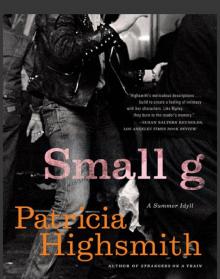

Small G: A Summer Idyll

Patricia Highsmith

ADDITIONAL BOOKS BY PATRICIA HIGHSMITH

PUBLISHED BY W. W. NORTON

Strangers on a Train

The Price of Salt (as Claire Morgan)

The Blunderer

The Talented Mr. Ripley

Deep Water

This Sweet Sickness

The Glass Cell

A Suspension of Mercy

Ripley Under Ground

A Dog’s Ransom

Ripley’s Game

Little Tales of Misogyny

The Animal-Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind

The Boy Who Followed Ripley

The Black House

People Who Knock on the Door

Mermaids on the Golf Course

Ripley Under Water

Nothing That Meets the Eye: The Uncollected Stories of Patricia Highsmith

ADDITIONAL TITLES FROM OTHER PUBLISHERS

Miranda the Panda Is on the Veranda (with Doris Sanders)

A Game for the Living

The Cry of the Owl

The Two Faces of January

Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction

Those Who Walk Away

The Tremor of Forgery

The Snail-Watcher and Other Stories

Edith’s Diary

Found in the Street

Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes

Small g:

A Summer Idyll

Patricia Highsmith

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

To my friend Frieda Sommer

Contents

Begin Reading

1

A young man named Peter Ritter came out of a cinema in Zurich one Wednesday evening around midnight. It was January, cold, and he hurried to fasten his thigh-length leather jacket as he walked. Peter was heading for home, where he lived with his parents, and he had decided to ring Rickie from there rather than from a bar-café. Peter took an alley that was a shortcut. He was buckling the jacket belt, when a figure leapt out of the darkness on his left and said, “Hey! Give us your money!”

Peter saw a knife in the fellow’s raised right hand, a longish hunting knife.

“OK, I’ve got about thirty francs!” Peter said, standing tense, fists at the ready. Sometimes drug addicts could be scared off, easily. “You want that?”

A second fellow had sprung up on Peter’s right.

“Thirty with that jacket!” mumbled the man with the knife, and struck—a hard stab under Peter’s ribs on his left side.

Peter knew the knife had gone through the leather. He was reaching under the jacket for the wallet in the back pocket of his jeans. “OK, I’m getting—”

The second man gave a funny shrill laugh and stabbed Peter in his right side. Peter staggered, but he had the wallet out.

The man on the left snatched it. More laughter, and a blow to Peter’s throat now—not a fist, but another stab.

“Hey!” Peter yelled, twisting, in pain and thoroughly scared. “Help! Help me!” Peter hit the man on his left with his fist, fast as a reflexive gesture.

The second man bumped Peter, sending him toward the blackness of the house walls, where Peter hit his head. Trotting footsteps faded.

Peter was aware of lying on the worn stones of the alley, of gasping. Blood was choking him. He drank blood in order to breathe. Got to ring Rickie, as he’d promised. Rickie was working late tonight, as he often did, but Rickie would be expecting . . .

“Here! Look, here he is!”

Other people.

“Hey! Where’re you hurt?”

“No, don’t move him! Shine the light here!”

“That’s blood!”

“. . . ambulance?”

“Beni went to phone.”

“. . . young guy . . .”

“Is he bleeding! Wow!”

Peter felt as if he were going under an anesthetic, unable to speak, getting sleepier, though his neck was beginning to hurt. He tried to cough and failed, inhaled, gasped, choking and unable to cough.

Less than an hour later, someone had found Peter’s discarded wallet in the same alley, and turned it in to the police. Peter Ritter of such-and-such address. The police notified his mother that Peter had been dead on arrival at the hospital. An intern had heard him say “Rickie.” Did that name mean anything to her? Yes, she said. A friend of her son’s. He had just telephoned her. She gave Rickie’s address, on their insistence. Then the police came to escort Frau Ritter to the morgue.

That same night the police visited Rickie Markwalder, who was working in his studio. He was aghast at the news, or so he seemed to the police. He had been expecting a telephone call from Petey around midnight. Rickie wanted to speak with Petey’s mother, but the police suggested tomorrow, because Frau Ritter had been given sedative pills tonight to take before trying to sleep. Her husband was away on business just now, the police said, a fact which Rickie knew.

Rickie telephoned Frau Ritter the next day, having waited until nearly noon. “I am absolutely shattered,” Rickie said in his simple, almost clumsy way. “If you would like to see me, I am here. Or I can come to you.”

“I don’t know. Thank you. My brother is here.”

“Good. The funeral—shall I phone you tomorrow?”

“It’s—a cremation. Our family way,” replied Frau Ritter. “I will let you know, Rickie.”

“Thank you, Frau Ritter.”

As it turned out, she didn’t let him know, but that could have been an oversight, Rickie thought. Or she might not have wanted him present with the relatives, the cousins, at the service which Rickie read about in the Tages-Anzeiger. He sent flowers to Petey’s parents, anyway, with a card stating his “deepest sympathy,” words that had become trite, Rickie knew, but were in his breast sincere.

Luisa would be shocked. Did she know already? The item in the Tages-Anzeiger had been short, and Rickie had found it only because he had looked for it. He preferred to keep out of the way in regard to Luisa and Peter, and he had the feeling Luisa didn’t much like him, Rickie. Why should she? Luisa had been in love with Petey, maybe an adolescent crush, lasting a couple of months, but still—Rickie decided not to say anything to Luisa. He realized he was assuming she was over her attraction to Petey, because he wanted to assume that. It was easier than telling her in Jakob’s, where Luisa was always in the presence of Renate something, her boss, and boss of a few other young apprentice seamstresses, who worked in Renate’s atelier.

2

Rickie Markwalder, led by Lulu on her lead, clumped along his street en route to Jakob’s Bierstube-Restaurant. This was known as the Small g at weekends, but that name wasn’t appropriate around 9:30 A.M. on any day. One of the guidebooks on Zurich’s attractions so categorized Jakob’s—with a “small g”—meaning a partially gay clientele but not entirely.

“Come on, Lulu! Oh, all right,” Rickie murmured tolerantly as the slender white dog circled purposefully and crouched. Rickie urged her gently into the gutter with the lead, then pushed his hands into the sagging and slightly soiled pockets of his white cardigan. Lovely day, he was thinking, summer getting into its full glory, the pale-green leaves on the trees brighter and bigger every day. And no Petey. Rickie blinked, feeling again that shock and sudden emptiness. Lulu jumped onto pavement level, scratched with her hind feet, and strained toward Jakob’s with renewed zeal.

Aged twenty, Petey had been, Rickie thou

ght bitterly, and for no reason swung his leg and kicked an empty milk container off the pavement into the gutter. Here he was, forty-six—forty-six—still going strong (except for his own abdominal stab wound, ugly, and which he had allowed to bulge a little), while Petey, such a beautiful image of—

“Hey! Kicking refuse into the street? Why don’t you pick it up—like a decent Swiss?” A dumpy woman in her fifties glared at Rickie.

Rickie made a turn to go back for the container—a little half-liter one, anyway—but the woman had darted and picked it up. “Maybe I’m not a decent Swiss!”

The woman’s face twitched in contempt, and she went off with the milk container in the opposite direction from Rickie’s. His wide mouth lifted at one corner. Well, he wasn’t going to let that ruin his day. Most unusual, he had to admit, to see an empty container of any kind in a Swiss street. Maybe that was why he’d felt inspired to kick it.

Lulu made a sharp right and drew Rickie through the front gate of Jakob’s, past the terrace tables and chairs which now were unoccupied, because it was a bit chilly for outdoors breakfasting.

“’Allo, Rickie. And Lulu!” This from Ursie in the doorway, wiping her hands on her apron, bending to touch Lulu who raised herself a little and flicked her tongue at Ursie’s hand, missing it.

“Good morning, Ursie, and how are you this fine morning?” asked Rickie in Schwyzerdütsch.

“Well as ever, thank you! The usual?”

“Indeed, yes,” replied Rickie, slowly making for his left corner table. “Hello, Stefan! How goes it?” This to a one-eyed man, a retired postman, about to dunk a roll into his cappuccino.

“I see the world with a unique optimism,” Stefan replied, as he replied half the time. “Hello, Lulu!”

Rickie took a Tages-Anzeiger from the circular rack and seated himself. Dull news, rather the same as last week and the weeks before, little formerly Russian states he had barely heard of, all near Turkey, it seemed, were squabbling and killing their inhabitants, people were starving, their houses blown up. Of course some lives—like these—were sadder than his own. Rickie had always known that and admitted it. It was just that, when tragedy struck, why not say it hurt? Why not say it was important, at least for the individual?

“Danke, Andreas,” said Rickie with a glance up at the dark-haired young man who was setting down his cappuccino and croissant.

“’Morning, Rickie. ’Morning, Lulu.” Andreas, sometimes called Andy, bent and gave a mock kiss to Lulu, who had seated herself on a straight chair opposite Rickie. “Would Madame Lulu like something?”

“Woof!” Lulu replied, every bit of her signifying a “Yes!”

Andreas straightened up and laughed, swung the empty tray between his fingertips.

“She’ll have a taste of croissant from me,” Rickie said.

Rickie returned to his paper. With croissant sticking out of his mouth, Rickie used both hands to turn the pages to “Recent Events.” This was a short column with usually four or five items: a woman had had her handbag snatched; a youth not yet identified found dead from an overdose under a park bench in Zurich. Today an item was about a man aged seventy-two who had been hit over the head and robbed in a village Rickie had never heard of near Einsiedeln.

Ah well, seventy-two, Rickie thought, was getting on, and such a man couldn’t be expected to put up much of a fight. But he’d come out of it alive, it seemed. Taken to hospital for shock, said the newspaper. Now Petey, in Zurich, had put up a fight (according to a witness), as many a young man would, and Petey had been in top form. Rickie made himself loosen his tight grip on the newspaper.

“Here, my angel.” Rickie reached across the table and extended a crunchy morsel.

Lulu’s pink tongue took care of the morsel, losing not a crumb, and she gave a tiny whine of pleasure.

At that moment, a smallish female figure in gray came in, cast a swift glance around, and made for a table against a wall opposite and to the left. Opposite meant quite far away, because Jakob’s was a large establishment.

Jakob’s Biergarten was three or four stories high, but nobody thought about the upper stories. The ground floor, walls and ceiling were of old dark wood, like the benches and tables and one later-made semipartition which was already old enough to blend with the rest. No formica, no chrome. The mirror behind the bar looked in need of a washing, but so many cards and sentimentalia were stuck all round its frame, it would have taken a courageous person to tackle it. The rather low ceilings had thick square rafters that looked even darker than the benches and booths, as if centuries of smoke and dust had become part of the wood. If Rickie was lonely, he came here for a beer, and if he tired of his own cooking, Ursie always had sausage and potato salad or sauerkraut till midnight.

The woman in gray was Renate something-or-other, and he disliked her. She was at least fifty, always neatly attired and in curiously old-fashioned style. Though she was polite and left a tip sometimes (Rickie had seen it), few people liked Renate. She was somehow a spy, hostile, spying on all of them at Jakob’s, contemptuous of all of them despite her smile, yet so often here, nearly always at this time, for her mid-morning coffee. Rickie was sure Renate got up early and wanted her girls at work before eight. From where he sat, Rickie could just make out little gray-tasseled scallops on the sleeves (somewhat puffed) of Renate’s flower-patterned dress, tassels midway down the skirt, too, and of course at the hem. Practically Alice in Wonderland! A long dress it was, to hide as much as possible Renate’s club foot, or whatever they called it these days. She wore high shoes with one sole thicker than the other. No doubt this had tended her toward the Edwardian gear. Rickie imagined her a tyrant with her young female employees. Now Renate inserted a cigarette into a long black holder, lit it, and focused a small automatic smile at Andy as she gave her order.

Rickie glanced at his watch—nine fifty-one. His helper Mathilde was never at his studio before ten-ten, even though when he had hired her, Rickie had asked her please to come by ten. Rickie knew he was not good at being forceful with people. Curiously, he was tougher in business deals, he thought, and this gave him consolation.

“Appenzeller now, Herr Rickie? Oder—” Or another cappuccino, Andreas meant.

“Appenzeller, ja, danke, Andy.”

Rickie lifted his eyes from his newspaper as another voice said, “’Morning, Rickie!”

This was Claus Bruder, who had appeared from round the partition behind Rickie.

“Well, Claus! Still ogling your female clients?” Rickie smiled. Claus was a bank clerk.

Claus wriggled and replied, “Ya-aes. Hello, Lulu—gut’n Morgen! I was wondering, can I borrow Lulu for this evening? Quiet evening. Bring her back here tomorrow round this time?”

Rickie sighed. “All night? Lulu was out late last night. Someone had her out till two. She needs her sleep. Is it so important?”

“Here in Aussersihl. I have a new date tonight.”

Lulu was a plus, that was all, even though any honest borrower would have to admit to anyone that he didn’t own Lulu. “No,” Rickie said with difficulty. “The guy will like you just the same with or without Lulu. You know? C’est la vie.”

Claus, younger by nearly twenty years than Rickie, had no reply or decided to hold his tongue, and looked wistfully at Lulu. “But, sweetie, you bring me luck!”

Lulu responded with an “Ooof!” and extended a paw toward Claus’s outstretched hand. They shook.

“See you, Rickie! Have a nice day,” he added in English, a semi-insulting thing to say.

“And up yours!” Rickie replied genially. He picked up his Appenzeller. The first sip tasted as if it were something he needed, its sweetness blended with the bitter cappuccino on his tongue. He might have put Renate out of his mind with a cigarette and a return to the newspaper, but Luisa had arrived to join Renate, and Rickie’s eyes were hel

d. She was so young and fresh! Now Luisa was smiling at Renate, taking a seat on the bench. Luisa had been in love with Petey—yes, really in love, Rickie knew from what Petey had told him. Petey had been a little troubled by it, polite, not knowing how to handle it—handle Luisa’s loving gazes. And how jealous the old witch Renate had been, and had shown herself to be! Fairly audible lectures to Luisa right here in Jakob’s! There had also been “asides” to others, Renate on her feet, flouncing her long skirt and turning like a flamenco dancer as she announced, “It’s wahnsinnig for a girl to get a crush on a homo! These perverts are in love with their looking-glasses! With themselves!” Renate had got little support from the habitués of Jakob’s, quite a few of whom were gay and the rest at least rather sympa. But that hadn’t stopped her. Oh no!

And it was horrid, had been, Rickie remembered, to see how Renate fairly gloated in triumph over Luisa’s tears (alas, a few had been shed in public here) when it became apparent that Petey was not going to respond to Luisa’s declaration of love. Poor Petey had been embarrassed, and Rickie had urged Petey to bring Luisa some flowers and he had, at least once, Rickie remembered, encouraged the boy to be understanding. What did that cost? Nothing. And you’ll be a better Mensch for it, Rickie had said. True. Rickie drew gently on his cigarette and tried to cool his ire. The day was just beginning.

“Rickie—and Lulu!” said a female voice.

Rickie looked up. “Evelyn! So! How are you, my lovely? Want to sit down?”

An empty wooden chair stood beside the one Lulu occupied.

“No, thank you, Rickie, I’m already a little late for work. This drawing—”

Rickie watched her open a large manila envelope on the table, and pull out a pen-and-ink drawing on heavy paper, a castle with spires in the sky, a visible moat among the bushes and trees at the bottom. “Pretty!”

“The kids love it. Well, it is well done. It’s by a boy about thirteen and I think good for that age. Could you—”

“Copies,” Rickie filled in. “Yes.”