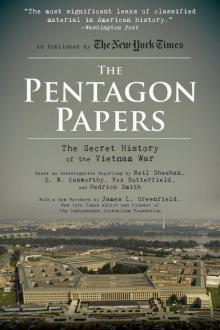

Pentagon Papers

Neil Sheehan

Copyright © by The New York Times Company

First published in 1971 by Quadrangle Books, Inc.

First Racehorse Publishing Edition 2017

No copyright is claimed in official government documents contained in this volume.

All rights to any and all materials in copyright owned by the publisher are strictly reserved by the publisher.

Foreword © 2017 James L. Greenfield

Racehorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Racehorse Publishing™ is a pending trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Michael Short

Cover photograph: Pixabay

Print ISBN: 978-1-63158-292-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63158-293-6

Printed in the United States of America

NEW YORK TIMES STAFF FOR THE PENTAGON PAPERS

Managing Editor: A. M. Rosenthal

Project Editor: James L. Greenfield

Editors: Gerald Gold, Allan M. Siegal, Samuel Abt

Assisting Editors: Max Lowenthal, Richard McSorley, Betsy Wade, Werner Wiskari

Research: Linda Amster

Photo Research: Phyllis Collazo

Biographies and Highlights: Linda Charlton

Editorial Assistants: Eileen Butler, Vincent Caltagirone, Marie Courtney, Gail Fresco, Catherine Patitucci, Robert J. Rosenthal, Catherine L. Shea, Muriel Stokes, Leslie A. Tonner

Contents

Foreword by James L. Greenfield

Introduction by Neil Sheehan

Chapter 1 The Truman and Eisenhower Years: 1945-1960 by Fox Butterfield

Chapter 2 Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam by Fox Butterfield

Chapter 3 The Kennedy Years: 1961-1963 by Hedrick Smith

Chapter 4 The Overthrow of Ngo Dinh Diem: May-November, 1963 by Hedrick Smith

Chapter 5 The Covert War and Tonkin Gulf: February-August, 1964 by Neil Sheehan

Chapter 6 The Consensus to Bomb North Vietnam: August, 1964-February, 1965 by Neil Sheehan

Chapter 7 The Launching of the Ground War: March-July, 1965 by Neil Sheehan

Chapter 8 The Buildup: July, 1965-September, 1966 by Fox Butterfield

Chapter 9 Secretary McNamara’s Disenchantment: October, 1966-May, 1967 by Hedrick Smith

Chapter 10 The Tet Offensive and the Turnaround by E. W. Kenworthy

Appendix 1 Analysis and Comment

The Lessons of Vietnam by Max Frankel

Editorials from The New York Times

Appendix 2 Court Records

Summary of Court Proceedings

U.S. v. New York Times Company, et al

Decision of U.S. District Court

Decision of U.S. Court of Appeals

U.S. v. The Washington Post Company, et al

Decision of U.S. District Court

Decision of U.S. Court of Appeals

Decision of U.S. District Court

Decision of U.S. Court of Appeals

Oral Argument Before the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States, Decision and Opinions

Appendix 3 Biographies of Key Figures

Index of Key Documents

Glossary

Foreword

In 1967, Robert McNamara, then President Lyndon Johnson’s secretary of defense, created a secret unit in the Pentagon to collect as many internal government documents as possible relating to the Vietnam War. McNamara hoped that the collection would give officials a clearer view of the decisions that put the United States on an increasingly crisis-ridden path. It is not clear what, if anything, McNamara learned from the project. But it is clear that he could not, and did not, anticipate the journalistic bombshell he ultimately got.

In 1971, by which time President Richard Nixon had managed to involve the United States even more deeply in the war, The New York Times published a blockbuster series of articles based on McNamara’s study. They came to be known as the Pentagon Papers, and now hold an essential place in the legacy of twentieth-century American journalism. The articles revealed, in detail and in the government’s own words, how officials had stumbled, often haphazardly, into a disastrous war that had already taken thousands of American lives.

The documents included every cable, bureaucratic memo, and note of conversation from within the government that mentioned Vietnam. They were culled not only from the White House, Pentagon, and State Department, but also from such peripheral bureaucracies as the Agriculture Department. In all, they totaled more than seven thousand documents. Their classification ranged from top secret to just plain secret.

Somewhat overwhelmed by the sheer number of classified documents, Arthur (Punch) Sulzberger, the Times publisher, asked A.M. Rosenthal, the paper’s executive editor, and me, as the appointed project editor, to brief the Times’ outside law firm, Lord Day & Lord.

“How many of the documents were classified,” the attorneys asked.

“All seven thousand,” we responded.

Shocked, the firm counseled against publishing them. When that recommendation was brushed off, Lord Day declined to represent the paper in the matter—after reportedly debating but rejecting a proposal within the firm to report the project to the Justice Department. (Years later, when asked his reaction to first hearing about the papers, Punch Sulzberger replied wryly, “Ten years to life.”)

The documents did not, as some later claimed, simply fall into the hands of The New York Times. Neil Sheehan, a Washington-based correspondent and celebrated Vietnam reporter, got a whiff of their existence, and then pursued a set of them from a senior member of the government-funded Rand Corporation, Daniel Ellsberg.

In multiple meetings between the two, Sheehan argued that Americans had a right to know how the government, especially the president, had made crucial decisions involving the war. Persuaded, Ellsberg began passing copies of the papers to Sheehan.

The copies arrived in New York in several mailbags and were eventually stashed in my Manhattan apartment, under the bed, for safe-keeping. They were then moved, suitcase by suitcase, to a makeshift editorial office set up in a suite in the Hilton Hotel. This was an essential first step. A crowded newsroom was no place for thousands of secret documents, and a leak was inevitable. Besides, our hotel hideaway allowed the editing staff to work all day and sleep in adjoining rooms at night.

From the start, our team agreed it was up to us to prove the papers’ legitimacy beyond doubt. It took weeks to spot-check hundreds of the documents against hundreds of stories already published. More than twenty books written by former government officials and laden with Vietnam references were checked against the documents to see if they matched. In every case they did.

It quickly became apparent that no one writer—even one as skilled as Neil Sheehan—could write the series alone. So Hedrick Smith, E. W. (Ned) Kenworthy, and Fox Butterfield—all veteran Vietnam reporters—were brought in. Two of the paper’s best editors—Gerald Gold and Allan Siegel, plus the Times chief librarian, Linda Amster, were recruited. Together they made sure that every sentence written corresponded to a reference in one of the documents. Adding one’s own reporting was unacceptable.

The first installment of the Pentagon Papers was published in the Times on June 13, 1971, a Sunday. The article was displayed in

the center of the front page. Inside were several pages of the actual documents reproduced verbatim.

The next day, after the second installment was published, an angry Attorney General John Mitchell sent a telegram to the paper, demanding that publication be stopped. It was, Mitchell contended, a threat to national security. The next day the Times ran an article under the headline: “Mitchell Seeks to Halt Series on Vietnam But Times Refuses.” On Tuesday, after the paper had published three articles, Federal Judge Murray Gurfein slapped a restraining order on further publication.

It was immediately clear that this issue would end up in the country’s highest court. And so it did, swiftly. Left without an outside law firm, James Goodale, the head of the Times legal department, recruited Alexander Bickel, a Yale professor and one of the country’s top constitutional experts, to represent the paper. Floyd Abrams, an up-and-coming First Amendment lawyer, was added to the team.

On June 25 and 26, 1971, the Supreme Court heard the government’s argument that further publication of the papers “would cause an irreparable harm to United States national interests.”

On June 30, by a vote of six to three, the Court disagreed and upheld the Times’s right to publish. And so the paper did, until the final installment on July 5, 1971.

The articles revealed a mounting list of problems that the government faced—and often fumbled—as the Vietnam War nearly careened out of control. Decisions were clouded by Washington politics, President Johnson’s own confused strategy, mixed signals from the battlefield, bad advice, and overconfidence, especially in evaluating an enemy’s ability to absorb punishment and continue to fight with great ferocity.

The war in Vietnam continued until April 30, 1975. By then, fifty-eight thousand Americans had been killed, more than 60 percent of them under the age of twenty-one, and three hundred thousand wounded, fighting in the jungles and hamlets and paddy fields of that Southeast Asian country.

JAMES L. GREENFIELD

September 20, 2017

Introduction

For most of the past 20 years, directly or by proxy, the United States has been waging war in Indochina. Forty-five thousand Americans have died in the fighting, 95,000 men of various nationalities in the former French colonial army, and no one knows how many Indochinese—the guesses run from one to two million. Only a very small number of men have known the inner story of how and why four succeeding Administrations, those of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson, helped to maintain this semipermanent war in Indochina—a conflict that the Administration of President Nixon has continued.

On June 17, 1967, at a time of great personal disenchantment with the war, Robert S. McNamara, who was then Secretary of Defense, made what may turn out to be one of the most important decisions in his seven years at the Pentagon. He commissioned what has since become known as the Pentagon papers—a massive top-secret history of the United States role in Indochina. The work took a year and a half. The result was approximately 3,000 pages of narrative history and more than 4,000 pages of appended documents—an estimated total of 2.5 million words. The 47 volumes cover American involvement in Indochina from World War II to May, 1968, the month the peace talks began in Paris after President Johnson had set a limit on further military commitments and revealed his intention to retire.

The New York Times obtained most of the narrative history and documents and began publishing a series of articles based on them on Sunday, June 13, 1971. After the first three daily installments appeared, the Justice Department obtained a temporary restraining order against further publication from the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York. The Government contended that if public dissemination of the history continued, “the national defense interests of the United States and the nation’s security will suffer immediate and irreparable harm,” and sought a permanent injunction. The issue was fought through the courts for 15 days, as The Times and The Washington Post, which had subsequently begun publishing articles on the history, along with other newspapers, argued that the Pentagon papers belonged in the public domain and that no danger to the nation’s security was involved.

On June 30, 1971, the Supreme Court of the United States freed the newspapers to continue publication of their articles. By a vote of 6 to 3, the justices held that the right to a free press under the First Amendment to the Constitution overrode any subsidiary legal considerations that would block publication by the news media.

The Pentagon papers, despite shortcomings and gaps, form a great archive of government decision-making on Indochina over three decades. The papers tell what decisions were made, how and why they were made and who made them. The story is told in the written words of the principal actors themselves—in their memorandums, their cablegrams and their orders—and in narrative-analyses of these documents written by the 36 authors of the history.

The authors, who functioned as anonymous government historians, aimed at the broadest possible interpretation of events. They examined not only the policies and motives of the successive Administrations concerned, but also the effect or lack of effect of intelligence analyses on policy; the mechanics and consequences of bureaucratic compromises; the dilemmas of seeking to impose American concepts on the Vietnamese; the techniques of the Executive Branch of government in influencing Congress, the news media and domestic and international opinion in general, and many other tributaries of the main historical narrative.

The narrative-analyses bear the character of a middle-echelon and institutional view of the war, for the majority of the authors were careerists, experienced State and Defense Department civilian officials and military officers, as well as defense-oriented intellectuals from government-financed research institutes. The director of the project for Mr. McNamara was Leslie H. Gelb, 30 years old at the time the history was commissioned, a Harvard Ph.D. in political science and a former head of policy planning in the Pentagon’s office of politico-military operations—International Security Affairs. The authors were promised anonymity when they were recruited for the project so that they would be free to make judgments in the course of their writing. The anonymity was designed to protect their careers if the judgments later displeased higher authority.

The anonymous character of the study, officially entitled “History of U. S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy,” was also preserved by having several authors collaborate on each of the various chronological and thematic sections. The process gave the history a fragmented character and it does not reflect consistent themes throughout, as would a history written by one author or a group of authors who shared a similar overview of events. For example, the history lacks a single, all-embracing summary and it displays a number of other inconsistencies.

The result was an extended internal critique of the appended documentary record—what Mr. Gelb, in a letter on Jan. 15, 1969, to Mr. McNamara’s successor, Clark M. Clifford, called “not so much a documentary history as a history based solely on documents—checked and rechecked with ant-like diligence.”

To preserve the secrecy of the project, the historians were forbidden to supplement the documentary record by interviewing the decision-makers themselves. And even where the documentary record was concerned, the authors could not bridge important gaps. They did not have access to the White House archives of President Johnson and to those of past Presidents, nor to the full files of the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency, although the authors did have many documents from all of these sources.

The historians relied for the documentary record on files of Mr. McNamara and Mr. Clifford, the official archives of past Defense Secretaries and those of other senior officials in the Pentagon. Into these Pentagon files had in turn flowed papers from the White House, the State Department, the C.I.A. and the office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. William Bundy, the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs in the Johnson Administration, also made available documents from his official files.

The copy of

the Pentagon papers obtained by The New York Times lacks, however, the four volumes the historians wrote on the secret diplomatic negotiations of the Johnson period. What discussion of Vietnam diplomacy since 1963 is contained in the relevant chapters of this book, therefore, has been based on the sporadic, but significant insights the other volumes of the Pentagon papers provide.

The historians themselves also found no conclusive answers to some of the most widely asked questions about the war, including these:

• Precisely how was Ngo Dinh Diem returned to South Vietnam in 1954 from exile and helped to power?

• Who took the lead in preventing the 1956 Vietnam-wide elections provided for in the Geneva accords of 1954—Mr. Diem or the Americans?

• If President Kennedy had lived, would he have led the United States into a full-scale ground war in South Vietnam and an air war against North Vietnam as President Johnson did?

• Was Secretary of Defense McNamara dismissed for opposing the Johnson strategy in mid-1967 or did he ask to be relieved because of disenchantment with Administration policy?

• Did President Johnson’s cutback of the bombing to the 20th Parallel on March 31, 1968, signal a lowering of United States objectives for the war or was it merely an effort to buy more time and patience from a war-weary American public?

But whatever their drawbacks, the Pentagon papers are the most complete secret archive of government decision-making on Indochina that has yet become available. Taken as a whole, the papers demonstrate that the four Administrations of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson progressively developed a sense of commitment to a non-Communist Vietnam, a readiness to fight the North to protect the South, and an ultimate frustration with this effort—to a much greater extent than their public statements acknowledged at the time. The historians were led to many broad conclusions and specific findings, including the following:

• That the Truman Administration’s decision to give military aid to France in her colonial war against the Communist-led Vietminh “directly involved” the United States in Vietnam and “set” the course of American policy.