The Amulet

Michael McDowell

THE AMULET

by

MICHAEL McDOWELL

With a new introduction by

POPPY Z. BRITE

VALANCOURT BOOKS

The Amulet by Michael McDowell

First published as a paperback original by Avon Books in 1979

First Valancourt Books edition 2013

Copyright © 1979 by Michael McDowell

Introduction © 2013 by Poppy Z. Brite

Published by Valancourt Books, Richmond, Virginia

http://www.valancourtbooks.com

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher, constitutes an infringement of the copyright law.

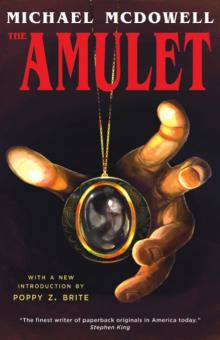

Cover by Eric Robertson

INTRODUCTION

In Michael McDowell’s work, the familiar horror fiction setup of a good situation going bad is almost always subverted: the situation starts off bad and gets much, much worse. Nowhere is this truer than in McDowell’s first published novel, The Amulet. Book blogger Will Errickson (“Too Much Horror Fiction”) accurately describes it as “an exquisitely drawn depiction of class and racial strife in small-town Southern life . . . and death. The first five or six chapters are told with little to no dialogue, just McDowell masterfully spinning a tapestry of the harsh realities of the unforgiving people and landscape of Pine Cone, Alabama.”

Tales of cursed objects are surely as old as the horror genre itself, but McDowell puts an unusual twist on this old trope by never providing, or even strongly suggesting, much of an explanation for the origin of the evil amulet we encounter in this story. The tale’s antagonist, a loathsome woman named Jo Howell, may have inherited or stolen it from the cousin who raised her, but it almost seems a pure physical manifestation of Jo’s anger, bitterness, and jealousy toward the town of Pine Cone, which she sees as having conspired to destroy her son. In reality, Dean Howell has been mutilated and rendered (probably) comatose by an exploding rifle while training to fight in Vietnam, but in Jo Howell’s world, there are no accidents; everything is a conspiracy against her, and every perceived slight requires a disproportionately deadly act of revenge. As McDowell told Douglas E. Winter in a 1985 interview, “Southerners are Gothic—there’s no other word for it. They’re warped in an interesting way.”1

1 Interview with Michael McDowell, Faces of Fear: Encounters with the Creators of Modern Horror, ed. Douglas E. Winter, Berkley Books, 1985.

While most of McDowell’s horror fiction is set in the American South—and depicts that setting with an unrivaled eye—it was written in self-imposed exile. McDowell grew up in southeastern Alabama near the Florida border, but after leaving to attend Harvard, he made New England his home for the rest of his life. He had planned to teach after graduation, but found that the work interfered with his writing: “I discovered that teaching used the same sort of energy as writing, so that I couldn’t do both seriously. So I made a decision—and the decision was a brave one for me—not to continue in the chosen profession, not to take the easy way out of teaching and finding a job in a junior college somewhere.”2 Instead he took a job as a secretary and wrote at night, producing six novels and a number of screenplays, none of which sold. Then, one night at the movies, he saw a trailer for The Omen and was inspired—not by the trailer itself, but by the idea that possessed children in horror stories always seem to have suitably evil monikers like Damien and Regan. “I thought, ‘Well, isn’t it convenient that these possessed children have such diabolical names? What if you had a possessed child called Fred?’ . . . And I went home and tried to work out a plot, and then started to write.”3

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

What resulted was The Amulet. Fred doesn’t figure significantly in the story, and there are no possessed children to be found. What ended up captivating McDowell was the potential for gory, creative murder. “Before I started [The Amulet], I knew that I was going to have a sequence of deaths, and that the amulet would pass from one to the other. Beyond that, I didn’t know what I was going to do, so a friend and I sat down one evening and thought: ‘How can you kill people with things from around the house?’ We came up with an icepick in the ear, and throwing a baby into a washing machine, and decapitation by a ceiling fan, and so on. So I wrote those down and then I figured out ways to connect them.”

If most writers simply wrote death scenes and then “figured out ways to connect them,” the results would be disastrous. McDowell’s characteristic black humor elevates the scenes, keeps the deaths from becoming repetitive, and eventually ends up driving the story: without it, the novel would surely have bogged down in unrelenting bleakness. McDowell is at his cleverest in dialogue, not least because his ear for rural Alabama speech is letter-perfect:

“We gone get in trouble, Sheriff?” the farmer asked. “You know,” he said piteously, “I didn’t mean to run the woman down.”

“Well,” Garrett replied, “wasn’t your fault, like you said. She wasn’t wearing white, and she ought not to be running up on bridges when the sun’s gone down. And she ought not be killing her husband with pine branches either.”

“Ought not do that in any case,” added the deputy. “No, sir,” he added a moment later, for emphasis, when no one thought to second his opinion.

In fact, McDowell felt so comfortable with the dialogue of his characters that he first wrote The Amulet as a hundred-page screenplay, then “novelized” it. Avon Books bought the novel, asked for an expansion of the then-200-page manuscript, and published it as a paperback original in 1979. McDowell was able to quit his secretarial job and write full-time. He also earned a Ph.D. from Brandeis that year, writing his dissertation on attitudes toward death in America between 1825 and 1865. Over the next several years he published an astonishing variety of novels under his own name as well as several pseudonyms. The Amulet and McDowell’s other horror novels largely concern themselves with twisted family relationships. “I have no interest in having a family for myself,” he told Douglas E. Winter. “There have to be families out there—I just don’t want to have anything to do with them. I think they’re violent and I think they’re oppressive and I think they’re manipulative—and I think they’re interesting because of all those things.”4

4 Ibid.

It’s difficult not to wonder how deeply McDowell’s view of families was influenced by growing up gay in the rural South of the 1950s and 1960s. Outside of the extensive Faces of Fear interview and a Wikipedia entry, little biographical information is readily available, but we know that McDowell was a member of the National Gay Task Force, spent thirty years with his partner Laurence Senelick, and was one of the first modern horror authors to write about gay characters who didn’t live tragically or die horribly (or, at least, were no likelier to do so than their heterosexual counterparts). There’s little queerness to be found in The Amulet, and the later characters’ sexuality is more implied than stated5—for instance, James Caskey of the Blackwater books is a fey man who collects china and “had no business being married in the first place. He had the heart and the mind of the perennial bachelor, and the acquisition of a wife had done nothing to erase the stamp of femininity with which he was so firmly branded”6—but in the conservative world of 1980s paperback horror, even this was risky stuff, and may have been the reason McDowell’s work never achieved wider popularity in his lifetime despite praise from authors like Stephen King, who called him “the finest writer of paperback originals in America today” and recommended several of McDowell’s novels in the appendix to his seminal overview of the modern horror genre, Danse Macabre.

5 I am dealing here with

the novels McDowell published under his own name. Some of his pseudonymous works, particularly the novels by “Nathan Aldyne,” do contain openly gay characters.

6 Blackwater: The Flood, Avon Books, 1983.

Sadly, McDowell’s books have been out of print since well before his death in 1999, and today he is probably best known for writing the screenplay of the movie Beetlejuice—a worthy achievement, but (in this writer’s opinion) not a patch on his prose work. The volume you now hold in your hands is an attempt to change that. If you enjoy it—and I feel pretty certain you will—then it is well worth your time to seek out his other work, particularly Blackwater, a wonderfully Southern Gothic family saga in which some family members periodically transform into rapacious Lovecraftian fish-frog creatures, and The Elementals, surely one of the most terrifying novels ever written. “If I like an author,” he said, “I want him to have forty books so that I can read every one of them. And that’s how I see myself—as someone who writes constantly, and who writes lots and lots so that people who like me can have lots and lots to read. It seems to me that that’s a simple pleasure and one I like to fulfill.”7

7 Faces of Fear.

The simple pleasure of things starting out terrible . . . and getting much, much worse.

Poppy Z. Brite

New Orleans

May 2013

Poppy Z. Brite is the author of eight novels, including Lost Souls, Exquisite Corpse, and Liquor, as well as several short story collections and nonfiction works. Brite now goes by the name Billy Martin and lives in New Orleans with his partner, the photographer and artist Grey Cross.

THE AMULET

TO DAVID AND JANE

Had I but all of them, thee and thy treasures,

What a wild crowd of invisible pleasures!

To carry pure death in an earring, a casket,

A signet, a fan-mount, a fillagree-basket!

Robert Browning

“The Laboratory”

PROLOGUE

In March 1965, Fort Rucca—in the southeastern corner of the state of Alabama—was a busy, crowded area. Here new army recruits underwent basic training, and were further instructed in helicopter piloting and helicopter maintenance. It had become known what a terrible war was being fought in the jungles of Vietnam, and how little prepared our soldiers were against that tropical foliage, where thousands of men, and whole factories of machinery and weapons could be moved along supply trails that were invisible from the air. The earliest veterans of the war had come back, and were frantically training more men, with the terrain of Vietnam in mind. The Chattahoochee River is not far from Fort Rucca, and the basin of that slow-moving, wide stream is very similar in density and quality of vegetation, and was the ideal proving ground for those men who would soon see combat.

Fort Rucca is located in the most unfriendly section of Alabama, a flat, featureless landscape, that seems always hot, always menacing, always indignant when farmers try to scratch their meager livings out of the hard soil. The vegetation is coarse, and sharp, and not much good for anything. The only plants that seem to grow well are trees whose lumber is worthless, and shrubs with thorns and briars. The four kinds of poisonous snakes indigenous to the continental United States are found together in only one place: the Wiregrass area of Alabama. That seems only natural to the people who live there.

In one corner of the crowded camp, “wiregrass,” the coarse ground cover that gives the area its nickname, had been shorn close, and an extensive firing range constructed for the rifle instruction and practice of army inductees from all over the country. One very hot Friday morning, shortly before noon, and underneath a blazing, cloudless sky, about seventy-five men, in three equal groups, were shooting at targets cut in the shape of men, with yellow faces and slanted eye-slits.

Well behind the line of prone, firing privates were the other fifty who were waiting their turn. Two men, not much different from the others, leaned against the wire fence that separated the camp from the dusty peanut fields belonging to an Alabama state senator. The senator had made a fortune out of this soil, obtaining government subsidies for not raising cotton and corn, and taking a tax loss on his income each year, because somehow or other, the peanut crop always failed. He was one of the very few who could make money off the land of the wiregrass.

The two privates could not have cared less about the senator’s peanut fields. One of the men was of middle height, coarsely handsome, and in extraordinary health; from his thick accent it was apparent that he was very much at home in this part of the country. His companion was somewhat taller, but more delicate; his features had a distinctly Jewish cast to them.

The first man, whose name was Dean Howell, said to his companion, “You look here at this, Si.” Dean held up the rifle he carried, and thrust the butt of it before Simon’s eyes. “You see that pinecone?”

Si nodded. He had already noticed the small pinecone embossed in the lowest corner of the butt of every rifle on the firing range.

Dean continued: “This rifle was made—start to finish—in Pine Cone, Alabama, and my wife Sarah is right there on that ’ssembly line. She had her hands on this piece ’fore I did. It’s like it was blessed, in a way.”

Si nodded. “How far is Pine Cone from here?”

“Oh,” said Dean, “if you was to stand on my shoulders, you could see it. It’s about thirty miles.” He pointed vaguely over the senator’s peanut fields. “We got pine trees and cotton fields and the Pine Cone Munitions Factory and that’s about all.” He waited a moment, while the line of men fired at the targets again, and then continued, “But the pine trees get burned down, and the cotton gets eaten up, and so there’s the rifle plant that’s left. Ever’body I know works in that place. You know why?”

Si shook his head, and asked, “Why?”

Dean Howell spoke harshly now. “I tell you why.” The rifles fired once more.

“Why?” Si repeated his question. Dean Howell was being deliberately mysterious.

Dean’s strange smile turned sour. “ ’Cause,” he said, with unexpected bitterness, “you get a job there, and you get a deferment—‘Services necessary to the National Welfare and Security.’ Ever’body I know works in that place,” he repeated, with angered significance.

“And you wanted a job there too?” said Si, who had begun to understand Dean’s apparent disgust with the Pine Cone Munitions Factory.

“You’re right, you’re exactly right,” said Dean, “and I ought to be there right now myself. I ought to have a good job there, inside, not out in the sun like this, building these damn things, or carrying ’em from one place to another. Not firing ’em off. I ought to be there, ’cause I know the man who’s in charge of hiring there, I know him real good, ’cause we used to go after the quail together ever’ year.”

“Why didn’t he hire you then?”

“Well, he said he didn’t have no place for me, and that he just had to wait until something opened up, but goddamn I’d have taken anything, I tell you, not to have to go to goddamn Asia. I love this country, but goddamn, I want to have both my legs this time come three years. Well, he was ‘waiting for something to open up’ when I got drafted, and here I am.”

“But your wife had a job there, you said.”

“Yeah,” said Dean Howell, “Larry thought he could make ever’thing all right by putting Sarah on the line. That’s what they call the ’ssembly line in Pine Cone—the ‘line’ and ever’body knows what you’re talking about. But Sarah being on the line didn’t make nothing all right. Sarah and I hadn’t been married more than a year when I got drafted. Even the people down at the draft board said it was a shame I was getting taken away like that, but they said there wasn’t nothing they could do about it, either.”

“Dean,” said Si, “it sounds like you got the wrong end of the stick.”

“Listen, Si, you listen to me—we both did.” The two men shook their heads, for neither of them was happy to be in Fort Rucca, with onl

y the prospect of jungle combat before them. There were many rumors just then going around the camp, about tortures that the Vietnamese had designed just to prolong the deaths of captured American soldiers, of the terrible things they could do to a man that would make him beg for immediate execution. Dean pulled a handkerchief out of his back pocket and wiped his forehead and his hands of the sweat there, and then handed it to Si, who did the same. They were being called forward by the platoon sergeant to take their places on the firing line.

They moved quickly through the crowd of shifting men, and dropped to the ground beside one another. Once again, Dean silently pointed out to Si the pinecone on the butt of the rifle, smiled, and winked; he evidently considered the pinecone insignia a kind of good luck charm.

At the other end of the range, the spent targets had been replaced with fresh ones, and the sergeant took his place at the end of the row of prone, expectant men. “Ready!” he called out. “Aim! Fire!”

Briefly the noise was deafening to Si, but the sound continued longer than was usual; then he realized it was not a firing rifle, but a man screaming that he heard. Si turned instinctively to his friend.

Dean Howell was struggling slowly to his feet, both hands clapped over his face. Blood spurted out between his fingers, and poured down over his sweat-stained khaki fatigues. He reeled with the injury, and still screaming, fell back into the stiff brown grass. The Pine Cone rifle lay blown in pieces beneath his writhing body.

Si moved closer, and pulled Dean’s hands away from his face, to try to quiet him and determine the extent of the injury. But when he saw the corrugated, bloody mess that was hardly recognizable as a face, with one of the eyeballs dangling by the distended optic nerve, Si staggered backward with unconquerable disgust, and Dean continued his inarticulate screams until he gagged on his own blood.