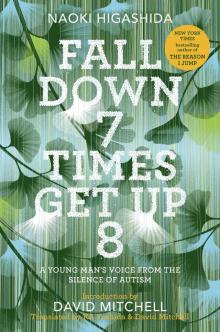

Fall Down 7 Times Get Up 8: A Young Man's Voice From the Silence of Autism

Naoki Higashida

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright © 2017 by Naoki Higashida and David Mitchell Text

Translation copyright © 2017 by KA Yoshida and David Mitchell Text

Introduction copyright © 2017 by David Mitchell Text

Illustrations copyright © 2017 by Yoco Nagamiya

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Higashida, Naoki, author.

Title: Fall down 7 times get up 8 : a young man’s voice from the silence of autism / Naoki Higashida ; translated by KA Yoshida and David Mitchell.

Other titles: Fall down seven times get up eight

Description: First edition. | New York : Random House, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004105 | ISBN 9780812997392 (hardback) | ISBN 9780812997408 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Higashida, Naoki, 1992– —Health. | Autistic people—Japan—Biography. | Autistic people—Psychology. | Autism. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Medical. | PSYCHOLOGY / Psychopathology / Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Classification: LCC RC553.A88 H52 2017 | DDC 616.85/8820092 [B]—dc23 LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2017004105

Ebook ISBN 9780812997408

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design and illustration: © Kai and Sunny

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

A Note on the English Edition

Part 1: The View from Here

Chapter 1: Mother’s Day 2011

Chapter 2: “It’s Raining!”

Chapter 3: Impossible Things

Chapter 4: Cold Baths

Chapter 5: Wrinkles

Chapter 6: Cool Clothes

Chapter 7: Band-Aids

Chapter 8: Jigsaws

Chapter 9: “Lickety-Lick”

Chapter 10: Portions

Chapter 11: Trampolines and Shuttlecocks

Chapter 12: The Bottom-Biting Bug: O-Shiri-Kajiri Mushi

Part 2: Time and Life

Chapter 13: “Hang on a Moment!”

Chapter 14: Adjustments

Chapter 15: The Day Ahead

Chapter 16: Time Management

Chapter 17: Seasons

Chapter 18: Memory Signposts

Righteousness

Chapter 19: Life, the Teacher

Chapter 20: How You Strive

Chapter 21: Success

An Alphabet Interview

Part 3: Speech Bubbles

Chapter 22: “I’m Home!” and “Welcome Back!”

Chapter 23: Words I Want to Say

Chapter 24: We’re Listening

Chapter 25: Wordlessness

Chapter 26: Not Everyone Will Understand

Rumors

Chapter 27: Questions and Answers, Answers and Questions

Chapter 28: Thoughts on Words

Words

Chapter 29: Trouble with Talking

Chapter 30: Words of Gratitude

Part 4: School Years

Chapter 31: Scissors and Glue

Chapter 32: Have Yourself a “Well Done!” Sticker

Chapter 33: My Freedom

Chapter 34: Friendlessness

Chapter 35: School

Chapter 36: Back to School

Chapter 37: New Term Shyness

Chapter 38: Lessons in Hindsight

Process

Chapter 39: Words of Praise

Chapter 40: The Way You Are

Chapter 41: Advice to My Younger Self

A Journey

Part 5: Inner Weather

Chapter 42: One Army Fighting Hard

Chapter 43: Empathy and Endurance

Chapter 44: Loneliness and Autism

“It Can’t Be Helped”

Chapter 45: Anger

Chapter 46: Laughing

Chapter 47: Thorns in the Heart

Chapter 48: Grace

Chapter 49: “The Only Flower in the World”

Chapter 50: My Dream Me

Gratitude

Part 6: Handle with Care

Chapter 51: Hitting My Head and Biting My Clothes

Chapter 52: Help

Chapter 53: Reprimands

Chapter 54: Comfort Zones

Chapter 55: Three Thoughts on Special Needs

Chapter 56: “Grooved-in” Failure

Chapter 57: “Everybody’s Doing Their Best!”

Chapter 58: Plodding Along, Tortoise-Like

Curiosity

Chapter 59: Ingrained Fixations

Chapter 60: The Gift of Choice

Chapter 61: What Would You Like to Be?

An Alphabet Interview

Part 7: Away

Chapter 62: The Gate

Chapter 63: Entry Prohibited

Chapter 64: Paying

Chapter 65: Eating Out

Chapter 66: Wanting to Vanish

Chapter 67: Chaos in the Brain

Chapter 68: Misunderstandings

Chapter 69: Say “Cheese!”

Chapter 70: Traveling

Flying

Chapter 71: New York

Part 8: Home

Chapter 72: Home

Chapter 73: Picture Books

Chapter 74: Respect

Chapter 75: Mom

Chapter 76: My Sister and I

Chapter 77: Dad

One Brilliant Dad

Chapter 78: Obstacles, Goals, Blessings and Hopes

Chapter 79: Dear Parents

Chapter 80: Mother’s Day 2013

Afterword

By Naoki Higashida

About the Author

About the Translators

Naoki Higashida is an amiable and thoughtful young man now in his early twenties who lives with his family in Chiba, a prefecture adjacent to Tokyo. Naoki has autism of a type labeled severe and nonverbal, so a free-flowing conversation of the kind that facilitates the lives of most of us is impossible for him. By dint of training, stamina and patience, however, he has learned to communicate by “typing out” sentences on an alphabet grid—a QWERTY keyboard layout drawn on a sheet of card with an added “YES,” “NO” and “FINISHED.” Naoki voices the phonetic characters of the Japanese hiragana alphabet as he touches the corresponding Roman letters and builds up sentences, which a transcriber takes down. (Nobody else’s hand is near Naoki’s during this process, a point that alphabet-grid communicators in a skeptical world need to restate ad infinitum.) If this sounds like an arduous way to get your meaning across, you’re right, it is; in addition, Naoki’s autism bombards him with distractions and prompts him to get up mid-sentence, pace the room and gaze out of the window. He is easily ejected from his train of thought and forced to begin the sentence again. I’ve watched Naoki produce a complex sentence within sixty seconds, but I’ve also seen him take twenty minutes to complete a line of just a few words. By writing on a laptop Naoki can dispense with the human transcriber, but the screen and the text-converter (the drop-down menus required for writing Japanese) add a new layer of distraction. It was via his alphabet grid or his computer keyboard that Naoki wrote every

sentence in this book.

I met Naoki’s writing before I met Naoki. My son has autism and my wife is from Japan, so when our boy was very young and his autism at its most grimly challenging, my wife searched online for books in her native language that might offer practical insight into what we were trying (and often failing) to deal with. Internet trails led to The Reason I Jump, written when its author was only thirteen, and produced by a small specialist publisher. Our bookshelves were bending under weighty tomes by autism specialists and autism memoirs, and while many of these were worthy, few were of much “hands-on” help with our nonverbal, regularly distressed five-year-old. My wife took a punt on Naoki’s book because the author was relatively close in age to our son as well as being nonverbal. When the book arrived she began translating chunks of it out loud at our kitchen table, and many of its very short chapters shed immediate light on our son’s issues: why he banged his head on the floor; why there were phases when his clothes seemed unendurably uncomfortable; why he would be seized by fits of laughter or fury or tears even when nothing obvious had happened to provoke these reactions. Theories I’d read previously by neurotypical authors were speculations that sometimes made sense but sometimes didn’t; The Reason I Jump offered plausible explanations directly from the alphabet grid of an insider.

Illumination can mortify—I realized how poorly I’d understood my son’s autism—but a little mortification never hurt anyone. On YouTube I found a few clips of Naoki and was taken aback at how visibly manifest his autism was—more so than my own son’s. This gap between Naoki’s appearance and his textual expressiveness made a deep impression. Clearly, he struggled with meltdowns, fixations, physical and verbal tics that not so long ago would have ensured a short bleak life of incarceration. Yet in The Reason I Jump the same boy was exhibiting intelligence, creativity, analysis, empathy and an emotional range as wide as my own. What intrigued me as much as anything was that these last two attributes—empathy and emotional range—are precisely what people with autism are famous for lacking. What was going on? The severity of Naoki’s autism was documented both in the YouTube clips and in Gerardine Wurzburg’s 2010 autism documentary Wretches and Jabberers. This left me with two possibilities: either Naoki Higashida is a one-in-a-million person, who has severe nonverbal autism yet is also intellectually and emotionally intact; or society at large, and many specialists, are partly or wholly wrong about autism.

Evidence against the “uniqueness possibility” came in the form of other nonverbal writers and bloggers with severe autism such as Carly Fleischmann and (more recently) Ido Kedar and Tito Mukhopadhyay. Naoki’s ability to communicate might be rare but it’s not one in a million. The “wrong about autism” theory is bolstered by the regrettable errors that could serve as chapter headings in the history of autism. Leo Kanner, the pioneering child psychiatrist who first used the word “autism” in the 1940s in a context distinct from schizophrenia, blamed the condition in part on “refrigerator mothers”—a notion whose public credibility now is on a par with demonic possession, but which maintains some currency in France, South Korea and among an older generation of tenured experts. The 1960s and ’70s saw eminent psychiatrists advocating autism “cures” based on electrotherapy, LSD and behavioral change techniques that utilized pain and punishment. I understand that science progresses over the bodies of debunked theories, and I know that judging well-intentioned psychiatrists from the higher ground of hindsight isn’t particularly fair, but when I consider the damage they surely inflicted on children like my son, as well as on parents like me and my wife, I don’t feel like being particularly fair. The crux of the matter: what if the current mainstream assumption that people with severe autism have matching severe intellectual disabilities is our own decade’s big bad wrongness about autism? What if Naoki’s conviction—expressed in this present book—that we are mistaking communicative nonfunctionality for cognitive nonfunctionality is on the money?

My wife and I saw no harm in “assuming the best” and acting as if, inside the chaotic swirl of our son’s autisms and behaviors, there was a bright and perceptive—if grievously isolated—five-year-old. We stopped assuming that because he’d never uttered a word in his life, he couldn’t understand us. We put morsels of food he didn’t eat on the edge of his plate of pasta, like Naoki suggests, in case he was feeling experimental that day. Often he wasn’t, but sometimes he was, and his food repertoire grew. We started asking our son to pick things up that he’d dropped by taking his hand to the dropped object, instead of thinking oh, why bother? and doing it for him. Where possible we gave him choices instead of deciding things for him. We got craftier at discerning his unexpressed wishes rather than assuming his wishes were nonexistent. We began speaking to him normally, rather than sticking to one-word sentences. I didn’t know what percentage of these longer, more natural sentences our son understood—I still don’t—but I do know that our daily lives got better. I know that day by day and week by week he was more “present” and interactive. His eye contact improved, he engaged with us more, and with help from an inspired and inspiring tutor our son came into the kitchen one day and almost made me fall off my chair by asking, “Can I have orange juice please?” His vocabulary snowballed and episodes of self-harm dwindled away to near zero.

Lacking access to a parallel universe in which I’ve never heard of Naoki Higashida, I can’t know whether these steps and improvements would have come about anyway. We still had, and still have, plenty of less-than-great days. Autism is not a disease, so there are no “cures”—and never give your credit card details to anyone who tells you otherwise. To labor the point: The Reason I Jump is not a magic wand. But the book did help us understand both our son’s challenges and the world from his point of view more than any other source, and this knowledge helped us help him. Some attitudes and habits inhibit development, while other attitudes and strategies stimulate it, and Naoki’s book enabled us to identify the latter and shift a kind of pointer in our lives together from “Negative” to “Positive.”

Initially, my wife and I translated The Reason I Jump into English for our son’s special needs assistants because we thought they would also find its insights helpful. I mentioned the book to my agent and my UK editor, who asked to see our samizdat manuscript. They saw its potential interest to a public growing more tolerant of and curious about neurodiversity. My agent contacted the book’s publisher in Japan, and soon my UK, US and Canadian publishers made offers for the English translation rights. Naoki and his family accepted. Helped by a superb BBC Radio 4 serialization and an endorsement in the United States by The Daily Show’s Jon Stewart—a champion of autism awareness—The Reason I Jump entered the bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic. A documentary about Naoki and his book’s impact—What You Taught Me About My Son—was made by the Japanese state broadcaster NHK. It was during the making of this film that I first met Naoki in Tokyo, and saw for myself both the challenges he faces when he communicates and his tenacity in overcoming these challenges. After its first airing, NHK received many hundreds of phone calls and emails from viewers requesting a repeat. After its second airing, more viewers called in for a third, then a fourth, then a fifth time. To date, The Reason I Jump has been translated into more than thirty languages. To the best of my knowledge, this makes Naoki Higashida the most widely translated living Japanese author after Haruki Murakami.

I was surprised and pleased by the critical and commercial success of Naoki’s book, which matters a whole lot more to the big scheme of things than my own fiction. My involvement in the promotion of The Reason I Jump, however, gave me a crash course in the politics of special needs. It is not for the fainthearted. Entrenched opinion is well armed, and its default reaction to new ideas is often hostile. While The Reason I Jump enjoyed a positive reception, an accusation was leveled that nobody with “genuine” severe autism could possibly have authored such articulate prose: never mind the YouTube clips showing Naoki authoring this same articulate

prose. Therefore, Naoki must have been misdiagnosed and doesn’t have autism at all; or he’s an impostor at the Asperger’s Syndrome end of the spectrum, akin to the character Sheldon Cooper in The Big Bang Theory; or his books are written by someone else, possibly his mother. Or me. The New York Times reviewer cautioned the translators against “turning what we find into what we want.” (The subtext I can’t help but see here is, “These desperate parents won’t face the fact their son is a vegetable so their objectivity is compromised.”) Elsewhere, Naoki has been accused of seeking entry into the guru business. You really cannot win. Of course, Naoki hopes that his writing contributes to a better public understanding of autism, but he is all too aware of the limits imposed by autism upon his knowledge of the neurotypical world. Reading newspapers isn’t easy for him and politics can seem baffling. As an ex-pupil of a special needs school he knows that autism comes in many shapes and sizes, so his observations on autism won’t be, and can’t be, universally applicable. Naoki is nobody’s guru: he’ll answer questions as best he can, but you take what you need and leave the rest.