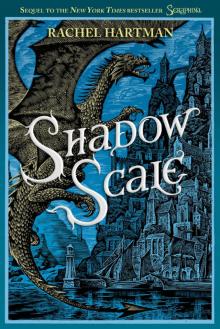

Shadow Scale

Rachel Hartman

Also by Rachel Hartman

Seraphina

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2015 by Rachel Hartman

Jacket art copyright © 2015 by Andrew Davidson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York. Random House and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouseteens.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hartman, Rachel.

Shadow scale / Rachel Hartman.—First edition.

pages cm.

Summary: “Seraphina, half-dragon and half-human, searches for others like her who can make the difference in the war between dragons and humans in the kingdom of Goredd.”

—Provided by publisher

ISBN 978-0-375-86657-9 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-375-96657-6 (lib. bdg.) —

ISBN 978-0-375-89659-0 (ebook) — ISBN 978-0-553-53381-1 (intl. tr. pbk.)

[1. War—Fiction. 2. Dragons—Fiction. 3. Courts and courtiers—Fiction. 4. Fantasy.] I. Title.

PZ7.H26736Sh 2015 [Fic]—dc22 2014017953

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For Byron

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

From Father Fargle’s Goredd: The Tangled Thicket of History

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Cast of Characters

Glossary

From Father Fargle’s Goredd:

THE TANGLED THICKET OF HISTORY

Let us first consider the role of Seraphina Dombegh in the events leading up to Queen Glisselda’s reign.

Nearly forty years after Ardmagar Comonot and Queen Lavonda the Magnificent signed their historic treaty, the peace between dragons and humans was still dangerously fragile. In Lavondaville, the Sons of St. Ogdo preached anti-dragon rhetoric on street corners, fomented unrest, and committed violence against saarantrai. These dragons in human form were easily identified in those days by the bells they were forced to wear; for their own protection, saarantrai and their lizard-like cousins, the quigutl, were shut up in the neighborhood called Quighole every night, but this only served to single them out further. As the peace treaty’s anniversary—and Ardmagar Comonot’s state visit—neared, tensions mounted.

A fortnight before the Ardmagar was to arrive, tragedy struck. Queen Lavonda’s only son, Prince Rufus, was murdered in classic draconic fashion: decapitation. His head, presumably eaten, was never found. Had a dragon truly killed him, though, or was it the Sons of St. Ogdo, hoping to inflame anti-dragon sentiment?

Into this thicket of politics and prejudice entered Seraphina Dombegh, newly hired assistant to the court composer, Viridius. The word abomination has fallen out of favor, but that is precisely what the people of Goredd would have considered Seraphina, for her mother was a dragon, her father a human. Had this secret been known, it could have meant Seraphina’s death, so her father kept her isolated for her own safety. Silver dragon scales around her waist and left forearm might have given her away at any time. Whether it was loneliness or her musical talent that drove her, she took a terrible risk in leaving her father’s house for Castle Orison.

Scales were not her only worry. Seraphina was also afflicted with maternal memories and visions of grotesque beings. Her maternal uncle, the dragon Orma, taught her to create within her mind a symbolic garden wherein she might house these curious beings; only by tending this garden of grotesques every night did she prevent visions from overtaking her.

Around the time of Prince Rufus’s funeral, however, three denizens of Seraphina’s mental garden overtook her in real life: Dame Okra Carmine, the Ninysh ambassador; a Samsamese piper called Lars; and Abdo, a young Porphyrian dancer. Seraphina eventually realized that these people were half-dragons like herself, that she was not alone in the world. They all had scales and peculiar abilities, mental or physical. It must have been both a relief and an additional worry. None of them were safe, after all. Lars, notably, was threatened on numerous occasions by Josef, Earl of Apsig, his dragon-hating half brother and a member of the Sons of St. Ogdo.

Seraphina might still have kept herself clear of politics and intrigue if not for her uncle Orma. For most of her life, he’d been her only friend, teaching her not merely how to control her visions but also music and draconic lore. Seraphina, in turn, had inspired in Orma an avuncular fondness, a depth of feeling deemed unacceptable by dragonkind. The draconic Censors, convinced that Orma was emotionally compromised, had hounded him for years, threatening to have him sent back to the dragons’ homeland, the Tanamoot, for the surgical removal of his memories.

After Prince Rufus’s funeral, Orma learned that his father, the banished ex-general Imlann, was in Goredd. Orma believed, and Seraphina’s maternal memories confirmed, that Imlann was a threat to Ardmagar Comonot, part of a cabal of disgruntled generals who wished to destroy the peace with Goredd. Wary of the Censors, Orma did not trust himself to be impartial and unemotional about his own father. He asked Seraphina to report Imlann’s presence to Prince Lucian Kiggs, Captain of the Queen’s Guard. Though Seraphina would have liked to remain inconspicuous, she could not refuse her beloved uncle’s request.

Did she approach Prince Lucian Kiggs with trepidation? Any sensible person would have. The prince had a reputation for being a perceptive and dogged investigator; if anyone at court was likely to uncover her secret, it was surely he. However, Seraphina had three unanticipated advantages. First, she had already come to his attention, favorably if unintentionally, as a patient harpsichord teacher to his cousin and fiancée, Princess Glisselda. Second, Seraphina had repeatedly found herself in a position to help people at court understand dragonkind, and the prince was grateful for her intercession. Finally, Prince Lucian, being the Queen’s bastard grandson, had never felt quite comfortable at court; in Seraphina, he recognized a fellow outsider, even if he could not precisely identify why.

He believed her report about Imlann, even as he discern

ed that she was leaving certain things unsaid.

Two banished knights—Sir Cuthberte and Sir Karal—came to the palace with news that they’d seen a rogue dragon in the countryside. Seraphina suspected it was Imlann. Prince Lucian Kiggs accompanied her to the knights’ secret enclave to see if anyone could positively identify the rogue. Ancient Sir James recalled the dragon as “General Imlann” from an attack forty years prior. While they were there, Sir James’s squire, Maurizio, demonstrated the dying martial art of dracomachia. Developed by St. Ogdo himself, dracomachia had once given Goredd the tools to battle dragons, but the art was now practiced by only a few. Seraphina realized how helpless humankind would be if the dragons broke the treaty.

Whether Imlann, in all his scaly, flaming horror, actually revealed himself to Seraphina and Prince Lucian on the road home or whether that episode is mere legend and embellishment is still a matter of scholarly debate. It is clear, however, that Seraphina and the prince became convinced that Imlann had killed Prince Rufus. They began to suspect that the wily old dragon was hiding at court in human form. Seraphina’s warnings to Ardmagar Comonot, however, fell on deaf ears. The Ardmagar, though he had co-authored the peace, was arrogant and unsympathetic, not yet the dragon he would become in later years.

Imlann struck on Treaty Eve, giving poisoned wine to Princess Dionne, Princess Glisselda’s mother. (Though the wine was also intended for Comonot, there is no evidence, contrary to some of my colleagues’ assertions, that Princess Dionne and Comonot were engaged in an illicit love affair.) Seraphina and Prince Lucian prevented Princess Glisselda from drinking the wine, but Queen Lavonda was not so fortunate.

Let this be a lesson about the patience of dragons: Imlann had been at court for fifteen years, disguised as Princess Glisselda’s governess, a trusted advisor and friend. Seraphina and Prince Lucian, realizing the truth at last, confronted Imlann, whereupon he seized Princess Glisselda and fled.

All the half-dragons had a role to play in Imlann’s capture and death: Dame Okra Carmine’s premonitions helped Seraphina and Prince Lucian find him; Lars distracted him with bagpipes so that Prince Lucian could rescue Princess Glisselda; and young Abdo squeezed Imlann’s still-soft throat, preventing him from spitting fire. Seraphina delayed Imlann’s escape by revealing the truth about herself, that she was his granddaughter, giving Orma time to transform. Orma was no match for Imlann, alas, and was badly injured. It was another dragon, Undersecretary Eskar of the dragon embassy, who finished Imlann off, high above the city.

History has shown that Imlann was indeed part of a cabal of dragon generals determined to overthrow Comonot and destroy the peace. While he wreaked havoc in Goredd, the others staged a coup in the Tanamoot, seizing control of the dragon government. The generals, who later styled themselves the “Old Ard,” sent the Queen a letter declaring Comonot a criminal and demanding that Goredd turn him over at once. Queen Lavonda was incapacitated by poison, and Princess Dionne was dead. Princess Glisselda, in her first act as Queen, decided that Goredd would not return Comonot to face trumped-up charges and that, if necessary, Goredd would go to war for peace.

If your historian may be permitted a personal note: some forty years ago, when I was but a novice at St. Prue’s, I served wine at a banquet our abbot gave in honor of Seraphina, herself a venerable lady of more than a hundred and ten. I had not yet discovered my historical vocation—in fact, I think something in her ignited my interests—but finding myself close to her at the end of the evening, I had the opportunity to ask exactly one question. Imagine, if you will, what question you would have asked. Alas, I was young and foolish, and I blurted out, “Is it true that you and Prince Lucian Kiggs, Heaven hold him, confessed your love for each other before the dragon civil war even began?”

Her dark eyes sparkled, and for a moment I felt I glimpsed a much younger woman inside the old. She took my plump young hand in her gnarled old one and squeezed it, saying, “Prince Lucian was the most honest and honorable man I have ever known, and that was a very long time ago.”

Thus was the opportunity of a lifetime squandered by callow, romantic youth. And yet I felt and still feel that her twinkling eyes answered, even if her tongue would not.

I have but skimmed events that other historians have spent entire careers untangling. To my mind, Seraphina’s story only really began when her uncle Orma, assisted by Undersecretary Eskar, went into hiding to escape the Censors, and when Seraphina, on the eve of war, decided the time had come to find the rest of the denizens of her mind’s garden, the other half-dragons scattered throughout the Southlands and Porphyry. Those are the events I will examine here.

I returned to myself.

I rubbed my eyes, forgetting that the left was bruised, and the pain snapped the world into focus. I was sitting on the splintery wooden floor of Uncle Orma’s office, deep in the library of St. Ida’s Music Conservatory, books piled around me like a nest of knowledge. A face looming above me resolved into Orma’s beaky nose, black eyes, spectacles, and beard; his expression showed more curiosity than concern.

I was eleven years old. Orma had been teaching me meditation for months, but I’d never been so deep inside my head before, nor felt so disoriented emerging from it.

He thrust a mug of water under my nose. I grasped it shakily and drank. I wasn’t thirsty, but any trace of kindness in my dragon uncle was a thing to encourage.

“Report, Seraphina,” he said, straightening himself and pushing up his spectacles. His voice held neither warmth nor impatience. Orma crossed the room in two strides and sat upon his desk, not bothering to clear the books off first.

I shifted on the hard floor. Providing me with a cushion would have required more empathy than a dragon—even in human form—could muster.

“It worked,” I said in a voice like an elderly frog’s. I gulped water and tried again. “I imagined a grove of fruit trees and pictured the little Porphyrian boy among them.”

Orma tented his long fingers in front of his gray doublet and stared at me. “And were you able to induce a true vision of him?”

“Yes. I took his hands in mine, and then …” It was difficult to describe the next bit, a sickening swirl that had felt as if my consciousness were being sucked down a drain. I was too weary to explain. “I saw him in Porphyry, playing near a temple, chasing a puppy—”

“No headache or nausea?” interrupted Orma, whose draconic heart could not be plied with puppies.

I shook my head to make sure. “None.”

“You exited the vision at will?” He might have been checking a list.

“I did.”

“You seized the vision rather than it seizing you?” Check. “Did you give a name to the boy’s symbolic representation in your head, the avatar?”

I felt the color rise in my cheeks, which was silly. Orma was incapable of laughing at me. “I named him Fruit Bat.”

Orma nodded gravely, as if this were the most solemn and fitting name ever devised. “What did you name the rest?”

We stared at each other. Somewhere in the library outside Orma’s office, a librarian monk was whistling off-key.

“W-was I supposed to have done the rest?” I said. “Shouldn’t we give it some time? If Fruit Bat stays in his special garden and doesn’t plague me with visions, we’ll be certain—”

“How did you get that black eye?” Orma said, his gaze hawkish.

I pursed my lips. He knew perfectly well: I’d been overtaken by a vision during yesterday’s music lesson, fallen out of my chair, and slammed my face against the corner of his desk.

At least I hadn’t smashed my oud, he’d said then.

“It is only a matter of time before a vision fells you in the street and you are run over by a carriage,” Orma said, leaning forward, elbows on his knees. “You don’t have the luxury of time, unless you plan to stay in bed for the foreseeable future.”

I carefully set the mug on the floor, away from his books. “I don’t like inviting them all into my head

at once,” I said. “Some of the beings I see are quite horrifying. It’s awful that they invade my mind without asking, but—”

“You misunderstand the mechanism,” said Orma mildly. “If these grotesques were invading your consciousness, our other meditation strategies would have kept them out. Your mind is responsible: it reaches out compulsively. The avatars you create will be a real, permanent connection to these beings, so your mind won’t have to lunge out clumsily anymore. If you want to see them, you need only reach inward.”

I couldn’t imagine wanting to visit any of these grotesques, ever. Suddenly it all seemed too much to bear. I’d started with my favorite, the friendliest one, and that had exhausted me. My eyes blurred again; I wiped the good one on my sleeve, ashamed to be leaking tears in front of my dragon uncle.

He watched me, his head cocked like a bird’s. “You are not helpless, Seraphina. You are … Why is helpful not the antonym of helpless?”

He seemed so genuinely befuddled by this question that I laughed in spite of myself. “But how do I proceed?” I said. “Fruit Bat was obvious: he’s always climbing trees. That dread swamp slug can loll in mud, I suppose, and I’ll put the wild man in a cave. But the rest? What kind of garden do I build to contain them?”

Orma scratched his false beard; it often seemed to irritate him. He said, “Do you know what’s wrong with your religion?”

I blinked at him, trying to parse the non sequitur.

“There’s no proper creation myth,” he said. “Your Saints appeared six, seven hundred years ago and kicked out the pagans—who had a perfectly serviceable myth involving the sun and a female aurochs, I might add. But for some reason your Saints didn’t bother with an origin story.” He cleaned his spectacles on the hem of his doublet. “Do you know the Porphyrian creation story?”

I stared at him pointedly. “My tutor woefully neglects Porphyrian theology.” He was my tutor these days.

Orma ignored the jibe. “It’s tolerably short. The twin gods, Necessity and Chance, walked among the stars. What needed to be, was; what might be, sometimes was.”