The Black Tower

Phlip Jose Farmer

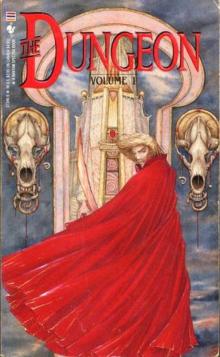

PHILIP JOSE FARMER'S THE DUNGEON, BOOK 1: THE BLACK TOWER

A Bantam Spectra Book / August 1988

Special thanks to Lou Aronica, Amy Stout, Shawna McCarthy, David M. Harris and Gwendolyn Smith.

Cover art and interior sketches by Robert Gould.

Cover design and logo by Alex Jay/Studio J.

The DUNGEON is a trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1988 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Cover art and interior sketches copyright © 1988 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc.

Foreword copyright © 1988 by Philip Jose Farmer.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information address: Bantam Books.

ISBN 0-553-27346-9

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Bantam Doubleday Del! Publishing Group, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words "Bantam Books" and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10103.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

· 0987654321

FOREWORD

". . . listen: there's a hell of a good universe next door; let's go."

So wrote the poet e. e. cummings in his "Pity This Busy Monster Manunkind."

He may not have been thinking of science-fiction and fantasy writers when he conceived these lines. But he certainly should have been. The writers in these genres most often set their stories in universes we do not know and never would—if these writers did not take us there. On the other hand, cummings may have been thinking that s-f (science-fiction) writers usually take us to other universes that are worse than ours—if that is, indeed, possible. In fact, they are more often than not universes that make ours look like a rest home. (But rest homes are often not such good places.)

The s-f writers play Virgil guiding his Dante (the readers) through various hells. That is, the universe next door is an Inferno. That's all right. We all want to go to heaven, but we do not want to read about it unless we're looking for a cure for insomnia. Nothing much happens in heaven, and most people there are bores. Hell is interesting and exciting. Things move fast and furious there, and the inhabitants don't know from one minute to the next if they'll be alive.

If that description of hell sounds like Earth, so be it. But our dangers are familiar, whereas those next-door are anything but ho-hum. We've never encountered them before, and we don't know just how to react because the environment is strange. And we run across, or into, entities, things, and situations outside our experience. In short, we are in the unmundane among busy monsters most unkind.

I am one of the writers who has, in many of my stories, put my heroes or heroines in the unmundane. And in such messes that even I did not know how they were going to get out of them when I hurled them into them. But I always figured out a way.

I also have used, in some of my works, characters and environments derived from the pulps. And I should add: derived from the spirit of the pulps, exotic adventure.

I have written many stories not connected with the above, but those that are have gotten much attention. Partly, perhaps, because they have become melded into one body. That is, they turn out to be living in one universe and are, indeed, related by blood. At the same time, pulp-originated though they are, they interact with, and are related genetically, to many characters of the classics. Thus, this universe next-door is a new one: pulp-and-classic. Farmerian.

This, plus my love of alien adventures, is why Byron Preiss asked me to edit and oversee the Dungeon series. This series is an emulation of the spirit, not the content, of the Farmerian universe next-door, the pulp-and-classic.

First, though, it's best to describe how and why I created this universe.

By the age of seven, 1925, I had read and was in love with the works of Mark Twain, Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, R. L. Stevenson's Treasure Island, Dickens's A Christmas Carol, the Oz books, London's Before Adam, H.G. Wells's and Jules Verne's works, Doyle's Holmes canon and The Lost World, and Burroughs's Tarzan and Mars series. I loved Homer's The Odyssey and the Norse, Greek, and American-native mythologies.

I was a bookworm yet was very athletic.

In 1929, when I came across the first issues of Hugo Gernsback's Science Wonder and Air Wonder with their wonderful Paul illustrations, life became even more golden. I plunged into the sapphire seas of the unmundane. I was an amphibian who alternated between the land of reality and the ocean of fantasy. But I much preferred the ocean. I still do, much to my detriment, because the land of reality is where we live most of the time.

Then I found the world of the pulps, the Argosy magazine, which came out weekly and carried many s-f and adventure stories. Later, I read all the many s-f magazines, and, in 1931, was captivated by the first The Shadow magazine. Money was scarce, though, during the Depression. When the first Doc Savage magazine came out in 1933, I had to choose whether to buy Shadow or Savage, and old Doc won out.

I also read Roy Rockwell's Bomba the Jungle Boy series and the s-f Great Marvel series. Though these were books, they certainly had the pulpish qualities. The stories were fast and gripped you until the end. The characters ranged from flat to caricature to a sometimes excellent portrayal. The writing was a spectrum of near-atrocious to competent to very good. The ideas were often stimulating and sometimes original, often banal, often secondary and derived but with new twists and facets.

In short, just like so-called "mainstream" literature, except that mainstream has no new or unusual concepts. If it does, it is not mainstream.

Of course, in those days I had no literary discrimination. They all read great to me, and many gave me some of the keenest pleasure I've ever had. I was in a Golden Age in my childhood and early youth. There were plenty of bad times, but, as I look back, the intimations of immortality, that blue-tinged, gold- shot thrilling and trembling-on-the-edge-of-revelation, that almost mystical feeling, came as much, perhaps more, from the pulps as from the classics I was reading.

Oh, yes, I forgot that The Arabian Nights and The Bible were early influences. There were so many that it's easy to forget some of them.

Later, I dived into the other works of Dickens and the non-Holmesian stories of Doyle, all of Jack London, and then Balzac, Rabelais, Goethe, Mann, Dostoyevsky, Joyce, Fielding, and the poets. When I was twenty, I found the biographies of Sir Richard Francis Burton and the books he had written. All read long before I began to sell my fiction to magazines.

The unconscious is the true democracy. All things, all people, are equal. Thus, in my mind, Odysseus towered no higher than Tarzan, King Arthur was no greater than Doc Savage, and Cthulhu and Conan loomed as large on my mind's horizon as Jehovah and Samson.

The pulps and the classics became fused in my mind. Lord Greystoke lived next door to Achilles and Natty Bumppo. Leopold Bloom met Lamont Cranston and Rudolf Rassendyll at cocktail parties. Milton's Lucifer had his horns polished at Patricia Savage's beauty salon, and She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed was pen pals with Scheherazade and Jane Eyre. Bellow Bill Williams (a series character in Argosy) bellied up to the same bar as Mr. Pickwick, the great god Thor, Falstaff, Old Man Coyote, and Operator #5. D'Artagnan, Thibaut Corday, Brigadier Gerard, and Lt. Darnot argued about military strategy over fine wines and snails. Joshua, Fu Manchu, Professor Moriarty, Captain Nemo, Pete the Brazen, and Doctor Nikola told tall tales aro

und a campfire. Paul Bunyan, Christian the Pilgrim, Hawk Carse, Don Quixote, and the Cowardly Lion argued about the metaphysical aspects of the Mad Tea Party.

You get the idea.

My conscious knows better, now, than to give these equal billing in the literary theater. But the Mother of Minds, the real She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed, my unconscious, knows no better.

I would be remiss if I did not tell how great an influence the early movies and the illustrations for the books of my childhood had on me. Before I could read, I saw (and still remember) Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood (1922). Fairbanks's The Black Pirate (1926) and, in 1925, Wallace Beery in The Lost World and Lon Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera thrilled and scared me. There were many more I have not forgotten and which still seethe in my unconscious.

The powerful illustrations by Dore in Pilgrim's Progress, Paradise Lost, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and Inferno and Wyeth's and Pyle's illustrations powerfully affected me. Paul's works for the Hugo Gernsback magazines sparkle in my mind like the massive jewels in the walls of ancient Opar.

These were, you might say, the visual equivalent of the classics and the pulps.

All: books, magazines, movies, and illustrations resonated on the same frequency. They no longer do so, but none of the magic is gone.

I have gone into such detail about the origin of the universe hight Farmerian because I want the reader to understand it. And it's a necessary prelude (from the Latin, meaning before the play and also, in a sense, foreplay).

It is necessary because this strange brew of the unreal and the real, the classics and the pulps, is what caused Byron Preiss, the producer of this projected' series, to launch it. The Dungeon works are based, in part, on the spirit that dwells in certain works of mine.

These works are also, in part, my tributes to other writers and, in part, derive from my childhood desire to continue the worlds of some of my favorite writers when they ceased writing them.

The works of mine noted below are, in my peculiar way (is there any other?), extensions and amplifications of the beloved fiction of my Golden Age:

The Opar series, based on the Tarzan and Allan Quatermain canons. (The wretched movies based on Haggard's character have no relation to Haggard's great novels.)

The Lord Grandrith-Doc Caliban series, based on Tarzan and Doc Savage. (But they give the darker side of these heroes.)

The Riverworld series, a fusion of my fascination with Burton, Twain and Dante and their philosophies and inspired ultimately by The Bible.

The World of Tiers series, inspired, in part, by the apocalyptic worlds of William Blake, the English poet; in part, by the American native culture-nero, Old Man Coyote; in part, by the exploits of d'Artagnan, Dumas's fictional character and also by the real d'Artagnan, of Rostand's stageplay hero, Cyrano de Bergerac and the real de Bergerac. (The latter also appears in the Riverworld series.) In part, by the wild tales of Thibaut Corday, Theodore Roscoe's French Legionnaire. In part, by Doyle's Brigadier Etienne Gerard, whom Doyle derived from the very real Napoleonic soldier, Baron de Marbot. (Marbot is also in the Riverworld series.)

The Adventure of the Three Madmen, in which Holmes and Watson encounter G-8, The Shadow, and Mowgli the Wolf-Boy, much to their consternation, and end in a lost country in Africa, the inhabitants of which are descended from the Zu-Vendi, Haggard's lost people in Allan Quatermain.

The Greatheart Silver series, one story of which is about a final showdown between the aged heroes and the decrepit villains of the pulps.

There are similar works of mine too numerous to mention. Enough said about them. But these have given rise to the novels of Dungeon, and these, as I said, emulate the spirit of the above. Universes begetting universes, not parallel to mine but asymptotic.

Richard Lupoff was wisely chosen to do the lead- off novel, The Black Tower. He is a man after my own heart, not with a knife, but in temperament. He's an authority on the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs and deeply read on the well-known and the obscure science-fiction and fantasy of the late 19th century and the early 20th century. He has written a number of parodies and pastiches of these. He is also the author of a series of parodies on science-fiction writers. I was one of his subjects, feebly disguised as Albert Payson Agricola, a hack s-f writer justifiably murdered. For those too young to know, Albert Payson Terhune was a very successful writer of dog stories featuring collies, one of which was named Lassie. Agricola is Latin for Farmer.

Lupoff's interest in the "old stuff" is not just a dilettante's. He's taken the early classics and not-so-classics of the pulps and popular books and reworked them. He has given them new life and new colors and new shapes in a thoroughly Lupoffian manner. However, despite often poking fun at these early s-f stories, often shot with ridiculous science, two- dimensional characters, and racism, he reveals a basic love for them. Though one part of him disbelieves them and is repulsed, to a certain extent, by their reactionary premises, another part really does believe in them and has great affection for them.

This is well. A writer who neither believes in nor loves the worlds he's writing about carries no conviction.

Like me, he is well acquainted with the 19th century. He knows that it is the mother of the 20th and that the Earth then still had its terrae incognitae. Africa was still the Dark Continent in a geographical and psychical sense.

And, like me, he used and uses real people among the fictional. The Black Tower starts on the Earth of 1878. Early on, we are introduced to some historical persons. A little later, we meet Sidi Bombay, a onetime gun-bearer for Sir Richard Francis Burton. And there is the fictional Quartermaster Sergeant Smythe.

His genius at disguises reminds us of The Spider, The Shadow, Doc Savage, and Sherlock Holmes. It also reminds me of Burton himself, a master of disguise.

In the spirit of my worlds, Lupoff writes a story in which things are seldom what they seem. The familiar and the cozy become sinister. The hero, as in so many of my works, is justifiably paranoid. Somewhere, somehow, somebody or something is pulling strings, and, willy-nilly, the puppets are dancing. But these puppets can think and can fight back.

Above all, Mystery reigns. It is not just the miasmic and misinterpreted atmosphere of detective stories and Gothics, though it is this, too. It's the mystery of the universe itself. Or, as in this case, also the mystery of another world.

One of Lupoff's additions to the universe, Neville Folliot's diary, with its update additions by an invisible hand, reminds me of Glinda the Good's great book. Events as they occur appear daily on the blank pages of her massive and magical volume. I doubt that Lupoff got the idea from the Oz books; it's no doubt his own concept. But it resonates from Oz, nevertheless.

Just as the spirit of both the pulps and the classics, a hybrid found only in our genre, resonates in his novels.

Both human and alien characters in The Black Tower are in the Farmerian spirit. I especially like Finnbogg, the bulldogoid, and Chang Guafe, the tortured and monstrous semishapeshifter. And there is the time nexus, where entities from everywhere and everytime are collected, a favorite situation of mine.

Collected by whom? For what purpose?

Ah, sweet and sour mystery!

When the series is done, we will see the universe as an organic whole. It will be explained in logical and believable terms.

But, as e. e. cummings wrote:

"—when skies are hanged and oceans drowned the single secret will still be man."

—Philip Jose Farmer

ONE

THE

ENGLISH

WORLD

CHAPTER 1

Piccadilly Circus

The curtain rang down on a jolly scene. The brothers James John Cox and John James Box celebrated their reunion. The audience, which had spent the evening in gales of laughter, now burst into storms of cheers and applause.

In their orchestra seats, Major Clive Folliot felt Miss Leighton's fingers close on his arm. Clive had been distracted by his thoughts during t

he performance, and he knew that Miss Leighton understood his feelings about his absent brother Neville—at least, she did so as well as anyone other than himself could understand those tempestuous feelings.

Is there anyone, other than a twin, who can understand the feelings of one twin for another?

"The play was jolly but it struck very close to home, did it not?" Annabella Leighton asked Clive Folliot. "It must have pained you, Clive."

Clive Folliot did not answer at once. It was necessary for him to compose himself. One did not give way to emotions in public, especially if one was an officer in Her Majesty's military service.

Clive was wearing the scarlet tunic and dark trousers of the Imperial Horse Guards. He brushed his reddish brown mustache with a hand that shook slightly. He turned toward Annabella and managed a grin. "Close to home, yes. But it was a fine entertainment nonetheless. I hope I did not ruin the performance for you, Miss Leighton."

As he spoke, he drank in her beauty with his eyes.

Annabella Leighton was a beautiful young woman— little more than a girl—some thirteen years younger than Clive Folliot's thirty-and-three. Her hair was a glossy jet black. For attendance at the theater it was done up in coils that glistened so that they seemed to pick up the cornflower blue of her darting, merry eyes.

Her shoulders were white and sweetly powdered, her bosom full and graceful and daringly revealed by her gown, when she permitted her shawl to slip from her shoulders. Her waist was slim, even tiny, albeit perhaps the least bit less so than it had been when she and Major Folliot had first become acquainted.

She smiled up at Major Folliot. "Oh, no," she said. "You could never ruin the performance for me. In your company, Clive, it could not have been other than enjoyable."

The theater was clearing around them as English gentlemen in evening dress or military uniforms and ladies in wide-skirted dresses slowly filed from their seats. A few Americans were scattered through the crowd, identifiable by their loud voices and swaggering way. They were coming back to England in growing numbers now. They had been, ever since the war between their states had ended—an event, Clive realized with a start, now three years past.