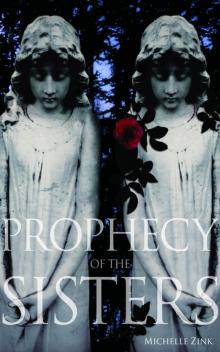

Prophecy of the Sisters

Michelle Zink

Copyright

Copyright © 2009 by Michelle Zink

Hand-lettering and interior ornamentation by Leah Palmer Preiss

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: August 2009

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-05334-1

Contents

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Acknowledgments

To my mother, Claudia Baker.

For betting on me.

1

Perhaps because it seems so appropriate, I don’t notice the rain. It falls in sheets, a blanket of silvery thread rushing to the hard almost-winter ground. Still, I stand without moving at the side of the coffin.

I am on Alice’s right. I am always on Alice’s right, and I often wonder if it was that way even in our mother’s womb, before we were pushed screaming into the world one right after the other. My brother, Henry, sits near Edmund, our driver, and Aunt Virginia, for sit is all Henry can do without the use of his legs. It was only with some effort that Henry and his chair were carried to the graveyard on the hill so that he could see our father laid to rest.

Aunt Virginia leans in to speak to us over the drumming rain. “Children, we must be going.”

The reverend has long since left. I cannot say how long we have been standing at the mound of dirt where my father’s body lay, for I have been under the shelter of James’s umbrella, a quiet world of protection providing the smallest of buffers between me and the truth.

Alice motions for us to leave. “Come, Lia, Henry. We’ll return when the sun is shining and lay fresh flowers on Father’s grave.” I was born first, though only by minutes, but it has always been clear that Alice is in charge.

Aunt Virginia nods to Edmund. He gathers Henry into his arms, turning to begin the walk back to the house. Henry’s gaze meets mine over Edmund’s shoulder. Henry is only ten, though far wiser than most boys of his age. I see the loss of Father in the dark circles under my brother’s eyes. A stab of pain finds its way through my numbness, settling somewhere over my heart. Alice may be in charge, but I am the one who has always felt responsible for Henry.

My feet will not move, will not take me away from my father, cold and dead in the ground. Alice looks back. Her eyes find mine through the rain.

“I’ll be along in a moment.” I have to shout to be heard, and she nods slowly, turning and continuing along the path toward Birchwood Manor.

James takes my gloved hand in his, and I feel a wave of relief as his strong fingers close over mine. He moves closer to be heard over the rain.

“I’ll stay with you as long as you want, Lia.”

I can only nod, watching the rain leak tears down Father’s gravestone as I read the words etched into the granite.

Thomas Edward Milthorpe

Beloved Father

June 23, 1846–November 1, 1890

There are no flowers. Despite my father’s wealth, it is difficult to find flowers so near to winter in our town in northern New York, and none of us have had the energy or will to send for them in time for the modest service. I am ashamed, suddenly, at this lack of forethought, and I glance around the family cemetery, looking for something, anything, that I might leave.

But there is nothing. Only a few small stones lying in the rain that pools on the dirt and grass. I bend down, reaching for a few of the dirt-covered stones, holding my palm open to the rain until the rocks are washed clean.

I am not surprised that James knows what I mean to do, though I don’t say it aloud. We have shared a lifetime of friendship and, recently, something much, much more. He moves forward with the umbrella, offering me shelter as I step toward the grave and open my hand, dropping the rocks along the base of Father’s headstone.

My sleeve pulls with the motion, revealing a sliver of the strange mark, the peculiar, jagged circle that bloomed on my wrist in the hours after Father’s death. I steal a glance at James to see if he has noticed. He hasn’t, and I pull my arm further inside my sleeve, lining the rocks up in a careful row. I push the mark from my mind. There is no room there for both grief and worry. And grief will not wait.

I stand back, looking at the stones. They are not as pretty or bright as the flowers I will bring in the spring, but they are all I have to give. I reach for James’s arm and turn to leave, relying on him to guide me home.

It is not the warmth of the parlor’s fire that keeps me downstairs long after the rest of the household retires. My room has a firebox, as do most of the rooms at Birchwood Manor. No, I sit in the darkened parlor, lit only by the glow of the dying fire, because I do not have the courage to make my way upstairs.

Though Father has been dead for three days, I have kept myself well occupied. It has been necessary to console Henry, and though Aunt Virginia would have made the arrangements for Father’s burial, it seemed only right that I should help take matters in hand. This is what I have been telling myself. But now, in the empty parlor with only the ticking mantel clock for company, I realize that I have been avoiding this moment when I shall have to make my way up the stairs and past Father’s empty chambers. This moment when I shall have to admit he is really gone.

I rise quickly, before I lose my nerve, focusing on putting one slippered foot in front of the other as I make my way up the winding staircase and down the hall of the East Wing. As I pass Alice’s room, and then Henry’s, my eyes are drawn to the door at the end of the hall. The room that was once my mother’s private chamber.

The Dark Room.

As little girls, Alice and I spoke of the room in whispers, though I cannot say how we came to call it the Dark Room. Perhaps it is because in the tall-ceilinged rooms where fires blaze nonstop nine months out of the year, it is only the un-inhabited rooms that are completely dark. Yet even when my mother was alive, the room seemed dark, for it was in this room that she retreated in the months before her death. It was in this room that she seemed to drift further and further away from us.

I continue to my room, where I undress and pull on a nightgown. I am sitting on the bed, brushing m

y hair to a shine, when a knock stops me midstroke.

“Yes?”

Alice’s voice finds me from the other side of the door. “It’s me. May I come in?”

“Of course.”

The door creaks open, and with it comes a burst of cooler air from the unheated hallway. Alice closes it quickly, crossing to the bed and sitting next to me as she did when we were children. Our nightdresses, like us, are nearly identical. Nearly but not quite. Alice’s are made with fine silk at her request while I prefer comfort over fashion and wear flannel in every season but summer.

She reaches out a hand for the brush. “Let me.”

I hand her the brush, trying not to show my surprise as I turn away to give her access to the back of my head. We are not the kind of sisters who engage in nightly hair brushing or confided secrets.

She moves the brush in long strokes, starting at the crown of my head and traveling all the way down to the ends. Watching our reflection in the looking glass atop the bureau, it is hard to believe anyone can tell us apart. From this distance and in the glow of the firelight, we look exactly the same. Our hair shimmers the same chestnut in the dim light. Our cheekbones angle at the same slant. I know, though, that it is the subtle differences that are unmistakable to those who know us at all. It is the slight fullness in my face that stands in contrast to the sharper contours of my sister’s and the somber introspection in my eyes that opposes the sly gleam in her own. It is Alice who shimmers like a jewel under the light, while I brood, think, and wonder.

The fire crackles in the firebox, and I close my eyes, allowing my shoulders to loosen as I fall into the soothing rhythm of the brush in my hair, Alice’s hand smoothing the top of my head as she goes.

“Do you remember her?”

My eyelids flutter open. It is an uncommon question, and for a moment, I’m unsure how to answer. We were only girls of six when our mother died in an inexplicable fall from the cliff near the lake. Henry had been born just a few months before. The doctors had already made it clear that my father’s long-desired son would never have the use of his legs. Aunt Virginia always said that Mother was never the same after Henry’s birth, and the questions surrounding her death still linger. We don’t speak of it or the inquiry that followed.

I can only offer her the truth. “Yes, but only a little. Do you?”

She hesitates before answering, the brush still moving. “I believe so. But only in flashes. Little moments, I suppose. I often wonder why I can remember her green dress, but not the way her voice sounded when she read aloud. Why I can clearly see the book of poems she kept on the table in the parlor but not remember the way she smelled.”

“It was jasmine and… oranges, I think.”

“Is that it? The way she smelled?” Her voice is a murmur behind me. “I didn’t know.”

“Here. My turn.” I twist around, reaching for the brush.

She turns as compliant as a child. “Lia?”

“Yes?”

“If you knew something, about Mother… If you remembered something, something important, would you tell me?” Her voice is quiet, more unsure than I’ve ever heard it.

My breath catches in my throat with the strange question. “Yes, of course, Alice. Would you?”

She hesitates, the only sound in the room the soft pull of the brush through silken hair. “I suppose so.”

I move the brush through her hair, remembering. Not my mother. Not now. But Alice. Us. The twins. I remember the time before Henry’s birth, before Mother took refuge alone in the Dark Room. The time before Alice became secretive and strange.

It would be easy to look back on our childhood and assume that Alice and I were close. In the fondness of memory, I recall her soft breath in the dark of night, her voice mumbling into the blackness of our shared nursery. I try to remember our proximity as comfort, to ignore the voice that reminds me of our differences even then. But it doesn’t work. If I am honest, I will admit we have always eyed each other warily. Still, it was once her soft hand I grasped before falling into sleep, her curls I brushed from my shoulder when she slept too close.

“Thank you, Lia.” Alice turns around, looking me in the eyes. “I miss you, you know.”

My cheeks are warm under the scrutiny of her stare, the closeness of her face to mine. I shrug. “I’m right here, Alice, as I’ve always been.”

She smiles, but in it is something sad and knowing. Leaning in, she wraps her thin arms around me as she did when we were children.

“And I as well, Lia. As I’ve always been.”

She stands, leaving without another word. I sit on the edge of the bed in the dim light of the lamp, trying to place her uncommon sadness. It is unlike Alice to be reflective, though with Father’s death I suppose we are all feeling vulnerable.

Thoughts of Alice allow me to avoid the moment when I will have to look at my wrist. I feel a coward as I try to find the courage to pull back the sleeve of my nightdress. To look again at the mark that appeared after Father’s body was found in the Dark Room.

When I finally pull back my sleeve, telling myself that whatever is there is there just the same, whether or not I look, I have to press my lips together to keep from crying out. It isn’t the mark on the soft underside of my wrist that is a surprise, but how much darker it is now than it was even this morning. How much clearer the circle, though I still cannot decipher the ridges that thicken it, making the edges seem uneven.

I fight a surge of rising panic. It seems there should be some recourse, something I should do, someone I should tell, but whom might I tell such a thing? Once, I would go to Alice, for whom else might I trust with such a secret? Even still, I cannot ignore the ever-growing distance between us. It has made me wary of my sister.

I tell myself the mark will go away, that there is no need to tell someone such a strange thing when surely it will be gone in a few days. Instinctively, I think this a lie but convince myself I have a right to believe it on a day such as this.

On the day I have buried my father.

2

The thin November light is spreading its fingers across the room when Ivy pads in carrying a kettle of hot water.

“Good morning, Miss.” She pours the water into the basin on the washstand. “Shall I help you dress?”

I lift myself up on my elbows. “No, thank you. I’ll be fine.”

“Very well.” She leaves the room, empty kettle in hand.

I throw back the covers and make my way to the washstand, swirling a hand in the basin to cool the water before I wash. When I am finished, I dry my cheeks and forehead, peering into the glass. My green eyes are bottomless, empty, and I wonder if it is possible to change from the inside out, if sadness can radiate outward, through the veins and organs and skin for all to see. I shake my head at the morbid notion, watching my auburn hair, unbound, brush my shoulders in the looking glass.

I take off my nightdress and pull a petticoat and stockings from the bureau, beginning to dress. I am smoothing the second stocking up my thigh when Alice sweeps in without knocking.

“Good morning.” She drops heavily onto the bed, looking up at me with the breathless charm that is uniquely Alice.

It surprises me still, her effortless swing from barely concealed bitterness to sorrow to carefree calm. It should not, for Alice’s moods have always been mercurial. But her face bears no trace of sadness, no trace of last night’s melancholy. In truth, other than her simple gown and lack of jewelry, she looks no different than she ever has. Perhaps I am the only one to change from the inside out after all.

“Good morning.” I hurry and fasten the stocking, feeling guilty that I’ve lazed in my room for so long when my sister is already up and about. I move to the cupboard, both to find a gown and to avoid the eyes that always seem to look too deeply into mine.

“You should see the house, Lia. The entire staff is in mourning clothes, on Aunt Virginia’s orders.”

I turn to look at her, noticing the flush on he

r cheeks and something like excitement in her eyes. I push down my annoyance. “Many households observe the mourning period, Alice. Everyone loved Father. I’m sure they don’t mind paying their respects.”

“Yes, well, now we shall be stuck inside for an interminable time, and it is so very dull here. Do you suppose Aunt Virginia will allow us to attend classes next week?” She continues without waiting for an answer. “Of course, you don’t even care! You would be perfectly happy to never see Wycliffe again.”

I do not bother arguing. It is well-known that Alice yearns for the more civilized life of the girls at Wycliffe, the school where we attend classes twice a week, while I always feel like an exotic animal under glass. I steal glimpses of her at school, glittering under the niceties of polite society, and imagine her like our mother. It must be true, for it is I who finds pleasure in the stillness of Father’s library and Alice alone who can conjure the gleam of our mother’s eyes.

We spend the day in the almost-silence of the crackling fire. We are accustomed to the isolation of Birchwood and have learned to occupy ourselves within its somber walls. It is like any other rainy day save for the lack of Father’s big voice booming from the library or the smell of his pipe. We don’t speak of him or his strange death.

I avoid looking at the clock, fearing the slow passing of time that will only seem slower if I watch its progress. It works, in a manner of speaking. The day passes more quickly than I expect, the small interruptions for lunch and dinner easing me toward the time when I can escape to the nothingness of sleep.

This time I don’t look at my wrist before climbing into bed. I don’t want to know if the mark is still there. If it has changed.

If it is deeper or darker. I slip into bed, sinking toward darkness without further thought.

I am in the in-between place, the place we drift through before the world falls away into sleep, when I hear the whispering. At first, it is only the call of my name, beckoning from some far-off place. But the whisper builds, becoming many voices, all murmuring frantically, so quickly that I can only make out an occasional word. It grows and grows, demanding my attention until I cannot ignore it a second longer. Until I sit straight up in bed, the last whispered words echoing through the caverns of my mind.