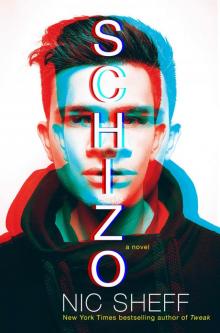

Schizo

Nic Sheff

PHILOMEL BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Nic Sheff.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sheff, Nic. Schizo / Nic Sheff. pages cm Summary: A teenager recovering from a schizophrenic breakdown is driven to the point of obsession to find his missing younger brother and becomes wrapped up in a romance that may or may not be the real thing. [1. Schizophrenia—Fiction. 2. Mental illness—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.S541155Sc 2014 [Fic]—dc23 2013038592

ISBN 978-0-698-17143-5

Crow images courtesy of iStock

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Quote from “God,” written by John Lennon, Copyright © 1980 Lenono Music. Used by permission/All rights reserved.

Quote from “Dear Yoko,” written by John Lennon, Copyright © 1980 Lenono Music. Used by permission/All rights reserved.

Version_1

to Jette . . . everything . . .

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part 2

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Part 3

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Part 4

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

I was the walrus, but now I am John.

—John Lennon

1.

IT’S STARTING AGAIN.

There’s a sound like an airplane descending loudly in my ear. I can’t quite place it. The sweat is cold down my back. I feel my heart beat faster. My hands shake.

God, I can’t take it.

I can’t.

If it happens again . . .

I hold my breath, waiting.

The sound fades in and out—high-pitched, whining.

Preston and Jackie don’t seem to notice.

They’re on his bed together, which is really just like a futon on the floor, watching this old Billy Wilder movie.

Preston’s arm is around her, and her arm is around him.

They are tangled together . . . intertwined.

Two separate people joined together into someone new and different, but still the same.

Not that I don’t like Jackie. I mean, she’s great. She’s super great. And super nice.

They both are.

That’s why they let me hang out with them.

’Cause, believe me, I bring nothing to the table.

I’m totally what you’d call a charity case.

They let me hang out and watch movies and play video games until finally Preston’ll give me a look like, Yo, me’n my girl need to have some sex right now. And so then I’ll leave.

And go home—back to my family’s little three-bedroom house on the avenues, the opposite of Preston’s palatial mansion up here near the Palace of the Legion of Honor. The house is like an old Gothic castle, paid for by the network TV show both his parents were on in the nineties. They played a couple on the show—a pair of married lawyers.

They’re retired and they spend most of their time traveling.

Leaving Preston alone with no one but Olivia, the housekeeper.

And Jackie, of course.

Sometimes I like to think that Preston and Jackie are my parents. Except that Preston is such a big pothead. He has basically his own floor in his parents’ house with a grow room set up in the closet.

I used to smoke, too, before it made me go crazy.

But that was more than two years ago.

I’m sixteen now, and it’s been over a year since my last episode.

Only there’s this shrill, piercing scream coming in and out of auditory focus.

It’s happening again.

Preston picks up his intricately blown glass bong from the carpeted floor in front of him and takes a big hit, exhaling away from me and Jackie—being polite and all.

The thick gray smoke from his lungs smells sweet and pungent, and Preston says, “Goddamn.” And then he coughs.

Jackie looks over at me and rolls her eyes, but in a sweet way.

Her eyes are this intense green color, so if I look into them when I’m talking, I get distracted and lose my train of thought. She has a long, angular nose and is tall and thin with dark black skin. She could be, like, a high-fashion model doing runway shows or whatever. She is lovely. If I weren’t crazy maybe I could have a girl like her.

But it’s not just that.

Preston is . . .

I don’t even know.

He is everything.

And he has everything.

If she’s like a high-fashion model, then he’s like some kinda rock star. He has long hair parted down the middle and a scruffy beard and square jaw. He’s tall and naturally muscular, and it’s just the way he carries himself, like he doesn’t care at all.

Really, he’s been this way ever since I can remember—calm and collected and unconcerned.

Preston and I met back when we were both ten years old going to this summer camp down in Watsonville right after his grandmother died. He used to stay up nights talking to me about her. Preston still makes, like, this big deal about it. I didn’t think I did anything that special, but I guess it meant a lot to him.

We’ve been best friends ever since—even though I didn’t start actually going to school with him until my mom got the job working in the library at Stanyan Hi

ll my seventh grade year. It’s a private school, so otherwise we’d never have been able to afford it. My mom and dad kept talking about how much better an education I’d get at Stanyan, but all I cared about was being able to hang out with Preston more.

I watch him on the bed watching the movie. His arm is around Jackie, and he’s resting his head absently on her shoulder. He’s wearing a ripped hoodie over a vintage David Bowie T-shirt, sitting cross-legged, staring at the TV with a stoned innocence—smiling.

Jackie absently strokes his hair and then kisses him on the forehead.

They are so effortless together.

And then there is that noise again—buzzing, screaming—darting in and out.

I look around.

But I am sure now that this noise is not a real noise at all. This noise is my disease—nothing but corroded synapses and misfiring chemical reactions.

Just when I’d started to think things were getting back to normal again, the medication must’ve stopped working.

The air is thick and greasy-feeling from the pot smoke and the incense and our collective breathing.

I fumble to get a cigarette out of my pack.

“Miles, you all right?” Jackie whispers—staring like she wants to see inside of me to figure out the answer to her question.

I space out into her eyes for a second.

“W- . . . what? No. I mean, yeah, I’m fine.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah,” I tell her. “Totally.”

But Preston’s room is suddenly hot and claustrophobic-feeling, and the sweat on my skin is itching fucking bad. The shades are drawn and the windows are closed, and the only light is coming from the TV. I’m sitting on the carpeted floor next to Preston’s bed, wanting to scratch my back, my arms, everywhere, but not doing it ’cause Jackie is still trying to figure out if I’m all right.

“You wanna go smoke a cigarette?” she asks me.

I pause, listening for that sound.

“Miles?”

And that’s when I see it.

Right there, on Jackie’s bare shoulder, there is this giant mosquito. I watch as it hovers and lands and then sticks her and she calls out, “Ow, fuck!”

She slaps at her shoulder, squishing the thing against her so it kind of pops, leaving behind some blackish-looking guts and whatever amount of her blood it had managed to extract before getting dead.

“What?” Preston asks her, his voice hoarse. “What is it, baby?”

She wipes the blood and bits of splattered insect away with her hand. “Aw, gross, a mosquito.”

Preston leans over to look. “In here?”

She laughs a little. “Uh, yeah . . . duh.”

She grabs some Kleenex out of a box near the bed and wipes her hand clean, throwing the wadded-up tissue in the small black plastic trash bin.

And that’s when she notices me—smiling big, rocking back and forth.

“What?” she asks, crossing her arms.

“It was a mosquito,” I tell her.

She stares blankly. “And?”

I laugh and shake my head.

She keeps on staring at me.

"Are you sure you're all right?"

I go on and laugh some more.

Because, I mean, that’s the fucking question, isn’t it?

2.

DR. FRANKEL IS SHORT, practically a midget.

When he sits in his plush leather office chair, his legs dangle two or three inches off the ground. The ground, in this case, being some kind of Persian tapestry rug over a hardwood floor—a rug covered in patterns like abstract palm trees—a rug I've stared at and tried to decipher at least five thousand times in the last two years.

I’m not sure how my parents found this guy. Or how they’re paying for him.

What I do know is that my visits have finally been cut down to twice a month—so I guess I’ll be staring at that goddamn pattern a little less now, won’t I?

Dr. Frankel coughs.

Besides being incredibly short, he is also incredibly fat. He has these giant bushy eyebrows and a huge nose and a gullet neck and he wears shiny tracksuits like a mobster. Really, I think the reason I stare at the carpet so much is that he’s actually kind of hard to look at.

But, I mean, I guess he’s a pretty good doctor. The meds I’m on right now seem to be working—and that is the point.

“Miles, my boy.”

That’s what he always calls me.

I’m not sure how I feel about that.

“Miles, my boy, how have things been? Better?”

He’s eating baby carrots out of a bag, so I keep my eyes focused on that strangely patterned rug of his.

“Uh, I don’t know.”

I cross and uncross my legs.

He crunches noisily.

“The Zyprexa seems to be a winner, no?”

My eyes drift over to the built-in shelves with the rows and rows of different self-help books and things. A bunch of them he actually wrote himself—including the newest one: Schizophrenia in the Adolescent Male: Signs, Symptoms, and Treatments.

That’s the one he wrote about me.

Well, me and these two other kids I see, separately, in the waiting room from time to time. Not that I’ve ever spoken to them. I’ve never talked to anyone else with this disease.

And, of course, I haven’t read his book, either.

If I want to see other schizophrenics, I don’t really have to look too far. This is San Francisco. I see ’em standing on every street corner downtown—yelling at cars and talking to shit that isn’t there.

Those are my peers: the people who construct helmets out of plastic coolers and cardboard boxes, trying to keep the voices out. The people whose clothes are so black with dirt and oil, it looks like they’re wearing sealskin. The people whose hair is tangled together into a nest of fleas and lice and whatever else. The people who have no homes or families or friends. The people walking down the street with their pants around their ankles, shitting as they go.

I’ve seen it, man. This city’s full of them. My dad wrote this big article about it for the Chronicle a few years ago, claiming it goes back to the eighties, when Reagan cut funding for mental health programs. They were all thrown out into the street, and there they’ve fucking stayed.

But now, from what Dr. Frankel says, it’s getting seriously more common, like, all the time. There was even another schizo kid at my school who had to go off to some institution at the beginning of last year. I never met him or anything, but, of course, everyone heard the story. Dan Compton, his name was. And I think half the kids in school probably expect me to go the same way.

I don’t blame them. Some days, I expect the same thing. It scares the shit out of me even though, as Dr. Frankel keeps telling me, I’m the lucky one—the one the medication’s been working for.

And, yeah, to answer the good doctor’s question, Zyprexa seems all right.

I tell him that.

He chuckles.

“Good, Miles, good. Carrot?”

I glance up and look at the carrot he’s holding out to me. The color is, like, bright, toxic orange. Really, it’s the most vividly fucking orange carrot I’ve ever seen.

“Uh, no. I’m okay . . . thanks.”

My eyes go back to the rug and then the bookshelf and then the rug again.

“How about the other medications? Are the side effects any more tolerable?”

I swivel around in my chair. “I don’t know.”

He crunches loudly, smacking his lips together. “You don’t know?”

“Well,” I say, “I still get hella nauseous when I take ’em all at once.”

“So, maybe don’t take them all at once.”

I laugh. “Yeah, I know. But it’s hard to remember otherwise.”<

br />

He suggests I make myself a schedule, and I think that’s pretty fucking obvious. I do some more swiveling while he does some more crunching.

“Plus, didn’t I tell you?” I add. “My mom says her insurance won’t cover ’em anymore ’cause the school, like, cut her hours or something.”

His mouth turns down at the corners. “But aren’t you working at that grocery store on the weekends?”

I laugh again. “Yeah, but that’s, like, minimum wage. I mean, it’s nothing.”

He shakes his head. “Hmmm. Well, let me see what I can do, okay, Miles? You really shouldn’t be worrying about these things. Your job is to get well. Let your parents be your parents. And let yourself be a kid—at least for a little while longer.”

I pause for a second, cracking the knuckles on my left hand.

“I don’t know,” I say. “I mean, sometimes I don’t even see the point of all this. It’s like, what kind of life can I possibly expect to have? You think I’m gonna hold a job, get married, have a family?”

Dr. Frankel stops crunching, and I can hear the chair creak as he leans forward.

“You can do anything you want.”

“Yeah, right.”

“I’m serious, Miles. Your life is just beginning.”

Yeah. Just beginning, I think. But it’s already over.

My face contorts, and I wonder if maybe I shouldn’t say what I’m about to say, but I go ahead and say it anyway.

“I appreciate you trying to give me hope and all. But I know what my chances are. It seems like I’d be doing everyone a favor if I could just end it, you know?”

He shakes his head again, and his gullet goes along for the ride, flapping back and forth. I can smell something stale and sour suddenly, like maybe he forgot to put on deodorant this morning.

“Miles, are you listening to yourself? You don’t think your parents would be absolutely, cataclysmically devastated to lose you?”

“Yeah, sure, of course,” I tell him, averting my eyes again. “But, at least, then it would be over, all at once. The way it is now, I’m just gonna drag this fucking thing out so they can’t ever move past it. You see what I’m saying?”

Dr. Frankel speaks gently. “Miles, come on, look at me.”

I don’t want to do it, but I’m too goddamn polite not to. I raise my head up as he leans in even closer.