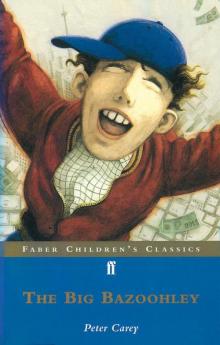

The Big Bazoohley

Peter Carey

PETER CAREY

The Big Bazoohley

illustrations by

Abira Ali

For Sam Carey and Charley Summers

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

EPILOGUE

Author biography

Copyright

ONE

LIKE MOST GROWN-UPS, Sam Kellow’s parents never guessed that their son ever thought about money. like most grown-ups, they thought he did not appreciate its value, and they both liked to say things to him like “Money doesn’t grow on trees” and “If you knew how much that cost, you wouldn’t do that.”

But in truth Sam knew a lot about how much things cost, and when the family arrived in Toronto in the middle of a blizzard, he knew they were there to sell his mother’s latest painting to the mysterious Mr. Edward St. John de Vere. He also knew they were down to their last fifty-three dollars and twenty cents.

Sam was only nine years old but he had a brain like a computer. He could add, subtract, do five-number long division in his head. He knew what sort of a hotel you could stay in for fifty-three dollars and twenty cents, and it certainly wasn’t a hotel like the one his father drove up to. The moment Sam saw the King Redward Hotel looming up through the snowstorm he got a very bad feeling in his stomach. When he saw the doorman, with all his gold buttons and medals on his big black coat, he knew this was a very expensive hotel and he felt even sicker.

What if his mother could not sell the painting she was carrying with her? What if the mysterious Mr. de Vere had died, or had been called away on business, or saw his mother’s new painting and didn’t like the faces on the people or the color of the sky?

They would be stuck in this hotel with a big bill and no money.

But even while Sam was worrying, his father was smiling and throwing his car keys to the doorman. His father was a gambler. In other words, he made all his money (or lost all his money) by guessing which horse would win a race, which playing card would turn up on the top of the deck, which drop of rain would run fastest down a windowpane. Money never bothered him, not ever. People said of Earl Kellow that he was the sort of man who would give you his last dollar, and although Sam was proud of his father, this also made him very nervous.

When they traveled to a strange city, Sam never knew whether they would be living on peanut butter sandwiches or sitting in a fancy restaurant being served that famous, fabulous, flaming ice-cream cake called Bombe Alaska.

He never knew whether they would stay in a palace or a fleapit, and in fact Sam knew plenty of both, and now that he was nine he knew which he liked better.

He watched his father tip the doorman five dollars and the bell captain two dollars, and when the porter brought their single suitcase to the room, Sam saw how much Earl Kellow gave him and he knew they now had only forty-four dollars and twenty cents left in all the world.

Sam looked at his mother to see if she was worried, and she looked down at him and smiled. He could not tell.

People were always telling Sam what a handsome woman his mother was, as if he never noticed himself. She was as tall as his father. She had big feet and hands and wild, curling blond hair and a pair of eyes which were different colors, the left bluish and the right brownish.

Her name was Vanessa and you might think—looking at those size-ten feet and those hands—that she would paint paintings as big as a dining-room table, but no—her paintings were no bigger than a matchbox.

No one ever explained how Vanessa Kellow could do it, how anyone could do it, and even if she had been two feet tall, you would have considered it a miracle. For these tiny paintings showed entire cities. Not just the buildings and the streets, but the bakers and butchers, and the stews bubbling in the pots, and the freckles on the faces, and the cat sleeping in the basket, and the fluff under the beds, although you could not see these things without a special magnifying glass, and then you might find a ruby ring in a secret drawer or a jar of blue-and-green-striped candy in a cupboard, and even then you would have the feeling that there were many things, things that were there, that you could not see.

People would go crazy when they saw his mother’s tiny paintings. They just had to own them, straightaway, and if they were rich people, they would pay a lot of money for the privilege. The only problem was, it took a whole year to do one little painting.

And it was one of these paintings, wrapped in tissue paper in her purse, that she was about to deliver. The minute they came into the hotel room, his mother set about fitting the painting inside a little box and then wrapping it in gold paper.

“Wow,” his father said, looking out the window of the hotel room. “Look at that city. Look at all that snow.”

His father loved new cities, new games, new people to gamble with. Sam did not understand why they couldn’t stay at home in Australia and just gamble there. Instead the family traveled the world, from race course to race course, from casino to casino, from Sydney to Paris to Tokyo to London to Toronto, seeking what his father called the Big Bazoohley, which meant the Big Win, the Big Prize, the Jackpot.

Sometimes he got the Big Bazoohley and sometimes he did not, but in any case he was tall and handsome and fun to be with, even when he lost. He could balance a dining chair on his nose and find pennies behind your ears. He had bright blue eyes and he could play cricket and baseball, and wherever they traveled there was something about him that made people like him and lend him money when he had none of his own.

Sam stood beside his father and watched the snow come down. The flakes were huge, and the fall was dense. The snow blew in swirls and eddies. It stuck to the window ledge and filled the ledge, and as they watched, it began to creep up the glass as if it meant to pull a soft white blanket over the face of the hotel.

“Gee, it’s beautiful,” his father said. Sam would have agreed if he knew that they could stay inside where it was warm and safe, but he couldn’t look out the window. He looked instead at the expensive gold-framed mirrors, at the big sunken bath, at the forty-eight-inch TV, at the perfect green grapes in the glistening silver bowl.

“How will Mum get to her appointment?” he asked his father. “Maybe she won’t be able to get there in all of this snow.”

“This is Toronto,” his father said. “This is a great city in the snow. They have a wonderful subway system. They have shopping centers underground. And as a matter of fact, Mr. de Vere has a mansion which is totally underground. You reach it from a door on the Bloor Street subway platform.”

Sam was too worried about his mother to think it strange that a rich man would have his front door on a subway platform. He looked out the window. The snow was falling so fast now. It lay itself on the roofs below and all the streets and made everything soft and curved and white and quiet. In all that great city nothing was moving but the flashing yellow lights on the top of the snowplows.

“But how will she get to the subway?”

“I’ll take the hotel elevator,” his mother said. She stood in the middle of the room with the tiny gold-wrapped painting held in the palm of her hand. “The Bloor and Yonge lines run through the hotel basement. Neat, huh?”

“Neat,” said Sam, but when his father wanted him to go out and sled and play in the snow, he said he would rather stay in the room, and so, when his mother left, Sam and his dad sta

yed in the room and they watched the cartoon channel and after a while Sam stood and went to the door, where he tried to see, without being obvious, how much this hotel room was costing.

Four hundred and fifty-three dollars a night. Plus tax.

TWO

SAM’S MOTHER DID NOT get back until it was dark, and when she came into the hotel room, she had a funny look on her face.

“So?” his father said. He walked toward his wife with his arms wide. “Do we celebrate now or later? Do we order the Bombe Alaska? Do we put on our dancing shoes, or what?”

“Excuse me,” Vanessa said, and she ducked sideways into the bathroom, where Sam could hear her blowing her nose. When she finally came out, she still had a funny look on her face.

Sam got a bad feeling in his stomach. He lay on the big king-size bed with the carved gold headboard and pretended to watch the television.

His mother sat down on the sofa beside his father.

“So?” Earl Kellow asked quietly.

“De Vere wasn’t there,” his mother said.

Sam saw his father’s shoulders shrug. He’ll come back.”

“It wasn’t there,” his mother whispered. “Nothing was there. The entrance to the mansion wasn’t there anymore.”

Sam saw his father take his mother’s hand and begin to stroke it. He said something Sam could not hear.

“Earl” Vanessa said. “I’ve been there five times before. I know the station. I know the entrance.”

“It’s the door that says ‘Cleaning 201.’” He turned to Sam. “Crazy old de Vere,” he said. “Richest man in Toronto and he writes ‘Cleaning 201’ on his front door.”

“Earl,” Vanessa said, “I know what it says. The sign wasn’t there. The door wasn’t there. What I’m trying to tell you is—the whole station has been rebuilt.”

“Maybe you got out at Wellesley instead. Or Dundas.”

Vanessa whispered something short and sharp in her husband’s ear.

“Okay,” Earl said, “maybe I will.”

“Suit yourself,” Vanessa said.

“Sam,” his father said, “will you go down and wait for me in the lobby? I just want to talk to Mummy for two minutes.”

“Sure,” Sam said, but he could see his father was worried, and that made him feel really bad.

So Sam went down in the elevator to the lobby and sat in a deep upholstered chair beside a fountain. The lobby was tall and grand with sparkling chandeliers and Oriental rugs. Grown-ups in big fur coats came in the front door laughing and talking excitedly while the snow melted on their soft black hats. A porter in a uniform walked past holding a huge blue-and-yellow parrot in a gold cage. A girl of six with very white skin and a long silver ball gown was speaking seriously to an older boy, a sixth grader at least, dressed in a black tuxedo.

As they walked past Sam, he heard the boy say excitedly, “He’s sick? He’s really sick?”

And the girl giggled behind her hand and said, “Ten thousand dollars says he is.”

Sam wished he had ten thousand dollars.

Then his father arrived and silently he held out his hand. Sam did not ask what his mother and father had talked about. He stood and walked hand in hand with his father across the lobby. They passed six cashiers, all standing in a line behind a shining mahogany desk. The cashiers wore black suit jackets and had black slicked-back hair. Sam felt that they could tell that Sam and his dad did not have the money to pay the bill.

Just beyond the cashiers there was another elevator, which went to the parking lots and the King Street subway station.

When they stepped out of the elevator, there was a token booth.

“I don’t have to pay,” Sam whispered. “I can duck under.”

“You can do no such thing,” his father said.

“Why not?”

“Because it’s cheating.”

When they pushed through the turnstile, they had forty-one dollars and seventy cents left.

Two minutes later the train arrived. Sam, who had spent the week before in New York City, was surprised by how clean and quiet it was. Five minutes later they arrived at Bloor Street.

Sam’s father led the way along the northbound platform.

“You said there was a whole house in there? In the subway?”

“You wait till we find him. He looks kind of like a mole.”

“He has tunnels?”

“He has a mansion under here. There’s a marble fountain just inside the door. There is a ballroom, and galleries with paintings worth millions of dollars.”

“But why does Mr. de Vere live here?”

“When you’re very rich,” his father said, “you can live any way or anywhere you like. Eddie de Vere is a funny little mole of a guy, not much taller than you are. He is a very big gambler, but he’s also very shy, and he doesn’t want people to know he is rich. He walks around the street in old overalls carrying a plastic bucket and then comes down to the subway and opens the door marked CLEANING 201. He likes secrets. That’s why he loves your Mum’s paintings. There’s so much more in them than you think when you first glance at them.”

“Like him?”

“I guess,” his father said. “But who knows what he thinks.” He was standing in front of an advertisement for M&M’s, running his hands over the picture. “This is very strange …” he said. His voice trailed off. He was frowning.

“So?” Sam asked. He had never seen his father look so worried before.

“I’m darned if I know,” his father said. He put the tips of his fingers behind the sign and pulled at it. “The door used to be here, but it’s not here now.” He paused and rubbed his ear. “They’ve been rebuilding….”

“It can’t be just gone,” said Sam, looking at the big bright M&M’s in front of him.

“Sam, I’m telling you, they’ve rebuilt the station. They’ve blocked up the doorway.”

“They’ve put the doorway someplace else.”

“Yes, I guess they have.” Sam’s father looked up and down the bright shining white-tiled wall. There was not another door in sight.

“Maybe he’s in there still,” Sam said. “Maybe he’s on the other side of the wall. Maybe he would hear us if we knocked the right way. Maybe there’s a code. Maybe we should push on one of these M&M’s.”

His father shrugged.

Sam smacked the picture of the M&M’s with his hands.

“So what will happen to us?” Sam said. He began to cry. It was all too much. “What will happen to us now? Where will we get our money? How will we pay for the hotel?”

“Well,” his father said, “I’ll tell you what …”

And he picked Sam up and held him in the air, and Sam looked at his father’s face and saw how he smiled and how calm he was.

“I’ll tell you what,” his father said, hugging him.

“What?” Sam was smiling, too. He could see his father knew just what to do.

“One thing I’ve found out in life is one door shuts, another door opens.”

He put Sam down.

“Which door opens?” Sam said. “Where?”

But his father shrugged and held out his hand. “Come on,” he said. “Let’s go back and see your mum.”

But Sam didn’t move. He looked into his father’s eyes and saw Earl Kellow did not know what to do.

“You’re lying!” he yelled. “You don’t know anything. You’re lying. You don’t know what to do.”

His father tried to hug him, but Sam was angry and would not let him.

Finally he took his father’s hand and walked with him up and down the platforms, looking for the door marked CLEANING 201. As they walked the busy corridors of the Queen Street station, Sam was still angry and upset and it never occurred to him that what his father had said might actually come true.

Before midnight another door would open. And Sam would walk right through it.

THREE

SAM, WAS SURPRISED, when they got off the train, to find the

y were at a station called Osgoode.

When they went up in the elevator, he found, not a hotel lobby with chandeliers, but a huge supermarket. When he saw the supermarket, Sam’s heart fell. He knew what they were buying—peanut butter, bread, milk. That’s how he knew his father was defeated. It was what he always bought when he had no money.

His father spent six dollars and ten cents at the supermarket. Which meant he had thirty-five dollars and sixty cents to pay for the hotel bill. And yet Earl Kellow didn’t seem to worry, and when he spent another two fifty on two tokens to get back to the hotel, he was whistling. Back in the hotel the lobby looked even grander than it had before. There was a famous film star checking in. There was a pretty fifth grader in a ballerina gown with a diamond tiara in her hair. She looked beautiful, like a real-life princess. She looked at Sam and smiled, but Sam—instead of smiling back—frowned and shifted his supermarket bag so she wouldn’t see the peanut butter showing through the plastic.

As he walked across the marble floor, he imagined everyone was looking at his pathetic little bag of groceries—cashiers, bellboys, a pair of twin boys in identical brown velvet suits and neat bow ties.

“There’s a lot of very rich people staying here,” he whispered to his father.

“These kids?” His father laughed. “They’re pretending to be like the kids in those shampoo commercials. Did you see the sign?”

Sam looked at the banner which was now draped across the high ceiling of the lobby. It read: THE KING REDWARD HOTEL WELCOMES FINALISTS IN THE PERFECTO SHAMPOO “PERFECTO KIDDO” COMPETITION.

“Perfecto Kiddo,” Sam said. “It’s not even English. It doesn’t make sense.”

“Why would it make sense, kiddo?” Earl Kellow grinned. “It’s a nonsensical situation. It’s a whole lot of crazy parents trying to make money from their children.”