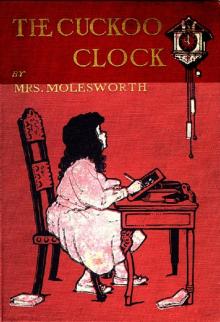

The Cuckoo Clock

Mrs. Molesworth

THE CUCKOO CLOCK

by

MRS. MOLESWORTH

Author of "Herr Baby," "Carrots," "Grandmother Dear," etc.

Illustrated by Walter Crane

London:MacMillan and Co.,and New York.

1895

IT WAS A LITTLE BOAT.]

TO

MARY JOSEPHINE,

AND TO THE DEAR MEMORY OF HER BROTHER,

THOMAS GRINDAL,

BOTH FRIENDLY LITTLE CRITICS OFMY CHILDREN'S STORIES.

Edinburgh, 1877.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. THE OLD HOUSE

II. _IM_PATIENT GRISELDA

III. OBEYING ORDERS

IV. THE COUNTRY OF THE NODDING MANDARINS

V. PICTURES

VI. RUBBED THE WRONG WAY

VII. BUTTERFLY-LAND

VIII. MASTER PHIL

IX. UP AND DOWN THE CHIMNEY

X. THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOON

XI. "CUCKOO, CUCKOO, GOOD-BYE!"

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

"WHY WON'T YOU SPEAK TO ME?"

MANDARINS NODDING

"MY AUNTS MUST HAVE COME BACK!"

SHE LOOKED LIKE A FAIRY QUEEN

"WHERE ARE THAT CUCKOO?"

"TIRED! HOW COULD I BE TIRED, CUCKOO?"

IT WAS A LITTLE BOAT

CHAPTER I.

THE OLD HOUSE.

"Somewhat back from the village street Stands the old-fashioned country seat."

Once upon a time in an old town, in an old street, there stood a veryold house. Such a house as you could hardly find nowadays, however yousearched, for it belonged to a gone-by time--a time now quite passedaway.

It stood in a street, but yet it was not like a town house, for thoughthe front opened right on to the pavement, the back windows looked outupon a beautiful, quaintly terraced garden, with old trees growing sothick and close together that in summer it was like living on the edgeof a forest to be near them; and even in winter the web of theirinterlaced branches hid all clear view behind.

There was a colony of rooks in this old garden. Year after year theyheld their parliaments and cawed and chattered and fussed; year afteryear they built their nests and hatched their eggs; year after year, I_suppose_, the old ones gradually died off and the young ones took theirplace, though, but for knowing this _must_ be so, no one would havesuspected it, for to all appearance the rooks were always the same--everand always the same.

Time indeed seemed to stand still in and all about the old house, as ifit and the people who inhabited it had got _so_ old that they could notget any older, and had outlived the possibility of change.

But one day at last there did come a change. Late in the dusk of anautumn afternoon a carriage drove up to the door of the old house, camerattling over the stones with a sudden noisy clatter that sounded quiteimpertinent, startling the rooks just as they were composing themselvesto rest, and setting them all wondering what could be the matter.

A little girl was the matter! A little girl in a grey merino frock andgrey beaver bonnet, grey tippet and grey gloves--all grey together, evento her eyes, all except her round rosy face and bright brown hair. Hername even was rather grey, for it was Griselda.

A gentleman lifted her out of the carriage and disappeared with her intothe house, and later that same evening the gentleman came out of thehouse and got into the carriage which had come back for him again, anddrove away. That was all that the rooks saw of the change that had cometo the old house. Shall we go inside to see more?

Up the shallow, wide, old-fashioned staircase, past the wainscotedwalls, dark and shining like a mirror, down a long narrow passage withmany doors, which but for their gleaming brass handles one would nothave known were there, the oldest of the three old servants led littleGriselda, so tired and sleepy that her supper had been left almostuntasted, to the room prepared for her. It was a queer room, foreverything in the house was queer; but in the dancing light of the fireburning brightly in the tiled grate, it looked cheerful enough.

"I am glad there's a fire," said the child. "Will it keep alight tillthe morning, do you think?"

The old servant shook her head.

"'Twould not be safe to leave it so that it would burn till morning,"she said. "When you are in bed and asleep, little missie, you won't wantthe fire. Bed's the warmest place."

"It isn't for that I want it," said Griselda; "it's for the light I likeit. This house all looks so dark to me, and yet there seem to be lightshidden in the walls too, they shine so."

The old servant smiled.

"It will all seem strange to you, no doubt," she said; "but you'll getto like it, missie. 'Tis a _good_ old house, and those that know bestlove it well."

"Whom do you mean?" said Griselda. "Do you mean my great-aunts?"

"Ah, yes, and others beside," replied the old woman. "The rooks love itwell, and others beside. Did you ever hear tell of the 'good people,'missie, over the sea where you come from?"

"Fairies, do you mean?" cried Griselda, her eyes sparkling. "Of courseI've _heard_ of them, but I never saw any. Did you ever?"

"I couldn't say," answered the old woman.

"My mind is not young like yours, missie, and there are times whenstrange memories come back to me as of sights and sounds in a dream. Iam too old to see and hear as I once could. We are all old here, missie.'Twas time something young came to the old house again."

"How strange and queer everything seems!" thought Griselda, as she gotinto bed. "I don't feel as if I belonged to it a bit. And they are all_so_ old; perhaps they won't like having a child among them?"

The very same thought that had occurred to the rooks! They could notdecide as to the fors and againsts at all, so they settled to put it tothe vote the next morning, and in the meantime they and Griselda allwent to sleep.

I never heard if _they_ slept well that night; after such unusualexcitement it was hardly to be expected they would. But Griselda, beinga little girl and not a rook, was so tired that two minutes after shehad tucked herself up in bed she was quite sound asleep, and did notwake for several hours.

"I wonder what it will all look like in the morning," was her lastwaking thought. "If it was summer now, or spring, I shouldn'tmind--there would always be something nice to do then."

As sometimes happens, when she woke again, very early in the morning,long before it was light, her thoughts went straight on with the samesubject.

"If it was summer now, or spring," she repeated to herself, just as ifshe had not been asleep at all--like the man who fell into a trance fora hundred years just as he was saying "it is bitt--" and when he woke upagain finished the sentence as if nothing had happened--"erly cold." "Ifonly it was spring," thought Griselda.

Just as she had got so far in her thoughts, she gave a great start. Whatwas it she heard? Could her wish have come true? Was this fairylandindeed that she had got to, where one only needs to _wish_, for it to_be_? She rubbed her eyes, but it was too dark to see; _that_ was notvery fairyland-like, but her ears she felt certain had not deceived her:she was quite, quite sure that she had heard the cuckoo!

She listened with all her might, but she did not hear it again. Couldit, after all, have been fancy? She grew sleepy at last, and was justdropping off when--yes, there it was again, as clear and distinct aspossible--"Cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo!" three, four, _five_ times, thenperfect silence as before.

"What a funny cuckoo," said Griselda to herself. "I could almost fancyit was in the house. I wonder if my great-aunts have a tame cuckoo in acage? I don't _think_ I ever heard of such a thing, but this is such aqueer house; everything seems different in it--perhaps they have a tamecuckoo. I'll ask them in the morning. It's very nice to hear, what

everit is."

And, with a pleasant feeling of companionship, a sense that she was notthe only living creature awake in this dark world, Griselda laylistening, contentedly enough, for the sweet, fresh notes of thecuckoo's friendly greeting. But before it sounded again through thesilent house she was once more fast asleep. And this time she slept tilldaylight had found its way into all but the _very_ darkest nooks andcrannies of the ancient dwelling.

She dressed herself carefully, for she had been warned that her auntsloved neatness and precision; she fastened each button of her greyfrock, and tied down her hair as smooth as such a brown tangle _could_be tied down; and, absorbed with these weighty cares, she forgot allabout the cuckoo for the time. It was not till she was sitting atbreakfast with her aunts that she remembered it, or rather was remindedof it, by some little remark that was made about the friendly robins onthe terrace walk outside.

"Oh, aunt," she exclaimed, stopping short half-way the journey to hermouth of a spoonful of bread and milk, "have you got a cuckoo in acage?"

"A cuckoo in a cage," repeated her elder aunt, Miss Grizzel; "what isthe child talking about?"

"In a cage!" echoed Miss Tabitha, "a cuckoo in a cage!"

"There is a cuckoo somewhere in the house," said Griselda; "I heard itin the night. It couldn't have been out-of-doors, could it? It would betoo cold."

The aunts looked at each other with a little smile. "So like hergrandmother," they whispered. Then said Miss Grizzel--

"We have a cuckoo, my dear, though it isn't in a cage, and it isn'texactly the sort of cuckoo you are thinking of. It lives in a clock."

"In a clock," repeated Miss Tabitha, as if to confirm her sister'sstatement.

"In a clock!" exclaimed Griselda, opening her grey eyes very wide.

It sounded something like the three bears, all speaking one after theother, only Griselda's voice was not like Tiny's; it was the loudest ofthe three.

"In a clock!" she exclaimed; "but it can't be alive, then?"

"Why not?" said Miss Grizzel.

"I don't know," replied Griselda, looking puzzled.

"I knew a little girl once," pursued Miss Grizzel, "who was quite ofopinion the cuckoo _was_ alive, and nothing would have persuaded her itwas not. Finish your breakfast, my dear, and then if you like you shallcome with me and see the cuckoo for yourself."

"Thank you, Aunt Grizzel," said Griselda, going on with her bread andmilk.

"Yes," said Miss Tabitha, "you shall see the cuckoo for yourself."

"Thank you, Aunt Tabitha," said Griselda. It was rather a bother to havealways to say "thank you," or "no, thank you," twice, but Griseldathought it was polite to do so, as Aunt Tabitha always repeatedeverything that Aunt Grizzel said. It wouldn't have mattered so much ifAunt Tabitha had said it _at once_ after Miss Grizzel, but as shegenerally made a little pause between, it was sometimes rather awkward.But of course it was better to say "thank you" or "no, thank you" twiceover than to hurt Aunt Tabitha's feelings.

After breakfast Aunt Grizzel was as good as her word. She took Griseldathrough several of the rooms in the house, pointing out all thecuriosities, and telling all the histories of the rooms and theircontents; and Griselda liked to listen, only in every room they cameto, she wondered _when_ they would get to the room where lived thecuckoo.

Aunt Tabitha did not come with them, for she was rather rheumatic. Onthe whole, Griselda was not sorry. It would have taken such a _very_long time, you see, to have had all the histories twice over, andpossibly, if Griselda had got tired, she might have forgotten about the"thank you's" or "no, thank you's" twice over.

The old house looked quite as queer and quaint by daylight as it hadseemed the evening before; almost more so indeed, for the view from thewindows added to the sweet, odd "old-fashionedness" of everything.

"We have beautiful roses in summer," observed Miss Grizzel, catchingsight of the direction in which the child's eyes were wandering.

"I wish it was summer. I do love summer," said Griselda. "But there is avery rosy scent in the rooms even now, Aunt Grizzel, though it iswinter, or nearly winter."

Miss Grizzel looked pleased.

"My pot-pourri," she explained.

They were just then standing in what she called the "great saloon," ahandsome old room, furnished with gold-and-white chairs, that must oncehave been brilliant, and faded yellow damask hangings. A feeling of awehad crept over Griselda as they entered this ancient drawing-room. Whatgrand parties there must have been in it long ago! But as for dancing init _now_--dancing, or laughing, or chattering--such a thing was quiteimpossible to imagine!

Miss Grizzel crossed the room to where stood in one corner a marvellousChinese cabinet, all black and gold and carving. It was made in theshape of a temple, or a palace--Griselda was not sure which. Any way, itwas very delicious and wonderful. At the door stood, one on each side,two solemn mandarins; or, to speak more correctly, perhaps I shouldsay, a mandarin and his wife, for the right-hand figure was evidentlyintended to be a lady.

Miss Grizzel gently touched their heads. Forthwith, to Griselda'sastonishment, they began solemnly to nod.

"Oh, how do you make them do that, Aunt Grizzel?" she exclaimed.

"Never you mind, my dear; it wouldn't do for _you_ to try to make themnod. They wouldn't like it," replied Miss Grizzel mysteriously. "Respectto your elders, my dear, always remember that. The mandarins are _many_years older than you--older than I myself, in fact."

Griselda wondered, if this were so, how it was that Miss Grizzel tooksuch liberties with them herself, but she said nothing.

"Here is my last summer's pot-pourri," continued Miss Grizzel, touchinga great china jar on a little stand, close beside the cabinet. "You maysmell it, my dear."

Nothing loth, Griselda buried her round little nose in the fragrantleaves.

"It's lovely," she said. "May I smell it whenever I like, Aunt Grizzel?"

"We shall see," replied her aunt. "It isn't _every_ little girl, youknow, that we could trust to come into the great saloon alone."

"No," said Griselda meekly.

Miss Grizzel led the way to a door opposite to that by which they hadentered. She opened it and passed through, Griselda following, into asmall ante-room.

"It is on the stroke of ten," said Miss Grizzel, consulting her watch;"now, my dear, you shall make acquaintance with our cuckoo."

The cuckoo "that lived in a clock!" Griselda gazed round her eagerly.Where was the clock? She could see nothing in the least like one, onlyup on the wall in one corner was what looked like a miniature house, ofdark brown carved wood. It was not so _very_ like a house, but itcertainly had a roof--a roof with deep projecting eaves; and, lookingcloser, yes, it _was_ a clock, after all, only the figures, which hadonce been gilt, had grown dim with age, like everything else, and thehands at a little distance were hardly to be distinguished from theface.

Miss Grizzel stood perfectly still, looking up at the clock; Griseldabeside her, in breathless expectation. Presently there came a sort ofdistant rumbling. _Something_ was going to happen. Suddenly two littledoors above the clock face, which Griselda had not known were there,sprang open with a burst and out flew a cuckoo, flapped his wings, anduttered his pretty cry, "Cuckoo! cuckoo! cuckoo!" Miss Grizzel countedaloud, "Seven, eight, nine, ten." "Yes, he never makes a mistake," sheadded triumphantly. "All these long years I have never known him wrong.There are no such clocks made nowadays, I can assure you, my dear."

"But _is_ it a clock? Isn't he alive?" exclaimed Griselda. "He looked atme and nodded his head, before he flapped his wings and went in to hishouse again--he did indeed, aunt," she said earnestly; "just likesaying, 'How do you do?' to me."

Again Miss Grizzel smiled, the same odd yet pleased smile that Griseldahad seen on her face at breakfast. "Just what Sybilla used to say," shemurmured. "Well, my dear," she added aloud, "it is quite right he_should_ say, 'How do you do?' to you. It is the first time he has seen_you_, though many a year ago he knew your dear grandmother,

and yourfather, too, when he was a little boy. You will find him a good friend,and one that can teach you many lessons."

"What, Aunt Grizzel?" inquired Griselda, looking puzzled.

"Punctuality, for one thing, and faithful discharge of duty," repliedMiss Grizzel.

"May I come to see the cuckoo--to watch for him coming out, sometimes?"asked Griselda, who felt as if she could spend all day looking up at theclock, watching for her little friend's appearance.

"You will see him several times a day," said her aunt, "for it is inthis little room I intend you to prepare your tasks. It is nice andquiet, and nothing to disturb you, and close to the room where your AuntTabitha and I usually sit."

So saying, Miss Grizzel opened a second door in the little ante-room,and, to Griselda's surprise, at the foot of a short flight of stairsthrough another door, half open, she caught sight of her Aunt Tabitha,knitting quietly by the fire, in the room in which they had breakfasted.

"What a _very_ funny house it is, Aunt Grizzel," she said, as shefollowed her aunt down the steps. "Every room has so many doors, and youcome back to where you were just when you think you are ever so faroff. I shall never be able to find my way about."

"Oh yes, you will, my dear, very soon," said her aunt encouragingly.

"She is very kind," thought Griselda; "but I wish she wouldn't call mylessons tasks. It makes them sound so dreadfully hard. But, any way, I'mglad I'm to do them in the room where that dear cuckoo lives."