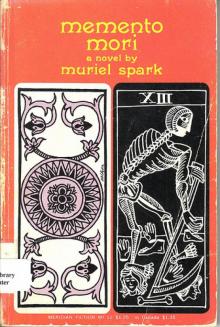

Memento Mori

Muriel Spark

Memento Mori

by MURIEL SPARK

available from New Directions:

THE ABBESS OF CREWE

ALL THE POEMS OF MURIEL SPARK

ALL THE STORIES OF MURIEL SPARK

THE BACHELORS

THE BALLAD OF PECKHAM RYE

THE COMFORTERS

THE DRIVER’S SEAT

A FAR CRY FROM KENSINGTON

THE GHOST STORIES

THE GIRLS OF SLENDER MEANS

LOITERING WITH INTENT

MEMENTO MORI

OPEN TO THE PUBLIC

THE PUBLIC IMAGE

ROBINSON

SYMPOSIUM

Muriel Spark

MEMENTO MORI

A NEW DIRECTIONS CLASSIC

Copyright © 1959 by Muriel Spark

All right reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published as a New Directions Classic in 2000

Published by arrangement with Dame Muriel Spark, and her agent Georges Borchardt, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Spark, Muriel.

Memento Mori / Muriel Spark.

p. cm.—(New Directions classics)

ISBN: 978-0-8112-1438-4

1. Aged—England—London—Fiction. 2. Aged—Psychology—Fiction. 3. Practical jokes—Fiction. 4. London (England)—Fiction. I. Title. II. Series.

PR6037.P29 M4 2000

823’.914—dc21

99-058767

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation,

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

Memento Mori

What shall I do with this absurdity—

O heart, O troubled heart—this caricature,

Decrepit age that has been tied to me

As to a dog’s tail?

—W. B. YEATS, The Tower

O what venerable and reverent creatures did the aged seem! Immortal Cherubims!

—THOMAS TRAHERNE,

Centuries of Meditation

Q. What are the four last things to be ever remembered?

A. The four last things to be ever remembered are Death, Judgment, Hell, and Heaven.

—The Penny Catechism

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter One

Dame Lettie Colston refilled her fountain pen and continued her letter:

One of these days I hope you will write as brilliantly on a happier theme. In these days of cold war I do feel we should soar above the murk & smog & get into the clear crystal.

The telephone rang. She lifted the receiver. As she had feared the man spoke before she could say a word. When he had spoken the familiar sentence she said, “Who is that speaking, who is it?”

But the voice, as on eight previous occasions, had rung off.

Dame Lettie telephoned to the Assistant Inspector as she had been requested to do. “It has occurred again,” she said.

“I see. Did you notice the time?”

“It was only a moment ago.”

“The same thing?”

“Yes,” she said, “the same. Surely you have some means of tracing—”

“Yes, Dame Lettie, we will get him, of course.”

A few moments later Dame Lettie telephoned to her brother Godfrey.

“Godfrey, it has happened again.”

“I’ll come and fetch you, Lettie,” he said. “You must spend the night with us.”

“Nonsense. There is no danger. It is merely a disturbance.”

“What did he say?”

“The same thing. And quite matter-of-fact, not really threatening. Of course the man’s mad. I don’t know what the police are thinking of, they must be sleeping. It’s been going on for six weeks now.”

“Just those words?”

“Just the same words—‘Remember you must die’—nothing more.”

“He must be a maniac,” said Godfrey.

Godfrey’s wife, Charmian, sat with her eyes closed, attempting to put her thoughts into alphabetical order which Godfrey had told her was better than no order at all, since she now had grasp of neither logic nor chronology. Charmian was eighty-five. The other day a journalist from a weekly paper had been to see her. Godfrey had subsequently read aloud to her the young man’s article:

…By the fire sat a frail old lady, a lady who once set the whole of the literary world (if not the Thames) on fire…. Despite her age, this legendary figure is still abundantly alive….

Charmian felt herself dropping off, and so she said to the maid, who was arranging the magazines on the long oak table by the window, “Taylor, I am dropping off to sleep for five minutes. Telephone to St. Mark’s and say I am coming.”

Just at that moment Godfrey entered the room holding his hat and wearing his outdoor coat. “What’s that you say?” he said.

“Oh, Godfrey, you made me start.”

“Taylor…” he repeated, “St. Mark’s…Don’t you realise there is no maid in this room, and furthermore, you are not in Venice.”

“Come and get warm by the fire,” she said, “and take your coat off” for she thought he had just come in from the street.

“I am about to go out,” he said. “I am going to fetch Lettie who is to stop with us to-night. She has been troubled by another of those anonymous calls.”

“That was a pleasant young man who called the other day,” said Charmian.

“Which young man?”

“From the paper. The one who wrote—”

“That was five years and two months ago,” said Godfrey.

“Why can’t one be kind to her?” he asked himself as he drove to Lettie’s house in Hampstead. “Why can’t one be more gentle?” He himself was eighty-seven, and in charge of all his faculties. Whenever he considered his own behaviour he thought of himself not as “I” but as “one.”

“One has one’s difficulties with Charmian,” he told himself.

“Nonsense,” said Lettie. “I have no enemies.”

“Think,” said Godfrey. “Think hard.”

“The red lights,” said Lettie. “And don’t talk to me as if I were Charmian.”

“Lettie, if you please, I do not need to be told how to drive. I observed the lights.” He had braked hard, and Dame Lettie was jerked forward.

She gave a meaningful sigh which, when the green lights came on, made him drive all the faster.

“You know, Godfrey,” she said, “you are wonderful for your age.”

“So everyone says.” His driving pace became moderate; her sigh of relief was inaudible, her patting herself on the back invisible.

“In your position,” he said, “you must have enemies.”

“Nonsense.”

“I say yes.” He accelerated.

“Well, perhaps you’re right.” He slowed down again, but Dame Lettie thought, I wish I hadn’t come.

They were at Knightsbridge. It was only a matter of keeping him happy till they reached Kensington Church Street and turned into V

icarage Gardens where Godfrey and Charmian lived.

“I have written to Eric,” she said, “about his book. Of course, he has something of his mother’s former brilliance, but it did seem to me that the subject-matter lacked the joy and hope which was the mark of a good novel in those days.”

“I couldn’t read the book,” said Godfrey. “I simply could not go on with it. A motor salesman in Leeds and his wife spending a night in a hotel with that communist librarian…Where does it all lead you?”

Eric was his son. Eric was fifty-six and had recently published his second novel.

“He’ll never do as well as Charmian did,” Godfrey said. “Try as he may.”

“Well, I can’t quite agree with that,” said Lettie, seeing that they had now pulled up in front of the house. “Eric has a hard streak of realism which Charmian never—”

Godfrey had got out and slammed the door. Dame Lettie sighed and followed him into the house, wishing she hadn’t come.

“Did you have a nice evening at the pictures, Taylor?” said Charmian.

“I am not Taylor,” said Dame Lettie, “and in any case, you always called Taylor Jean during her last twenty or so years in your service.”

Mrs. Anthony, their daily housekeeper, brought in the milky coffee and placed it on the breakfast table.

“Did you have a nice evening at the pictures, Taylor?” Charmian asked her.

“Yes, thanks, Mrs. Colston,” said the housekeeper.

“Mrs. Anthony is not Taylor,” said Lettie. “There is no one by name of Taylor here. And anyway you used to call her Jean latterly. It was only when you were a girl that you called Taylor Taylor. And, in any event, Mrs. Anthony is not Taylor.”

Godfrey came in. He kissed Charmian. She said, “Good morning, Eric.”

“He is not Eric,” said Dame Lettie.

Godfrey frowned at his sister. Her resemblance to himself irritated him. He opened The Times.

“Are there lots of obituaries to-day?” said Charmian.

“Oh, don’t be gruesome,” said Lettie.

“Would you like me to read you the obituaries, dear?” Godfrey said, turning the pages to find the place in defiance of his sister.

“Well, I should like the war news,” Charmian said.

“The war has been over since nineteen forty-five,” Dame Lettie said. “If indeed it is the last war you are referring to. Perhaps, however, you mean the First World War? The Crimean perhaps…?”

“Lettie, please,” said Godfrey. He noticed that Lettie’s hand was unsteady as she raised her cup, and the twitch on her large left cheek was pronounced. He thought in how much better form he himself was than his sister, though she was the younger, only seventy-nine.

Mrs. Anthony looked round the door. “Someone on the phone for Dame Lettie.”

“Oh, who is it?”

“Wouldn’t give a name.”

“Ask who it is, please.”

“Did ask. Wouldn’t give—”

“I’ll go,” said Godfrey.

Dame Lettie followed him to the telephone and overheard the male voice. “Tell Dame Lettie,” it said, “to remember she must die.”

“Who’s there?” said Godfrey. But the man had hung up.

“We must have been followed,” said Lettie. “I told no one I was coming over here last night.”

She telephoned to report the occurrence to the Assistant Inspector.

He said, “Sure you didn’t mention to anyone that you intended to stay at your brother’s home?”

“Of course I’m sure.”

“Your brother actually heard the voice? Heard it himself?”

“Yes, as I say, he took the call.”

She told Godfrey, “I’m glad you took the call. It corroborates my story. I have just realised that the police have been doubting it.”

“Doubting your word?”

“Well, I suppose they thought I might have imagined it. Now, perhaps, they will be more active.”

Charmian said, “The police…What are you saying about the police? Have we been robbed?”

“I am being molested,” said Dame Lettie.

Mrs. Anthony came in to clear the table.

“Ah, Taylor, how old are you?” said Charmian.

“Sixty-nine, Mrs. Colston,” said Mrs. Anthony.

“When will you be seventy?”

“Twenty-eighth November.”

“That will be splendid, Taylor. You will then be one of us,” said Charmian.

Chapter Two

There were twelve occupants of the Maud Long Medical Ward (aged people, female). The ward sister called them the Baker’s Dozen, not knowing that this is thirteen, but having only heard the phrase; and thus it is that a good many old sayings lose their force.

First came a Mrs. Emeline Roberts, seventy-six, who had been a cashier at the Odeon in the days when it was the Odeon. Next came Miss or Mrs. Lydia Reewes-Duncan, seventy-eight, whose past career was uncertain, but who was visited fortnightly by a middle-aged niece, very bossy towards the doctors and staff, very uppish. After that came Miss Jean Taylor, eighty-two, who had been a companion-maid to the famous authoress Charmian Piper after her marriage into the Colston Brewery family. Next again lay Miss Jessie Barnacle who had no birth certificate but was put down as eighty-one, and who for forty-eight years had been a newsvendor at Holborn Circus. There was also a Madame Trotsky, a Mrs. Fanny Green, a Miss Doreen Valvona, and five others, all of known and various careers, and of ages ranging from seventy to ninety-three. These twelve old women were known variously as Granny Roberts, Granny Duncan, Granny Taylor, Grannies Barnacle, Trotsky, Green, Valvona, and so on.

Sometimes, on first being received into her bed, the patient would be shocked and feel rather let down by being called Granny. Miss or Mrs. Reewes-Duncan threatened for a whole week to report anyone who called her Granny Duncan. She threatened to cut them out of her will and to write to her M.P. The nurses provided writing-paper and a pencil at her urgent request. However, she changed her mind about informing her M.P. when they promised not to call her Granny any more. “But,” she said, “you shall never go back into my will.”

“In the name of God that’s real awful of you,” said the ward sister as she bustled about. “I thought you was going to leave us all a packet.”

“Not now,” said Granny Duncan. “Not now, I won’t. You don’t catch me for a fool.”

Tough Granny Barnacle, she who had sold the evening paper for forty-eight years at Holborn Circus, and who always said, “Actions speak louder than words,” would send out to Woolworth’s for a will-form about once a week; this would occupy her for two or three days. She would ask the nurse how to spell words like “hundred” and “ermine.”

“Goin’ to leave me a hundred quid, Granny?” said the nurse. “Goin’ to leave me your ermine cape?”

The doctor on his rounds would say, “Well, Granny Barnacle, am I to be remembered or not?”

“You’re down for a thousand, Doc.”

“My word, I must stick in with you, Granny. I’ll bet you’ve got a long stocking, my girl.”

Miss Jean Taylor mused upon her condition and upon old age in general. Why do some people lose their memories, some their hearing? Why do some talk of their youth and others of their wills? She thought of Dame Lettie Colston who had all her senses intact, and yet played a real will-game, attempting to keep the two nephews in suspense, enemies of each other. And Charmian…Poor Charmian, since her stroke. How muddled she was about most things, and yet perfectly sensible when she discussed the books she had written. Quite clear on just that one thing, the subject of her books.

A year ago, when Miss Taylor had been admitted to the ward, she had suffered misery when addressed as Granny Taylor, and she thought she would rather die in a ditch than be kept alive under such conditions. But she was a woman practised in restraint; she never displayed her resentment. The lacerating familiarity of the nurses’ treatment merged in with her arthritis, and she bore t

hem both as long as she could without complaint. Then she was forced to cry out with pain during a long haunted night when the dim ward lamp made the beds into grey-white lumps like terrible bundles of laundry which muttered and snored occasionally. A nurse brought her an injection.

“You’ll be better now, Granny Taylor.”

“Thank you, nurse.”

“Turn over, Granny, that’s a good girl.”

“Very well, nurse.”

The arthritic pain subsided, leaving the pain of desolate humiliation, so that she wished rather to endure the physical nagging again.

After the first year she resolved to make her suffering a voluntary affair. If this is God’s will then it is mine. She gained from this state of mind a decided and visible dignity, at the same time as she lost her stoical resistance to pain. She complained more, called often for the bed pan, and did not hesitate, on one occasion when the nurse was dilatory, to wet the bed as the other grannies did so frequently.

Miss Taylor spent much time considering her position. The doctor’s “Well, how’s Granny Taylor this morning? Have you been making your last will and test—” would falter when he saw her eyes, the intelligence. She could not help hating these visits, and the nurses giving her a hair-do, telling her she looked like sixteen, but she volunteered mentally for them, as it were, regarding them as the Will of God. She reflected that everything could be worse, and was sorry for the youngest generation now being born into the world, who in their old age, whether of good family or no, educated or no, would be forced by law into Chronic Wards; she dared say every citizen in the Kingdom would take it for granted; and the time would surely come for everyone to be a government granny or grandpa, unless they were mercifully laid to rest in their prime.