart. And Mama’s already shaking, she’s boogying, she’s jukin, she’s slapping her thighs and rolling her hips like I’ve never seen her do before.

Baby baby baby baby, don’t you know my love is true?!

Ooooo!

Honey honey honey honey, get up offa that money!

That man sings nasty. Those horns blow nasty. My body takes over and I’m moving. Sunburned legs shuffle across the ground, head rolls around. I turn in circles, I face Mama and shake my shoulders and hips faster than the human eye can see. I shake so hard that freckles jump off my face.

Baby baby baby baby, don’t you know my love is true?!

Ooooo!

Honey honey honey honey, get up offa that money!

My hair flies in my face, it flies in my mouth. Mama stomps the earth with her feet, I can see her Rich Girl Red painted toenails against the dirt. I laugh, I spin, I almost stumble over the other kids—but when I do, they help me back up and I keep on dancing. Richard, Little Richard, he’s shining like a shooting star, he’s the hottest thing in the Louisiana night sky. He hollers right up into my four-foot frame, he wails and horns blow, oh those horns blow!

Love love love love love

Ooooh my soul!

Arms and legs have new lives all their own. Every single part of me dances. And that 45-rpm record plays over and over and over, and we’re singing with Little Richard now, we’re blowing saxophones! And if Daddy drives up in his pickup, you know he’d yell at us, white women dancing like that, you know he would! But Daddy doesn’t drive up, and me and Mama go on dancing and all the Ya-Yas and the rest of the kids are yelling and clapping for us! Oh, they yell and clap and hoot and holler! And I know—you can’t tell me different: something secret, something sweet, something strong is shooting up from the earth straight into my body, making my limbs quiver, making me crazy-dance all over the place right there in my orange and white sunsuit.

When I wake up from my dream, I’m laughing and my face is streaked with tears. My body feels relaxed, loose, good. And for a minute, I swear I feel Mama in the room. Feel her Jergen’s-lotioned hands touching mine. The way they used to when I was little and she’d say, Come here dahling, I’ve rubbed on way too much, let me give you some moisturizer.

I roll over in bed and I’m 33 years older than in my dream, and I still want to hold Mama’s hands. I’m crying and I’m laughing and I still want my mother to come to me and take me in her arms.

Part One

Wilderness Training

Siddalee, 1963

One thing I really hate about Girl Scouts is those uniforms. They bring out my worst features—fat arms and short legs. Mama tries her best to give that drab green get-up some style, but I just get sent home with a note because the glitzy pieces of costume jewelry she pins on me are against regulations.

The only reason I joined Scouts in the first place was all because of merit badges. I wanted to earn more of those things than any other girl in Central Louisiana. I wanted my sash to be so heavy with badges that it would sag off my shoulder when I walked. There wouldn’t be any doubt about how outstanding I was. When I walked past the mothers waiting in their station wagons outside the parish hall, I wanted them to shake their heads in amazement. I wanted them to mutter, I just don’t know how in the world the child does it! That Siddalee Walker is such a superior Girl Scout.

I love going over and over the checklists for earning those badges in the Girl Scout Handbook. I have eight badges. More than M’lain Chauvin, who constantly tries to beat me in every single thing. I have got to keep my eye on that girl. She is one of my best friends, and we compete in everything from music lessons to telephone manners.

I was making real progress with my badges, and then our Girl Scout troop leader up and quit right after the Christmas holidays. She said she could no longer handle the stress of scouting. She didn’t even tell us herself—just sent a note to the Girl Scout bigwigs, and they cancelled our meetings until they could find someone to take us on.

And wouldn’t you know it, out of the wild blue, Mama and Necie Ogden decide to take things over and lead our troop. I could not believe my ears. Mama and Necie have been best friends since age five. Along with Caro and Teensy, they make up the “Ya-Yas.” The Ya-Yas drink bourbon and branch water and go shopping together. All day long every Thursday, they play bourrée, which is a kind of cutthroat Louisiana poker. When you get the right cards, you yell out “Bourrée!” real loud, slam your cards down on the table, then go fix another drink. The Ya-Yas had all their kids at just about the same time, but then Necie kept going and had some more. Their idol is Tallulah Bankhead, and they call everyone “Dahling” just like she did. Their favorite singer is Judy Garland or Barbra Streisand, depending on their moods. The Ya-Yas all love to sing. Also, the Ya-Yas were briefly arrested for something they did when they were in high school, but Mama won’t tell me what it was because she says I’m too young to comprehend.

At least Necie goes out and gets herself a Girl Scout leader’s outfit. Mama will not let anything remotely resembling a Scout-leader uniform touch her skin. She says, Those things are manufactured by Old Hag International. She says, If they insist on keeping those hideous uniforms, then they should change the name from “Girl Scouts” to “Neuter Scouts.”

Mama drew up some sketches of new designs for Girl Scout uniforms that she said were far more flattering than the old ones. But none of the Scout bigwigs would listen to her. So instead, she shows up at every meeting wearing her famous orange stretch pants and those huge monster sweaters.

The first official act of Mama and Necie’s reign is to completely scrap merit badges, because Mama says they make us look like military midgets.

Whenever I gripe about being cut off just as I was about to earn my Advanced Cooking badge, Mama says, Zip it, kiddo. Don’t ever admit you know a thing about cooking or it’ll be used against you in later life.

Now at our meetings, instead of working on our Hospitality, Music, and Sewing badges, they have us work on dramatic readings. They make us memorize James Whitcomb Riley and Carl Sandburg poems and then Mama coaches us on how to recite them. She calls out, Enunciate, dahling! Feel it! Feel it! Love those words out into the air!

All my popular girlfriends look at me like: Oh, we never knew you came from a nuthouse. I just lie and tell them Mama used to be a Broadway actress, when all she ever really did in New York was model hats for a year until she got lonely enough to come home and marry Daddy.