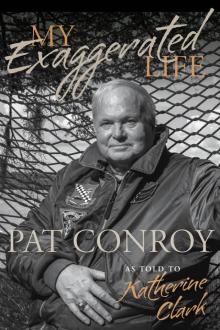

My Exaggerated Life

Pat Conroy

My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life

Pat Conroy

As Told to

Katherine Clark

THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA PRESS

Publication is made possible in part by the generous support of the University Libraries, University of South Carolina.

© 2018 Katherine Clark

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-907-1 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-908-8 (ebook)

Front cover photograph © Jim Herrington

This book is dedicated

to the memory of

PAT CONROY,

whose friendship changed my life.

Contents

Introduction

Prologue

1 Beaufort, South Carolina: 1967–1973

2 Atlanta: 1973–1981

3 Rome/Atlanta/Rome: 1981–1988

4 Atlanta/San Francisco: 1988–1992

5 Fripp Island/Beaufort, South Carolina: 1992–2016

Epilogue: Beaufort, South Carolina

Postscript

Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

Introduction

A story untold could be the one that kills you.

PAT CONROY, Beach Music

Pat Conroy is a famous, best-selling, beloved American author who has won a place in the hearts of millions of readers with his books The Great Santini, The Lords of Discipline, and The Prince of Tides, among many others. Pat Conroy was also an American original: a military brat, an adopted son of the Carolina lowcountry, a starting point guard for a Division I college basketball team, a self-made writer, a champion of the underdog, and a friend of little people. Many know and love this man’s work, but most will not have had an opportunity to get to know the inimitable man himself. The purpose of this book is to capture Pat Conroy in full measure, so that readers who never met this singular American character will have their chance to encounter him in these pages and experience something of what it was like to hear his stories in person, as only he could tell them.

Conroy’s readers will already know a great deal about the author’s life from his autobiographical fiction and nonfiction. We will learn a good deal more from the inevitable scholarly biographies that will follow in due time. This book does not attempt to supplant or compete with an academic rendering of Conroy’s life and in fact strives to avoid too much overlap with well-known Conroy lore and previously published material. When a major subject of Conroy’s life—like his mother’s death, for example—receives scant attention in these pages, that’s either because Conroy has written extensively on this subject in other works, or because he was not interested in addressing it here. What this book seeks is not to offer a comprehensive accounting of the author’s life, but to preserve the voice, the character, the personality, and the humanity of Pat Conroy in the amber of his own spoken words.

To that end, no one actually wrote this book. I interviewed Pat Conroy for about two hundred hours and edited the transcripts of our recordings into a narrative that hews as closely as possible to the tone and spirit of Conroy’s words. My job was to select and structure the text on the page, but what’s on the page is Conroy speaking. Here Conroy is the narrator of his life, not the scholar of it. It was not my job to be the scholar of his life here either; that enterprise is for a different book. My role was simply to be an editor who enabled Conroy to be Conroy. And when Conroy is being Conroy, I find him an extremely reliable and credible narrator, but the fact remains that the narrative here is his life as he remembers it and chooses to tell it. On the one hand, I am certain that Pat made a disciplined effort to be as accurate and honest with me as he could be. On the other hand, I am equally certain that some of the stories he told me reflect how a writer’s imagination takes hold of real events and makes them better in the telling over years of retelling.

In editing our transcripts, my philosophy was to let Pat be Pat on the page as he was in our interviews, because this kind of book should provide a warts-and-all portrait of a character, along with the gaffes and all narrative of his life, as straight from the horse’s mouth as feasible. My responsibility is to share what he told me, because this represents what readers would have heard for themselves if they had met Pat at Griffin Market or sat with him on his balcony as he told stories. And this is the purpose of the book. Instead of hewing literally to any factual record, an oral biography is designed to convey many other kinds of truths about character and voice. What’s in these pages offers a glimpse into Pat Conroy’s psyche and the emotional reality he lived with from day to day, year to year.

Here is Pat’s philosophy on the subject of his own nonfiction, including the interviews we recorded for this book: “In memoir, you better make sure you’re dealing with the truth as best you can tell it, as best you can carve it out, as best you can remember it. The problem is, once it’s in a book, it’s going to sound like the whole truth, and it’s not going to be. It’s the truth as best I can put it together. But it’s not going to be the whole truth, because everybody’s version of what happened is a little different; and it’s not going to be the literal truth because I don’t have a recording of my life.” He also noted: “My answers can change on a daily basis. I can say something portentous as though I’m giving the final benediction on something, and then I will say something completely different the very next day.”

Memoirist and novelist, Pat Conroy was also a raconteur who delighted audiences as well as friends and family with his storytelling. Not every writer is a great raconteur, just as not every raconteur has the ability to be a good writer. In fact the first oral biography on which I collaborated came into being because the black midwife Onnie Lee Logan did not know how to write. On the other hand, she was a great storyteller out of the oral tradition of the African American South, in which knowledge and information are stored and passed down through stories told and repeated over generations. The Capote-esque bon vivant Eugene Walter of the second oral biography I worked on was a good writer who produced a few novels and poems, but these did not come close to his brilliance as a raconteur whose stories captured the brilliance of a uniquely well-lived life.

Likewise, great writers are often not great talkers. William Faulkner, for example, was notorious for being taciturn in public and speaking only in monosyllables. He preferred to listen and observe, especially when others were doing the storytelling on the front porch of the general store or at the hunting lodge where he was a regular guest. He internalized the stories told by the raconteurs in his family and community and later spun them into literary gold, but he himself was much more writer than raconteur.

Pat Conroy was one of those rare beings whose gift with the spontaneous spoken word equaled his skill at crafting the written word. However it is not Conroy’s celebrity as an author that makes him a great subject for an oral biography. In fact I prefer unknowns as subjects and was initially leery of any project involving a famous person. The first two subjects of the earlier oral biographies I worked on had both done great things with their lives against huge odds, but not to the point that the world knew who they were or what they’d done. This anonymity did not bother either of them or detract from their own sense of personal success. Both individuals had a strong sense of identity that empowered them to pursue lives of great meaning and fulfillment. One lesson of these lives is that the inner conviction of being “somebody” is more important than the celebrity bestowed by public o

pinion or acclaim. Then, through the act of narrating their life stories, both these “nobodies” showed the world what it means to be somebody.

Although Conroy believed he was destined to remain a nonentity, he became famous before he was thirty when his book about teaching black students on a Gullah sea island was adapted into a movie in which the handsome Hollywood star Jon Voight played the role of Pat Conroy, or Conrack. This was the beginning of a string of books and then movies based on the books, which all added to his renown. In the midst of increasing fame and success, Pat lived an outsized life, full of well-publicized conflict and drama. He loomed larger than life in the public imagination as a heroic figure who achieved mythic proportion even before he died.

But in contrast to those “nobodies” who knew they were really somebody, Pat Conroy was a somebody who could never get over the feeling that he was nobody but “that beaten kid and the boy who could not defend his mother.” He was haunted by the fear that life would eventually punish him and make him suffer for the way the world had mistakenly crowned him a personage. Ironically in this case, it was Conroy’s insistence that he was a nobody like all mere mortals that makes him a great subject for oral biography. Although he may have been a legend in his own time, he was not a legend in his own mind. Pat Conroy saw himself as a flawed human being who was blessed with great good luck in his professional career and cursed with self-inflicted wounds in his personal life. To the extent this book conveys Pat’s own image of himself, it will demythologize that mythic figure of the public imagination. For him this project was not about myth making, but about truth telling. This is not to say that some of his stories don’t contain mythologized elements that have accrued over years of retellings. It’s to say that Pat’s mission here was not to build his legacy, but to bare his soul. In our interviews he could not have been less concerned with burnishing his legend, polishing his image, or trumpeting his masculinity. The great charm and power of his character is this ability to reveal himself utterly in naked humanity. Just as he advised other authors to do in their writing, Pat went deeper and deeper into himself in our talks. At one point he told me he had not gone as deeply into himself since he’d last been in therapy with his psychologist, Marion O’Neill, whom he credits with saving his life. As our interviews came to an end, he observed, “I have blurted out my entire life to you nakedly and unashamedly when I should have been ashamed.” Actually I think the sharing of his inner self and its stark truths is his finest act of heroism.

I got to know Pat Conroy partly because he had read and admired the oral biography I did with Eugene Walter, whom he knew. After several years of a long-distance friendship conducted on the telephone, Conroy remarked one day that if I’d been recording our conversations, I’d have a book by now. It wasn’t too long after he made that remark that I began recording our conversations.

When someone once asked him why he collaborated with me on this book, Conroy replied, “My vanity got the better of my false modesty.” Although I love that response, I believe he was being—as usual—comically self-deprecating. A more serious and true answer to that question can be found I think in The Lords of Discipline, when the protagonist Will McLean reacts to the cruelties and injustices he experiences by vowing to himself: “I shall bear witness against them.” Conroy himself suffered cruelties and injustices throughout his life, from the time he was a child beaten by a violent and abusive father. The man who emerged from the crucible of chronic trauma was a warrior of words, determined to bear witness to the wrongs inflicted on the innocent and vulnerable by the corrupt and powerful. Pat Conroy never stopped being such a warrior, never ceased in his mission to bear witness against all kinds of evil, both individual and institutional. His desire to do this book with me was an extension of this mission, especially as he realized there were many aspects of his life to which he had not yet borne witness. But it was never vanity or ego that drove him to share so much about his life with his readers. Rather it was a desire to put the pain he had endured to good use, and share it with others whose own pain might be diminished as they read about his.

Then there is also this: Pat just loved to talk. He had a “compulsive need for friends and good conversation,” as he says about himself in The Water Is Wide. “I love people and collect friends like some people collect coins or exotic pipes.” A friend of his once explained that Pat conducted a major part of his social life on the telephone, and after a day of writing, when he was exhausted from his labors and in need of human contact, he would start calling friends. For many years his number-one “telephone friend” was the cartoonist Doug Marlette, whose nephew Andy reports, “They were talk-on-the-phone-every-day-for-hours best friends. I do not know what they talked about other than everything. National headlines and college basketball.” It was not long after Doug’s death in a car crash in 2007 that I met Pat and was added to his roster of “phone friends.” When I began receiving calls from him two or three times a week for an hour or two at a time, I realized that Pat Conroy lived his life through words, first in his writing and then in talking. He particularly loved conversing on the phone, I think, because it was a way of interacting entirely through words. It was another forum for telling stories, another exercise in language.

In his books the author wanted to give vent to anguish and suffering, but the man who called me on the phone wanted laughs. Laughter was a tonic he needed to share with someone, especially after a day of wrestling with his demons alone in the writing trenches. But the kind of tonic that worked for him did not come cheaply or easily. The laughter he needed had to be well earned, and it came from telling tales of the abyss—of pain, grief, sadness, despair, disappointment, failure, folly—and finding the words that made comedy instead of tragedy out of the human predicament. He referred to it as his “high gross comedy.”

As Andy Marlette observed, he loved to talk about absolutely anything, especially if a good story could be made out of it. He also loved to joke and tease, to rail playfully against fate and the gods and whoever or whatever rubbed him the wrong way. But when someone or something rubbed him the right way, he was exuberant in his delight, lavish with praise. When it came to literature, life, and human nature, he could decry the worst and celebrate the best with equal fervor.

On a fellow writer he didn’t like: “He’s one of two men who gave me the address of his tailor in London.” (That right there is one of the best put-downs I’ve ever heard, but there’s more.) “He was one of two men who wanted me to get nightshirts, and I said, ‘You mean those things you wear in Night before Christmas and All Through the House?’ He says yeah. I said, ‘I can’t imagine my bride from poor Alabama, me lumbering toward her with a lustful look in my eye, wearing a nightshirt and one of those hats.’”

On his friend Jonathan Carroll’s novel The Land of Laughs: “I started reading it, and on about the tenth page, one dog starts talking to another, and I thought, ‘Oh, fuck.’ Yet, I couldn’t wait to hear what the dog said! And I realized I was hooked. It’s a great book; I love that book.”

Although he had significant and necessary enmities—with racists, bigots, censors, and bullies—Conroy was much more lover than hater. Jonathan Carroll used to tease him for his “life-embracing quality,” his “gulp-down-the-world, glory-in-the-world-and-all-its-fruits attitude.” Doug Marlette used to joke that Pat “let everybody into the ark eventually.” Pat told me, “Doug teased me hilariously. He said, ‘You’ve wrapped yourself around all human life, embraced it all—the good, the bad, the idiots, the disgusting—and in the end of this full Conroy embrace, you let them all into the ark.” About himself Pat said: “I am a great appreciator. When I appreciate something, if it excites me, if it stimulates me, I can show that. I’ve taken great joy in the world, in a lot of what I found in it. Landscapes, geographies, cities, travel, great food, great wines, great books. I’ve loved it all.” Perhaps the best thing about conversing with him was being infected by his enthusiasms.

Participating in a co

nversation with him was like playing a sport; it was a verbal tennis game. He was nimble and agile, always able to get to the conversational ball and keep the rally going, or hit a winner. He relished the challenge of whatever came back at him from the other side of the net. Doug Marlette used to say that Pat had “the quickest response time of anyone.” Coming up with the perfect one-liner, clever rejoinder, or witty remark only after the moment had passed was never his problem. Wisecracks were his specialty, and they were always as perfectly timed as they were original.

About our project he said, “I’ll try to think deep thoughts, and I will try to be witty, literate, hilarious, and of the ages. That is what I’ll try to be.” And that is what he was, whether trying to rise to some occasion in our interviews, or just calling me “to gossip and bullshit,” as he put it.

Although I spent a very limited amount of time in person with Pat Conroy—who lived two states away—we developed a close friendship because it evolved through his favorite medium, the elixir of words. He once even told me I was better on the phone than I was in person. (He later claimed that was a joke, but I don’t believe him.)

A few of our recorded conversations took place in person, but most took place over the telephone, just as our friendship itself had developed. From March 2014 through August 2014 we spoke every day, Monday through Friday, at 9 A.M. my time, 10 A.M. Conroy’s time. These conversations lasted an hour to an hour and a half. Usually I was greeted as Madame Ice Pick, Lady Rottweiler, or Dr. Bust-My-Balls, and invited to “proceed with the evisceration, open me up and see what’s there with your probing, tooth-pulling, ball-breaking questions of the morning.” He used to complain that he had lost a best friend and gained a grand inquisitor who came with scalpel, blades, and Roto-Rooters to “excavate” his “worn-down body.” At the end of the hour, Conroy was apt to say something like, “Let me ask you this: after this depth charge into my belly, what do I do with the flood of intestines spilling over the side of my bed? What do I do with my heart in my hand, pumping its last few beats before I recede into a terrible life? My eyes are bleeding out of my head; my eyeballs are down to my belly button. What do I do about all that? Take an aspirin and go back to bed?”