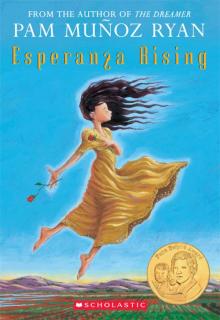

Esperanza Rising

Pam Muñoz Ryan

TO THE MEMORY OF

ESPERANZA ORTEGA MUÑOZ HERNANDEZ ELGART,

MI ABUELITA.

BASKETS OF GRAPES TO MY EDITOR,

TRACY MACK, FOR PATIENTLY WAITING

FOR FRUIT TO FALL.

ROSES TO OZELLA BELL, JESS MARQUEZ,

DON BELL, AND HOPE MUÑOZ BELL

FOR SHARING THEIR STORIES.

SMOOTH STONES AND YARN DOLLS TO

ISABEL SCHON, PH.D., LETICIA GUADARRAMA,

TERESA MLAWER, AND MACARENA SALAS

FOR THEIR EXPERTISE AND ASSISTANCE.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Aguascalientes, Mexico 1924

Las Uvas Grapes Six Years Later

Las Papayas Papayas

Los Higos Figs

Las Guayabas Guavas

Los Melones Cantaloupes

Las Cebollas Onions

Las Almendras Almonds

Las Ciruelas Plums

Las Papas Potatoes

Los Aguacates Avocados

Los Espárragos Asparagus

Los Duraznos Peaches

Las Uvas Grapes

Author’s Note

After Words

About the Author

Q&A with Pam Muñoz Ryan

Make Your Own Jamaica Flower Punch (Hibiscus Flower Punch)

Making Mama's Yarn Doll

Those Familiar Sayings

What Story Do You Have to Tell?

A Sneak Peek at Becoming Naomi Leon

Copyright

Aquel que hoy se cae, se levantará mañana.

He who falls today may rise tomorrow.

Es más rico el rico cuando empobrece que

el pobre cuando enriquece.

The rich person is richer when he

becomes poor, than the poor person

when he becomes rich.

— MEXICAN PROVERBS

“Our land is alive, Esperanza,” said Papa, taking her small hand as they walked through the gentle slopes of the vineyard. Leafy green vines draped the arbors and the grapes were ready to drop. Esperanza was six years old and loved to walk with her papa through the winding rows, gazing up at him and watching his eyes dance with love for the land.

“This whole valley breathes and lives,” he said, sweeping his arm toward the distant mountains that guarded them. “It gives us the grapes and then they welcome us.” He gently touched a wild tendril that reached into the row, as if it had been waiting to shake his hand. He picked up a handful of earth and studied it. “Did you know that when you lie down on the land, you can feel it breathe? That you can feel its heart beating?”

“Papi, I want to feel it,” she said.

“Come.” They walked to the end of the row, where the incline of the land formed a grassy swell.

Papa lay down on his stomach and looked up at her, patting the ground next to him.

Esperanza smoothed her dress and knelt down. Then, like a caterpillar, she slowly inched flat next to him, their faces looking at each other. The warm sun pressed on one of Esperanza’s cheeks and the warm earth on the other.

She giggled.

“Shhh,” he said. “You can only feel the earth’s heartbeat when you are still and quiet.”

She swallowed her laughter and after a moment said, “I can’t hear it, Papi.”

“Aguántate tantito y la fruta caerá en tu mano,” he said. “Wait a little while and the fruit will fall into your hand. You must be patient, Esperanza.”

She waited and lay silent, watching Papa’s eyes.

And then she felt it. Softly at first. A gentle thumping. Then stronger. A resounding thud, thud, thud against her body.

She could hear it, too. The beat rushing in her ears. Shoomp, shoomp, shoomp.

She stared at Papa, not wanting to say a word. Not wanting to lose the sound. Not wanting to forget the feel of the heart of the valley.

She pressed closer to the ground, until her body was breathing with the earth’s. And with Papa’s. The three hearts beating together.

She smiled at Papa, not needing to talk, her eyes saying everything.

And his smile answered hers. Telling her that he knew she had felt it.

Papa handed Esperanza the knife. The short blade was curved like a scythe, its fat wooden handle fitting snugly in her palm. This job was usually reserved for the eldest son of a wealthy rancher, but since Esperanza was an only child and Papa’s pride and glory, she was always given the honor. Last night she had watched Papa sharpen the knife back and forth across a stone, so she knew the tool was edged like a razor.

“Cuídate los dedos,” said Papa. “Watch your fingers.”

The August sun promised a dry afternoon in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Everyone who lived and worked on El Rancho de las Rosas was gathered at the edge of the field: Esperanza’s family, the house servants in their long white aprons, the vaqueros already sitting on their horses ready to ride out to the cattle, and fifty or sixty campesinos, straw hats in their hands, holding their own knives ready. They were covered top to bottom, in long-sleeved shirts, baggy pants tied at the ankles with string, and bandanas wrapped around their foreheads and necks to protect them from the sun, dust, and spiders. Esperanza, on the other hand, wore a light silk dress that stopped above her summer boots, and no hat. On top of her head a wide satin ribbon was tied in a big bow, the tails trailing in her long black hair.

The clusters were heavy on the vine and ready to deliver. Esperanza’s parents, Ramona and Sixto Ortega, stood nearby, Mama, tall and elegant, her hair in the usual braided wreath that crowned her head, and Papa, barely taller than Mama, his graying mustache twisted up at the sides. He swept his hand toward the grapevines, signaling Esperanza. When she walked toward the arbors and glanced back at her parents, they both smiled and nodded, encouraging her forward. When she reached the vines, she separated the leaves and carefully grasped a thick stem. She put the knife to it, and with a quick swipe, the heavy cluster of grapes dropped into her waiting hand. Esperanza walked back to Papa and handed him the fruit. Papa kissed it and held it up for all to see.

“¡La cosecha!” said Papa. “Harvest!”

“¡Ole! ¡Ole!” A cheer echoed around them.

The campesinos, the field-workers, spread out over the land and began the task of reaping the fields. Esperanza stood between Mama and Papa, with her arms linked to theirs, and admired the activity of the workers.

“Papi, this is my favorite time of year,” she said, watching the brightly colored shirts of the workers slowly moving among the arbors. Wagons rattled back and forth from the fields to the big barns where the grapes would be stored until they went to the winery.

“Is the reason because when the picking is done, it will be someone’s birthday and time for a big fiesta?” Papa asked.

Esperanza smiled. When the grapes delivered their harvest, she always turned another year. This year, she would be thirteen. The picking would take three weeks and then, like every other year, Mama and Papa would host a fiesta for the harvest. And for her birthday.

Marisol Rodríguez, her best friend, would come with her family to celebrate. Her father was a fruit rancher and they lived on the neighboring property. Even though their houses were acres apart, they met every Saturday beneath the holm oak on a rise between the two ranches. Her other friends, Chita and Bertina, would be at the party, too, but they lived farther away and Esperanza didn’t see them as often. Their classes at St. Francis didn’t start again until after the harvest and she couldn’t wait to see them. When they were all together, they talked about one thing: their Quinceañeras, the presentation parties they would have when they turned fifteen. They still had two more years to wait, b

ut so much to discuss — the beautiful white gowns they would wear, the big celebrations where they would be presented, and the sons of the richest families who would dance with them. After their Quinceañeras, they would be old enough to be courted, marry, and become las patronas, the heads of their households, rising to the positions of their mothers before them. Esperanza preferred to think, though, that she and her someday-husband would live with Mama and Papa forever. Because she couldn’t imagine living anywhere other than El Rancho de las Rosas. Or with any fewer servants. Or without being surrounded by the people who adored her.

It had taken every day of three weeks to put the harvest to bed and now everyone anticipated the celebration. Esperanza remembered Mama’s instructions as she gathered roses from Papa’s garden.

“Tomorrow, bouquets of roses and baskets of grapes on every table.”

Papa had promised to meet her in the garden and he never disappointed her. She bent over to pick a red bloom, fully opened, and pricked her finger on a vicious thorn. Big pearls of blood pulsed from the tip of her thumb and she automatically thought, “bad luck.” She quickly wrapped her hand in the corner of her apron and dismissed the premonition. Then she cautiously clipped the blown rose that had wounded her. Looking toward the horizon, she saw the last of the sun disappear behind the Sierra Madre. Darkness would settle quickly and a feeling of uneasiness and worry nagged at her.

Where was Papa? He had left early that morning with the vaqueros to work the cattle. And he was always home before sundown, dusty from the mesquite grasslands and stamping his feet on the patio to get rid of the crusty dirt on his boots. Sometimes he even brought beef jerky that the cattlemen had made, but Esperanza always had to find it first, searching his shirt pockets while he hugged her.

Tomorrow was her birthday and she knew that she would be serenaded at sunrise. Papa and the men who lived on the ranch would congregate below her window, their rich, sweet voices singing Las Mañanitas, the birthday song. She would run to her window and wave kisses to Papa and the others, then downstairs she would open her gifts. She knew there would be a porcelain doll from Papa. He had given her one every year since she was born. And Mama would give her something she had made: linens, camisoles or blouses embroidered with her beautiful needlework. The linens always went into the trunk at the end of her bed for algún día, for someday.

Esperanza’s thumb would not stop bleeding. She picked up the basket of roses and hurried from the garden, stopping on the patio to rinse her hand in the stone fountain. As the water soothed her, she looked through the massive wooden gates that opened onto thousands of acres of Papa’s land.

Esperanza strained her eyes to see a dust cloud that meant riders were near and that Papa was finally home. But she saw nothing. In the dusky light, she walked around the courtyard to the back of the large adobe and wood house. There she found Mama searching the horizon, too.

“Mama, my finger. An angry thorn stabbed me,” said Esperanza.

“Bad luck,” said Mama, confirming the superstition, but she half-smiled. They both knew that bad luck could mean nothing more than dropping a pan of water or breaking an egg.

Mama put her arms around Esperanza’s waist and both sets of eyes swept over the corrals, stables, and servants’ quarters that sprawled in the distance. Esperanza was almost as tall as Mama and everyone said she would someday look just like her beautiful mother. Sometimes, when Esperanza twisted her hair on top of her head and looked in the mirror, she could see that it was almost true. There was the same black hair, wavy and thick. Same dark lashes and fair, creamy skin. But it wasn’t precisely Mama’s face, because Papa’s eyes were there too, shaped like fat, brown almonds.

“He is just a little late,” said Mama. And part of Esperanza’s mind believed her. But the other part scolded him.

“Mama, the neighbors warned him just last night about bandits.”

Mama nodded and bit the corner of her lip in worry. They both knew that even though it was 1930 and the revolution in Mexico had been over for ten years, there was still resentment against the large landowners.

“Change has not come fast enough, Esperanza. The wealthy still own most of the land while some of the poor have not even a garden plot. There are cattle grazing on the big ranches yet some peasants are forced to eat cats. Papa is sympathetic and has given land to many of his workers. The people know that.”

“But Mama, do the bandits know that?”

“I hope so,” said Mama quietly. “I have already sent Alfonso and Miguel to look for him. Let’s wait inside.”

Tea was ready in Papa’s study and so was Abuelita.

“Come, mi nieta, my granddaughter,” said Abuelita, holding up yarn and crochet hooks. “I am starting a new blanket and will teach you the zigzag.”

Esperanza’s grandmother, whom everyone called Abuelita, lived with them and was a smaller, older, more wrinkled version of Mama. She looked very distinguished, wearing a respectable black dress, the same gold loops she wore in her ears every day, and her white hair pulled back into a bun at the nape of her neck. But Esperanza loved her more for her capricious ways than for her propriety. Abuelita might host a group of ladies for a formal tea in the afternoon, then after they had gone, be found wandering barefoot in the grapes, with a book in her hand, quoting poetry to the birds. Although some things were always the same with Abuelita — a lace-edged handkerchief peeking out from beneath the sleeve of her dress — others were surprising: a flower in her hair, a beautiful stone in her pocket, or a philosophical saying salted into her conversation. When Abuelita walked into a room, everyone scrambled to make her comfortable. Even Papa would give up his chair for her.

Esperanza complained, “Must we always crochet to take our minds off worry?” She sat next to her grandmother anyway, smelling her ever-present aroma of garlic, face powder, and peppermint.

“What happened to your finger?” asked Abuelita.

“A big thorn,” said Esperanza.

Abuelita nodded and said thoughtfully, “No hay rosa sin espinas. There is no rose without thorns.”

Esperanza smiled, knowing that Abuelita wasn’t talking about flowers at all but that there was no life without difficulties. She watched the silver crochet needle dance back and forth in her grandmother’s hand. When a strand of hair fell into her lap, Abuelita picked it up and held it against the yarn and stitched it into the blanket.

“Esperanza, in this way my love and good wishes will be in the blanket forever. Now watch. Ten stitches up to the top of the mountain. Add one stitch. Nine stitches down to the bottom of the valley. Skip one.”

Esperanza picked up her own crochet needle and copied Abuelita’s movements and then looked at her own crocheting. The tops of her mountains were lopsided and the bottoms of her valleys were all bunched up.

Abuelita smiled, reached over, and pulled the yarn, unraveling all of Esperanza’s rows. “Do not be afraid to start over,” she said.

Esperanza sighed and began again with ten stitches.

Softly humming, Hortensia, the housekeeper, came in with a plate of small sandwiches. She offered one to Mama.

“No, thank you,” said Mama.

Hortensia set the tray down and brought a shawl and wrapped it protectively around Mama’s shoulders. Esperanza couldn’t remember a time when Hortensia had not taken care of them. She was a Zapotec Indian from Oaxaca, with a short, solid figure and blue-black hair in a braid down her back. Esperanza watched the two women look out into the dark and couldn’t help but think that Hortensia was almost the opposite of Mama.

“Don’t worry so much,” said Hortensia. “Alfonso and Miguel will find him.”

Alfonso, Hortensia’s husband, was el jefe, the boss, of all the field-workers and Papa’s compañero, his close friend and companion. He had the same dark skin and small stature as Hortensia, and Esperanza thought his round eyes, long eyelids, and droopy mustache made him look like a forlorn puppy. He was anything but sad, though. He loved the land as Pap

a did and it had been the two of them, working side by side, who had resurrected the neglected rose garden that had been in the family for generations. Alfonso’s brother worked in the United States so Alfonso always talked about going there someday, but he stayed in Mexico because of his attachment to Papa and El Rancho de las Rosas.

Miguel was Alfonso and Hortensia’s son, and he and Esperanza had played together since they were babies. At sixteen, he was already taller than both of his parents. He had their dark skin and Alfonso’s big, sleepy eyes, and thick eyebrows that Esperanza always thought would grow into one. It was true that he knew the farthest reaches of the ranch better than anyone. Since Miguel was a young boy, Papa had taken him to parts of the property that even Esperanza and Mama had never seen.

When she was younger, Esperanza used to complain, “Why does he always get to go and not me?”

Papa would say, “Because he knows how to fix things and he is learning his job.”

Miguel would look at her and before riding off with Papa, he would give her a taunting smile. But what Papa said was true, too. Miguel had patience and quiet strength and could figure out how to fix anything: plows and tractors, especially anything with a motor.

Several years ago, when Esperanza was still a young girl, Mama and Papa had been discussing boys from “good families” whom Esperanza should meet someday. She couldn’t imagine being matched with someone she had never met. So she announced, “I am going to marry Miguel!”

Mama had laughed at her and said, “You will feel differently as you get older.”

“No, I won’t,” Esperanza had said stubbornly.

But now that she was a young woman, she understood that Miguel was the housekeeper’s son and she was the ranch owner’s daughter and between them ran a deep river. Esperanza stood on one side and Miguel stood on the other and the river could never be crossed. In a moment of self-importance, Esperanza had told all of this to Miguel. Since then, he had spoken only a few words to her. When their paths crossed, he nodded and said politely, “Mi reina, my queen,” but nothing more. There was no teasing or laughing or talking about every little thing. Esperanza pretended not to care, though she secretly wished she had never told Miguel about the river.